What Happens When A Displacement Camp Is Emptied Of People?

Hundreds of buildings. They used to be shelters for people fleeing the violence in their home communities. They are now shells of memories and, without urgent action, risk becoming even more wretched.

The Dalori II displacement camp echoed with life only last year. Traders lined the dirt roads with groceries, firewood, and clothing accessories. Young men played football on the field adjacent to the school painted in pale blue. Women sat by the shelters to embroider caps as they watched over their babies. If there was no vehicle to chase after, the children delighted in dragging polythene kites either through the soil behind them or the sky above.

This vast camp, located on the outskirts of Maiduguri in northeastern Nigeria, now lies barren. The only sign of life resides in the security personnel manning the gates to prevent those petty traders, those athletic men, those enterprising women, and those young kite fliers from making their way back in.

The gates used to be flung open as people entered and exited freely. Today, even though parts of them have been torn away from their joints by the forces of nature, the iron sheets still lay precariously in the way as barricades to prevent unauthorised access.

The government of Borno state insists the days of providing camps for people displaced by the years-long Boko Haram insurgency are over. So, a few years ago, it started shutting them down, starting with those in and around the capital city of Maiduguri. This is despite the observation from non-governmental organisations that the decision has pushed hundreds of thousands of people into “deeper suffering and destitution”.

According to the governor, Babagana Zulum, the camps have become fertile ground for prostitution, procreation, and drug abuse. He has also said that closing them will encourage the IDPs to “earn their means of livelihood by themselves”.

“The governor told us they were going to dismantle the camp, that we should return to our communities,” recalled Bukar Ali, 57, who used to live in the Dalori II displacement camp. “He said people would become lazy if they kept staying there and depended on NGOs for food.”

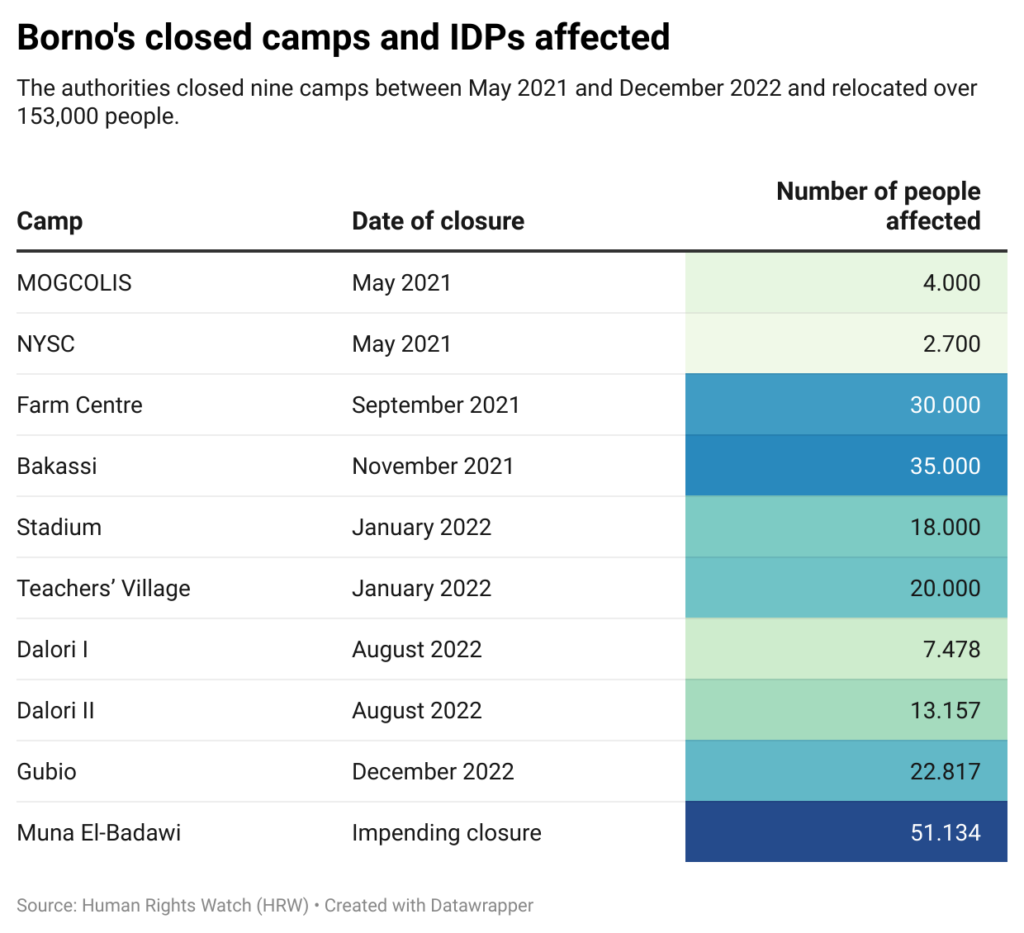

The authorities closed nine camps between May 2021 and December 2022 and relocated over 153,000 people. Many of them have moved to sites across the state, while others chose to remain in host communities around the capital city. Resettled IDPs in all these places have narrated experiences of hardship, starvation, and uncertainty. They no longer receive stable humanitarian aid, and their attempts at squeezing a living from farming or fetching firewood are blocked by terrorists waiting for them to venture far enough into the bush and farmlands.

But it is not only the displaced people who face tough, uncertain times. Many of the camps they left behind have suffered a similar fate.

Google Earth images show that the Dalori II displacement camp has about 210 housing units. The houses were built in 2014. The following year, white tarpaulin tents started springing up at first close to the southern fence. Gradually, they spread all over the compound. In 2022, when the camp hosted over 13,000 people, there were hundreds of such temporary shelters. By August of that year, when the resettlement exercise took place, they had all vanished. Only the cement structures remained.

When HumAngle visited the camp last September, we noticed many of the buildings had deteriorated. Some rooftops were completely blown off or had started to cave in. Some amputated aluminium roofing sheets tossed and groaned in reaction to the wind. Congregations of weed had started to grow in the porches, around the buildings, and inside roofless structures. The water point no longer had a large overhead tank nor a queue of jerricans and eager women and children.

From a distance, the school still basked in its unmistakably pale blue colour. But it is only a matter of time before this, too, is lost to decay.

The security personnel stationed at the camp said the only people who lived there were 12 police and Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) officers, alongside some of their families. They farmed inside as well. But the large emptiness has invited in various reptiles, especially snakes. “On windy nights, you would hear the cracking sounds of roofs falling apart,” one of the officers said.

Farm Centre (Gidan Taki) displacement camp along the Maiduguri-Mafa Road faces a similar problem: ghost houses and outgrown bushes. The available expanse of land has been converted into a maize farm.

Security agents stationed at the camp said a commissioner visited recently, instructing them not to allow people inside the property and stating that work would soon commence.

“The place is empty. If you see anybody here, it is security and farmers,” one officer said. The wisdom behind farming inside the camp, he claimed, is to prevent weed infestation, which could worsen fire outbreaks.

The same fate has befallen many of the other emptied camps across the city.

The government explains that this is because not all the structures necessarily belong to it. Some belonged to private individuals or state institutions.

“Once these IDPs left, definitely the properties and structures are going back to the legitimate owners, either the philanthropists or the government itself. So the issue of wastage does not even arise,” said Dr Barkindo Saidu, Director-General of the Borno State Emergency Management Agency (SEMA). “The government will not tell you what to do in your house or in your farm unless what you intend to do is illegal.”

For example, he said, the Farm Centre camp belonged to the Mohamet Lawan College of Agriculture, or rather agricultural exchange workers. With the IDPs gone, the space would be returned to the owners “to continue with their official activities”.

He added that members of the host communities would continue to use WASH facilities in these camps, such as boreholes.

It is true the displacement camps have different origins, most of them starting off as something else. However, HumAngle’s research showed that many were originally government projects.

The Dalori I and II camps were part of a housing estate project the state commenced in 2013 under former governor Kashim Shettima. The goal was to build a thousand homes, about 250 in each location. Gubio camp on the outskirts of town and Bakassi camp along the Maiduguri-Biu road, where the construction of houses had reached a more advanced stage, were also part of this project. Teachers Village camp, comprising over 200 houses, was intended for teachers upon completion but was eventually allocated to IDPs from Ngala and Kukawa. Stadium camp was located at the site of an abandoned ultramodern stadium project initiated in the ‘80s. Finally, the Mohammed Goni College of Legal and Islamic Studies (MOGCOLIS) camp was situated within the grounds of a public learning institution in the heart of Maiduguri.

HumAngle gathered that earlier this year, the Borno state government set up a committee to assess the value of the houses in the closed camps. The purpose was to potentially sell them at affordable rates to members of the public, who would then develop them independently. Sources familiar with the development claim the committee has submitted its report and is awaiting the government’s decision.

Many of the displaced people who used to live in the Dalori II camp now find shelter in the vicinity, setting up camps wherever they are welcome.

Bukar Ali found refuge in the camp for seven years. When he mentioned this, he pointed in the direction of the camp and smiled. It was tough at first, but then humanitarian organisations started coming with food items and other aid. After the camp was closed, he opted to hang around rather than return to his ancestral home of Kirawa, a community in Gwoza about 130km east of Maiduguri. It is not safe there, he explained.

“Most people from our village are now in Mora and Kolofata in Cameroon. But there are few people living near the market with the military. Recently, a man went there, and that night, he was butchered with a machete. They also abducted his daughter. He is now in the teaching hospital and has even lost his sight.”

But staying near Maiduguri has proven to be unsafe, too. Attacks by terrorists in remote areas have made accessing farmlands and forest areas risky for displaced people.

“I am supposed to be on the farm now, but I can’t go because of insecurity. You only see us here because we are afraid of going,” Bukar said that afternoon in September.

He had not been to the farm in ten days. In the first week of that month alone, four people he knew were abducted. This is despite the farm being less than two kilometres from the main road. The terrorists would demand ransom running into hundreds of thousands of naira, foodstuff, and phone top-up cards. So as not to stay completely idle, Bukar secured a small parcel of land by the roadside, where he planted sesame seeds. He reckoned it was better than losing his life in the bush where his corpse might never be discovered.

“Will someone be able to take care of themselves in this condition?” he asked.

Since the closure of Maiduguri’s formal displacement camps, many IDPs like Bukar have chosen to remain in host communities in and around the city, mainly because they fear they would be in greater danger if they returned home.

A survey conducted at the Dalori I and II camps by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in 2022 showed that only 15 per cent of the displaced people said they were going along with the resettlement programme because security had improved in their rural homes. The majority said they were leaving because they had no choice and no access to humanitarian support.

Some returned to Maiduguri after their resettlement because of attacks and ill-treatment from insurgents. Some, hearing of these experiences, never bothered to leave the metropolis. So, unable to afford rent in the town, they set up shelters wherever they were accommodated. This has mounted pressure on host communities such as Kofa, which adjoins the Dalori II camp.

Bulama Modu, the village head of Kofa, disclosed that his community has grown from just 47 households to more than a thousand because of the influx of displaced people, especially since the closures. This has put a strain on resources such as water and farmlands. There is only one water point serving the community and safe farmlands are hard to come by.

“If somebody has come and does not have anything, we have to give them a portion of land to plant groundnuts, beans, and whatever they want. But we have a shortage of land. We can’t go far because of the situation with the insurgents,” Modu explained. “We have to manage the little we have around.”

How does Bukar feel whenever he passes by the old camp that is now closed off to him? His answer shows he seems to have accepted the events as being outside his control. He is, after all, but a “common man”.

“We have nothing to say,” he replied. “The place belongs to the government. The person in charge said they don’t want to see us; what can we say? Even here in Kofa, the government has the power to chase us away. The leaders decide what they want.”

Isa Kamsulum, an IDP who was resettled out of the Farm Centre camp, responded by scoffing when asked what he thought the government would do with the houses they left behind. It has never been about the houses for him but the safety they afforded — which was absent where he came from. Back in his hometown of Bama, before the dark days of Boko Haram, he said, he used to harvest between 80 and 120 sacks of produce in one season. He was not poor.

“So what will I now be doing here?” he asked.

“If our villages were safe, even if you rebuilt the Farm Centre camp with new houses, nobody would come. We would all go back to our communities.”

Additional reporting by Abdulkareem Haruna.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter