A Walk Through Sex, Drugs, And Despair With Women In Kano

Women – sex workers, divorced women, students – in Kano, northwestern Nigeria, talk about the genesis of their drug addictions.

The road, flanked by several brothels, is brought alive by chattering and casual swearing from young people, the sound of people playing snooker, vehicles passing, and all the other signs of youth and life.

On the street, there is a robust gathering of women who left home in search of independence, and who have now found solace in drugs and sex. They live a life of dependence on both vices, which has in a way defeated the notion of finding independence, but it brings them euphoria and ecstasy and, for many, that is enough.

Some of them even have little pockets of accomplishments that aren’t products of their vices.

“Despite all my years on the streets, I’ve never had a child outside of wedlock,” Safiya* says, for example.

She draws a few drags from her cigarette, tilts her head up, then blows the smoke into the air. She is sitting on a thin slice of concrete, a cigarette in hand, and legs spread slightly apart.

She says it with her shoulders high up, her voice a little louder than usual, and it makes her friend, who is sitting next to her, look at her with wounded eyes. Later, the friend admits having a child outside of wedlock, conceived from her sex work. She says Safiya’s brag was intended to wound her. It creates a sour gap between them, but it only lasts for a few minutes. Later, they will share a cigarette, and all will be forgiven and forgotten.

Safiya

Safiya moves about with a small, fancy water bottle that she cradles softly. She admits it is not for storing water.

“It’s for codeine.”

She pours the cough syrup inside the water bottle for the purpose of disguise. A bottle of codeine is not an uncommon sight in the brothel where she works, nor is it an anomaly within the neighbourhood she lives in. Still, she prefers to pour it into the fancy bottle because it is easier to move around with, and more dignifying. It also enables her to have a larger quantity stored at any given time.

The cough syrup, which has become highly controlled as a result of it being heavily abused in Nigeria, has become expensive for the same reason. It went from being sold for around ₦700 to around ₦3,000. However, there are other variants, which are less expensive but give similar effects as codeine, and so sometimes drug addicts settle for them. Other times, they mix it with water or another kind of drink. Still, they are all mostly known by the umbrella name of ‘Codeine’.

According to a 2018 BBC Eye investigation, Kano is the centre of the epidemic of the drug. It is popular amongst drug addicts in Nigeria, and even though it is known to cause organ failure, it is an essential part of Safiya’s life, as are other kinds of drugs.

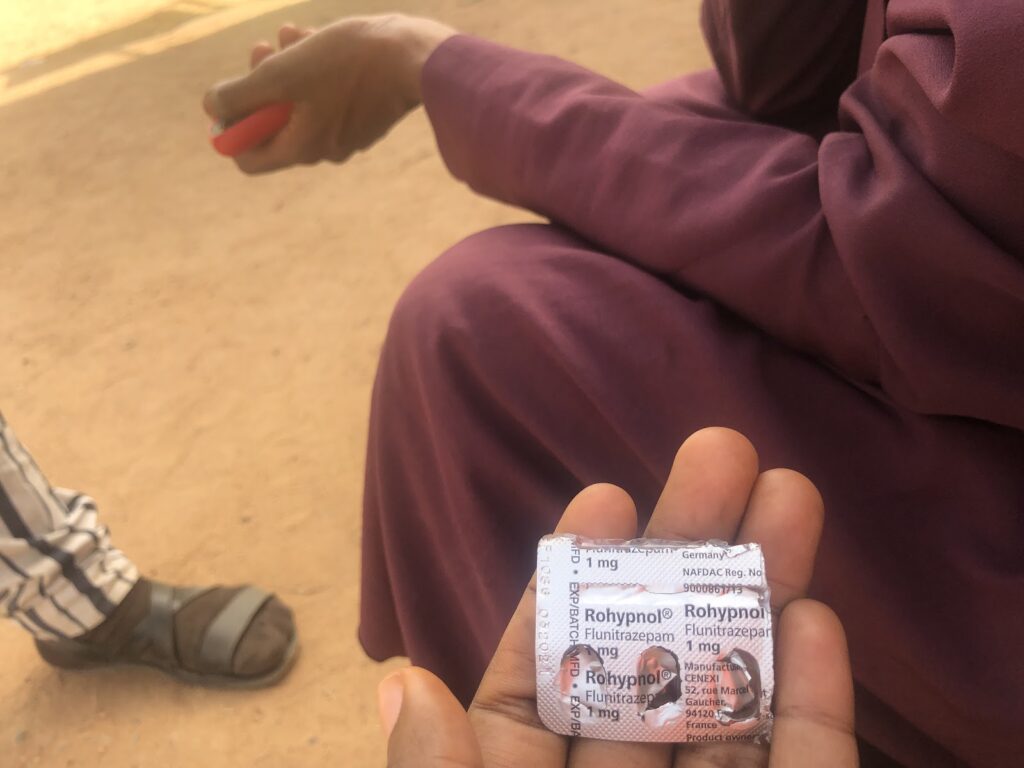

“When I woke up today, the first thing I did was smoke marijuana, and that was when I felt complete,” she says. “Then I took some Rohypnol pills, then another batch of marijuana, and then finally settled on cigarettes.”

Then, she knew she was ready to start her day.

She does not need to disguise or hide the cigarettes like she does the cough syrup, because it is very common and not illegal. Right now, she is sitting amongst five of her friends, and they each have partly smoked cigarettes in their hands.

For pills, however, she cannot have them in her purse, because her neighbourhood is one prone to constant raids by policemen and sometimes the notorious Islamic police force, Hisbah. She hides the pills in her clothing.

“It is true that police officers sometimes rape us when they arrest us for drugs and sex work. Heck, even Hisbah does,” she says.

“Did I hear someone say Hisbah?” her friend asks. “Hisbah once arrested me and when I was released, one of them gave me his phone number to hook up later.”

“Oh, yes. They won’t even arrest you if you’re not pretty, because they know what they are looking for,” Halima says. She talks about them with contempt and bitterness.

Her countenance relaxes when she switches back to talking about the drugs. Now, it is with mixed emotions; she seems elated, grateful even, that she has them to help her through life. But she also seems saddened that she needs them at all.

Safiya was once married. She has a daughter, too, whom she loves very much.

“She’s very pretty,” she says proudly. “Even prettier than me. She’s with my grandparents, and she is enrolled at a school.”

Her marriage had to end though she and her husband were very much in love. It became difficult and, later on, impossible to hold onto it, because her in-laws were “traditional people” and she was not. She explains that the pressure on her to conform was too much and she was unwilling to.

After the divorce, custody of her daughter was given to her. Before she switched lanes in life and became immersed in drugs and ‘street life’, she handed over her daughter to her parents in an effort to shield her from the negative influences, she says.

“God forbid that she knows this life,” she spits. “I am even trying to get my life in order now. Because I don’t want to die like this … There was a day that I sat down and took all the drugs and alcohol you can think of. Marijuana, cigarettes, Arizona, Rohypnol, three different kinds of alcohol, including McDowell. By the time I was done, I was completely wasted. I had a nasty headache. I did not know what to do with my life. I just sat down in the middle of the street and I was crying. I did not know what was wrong with me, but I was crying.”

After several years, she has now moved out of the neighbourhood and back to her grandmother’s house to live with her daughter. “I moved back just yesterday. I only came here today because of my business.”

She has started to sell second-hand clothing and other petty things. She gets them from the market and sells them within the neighbourhood. She has also enrolled at an adult education centre. “See, I even have my ID card with me.” She fishes inside her purse and retrieves her card which she then flashes. “When we finish this conversation now, I will go and get my national ID card too.”

After a while, she says again, “I really want to get my life in order,” and it seems more for herself than for her listener.

Halima

Halima* sits on the floor in an open corridor facing the roadside with her friends, eating Spaghetti and palm oil from a black nylon bag, and chicken from another bag. Her legs are spread wide apart, and she has no underwear on. “Sit well, you!” her friend urges. “It is showing.”

Halima cackles loudly and responds: “There is nothing to be ashamed of. A child came out of it once.” Still, she adjusts her sitting position by joining her legs.

When she is done eating, she picks her cigarette pack, removes one stick and lights it.

“You see Rohypnol? I take it because it makes me want to make love. And it makes my work easier. So I take about four pills daily,” she says.

“Codeine makes me sleep; that’s the only thing it’s good for. I take it because it helps me sleep at night after my day’s work.”

“I am not very much into drugs,” she says. “I only do codeine, marijuana, cigarettes.”

She admits she is heavily reliant on cigarettes.

“Honestly, I smoke more than one pack of cigarettes daily. Because there are twenty sticks in one pack and I smoke an average of 25 sticks per day.”

She agrees that it is detrimental to her health, even more so than all other drugs she takes. But it does not seem to worry her much.

Aisha

When Aisha* went into drugs, it was because she desperately wanted a way out of grief. She was 17, newly married, and had just lost her husband in a fatal motor accident.

“You have to understand, I also lost my mother at a very young age – I was five. I was filled with grief. I wanted to forget all my troubles.”

Her husband had also left her ₦8 million in inheritance. When many people venture into drugs, they begin with cigarettes, as it is more accessible and also not illegal.

Aisha began with cocaine.

As a result of its addictive nature, and how expensive it is, it took her no time to exhaust all the money left to her on drugs. And when her resources ran dry, she began to sell her properties to purchase more drugs. It was around then she realised her addiction had reached a level that was alarming. She started to find ways to restrict herself from the drug.

“Because I had spent upto ₦8 million on it, I knew it had gotten out of hand. The truth is that there is no drug that gives as much euphoria as cocaine does. It makes me forget my problems. But I later realised that it only makes me forget, it does not make the problems go away. Drugs only make me forget momentarily, or to feel good for a short time.”

Now she is 25 and set to get married in a few months.

“I am getting married soon, so I want to stop. Because as someone is growing up, the growth should reflect in their behaviour too.”

She also lives in the more polished part of town, and goes to school. After the conversation, she adjusts her hijab, tucks her tablet of Rohypnol in her purse and leaves for class.

On the other side of town, Halima and Safiya share a cigarette to mend their bruised relationship.

*Names with asterisks were changed to protect the identity of persons interviewed.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter