‘When Is Father Coming Back?’

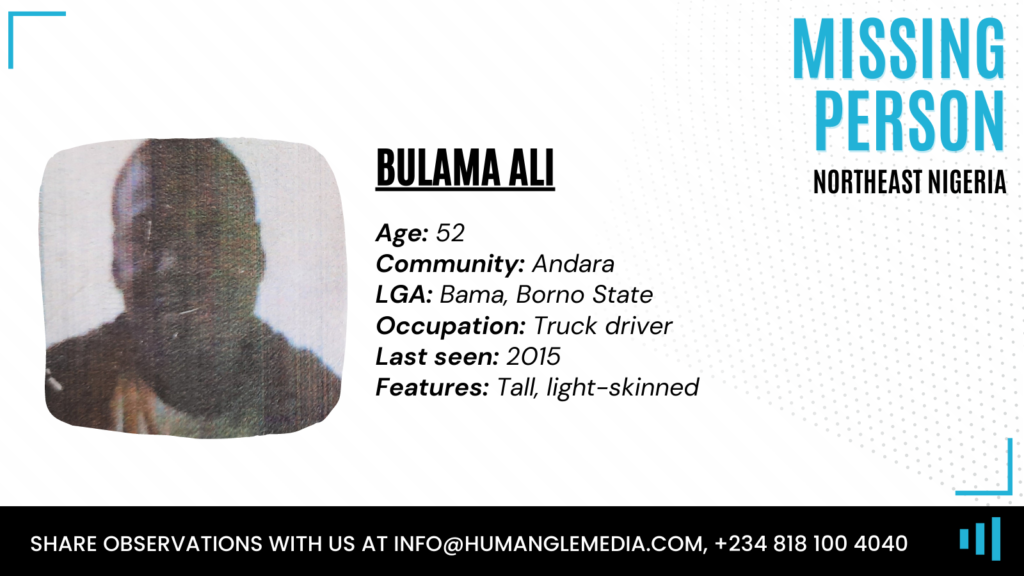

The story of a girl who has never seen her father and a young mother who cannot bear to live with another man.

Hauwa Bulama has never met her father. If not for his national identity card, she would not even know what he looked like. Each time she asks her mother about him, she gets the same response: “Don’t worry, he will come back. We are still waiting for his return.”

Aisa Modu, 25, was two months pregnant with Hauwa when she and her husband, Bulama Ali, fled Andara, a town in Bama, Northeast Nigeria. Members of the terror group, Boko Haram, had occupied the community and placed a ban on travelling. But thanks to military advances in 2015, there was eventually a chance to escape and the couple seized it.

They set out at night for Kulujia in neighbouring Cameroon, but Bulama did not make it back to Nigeria.

“They [security agents] separated seven men including my husband and started beating them. The following day, we were taken to Kumshe, leaving them behind. We have not seen them up to now nor do we know what happened to them,” says Aisa. “We don’t know whether the military killed them or they have been taken to a detention centre.”

The men, including one Mallam Abba Aji, were accused of transporting goods belonging to Boko Haram.

Yagana Aminaye, Mallam Abba’s cousin, recalls that the soldiers and vigilantes first stripped the men before beating them with thorny canes. “According to some people, the Cameroonian military brought two vehicles and took them away. But those in Cameroon said they didn’t see them,” she told HumAngle.

There are currently at least 24,000 people recorded as missing in Nigeria, according to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). The vast majority of these people went missing due to circumstances connected with the Boko Haram insurgency in the Northeast.

Aside from the forceful displacement of people from their communities, profiling and arbitrary arrests by military personnel as well as cases of unlawful detention have contributed to the menace.

Amnesty International observed in a report published in 2016 that after the Nigerian army regained control of places occupied by Boko Haram in 2015, its officers arrested hundreds of young men, especially people fleeing from communities in Banki and Bama.

“Witness testimony suggests that these arrests were arbitrary, largely based on random profiling of men, especially young men, rather than on reasonable suspicion of having committed a criminal offence,” it said.

The poor treatment of Nigerian refugees in neighbouring countries such as Cameroon has further worsened the situation. There are multiple examples of displaced victims of the insurgency getting arrested, deported, treated as terrorists, and detained without trial for many years.

When Aisa was returned to Nigeria together with other refugees, they first went to Banki. Two days later, they were relocated to the Bama Hospital Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) Camp, notorious for extreme food shortages and starvation during the period.

All this time, she was pregnant with Hauwa and eventually gave birth at the camp.

“It was a difficult time because we left everything behind in Andara,” she recalls. “I did not have even ₦20 but I met my mother there. She came with something that they used to look after me; that is why I did not face hunger or much difficulty.”

She spent 10 months in Bama and then returned to Banki with her family. There, her parents insisted that she remarried since she was still young. But she had a different idea. She would rather wait for Bulama to come back. So, last year, she left for Maiduguri, Borno’s capital, with the hope of escaping her parents’ constant nagging.

“He was always concerned about people,” she says about her husband. And it seems only fair that she extends the same courtesy to him now.

“—I am ready to wait for him.”

Moving to Maiduguri by herself, however, has its downside. Currently, her only means of livelihood is fetching firewood from the surrounding forests and selling it. She says she gets about ₦300 (about half a dollar) from this, which she uses to buy maize flour and sweet potatoes to feed herself and Hauwa.

Bulama is a brother to Yagana’s husband and he gave Mallam Abba, her cousin, the pink truck he drove to earn a living. He himself had a green Toyota Delta truck he personally used.

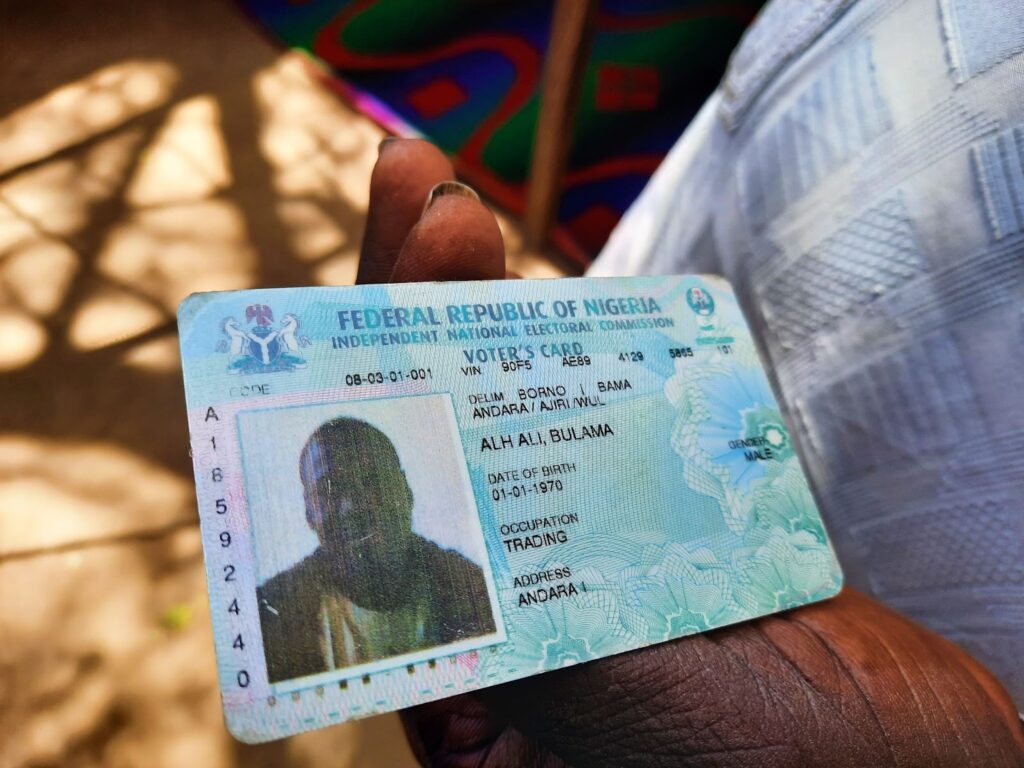

Aisa says he is 40, but his voter’s card states Bulama’s age as at least 52. He is tall and fairly light-skinned. He does not have any distinguishing marks on his body. But Aisa does not know for certain now considering how he was tortured back in Kulujia.

Aisa is unmistakably shy, fixing her gaze on the ground for the most part as she talks. She is quick to smile too. Asked how she met Bulama, her face spreads into a grin as though she is embarrassed to share the details.

“You know, I was not in Andara at first,” she says, playing with and staring at her fingers. “Our village is Tangalanga. Bulama used to come to Tangalanga on transit. He would come and go to Kulli market and always stopped by. Sometimes, he would come to our house and buy sheep. That was how we met.”

The two of them got married in 2012 and she says he’s been so good to her that she’ll like their child to emulate his qualities.

Hauwa is five years old now and she wouldn’t stop asking about her father. One time, Bulama’s junior brother, Ba’ana Ali, was released from detention and everyone happily went to receive him. “What about my father? Up to now, we didn’t see him and people have come from the prison,” Aisa remembers her daughter asking. “I told her to exercise patience, that we are still waiting for his return.”

It is not only Hauwa who cannot wait to see Bulama again. Aisa herself gets giddy at the thought of his return.

“I just pray for my husband to return. I would be very happy to see him,” she says, smiling shyly at first and then laughing so heartily it’s childlike.

This report was produced in partnership with the Open Society Initiative for West Africa (OSIWA) under the Missing Persons Register’s Population and Amplification Project.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter