Reporter’s Diary: Understanding The Different Faces Of Drug Addiction

This reporter spent five days in Kano, northwestern Nigeria, conversing with drug addicts across various demographics to get a sense of their journeys. Here, she gives a personal account of the trip.

During the last 10 days of Ramadan in the year of Covid, my baby brother was in the habit of leading the house in night prayers, known as Tahajjud among Muslims.

It was for many reasons: he had memorised the Qur’an and so could ensure its completion during Tahajjud prayers before the holy month ended, which was usually the objective. But he was also a fast and passionate reciter. His voice inspired people to endure the hours-long prayers. Sometimes, it even moved them to tears. He used to lead the community mosque, but that year there was Covid, and mingling with crowds was not advisable. And so, every night from 1 a.m. to 3 a.m., we filed into a line behind him at home.

That night, the last of Ramadan, as he rounded up the prayers in the last Raka’at, he recited more passionately and fervently than he had done in the past days. His hands were cupped in front of him; they shook as he supplicated, his voice dripping with a kind of earnestness that shook me to my core, his shoulders quaking. The small congregation he was leading was largely familiar with most of the night’s supplications. But then he ventured into a supplication that many people did not know. I did not know it myself, but I suspected it was a personal prayer being rendered in Arabic because he understands the language reasonably and perhaps because he did not want us to know what he was praying for. He said it repeatedly, his cupped hands shaking, his voice rising and trembling simultaneously. Then suddenly, my father, whose head had been bowed in prayer the whole time as he stood behind him, raised his head to look at his son. And then he began to weep.

At first, I thought he had been simply overwhelmed by the earnestness with which my brother was supplicating or that perhaps he had become overcome with piety. My father spent the rest of that day in a solemn mood. There were times I looked at him and found him lost in thoughts as he stared into the distance.

That night after we broke our fast, I went to him to know what was wrong. And then I learned why he had wept during prayers: The last supplication my brother had made that day was him begging God to take his drug addiction away from him.

My father says it broke him. He was not alone.

It was a personalised version of the prayer he himself had encountered during his numerous trips to various clerics seeking help treating his son’s addiction. Before then, he had tried rehab; he had pulled him out of university to monitor him more closely. He had tried therapy and counselling. None helped. And so he had turned to God. He did not realise that the boy had, too.

It had been a long, long journey. One that had strained my relationship with my brother, strengthened it, and then strained it again. It had upturned everything I knew to be true about life, about love, and about perseverance.

There is no other way to say this: drug addiction is a terrible thing. It changes the addict, the people they love and who love them back, and how their family loves them. It is difficult to hold a person you love through spasms during their withdrawal phase, choking on tears as you bear witness to their helplessness, as their legs twitch, knowing even in your holding that you cannot help them, but finding comfort in the fact that they will be fine after that phase, only to watch them slide back to the vice later. It is difficult to understand how someone would weep into your hands one night, reminiscing on the ways drugs had destroyed their life and swearing they would never go back to it, only for you to perceive the smell of cigarettes from their breath the next day.

There is something that that does to you. You begin to find the situation hopeless. You begin to find them hopeless. Sometimes, you come near resentment. But years of dealing with it teaches you something: that it is is not a thing they can help, oftentimes. And because love is seldom a thing that breaks in the face of imperfection, you learn to love them through it, eventually.

And so, the night before I left my apartment in Abuja, Nigeria’s capital, on a reporting trip to Kano in northwestern Nigeria to investigate drug addiction in the state and how people and their families live through it, I sat my brother down to get insight that only he could have given me. He had been visiting at the time.

We had had variations of that conversation over the years, but none had been as honest and lengthy as that night’s.

“It’s a lonely journey,” he told me, not looking me in the eye, drawing imaginary lines on the bed. “You lose yourself, you lose your education. You also become a liar. It’s fucking lonely.”

He reiterated that it was not that he had not tried his best to stop; it was that once your body is accustomed to a thing, it fights you for depriving it of it. Not many people can endure that fight and come out on top. I have watched him lose it many times.

It was why that last night in Ramadan, he had asked God for mercy.

***

My flight to Kano was delayed by several hours. When I arrived at the airport, it was past 9 p.m. I had googled a list of hotels to lodge. This city I had once spent five years of my life in, I still needed the help of the internet to get decent accommodation. By the time I arrived at the hotel, I was tired and weary. I had called them to book ahead.

When I was shown to my room, I was so confused. It was dirty, old, and looked like insects could come running out of corners at any moment. The mattress was on the bare floor, and the TV looked like a laundry basket. The place looked like something out of a 1980s Nigerian movie.

And it cost over ₦20,000 for a night.

I decided I could not sleep in that room. I texted some of my best friends in a state of panic and told them the state of the room. “I can’t sleep here,” I kept saying. I was nearly in tears. I sent a long voice note to Ruka and another to Zainab. Everyone advised me to endure that night until the following morning and find a better place as it was late already. I said okay but still planned to leave. My baby sister was schooling in Kano but lived on the other side of town, where her school was located.

I texted an acquaintance, Mubarak, who I had planned to move around with for the assignment as he was familiar with the people I was looking to interview. He would later become a dear friend. I said I needed to leave and find a better place and asked where I could find it.

“No,” he texted back. “Pass the night there. It’s already late. It’s not safe out there.” Then, as if sensing from my delay in responding that I wasn’t taking him seriously, he typed again, “It’s late already.”

I could feel the urgency in his tone. I looked at the clock, and it was 10:30 p.m. It didn’t seem so late to me, but if a resident of the place said it was, he definitely knew what he was talking about.

I did not sleep the whole night. The following morning, as early as 6 a.m., I left the hotel. When I arrived at the new place, I had no worries as to the quality of the rooms; it’s a big hotel in Kano, likely the most popular. It was also located in a highbrow area. I only agonised over how the cost would eat into my funds. To my surprise, it cost the same price as the previous hotel, despite being far better. I even got a discount when I said I was a journalist. I nearly wept with relief and joy when I got to the room. It was so spacious, beautiful, and quiet.

Later, I headed to Bayero University, where I had planned to meet with Mubarak. My baby sister also schooled there, so I went an hour earlier than I had planned with Mubarak to enable me to spend time with her.

When he arrived, he had a face mask on; I had one too but took it off when he said he was nearby. He was very pleasant.

My first respondent, Terror, arrived soon after. He had such a babyish, cute face. I see his face even now, smiling guiltily as he told me about his numerous smoking sprees.

I sat beside him on a concrete slab after Mubarak had introduced us. I plastered a huge smile on my face and exuded warmth. He couldn’t seem to stop smiling. I think we connected instantly.

“So,” I said, “tell me your story.” And he laughed. But he did tell me. I heard about how he started smoking at 10, how he had learned from his big sister, and his parents’ numerous attempts to help him out of it, including having him locked away at a torture house. He told me about spending his youth in a university and yet never acquiring so much as a secondary school leaving certificate. He told me his real name and said no one had called him that in years.

He told me about his ex-girlfriend, how she would travel away from home just to be with him, and how her brother would come to drag her away and even once had him arrested. But each time, she would find a way to return to him. He even talked about the sex in passing.

As we spoke, a tall and heavily built woman passed by, and Terror looked at her with surprise. He told me he knew her from way back. She looked to be in her 40s. “She used to run a local restaurant I frequented a lot. I haven’t seen her in years. But we’ve smoked together a few times,” he told me.

“Word?” I said, incredulous, and we started laughing. “Watch this,” he said, and then he called out to her. She looked at us from afar and squinted her eyes with suspicion, unable to recognise Terror. He lowered his hood, and slowly, her face lit up when she realised it was him. She approached us instantly.

“Auwalu,” she kept calling. “Is this really you?” And he kept smiling. They bantered for a bit before she left.

Afterwards, Terror led us to his neighbourhood, where I met more of his friends and got a fuller picture of the genesis and chain supply of their involvement in drugs. I met a man who was so kind and open to me, but whom I later learned had murdered many people before, especially as a thug during elections. The knowledge ran a chill down my spine.

He told me he was 47. And when I asked how his family took his drug addiction, he asked, “What family? I don’t need a family when I have drugs.”

He said he had never been married nor had any kids before. But he did have a girlfriend he loved very much. She makes him happy, he said.

“My only problem with her is that she wants me to quit drugs,” he told me.

“She is always disturbing me about it. She has even threatened to leave me if I don’t stop. Imagine that. But honestly, I want to marry her. So I am trying to minimise it. I told her I can’t stop. But I am trying to minimise it.”

I met with another set of men still within the neighbourhood; a young man with a leg swollen from injecting himself too much with pentazocine. He could hardly walk, yet he admitted that he had still not stopped injecting himself.

I returned to my sister, who cooked for me and fed me, before returning to the hotel.

The next day I set out at 9 a.m. I was meant to meet someone who would link me up with a man running a torture house where drug addicts were being held and subjected to torture for ‘rehab’. But he disappointed and did not show up. That would have been a total game-changer and improved the weight of the materials I would have walked away with. But I decided I would not let it dampen my spirit. I would learn later that reporting trips were usually full of dead ends and fixers who disappoint.

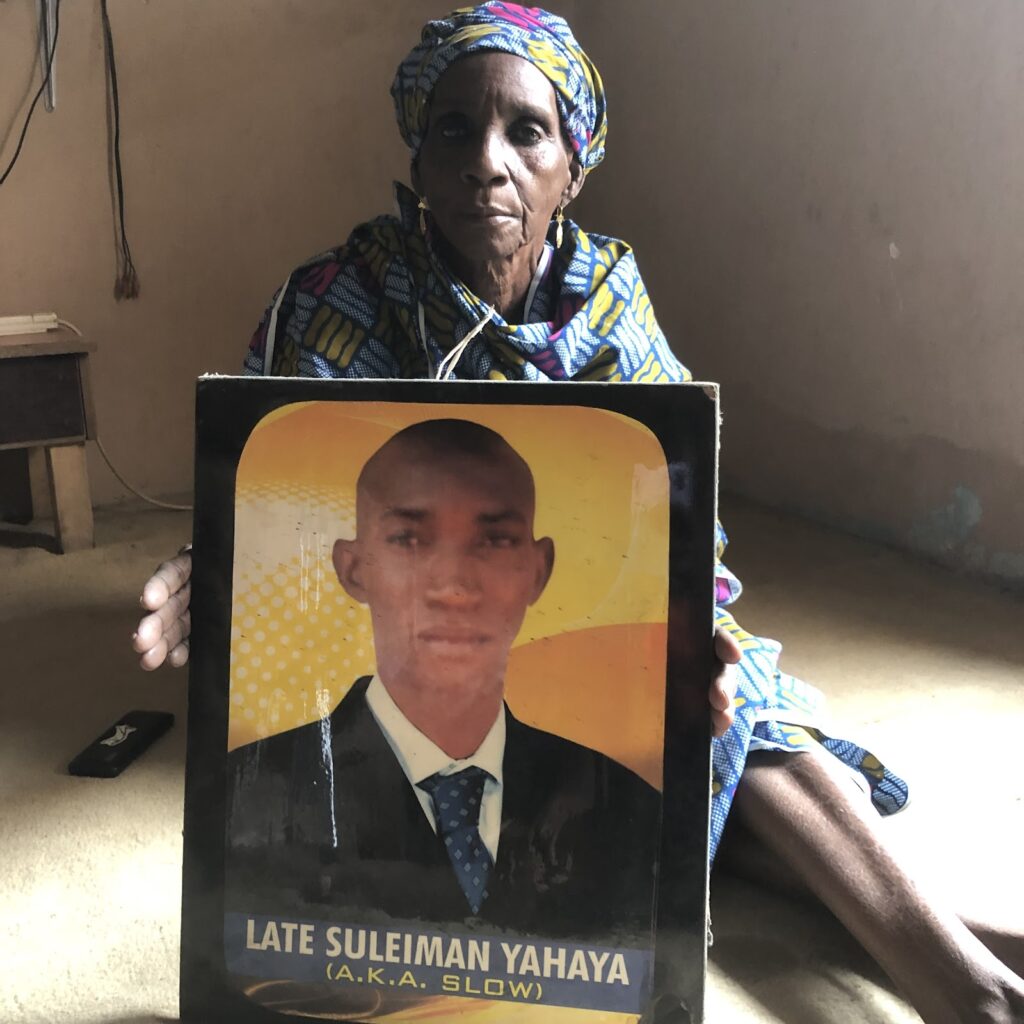

I found my way to my second respondent—an elderly woman who had lost her son, Suleiman, to drug addiction. I had heard of her story and had wanted to meet her for years. The first time I heard about her, I was moved by her resilience and strength. We had talked on the phone a few times, and I was finally meeting her today. I couldn’t wait.

I lost my way a few times but eventually found the correct address.

She was so smallish, so pleasant. She offered me soda and even though I don’t drink it, I drank it. I told her why I was there again, and she nodded in understanding as I spoke. And then she told me her son’s story.

When she talked about how difficult it became to love him wholly because she did not understand why he couldn’t just stop taking drugs despite what it was doing to him, I understood what she was talking about. When she talked about how she eventually realised that he could not help himself and resolved to love him through it, I understood that too.

When she talked about how he had finally gone clean and was finally getting his life together, I was full of hope. When she talked about how he still ended up dying, I went eerily silent.

I did not know what to do or say in the face of that kind of tragedy.

He had fought, and he had won. And he still died. I could not imagine what it was like to experience.

When I arrived at Sabon Gari to speak with some women sex workers, I didn’t even know where to start. I had never seen so many women smoking so casually before. But somehow, we managed to have a full conversation.

From there, I went to a brothel to observe. I tried to take a few clips, but it was too dangerous. I already stood out with my iPhone and fine dress and fine bag. I left shortly after.

Mubarak led me to different respondents on another side of town.

They were so kind to me. They offered me food and drink, which I turned down, but I watched them eat. It was a little scary to be the only woman amid so many men who were high and in such an enclosed space. I turned on my location and sent it to my sister. Then I texted a couple of people to let them know where I was.

As I sat watching them eat, one of their friends came in. He took one look at me and said, “you’re a journalist.”

I started to laugh. I will never know what it was that gave me away. He was eager to talk to me and very honest, too. I will call him Samad.

Samad told me that an hour before he was to undergo surgery to have the excess codeine in his body system removed after the substance began to cause him serious health problems, the doctors explained to him that it was important that he not eat or drink anything before the surgery. They did not explain to him that “anything” included the substance that had put him in the situation in the first place and for which he was being operated. Perhaps, because it seemed obvious enough.

After the doctors left his hospital room, Samad put a call through to his dealer and begged him to bring him a bottle of codeine as fast as he could.

It was not that he wished to die, he said. He knew it was bad for him, he recognised the pain it was causing him, and he did not wish for it to be prolonged. What he didn’t know was how to stop.

Though heavily under the influence of anaesthesia during the surgery, he recalls that the doctors could tell that he had indeed drunk more codeine. “They said ‘why did you go ahead and drink despite being told not to?’” he told me.

Hours after the surgery, as he lay on the hospital bed in the room allocated to him, recuperating, he found a way to get the substance again.

“I still found a way to get it. I could not stop.

“But you know one thing? I am grateful for the fact that I am actually not addicted,” he said with a straight face. His friends around him burst into laughter.

“You are not addicted?” I asked.

“Wallahi kuwa, I am not addicted. If I see that I am addicted like this, koh? I’ll just stop taking it. But I really thank God that I am not addicted.” He did not appear to be joking.

It made everyone laugh again. It made me laugh too.

My session with them was one I would never forget. It was rich. Once, another of their friends came in. I instantly knew who he was because he looked exactly like his father, a famous man in Nigeria. But I did not show that I recognised him. And when later he volunteered the information of who he was, I tried to respond with the right amount of shock. We had a long conversation.

That day, I got to the hotel at nearly 9 p.m. As I sat in the tricycle that took me back, the wind slapping against my abaya and my face, I was taken back to my years in this same city as a law undergraduate at Bayero University. I was mostly introverted, but sometimes Ruka and Farida succeeded in dragging me out at night. We would go to Sabon Gari for ice cream at night and return to school. Once as we made the walk from the school gates to the hostel where they stayed, we suddenly began to dance in the middle of the road. It was the year of the shaku-shaku dance and the science student song. A boy passing by asked to compete with Ruka as she danced. She beat him hands down. The memory made me smile, and I was grateful for my facemask.

***

On my last night in Kano, I followed Mubarak to his family’s home and said hello to his mom and sisters before I headed back to the hotel. They were as pleasant as he had been to me. They found the fact that I was a lawyer yet practising as a journalist fascinating. They did not question it, as other people might have done.

The following morning, as the plane touched down in Abuja, I breathed a sigh of relief and thought, “good to be back home.”

It was the first time I became aware that my heart had begun to think of Abuja as home.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter