Death, Starvation, New Terror Recruits … Aftermath Of Borno’s IDP Resettlement

The government insists it is resettling the displaced people for their good, but so far it hasn’t seemed that way. For many of the returnees, almost everything that could go wrong has.

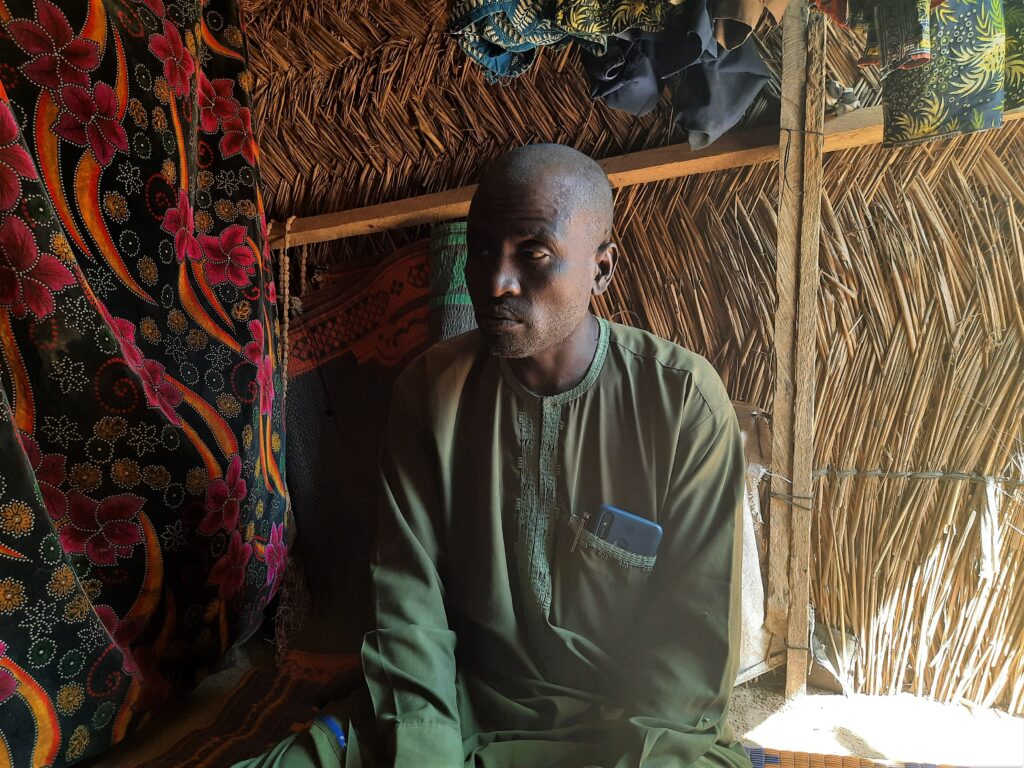

When Gambo Muhammad, 72, left his hometown of Sidiya Kari in Kala Balge, Northeast Nigeria, he felt he had no other choice. Rampaging terrorists were hunting them ‘like rabbits,’ he recalls, especially men like him. Six years later, after finally settling in a camp for Internally Displaced People (IDPs) in the state capital, Maiduguri, he would again have to leave. He would again feel he had no choice. This time, it would not exactly be the terrorists’ fault.

Borno State, the heart of the Boko Haram insurgency, notably hosts about half of the approximately 3.2 million displaced people across Nigeria. Over 305,000 of the IDPs are crammed in the Maiduguri metropolis, which has recently been the safest part of the war-torn state. The crisis has attracted interest from all over the world and humanitarian workers swarm the town. But there’s something about this arrangement that political leaders find uncomfortable.

The urge to shut down displacement camps in Borno is not new. Former state governor Kashim Shettima had said in 2016 that, by the following year, all the camps would be closed. But this plan was later put on hold due to lingering insecurity.

Less than a year after he took over as governor, Babagana Zulum keyed into the same gospel, encouraging the prioritisation of resettlement houses over IDP camps. At first, the deadline for the closure of camps within Maiduguri was set as May 2021, then it was moved to December. Some of the government-run camps have indeed been closed, with many of the occupants resettled. A few others remain open, but it is uncertain how long this will remain so.

There have been concerns from international aid and advocacy organisations such as Amnesty International, the Red Cross, and Human Rights Watch. But the authorities persist, citing various reasons for their devotion to resettlement: the prevalence of early child marriage, prostitution, drug abuse, and thuggery at the camps; loss of dignity; growing aid dependency and ‘entitlement complex’ among IDPs; the need to build resilience; and the return of ‘relative peace’ to various communities.

At a time of endless hostilities, resettlement is seen as the closest thing to life before the insurgency. The government has often promised the resettlers and returnees safety, support, and sources of income. But the programme’s implementation is far from perfect.

According to Gambo, Zulum visited Farm Centre (Gidan Taki) IDP camp one Friday in 2021 and announced after the Jum’at prayer that the government no longer wanted people staying at the place. He says they were given ₦30,000 to convey their properties to the Shuwari resettlement site in neighbouring Jere Local Government Area (LGA). Buildings had been constructed but they were not enough. Others had to set up tents using recycled tarpaulin and wood, giving the environment the semblance of a typical displacement camp.

Hunger, hunger everywhere

“At Gidan Taki [camp], we got food, even if it was small, from time to time. But, since we came here, who has given us food? He [the governor] promised he would give us food but we still have not seen anything. We haven’t seen the man himself, much less food,” says Gambo. “Hunger remains our biggest problem. We sleep without food. Sometimes, we spend up to two days without eating.”

Often grappling with the loss of livelihoods and lack of adequate humanitarian assistance, many IDPs in Northeast Nigeria have gotten used to not having enough to eat. But those in some resettled communities are having it much worse.

This is because many IDPs in the state capital still receive support from aid organisations and members of the host community. They are hired to work on farms and paid daily wages. They engage in other manual labour. Those who run businesses such as tailoring and cap-knitting have access to a broader clientele rich enough to patronise them. In the resettled communities, however, these opportunities are absent.

The government imagines that returnees would roll their sleeves, get to work on allotted farms, and become financially independent. But this is not practical in many places due to the risk of getting killed or abducted. There’s also the fact that farmlands are just not available — especially since those resettled are merely taken to other garrison towns in their LGAs, not their original rural communities which are still unsafe. Much like in Maiduguri, they are still strangers. “We can’t get farmlands because this isn’t our home,” explains Gidew Kamsulum, 37. “We are not indigenes.”

Sixty-something-year-old Gujja Ibrahim manages to be cheerful despite her troubles and even laughs as she talks about her experience with increasing hunger. It’s perhaps her way of staying strong mentally for the ambitious task of staying alive. Gujja was one of the IDPs moved to the Shuwari site last August.

At Gidan Taki, she had a small okra farm. After the crop’s season, she offered her services to other farm owners who either paid cash or rewarded her with grains. She was not making much but at least she was independent. And even though she was not registered at the camp, officials of the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) still gave her some rice and maize during distribution exercises. All that has changed since the resettlement.

The afternoon in late January when HumAngle met her, Gujja had just returned from the forest where she had gone to get firewood. It’s a daily ritual, she says; “If I am sick, people will take care of me, but now I have to go and work. This is the situation we’re in now.” She understands she has to be careful not to rely too much on other returnees since they themselves are having it rough.

Because of her old age, she is unable to travel far distances like the others to fetch firewood. So she only returns with little, which she sells for between ₦150 and ₦300. This is what sustains her and her six-year-old granddaughter. “I buy some maize flour and, if the money is sufficient, I will buy a little dry fish and some Maggi cubes,” she says, revealing her secret. She eats only once a day, in contrast with twice at Gidan Taki. Another trick she has learnt is to reserve a portion of the meal in case her granddaughter complains of hunger before the next meal 24 hours later. Others with some money buy groundnuts worth about ₦20 for their children to keep them occupied before nighttime. Sometimes, the kids get extra food from begging.

Returnees in Baga and Doron Baga seem to be among those most familiar with food scarcity. Like in other places, such as Auno, Bama, and Gwoza, terrorists patrol the outskirts of the town and residents risk running into them if they travel beyond the military trenches. This means critical farmlands and rivers cannot be accessed.

“If you go to Baga now, you will see that women are begging in the soldiers’ camp. They are going to soldiers to get food from them. And the NGOs cannot go to that area because of insecurity,” one witness tells us. “Wallahi, you will see hunger, starvation in Baga. There’s one woman who used to sell danwake (a local delicacy made from bean flour) and people wait for her to finish selling so they can drink whatever water remains. The hunger is so bad, especially for little children.”

Desperation borne out of hunger manifests differently in Auno. During the rainy season, returnees were employed as farmworkers. Now, the only chance of survival they have is rooted about 20km away, close to the Konduga axis of the Sambisa forest — which has infamously served as a haven for terror groups. The returnees visit this region repeatedly to fell trees and fetch firewood, which they then sell. Some of the single women are said to have resorted to survival sex as well.

In Ngwom, Mafa LGA, where there is another resettled community set up by the North East Development Commission (NEDC), residents similarly rely on sourcing and selling fuelwood. They, however, tell HumAngle it’s tough getting anyone to buy. There’s also the risk of getting abducted by terrorists.

There are accounts of the state authorities promising to give a sum of money to those getting resettled, and then reneging. Gujja and others, for example, say they were supposed to receive ₦100,000 just as was shared in some camps, but they got only ₦20,000. “—They said they would pay the balance but, up to now, they’ve not paid.”

On top of this, the Borno government has banned Non-governmental Organisations from distributing relief items to IDPs in resettled communities as a way to build ‘self-reliance’. Last year, the World Food Programme signed up IDPs afresh for its food allowance programme and paid ₦18,000 to each beneficiary. But many say it only lasted for two months. They were told this was because of the government’s directives.

Enquiries sent to Borno’s Commissioner for Reconstruction, Rehabilitation and Resettlement (RRR), Mustapha Gubio, and the governor’s media aide, Isa Gusau, about the unpaid benefits and general welfare of resettled IDPs have not been responded to.

Boko Haram’s violent spree, new recruits

Insurgents are still in control of a sizeable part of Borno and their tentacles of terror stretch even further into other places. So, when displaced people are transported back to their home communities, they oftentimes become sitting ducks or are assimilated into the Boko Haram-governed spaces.

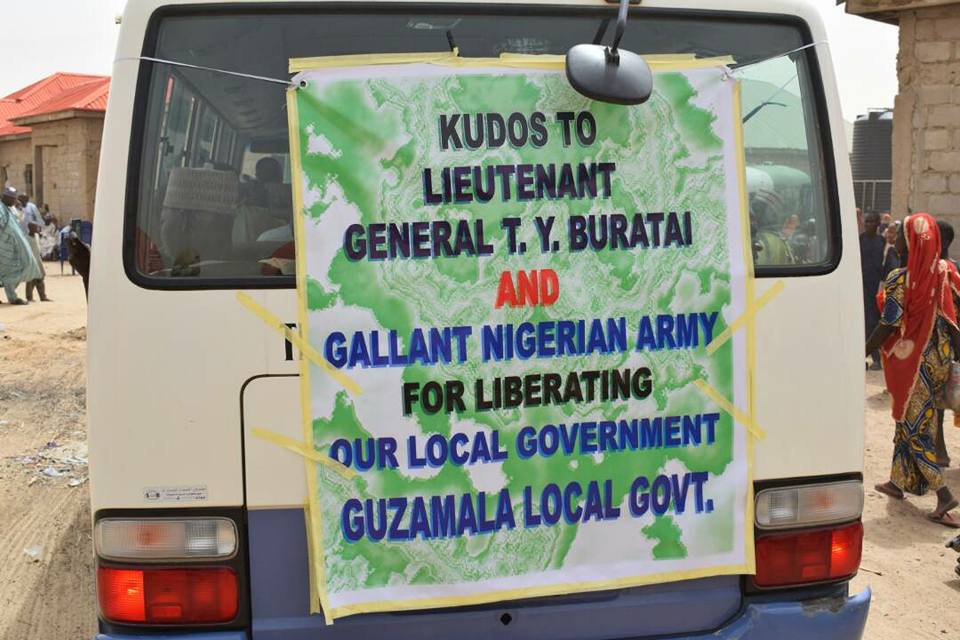

By the middle of June in 2018, when it was time to celebrate Eid al-Fitr, over 2,000 IDPs from Gudumbali, Guzamala LGA, had returned home after a nudge from the state government. They had previously sought refuge at the Bakassi camp in Maiduguri. The authorities promised they would be able to return to their traditional livelihoods of farming and fishing. The military promised them security and a ‘normal life’. What awaited them though was far from normal.

Less than three months after the relocation, ISWAP terrorists attacked the military base in Gudumbali, killing eight civilians in the process and forcing others to flee to neighbouring communities. The soldiers fled too, ceding control of the area.

The IDPs became displaced yet again as many made their way back to the Bakassi camp in Maiduguri. “They were chanting, ‘Mun kama garinsu gaba daya,’” narrated one of the survivors, describing the 12-hour-long attack. The phrase means, ‘We have taken over the town completely.’

The following December, ISWAP fighters again attacked Nigerian troops during an aid distribution exercise and killed 12 soldiers. Guzamala LGA is still under ISWAP control, with the terror group’s flags visibly hoisted in various communities and its laws reigning supreme.

HumAngle learnt from a local security source that, in Gudumbali particularly, over 500 youths were conscripted into ISWAP.

According to Gidew, sometime in January, four women in Shuwari “went to the forest and never returned”. Their tents have been given to others who need shelter. People suspect that the women decided to cross into Boko Haram territory, expecting to meet better living conditions.

The 2018 resettlement of displaced people to Guzamala took place under a different governor and a different Chief of Army Staff, but their successors have continued down the same thin layer of ice.

In Aug. 2020, less than three weeks after displaced residents returned to Kukawa, another community in Northern Borno, ISWAP struck. They similarly fought off the soldiers but did not stop there. This time, they also went after the civilians, taking hundreds of captives.

Being the former capital of the old Bornu Kingdom, the Monday market in Kukawa attracts traders from all over, including northwestern Nigeria and the neighbouring Niger Republic. It is now managed by ISWAP, which has introduced a second market day. “When you go to that market, you will see Boko Haram with their gun trucks stationed in different locations,” a local source informed HumAngle. “They are the judges. The people pay taxes to them. Everything in this Kukawa is under their caliphate.”

Terror attacks have been recorded in other resettlement areas too, including Ajiri, New Marte, Ngwom, and Shuwari.

Last August around 6:30 p.m., barely a week after IDPs from Gidan Taki settled at their new home, Boko Haram militants attacked the 195 Army Battalion stationed near the Shuwari site. One explosive landed behind Gambo’s shelter and he had to move to a new tent. “Some even left the town that night. We couldn’t sleep,” he recalls.

During one evening attack in Ngwom in mid-September, the terrorists again exchanged fire with the military. Bullets hit many civilians scampering for safety along the main road.

The resettled IDPs face a bunch of other problems too, such as the lack of easy access to water and sanitary facilities.

Those at the resettled camp in Shuwari say there are only three taps available for over 3,000 people. They are forced to fetch water from the Customs House IDP Camp, which is 3km away. Also, two months after they settled in, a cholera outbreak killed at least 41 people, about half of whom were children. Gujja, whose daughter recovered from the disease, blames poor hygiene, lack of a good toilet, and the rainy season for the incident. “We don’t have toilets here. What we have are toilets we dug by ourselves,” she discloses.

It is not all bad news though. Through the resettlement programme, hundreds of displaced households now have free access to spacious concrete houses constructed by state and federal agencies. Some also mentioned having access to land for farming.

Are the resettlements voluntary?

One claim state officials are fond of repeating whenever they speak about the resettlement efforts is that they conform to international laws, especially the African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of IDPs — often simply referred to as the Kampala Convention.

The law requires signatories such as Nigeria to “respect and ensure the right [of IDPs] to seek safety in another part of the State and to be protected against forcible return to or resettlement in any place where their life, safety, liberty and/or health would be at risk.”

Gubio told HumAngle last year that those resettled were given three destination choices: resettlement site, Maiduguri metropolis, and their home communities. The obvious flaw here is that remaining at the camp is not one of the options.

Affected IDPs who spoke to HumAngle did not think they had much of an alternative and see the governor’s instructions as binding. “When the government speaks, we listen,” one said plainly. Even after the resettlement, Gambo does not think the authorities care what he has to say.

“My opinions do not really matter because who am I? We who are IDPs are supposed to be given sympathy and a listening ear. That’s all we need,” he says in his frail voice. As if considering the odd chance that the government may listen, after all, he adds that they need help; “food especially.”

The suspension of monthly food allowances and aid distribution to IDPs may have also made them likelier to accept an alternative; any alternative. Many have not received support in over three months; some since Feb. 2021.

The Kampala Convention, just like the UN Protocol on the Protection and Assistance to IDPs, also demands that IDPs are consulted when it comes to matters relating to their protection, assistance, and resettlement. Some of those resettled deny that this was done.

“They just came and said, on Friday, that we should pack and leave. Just like that. No one asked about our opinion. Nobody told us why,” Gambo says. Returnees in Auno mentioned similar concerns to HumAngle last year.

There are no signs yet that the state government plans to slow down on resettling displaced persons or to modify its approach. On Wednesday, Feb. 2, Abuja inaugurated the Presidential Committee on the Repatriation, Return and Resettlement of IDPs in the Northeast to coordinate resources for the programme.

One morning towards the end of January, Borno State officials, in the company of soldiers and civil defence officers, visited the Dalori I displacement camp in Maiduguri, lined up the IDPs, collected their details, enquired about their LGAs, and gave them “beneficiaries token” cards. This was the pattern in now-evacuated camps, and the residents here are afraid of what is to come. One of their leaders tells us they are not interested in leaving since their hometowns are still not safe.

Back at the Shuwari resettled community, Gambo says the Boko Haram attack last August was the last straw for some of them who opted to finally leave Borno for other states. He is staying though, with his wife and eight children. The children, by the way, are increasingly scared of visiting the forest for firewood but have no choice if the family is to get through the storm.

Asked if he is worried the insurgents may return to attack the site, Gambo glances briefly in the direction of the door, causing a flash of light to land on his face. “Not really,” comes the reply.

“—We are just hungry.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter