The Agony Of A Mother Whose Son Died From Drug Addiction

She came to understand that the addiction was not exactly something he could stop on a whim. This realisation brought her to one truth: only love and compassion could help him. Not casting him away, not abandoning him, not disowning him. And so she resolved to love him through it.

On the morning of the day Suleiman Yahaya died, he had been singing the lines of popular Nigerian song ‘Sweet Mother’ to his mom.

Sweet mother, I no go ever forget you, for all the suffer wey you don suffer for me.

It was a Saturday. He had just secured a job with the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) and was slated to resume the next Monday. It was huge for him, for his family, and there was a festive air around the house which was located in suburban Kano State. And so when he left her out in the compound where she had been cooking Spaghetti, and went inside the house to press his clothes which he hoped to wear to work, only to begin yelling her name moments later, she ignored him.

“Mama! Mama!” he kept calling out.

“Usually, he would call out my name and, when I go to him, he would say something silly like, ‘Oh, I thought you went out ne,’” she says fondly, the corners of her thin lips tugging into a smile. Even at 37, he had an almost child-like love and obsession for her.

As he continued to call out, and as she ignored him, his older sister thought his voice sounded distressed, and so went inside to check.

She met him coughing blood, and she started to scream. It was then Maman Sani knew something was not right.

She abandoned her cooking and hurried inside.

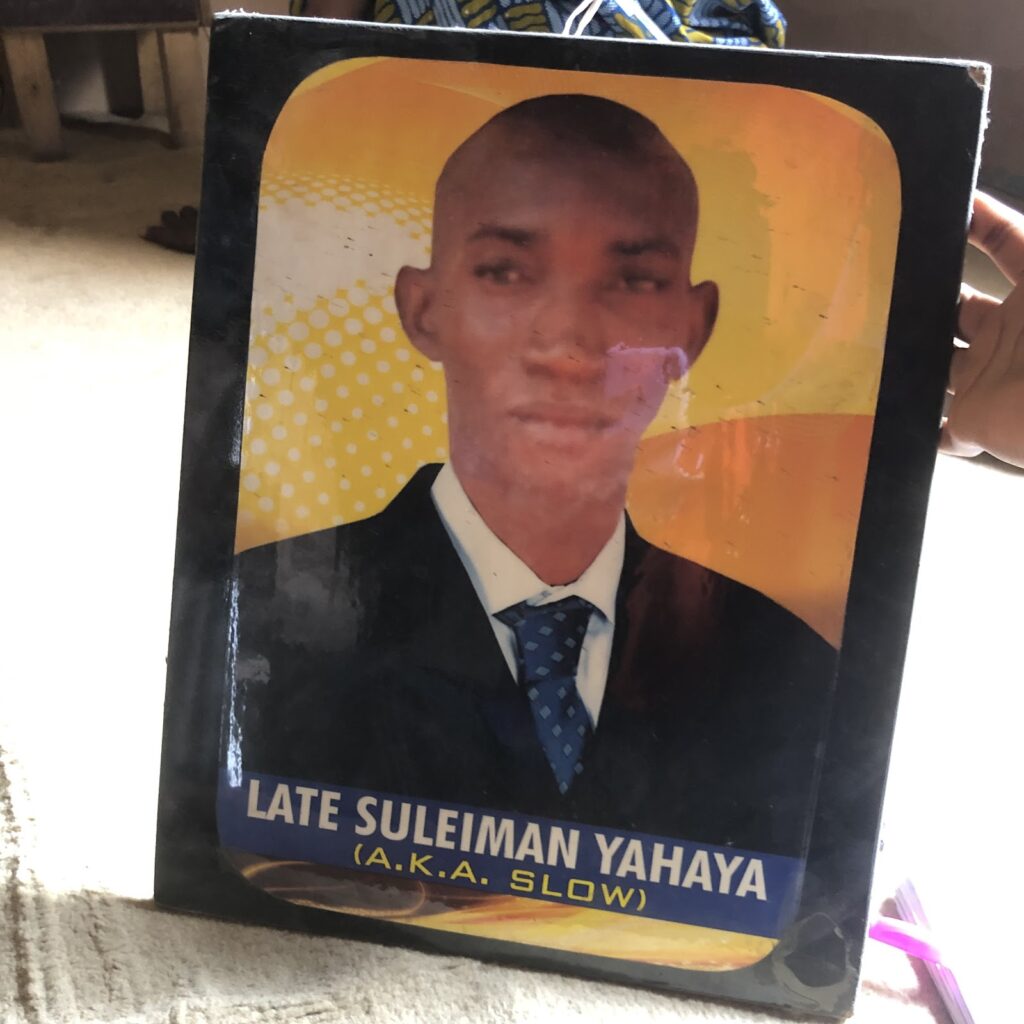

Who was Suleiman Yahaya?

Suleiman had many nicknames. He was called Slow by his friends. He was called Mai Unguwa because of his excellent mediation skills that enabled him to settle disputes between married couples despite being unmarried himself. He was called Daddy. And at some point after he got into drugs and began to badger his mother endlessly for money while he was away at school, with a text that always said, ‘Mummy, please send me some money,’ the woman nicknamed him Mummy Please Send Me Some Money.

He was also very good with Mathematics and loved to solve equations. During weekends, even as a child and then right into adulthood, he would gather children from the neighbourhood and teach them.

“If you see the way children used to fill up this house for his Maths lessons,” his mother recalls, the pride still rich in her voice even after all this time.

While he was a student at Government Secondary Commercial School, Kano, he fell into a circle of friends who were into drugs. It could have been an unbearable urge for adventure, a nagging curiosity, or simply peer pressure, Maman Sani does not exactly know, but Suleiman joined them.

Like many, his doorway into drugs was cigarettes, then he progressed to Marijuana, and slowly to other drugs. He was a teen at the time. When it got so bad that teachers felt they could not handle the situation on their own, the school privately invited his mother to talk about it. She was dispirited.

“I didn’t even know what to do, and even his father could not help, because he’s a drug addict himself. So how could he possibly ask him to stop? When I even asked him what we could do to get Suleiman to stop, he said I should pray for him. And I said ‘the same way I pray for you to stop, right?’” Maman Sani remembers.

So she turned to God, while also admonishing Suleiman every chance she got. She went back to his school privately and told his teachers to please whip him if they ever found him smoking or doing drugs. He was unaware of that visit.

One day, Suleiman came back home with welts on his body from having been flogged at school, and she ignored him.

“He came to me, and he started talking and stammering. He said, ‘Mama.’ I said yes? I acted as if I did not see his scars. And he said, ‘At school today, ba?’ And I said yes? What happened? And he said, ‘Some people were smoking; it’s not as if I was smoking with them; me, I was just sitting amongst them, but a teacher saw us and assumed I was smoking too, so the teacher flogged me.’ He expected me to give him sympathy, but I did not. I said a thief’s friend is also a thief.”

He urged her to go to the school and fight for him. She declined. He complained further that he was the only one amongst the cohort who had been flogged. In response, she told him that it was because they loved him. “And I said I really thanked God that I had people who loved my child for me and were helping me to raise him by disciplining him,” she says. “Because it takes an entire community to raise a child. A child belongs to everyone. Not just to his parents… So, you see, no one could ever say that I did not do my best to save him. I did all that a mother could possibly do.”

Though he promised her many times that he would stop, and though he did try many times to stop, there were days when he would return home in the evening, his eyes wholly reddened and his head bowed to hide it. He would meet her in the living room, murmur a greeting, and then hurriedly proceed to his own room without looking at her. On days like that when he refused to meet her eyes, she knew immediately that he was high.

Sometimes, she would, in frustration, begin to scold him. Suleiman would then earnestly beg her, asking her to forgive him, and promising once again that he would stop.

“He really loved me and was fond of me. He never wanted anything that could upset me, so whenever he saw that I had gotten angry, he would start begging me.”

She came to understand that the addiction was not exactly something he chose and was definitely not something he could stop on a whim. This realisation brought her to one truth: only love and compassion could help him. Not casting him away, not abandoning him, not disowning him. Only love and compassion. And so she resolved to love him through it.

“Sometimes, you would see parents casting out their children, especially when their daughter falls pregnant. They would kick her out of the house. Where do they expect her to go?”

After secondary school, Suleiman proceeded to Federal College of Education (FCE), Bichi, in Kano and it was there he met with a gang of drug addicts whose reputation was worse than that of the friends he had left behind in secondary school. ‘The true drug lords,’ Maman Sani calls them.

Suleiman’s addiction worsened; he ventured into drugs that he had not known before and even to alcohol. He developed a drinking problem.

While Maman Sani had always been aware of the helplessness of the situation, with the faint knowledge that there might never be redemption, it was not until she learned that he had started selling off his foodstuff at school to be able to buy more drugs she realised how deep the problem had become.

“It was from there that I knew that only prayers could help.”

Then, he got sick.

Battling tuberculosis

First, he started to cough repeatedly and consistently. It was so bad that he would sometimes cough out blood, a condition known as hemoptysis. It lasted for up to three months. He was 30 at the time.

She took him to the Infectious Diseases Centre, Kano, where he was diagnosed with Tuberculosis.

He was subjected to medications that involved him having to take 60 doses of injections over the course of two months. Not minding his age, she made sure she went with him to the hospital to get all the doses, to ensure that he never missed any. And then when he started to falter, she got the doses herself and started to administer them to him personally at home. This was possible because she had a medical background. Afterwards, he was placed on medications that lasted a month.

Tuberculosis is rife in Nigeria. Yearly, about 245,000 Nigerians die from the illness. It is reported to account for 10 per cent of deaths in the country. These figures reflect that Nigeria has the highest number of TB cases in Africa and the third highest in the world. While smoking is not the singular cause of the highly infectious disease, it is a major cause.

“So, a person with TB has an accumulation of mucus in their lungs because of bacterial infection, which leads to an inflammation of the area, which makes him cough repeatedly to get rid of the extra mucus, which has no place in the lungs,” a nurse based in Kano explains.

“Hemoptysis is something that has to do with the lungs. There is a tissue called the cilia that propels mucus from your lungs up your throat so you can cough it out. When you smoke, the nicotine kills it. Asides that, it also kills linens and that’s why you can get lung cancer from smoking. When a particular tissue is inflamed, it swells, blood comes there — white blood cells trying to fight it and then ending up accumulating. So when you cough out blood, you’ve probably injured your lungs. Anything that bothers your lungs can make you cough out blood, including pneumonia.”

Smoking damages the lungs and can therefore cause hemoptysis.

“The doctors warned him to stop smoking and drinking, otherwise the TB would come back, because it is actually a recurring illness,” Maman Sani says.

The sad part about the illness, however, is that even after successful treatment, a person who has suffered it before remains prone to contacting it again.

For a while after he completed treatment, he successfully stayed off drugs. He was able to finish his education at the FCE and then proceed to Bayero University, Kano, to study Accounts & Auditing.

However, after some time, he went back to drugs, and it was so bad that he was unable to finish his degree at the university. His tuberculosis also became recurring. This time, his motypromised him she would not help him nor go with him to the hospital for his appointments.

“I told him that since he wants to kill himself, he should go ahead,” she remembers. Her anger could only last for a little while. She accompanied him, once again, to the hospital.

After he was healed, he started afresh at the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. He stayed clean for long enough to complete his education there. Afterwards, he went to Gusau, Zamfara State, to observe the mandatory National Youths Service Corps programme. He brought home a plastic table for her.

“That table you see behind you, he brought it along for me after his NYSC programme. I have resolved to never discard it. Everything he ever bought for me, I have cherished and kept very well,” she says.

Suleiman stayed clean for years. Long enough for his family to believe that the worst days were behind them.

Suleiman’s death

The day he died, there was nothing about his health or disposition that showed that something was wrong. In fact, the night before, as they sat together to celebrate his new appointment with the CBN, he had told her that he was at peace. That he was so happy that he was finding it impossible to sleep. And then he said a prayer that scared her.

“He said, ‘Ya Allah, if this new job is going to make me go back to my old life of drugs, I’d rather that you take my life.’”

People would later try to convince her that that prayer was his undoing.

The day after, on Nov. 19, 2017, when she rushed into the room to find him coughing out blood, she held him as they kept waiting for a car to arrive to get him to the hospital. He held tightly onto her and kept telling her that he was sorry.

“He said, ‘Mama, please I’m sorry, please forgive me.’”

It was not the first time he would have that kind of episode ever since he first came down with Tuberculosis, but as the car took him away to the hospital that day, with his siblings holding him, something in Maman Sani knew that she would never again see her son.

Suleiman died during the journey to the hospital.

They tried to hide it from her during the first few hours, she remembers. Her last child, who stayed home with her and already knew, took her phone from her.

“She took my phone from me just in case someone tried to call me to tell me. Ah, death, death is loud as a drum. And I said to her: my son is gone, right? You are trying to hide it from me right? Right? And I started crying. And crying. And crying.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter