Nigeria’s Floods Leave A Trail Of Ruin And Heartbreak — Photo Essay (II)

Houses levelled in the dozens, families separated, livelihoods lost. This year’s flooding disaster has spread devastation across Bauchi, Northeast Nigeria. In the second of three photo essays for HumAngle, Abubakar Sadiq Mustapha visited the communities worst affected.

One after another, passengers alighted from their cars. Two men in their mid-twenties, Mohammed and Tasihu, emerged from a boat to direct the drivers. They had deliberately parked the boat in the middle of the road to prevent them from passing through a route that was no longer navigable.

One car, whose driver might have lost control, had plunged into the ditch created by the flood. Metres from the road lay the marshy alternative path, where cars could get stuck if they were too heavy. So, passengers had to walk until their cars returned to the comfort of a tarred road.

“We show people where to follow, considering the road has been cut off. So, anyone who comes and doesn’t know the way, we guide them to cross over,” Mohammed Haris, 25, a boatman from the Zaki area of Bauchi, said as he removed a fish from a bow.

“When the water broke and took over the road, no single car or bike coming from Azare to Katagum could pass. So, Tasihu and I brought our canoe and help people cross. We charge ₦500 ($1.1) per person and sometimes ₦200, depending on how full the boat is.”

Mohammed recalled that a young driver recently died on the spot. He had fallen into the trench and broken his neck and leg. He passed away before he could be taken to a hospital.

“We do not know which action the government will take on the issue. We are waiting.”

Lost lives and farms

Recent floods that swept across many parts of Nigeria turned about half of Tashena, a community in Zaki, into a river. Farms were buried in the flowing water. Houses collapsed on their dwellers, and according to locals, this killed at least 10 people. Families had to seek refuge in schools, tents, and huts as they waited for the water to recede, so they could start rebuilding.

“My crops were almost ready and I was expecting a bumpy harvest. Then one morning, I woke up to a farm swallowed by water. All my millet, corn, beans, sesame, and hard work are gone. I know this is a test from Allah, but it is sad. All our houses have collapsed, and many of our people are in schools. But my family is in a tent I built,” said Abubakar Sule, 26, a farmer and butcher.

“I lost a family member. When the water overpowered her room, it fell on her. We lost about 15 people in our community to the flood. We are all sad, but we pray Allah comforts us.”

The crossing to Tabak, a small fishing community in Zaki began in a manually-propelled boat made of wood. Before the flood, boats were not needed to make this trip as the river was either shallow or non-existent, depending on the season. Now, as it overflowed its banks, it killed the dreams of many residents, rendering farm owners hungry, house owners homeless, and families separated.

“We built sandbag walls, yet the flood came and entered our farm where we planted rice, corn, and millet,” said Digirine, 31, a farmer and tailor in the community.

“Usually, after the harvest, we used to realise 50 bags of beans, 100 bags of millet, and 300 bags of rice. Now, I am a thing of pity with no single harvest. That is why you see me with a sewing machine. I have returned to my old business of sewing to be able to get food for my family.”

Tabak has lost lives and properties to flooding before, but this is the worst the community has experienced. They say the government has paid little attention to them.

“We have been experiencing flooding every year. But in a hundred years, we haven’t seen what we saw in this flood. Farms, houses, cattle, and sheep went with the water. What we want is for the government to know our condition even though we are tired of writing to them. Every time, they ask us to give a statement and in the end, we don’t see anything. We have stopped giving statements to the government, but I feel through the media, we will be heard. Three of our people were submerged and lost their lives before we could take a canoe to rescue them and a lot of people’s properties went in the water. Our people need help.”

– Yunusa Wakili, Sarkin of Tabak

Sarkin Ruwa Ahmed, a fisherman and the man in charge of the community’s rivers, has lived in Tabak since his birth 60 years ago and says he is witnessing this level of flooding for the first time.

“The flood left us without rice, millet, corn, tomatoes, and peppers. If we must eat, we would have to buy from other communities not affected by the flood. But the prices are too expensive for us and the government did nothing about it. You can’t access Tabak until you use a canoe. I had to buy the canoe to ease the movement of people and services.”

Some silver lining?

The roads in Adabda, Meleri, and Ariya linking Azare to Katagum in the Zaki area of Bauchi have been cut off. This left travellers stranded in the early days of the flooding as transport fares doubled. Lush rice fields, houses, schools, and football pitches by the roadside were all submerged. Commercial activities were disrupted while electric poles collapsed, disconnecting the communities from the national power grid.

Meanwhile, at Anguwan Gabas in Katagum, as the water receded, it left behind many fishes. Fishermen and children spent days poking around with their nets, hooks, and calabashes.

“This is not a river,” stressed Muhammad Mamman, 53, a farmer and fisherman.

“Whenever it floods and the water goes back, it settles here and we fish. We cannot say we are not happy with the flood. We are not happy on one end, but in some cases, we are happy about it. During the dry season farming, it benefits. But during the rainy seasons, there are no benefits. The flood usually eats up our farm produce and our houses. You can see how it has destroyed all these houses. There is no farm that it did not destroy. Now you see all these are farmlands that have become useless. The loss from my two farms and house can amount to ₦3 million ($6,800), but I am happy that I can fish in this pool. At least my family will get something to eat.”

Some of the residents of Anguwan Gabas had to seek shelter in schools and with relatives after the flood swept away their homes.

“I am a farmer and fisherman. When the flood took over my home and farm, I was confused because I had spent so much money on the farm and in building the house, approximately three million naira. I didn’t know where to start,” Bala Sule, 50, told HumAngle. “Presently, my family is at Nassarawa Primary School seeking shelter. But I am here to catch fish so that I can sell and get some money. I hope the government will come to our aid.”

Homelessness, separated families

In Tabak, many people are separated from their families because the flood swept away their homes. Some women who married in Tabak but are from other communities have joined their families. Some sleep in groups outside their ruined rooms. Some have sought shelter in schools. And a few who can afford to rebuild have started. For many, life may never return to how it was.

“The flood first destroyed our neighbour’s house. Then in an instant, our rooms became flat, and everything was gone. I didn’t believe it. I thought it was a dream. When it happened, my husband asked me and my co-wife to return to our fathers’ houses in another community, but I didn’t want to leave my house. I didn’t want to miss him. I stayed and my co-wife did and at night, we sleep outside our ruined rooms with a group of other women,” Hajara Haruna, 36, told HumAngle.

“We were sleeping when the front of my house fell. I was startled, and then at dawn, after the morning’s prayer, the whole of my first wife’s room fell. After that, more rooms went down. Two of my wives ran to their villages, leaving the children with me. I do everything for myself; I just finished cooking,” Abubakar Awwalu, 30, a farmer, said.

Dozens of homes destroyed

In one area with over 100 houses in the Sabakuwa community of Zaki, no house remained standing after the flood. The people had done their best to push back the water by building walls of sandbags, but it was futile.

“The flood ate five of my farms and left only one for me. I spent more than ₦600,000 ($1,351) cultivating them. Before the flood broke into the town, the government had sent 500 sacks for us to build sandbag walls. Even after that, the water still found its way. We pray the government can come to our aid; most of the affected people can’t afford to rebuild,” pleaded Umar Muhammad, 48, a farmer and fish seller in Sabakuwa.

“The water came and sent us out of our house in the middle of the night. I don’t even know where my wife and children are sleeping. Every day they meet me at our ruined house, where I am rebuilding and collect money for food. As for my farm, after applying 10 bags of fertiliser, then the water came and took away everything. I have spent about one million naira on cultivating the farm and there is no single person from the government who has come to see our situation. It is too sad,” Abubakar Idris, 32, a farmer in Sabakuwa, confirmed.

“The flood submerged more than five hundred farms in Sabakuwa and countless homes. Ten hectares of my rice, 20 hectares of my millet field, and three other fields have all been submerged. There is nothing we could take out of these fields. I am not happy about what happened to me and my people, but we have accepted it as fate and pray to Allah for better days,” Bulama Abdullah, the traditional head of Sabakuwa, said.

Temporary shelter

The classrooms in Kore Primary School in Kore, an area in the Gamawa Local Government Area of Bauchi, became a refuge for many women and children displaced by the floods. The classrooms had only mats, mosquito nets, and some of the properties the people could escape with.

“On a Tuesday, God brought the flood to our community, and we suffered to escape the water alive because most of us can’t swim,” said Hadiza, 30, an IDP at the school.

“Presently, there is no single house in our area in Kore that survived the flood; all have been washed away. What is left is debris. We have spent 40 days already in this camp and it is not comfortable. Some of us have six children, others five and more. But it is better than sleeping outside. A few days ago, the government brought us millet and corn, one mudu for each person. It is not enough but we are grateful. We pray this test from Allah will be a blessing upon us all.”

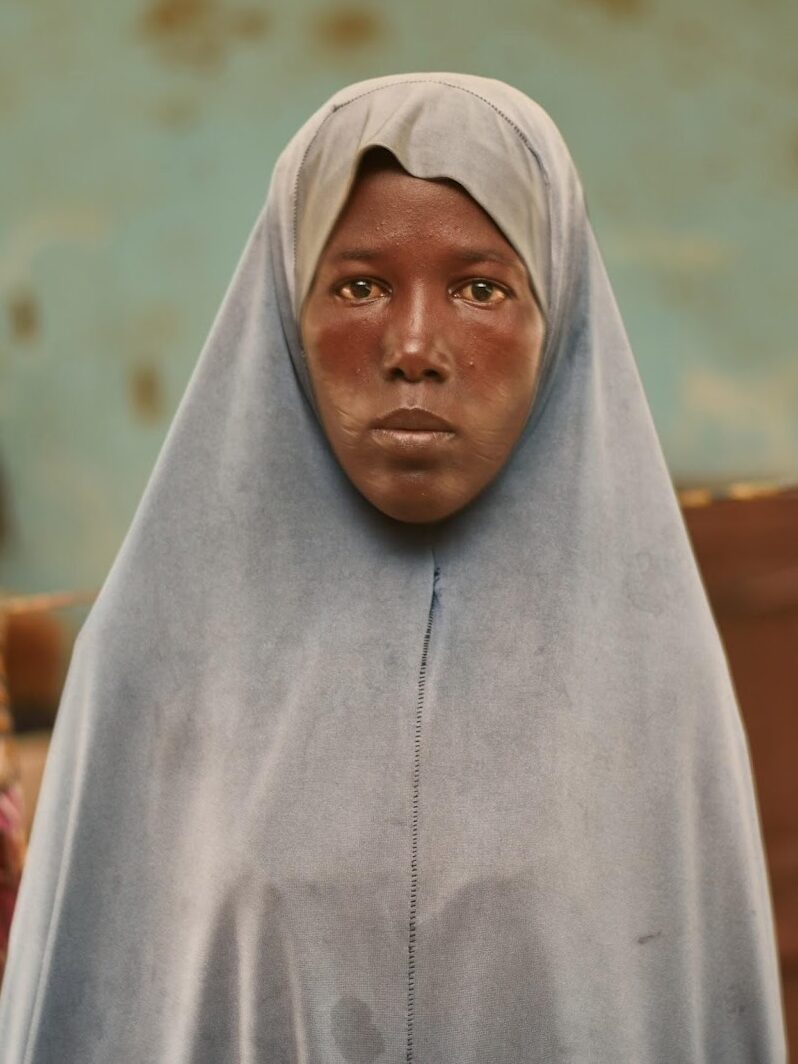

Salamatu

A mother and wife seeking shelter at Kore Primary School, Bauchi state.

Maryam Ali

Lives inside a class at Kore Primary School with her daughter.

A few people in the community have started rebuilding and hope their families in IDP camps and living with relatives will join them soon.

One of them is 47-year-old Ali Kore, whose family are at the primary school.

“We are building tents and huts to bring them back because the children in the community need to return to school. We do not even have what to eat. We have to hustle hard for it every day. We have lost everything to the water,” he said.

In the midst of great loss and neglect from the government, the people in these communities remain resilient and have one thing in common: their hope for a better tomorrow.

Photography by Abubakar Sadiq Mustapha.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter