545 Days (2): Surviving Captivity

Part two of HumAngle’s serialisation of the story of Jummai Inuwa and her companions, kidnapped and held by the Islamic State in West Africa Province. Read part one here

Jummai has been seized from a taxi taking her from her home village back to Maiduguri, Northeast Nigeria, where she works for a non-governmental organisation. With a group of other abductees, she is being moved deeper into the countryside, away from safety and toward the terrorists’ camp…

They spent three days moving across-country, following tracks and trails that crisscrossed the land. They were handed over by their kidnappers to another group of armed men, who led them along the route to another handover, who would hand them on again.

At one point, even their captors found it difficult to navigate their way to their destination. They had to rely on the GPRS device they were using, and when the network dropped, they had to ask some herders they encountered for directions.

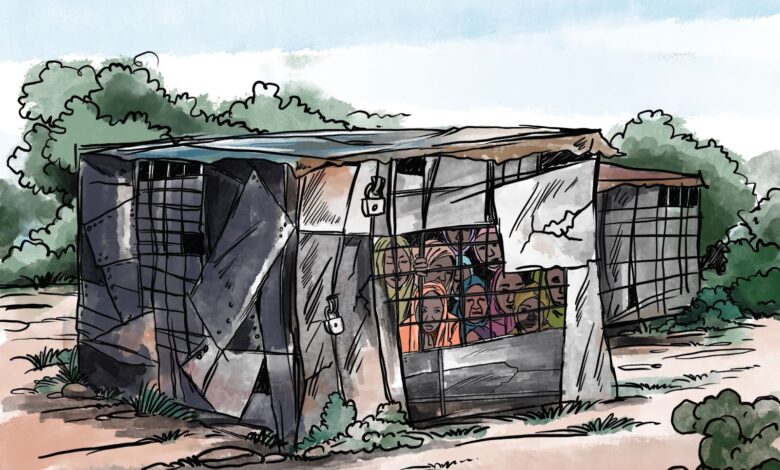

“It was a terrible experience,” said Jummai. On the third day, they arrived at what she called “Tapkin-Chadi,” Lake Chad in Hausa. They were marched into the waters and waded knee deep, surrounded by tall grass, toward the camp where they would be kept. They learned the area around the camp was called Maikoko by the terrorists.

Fighters lived on this island, with their wives and families, and there were other captives there too, hundreds of them.

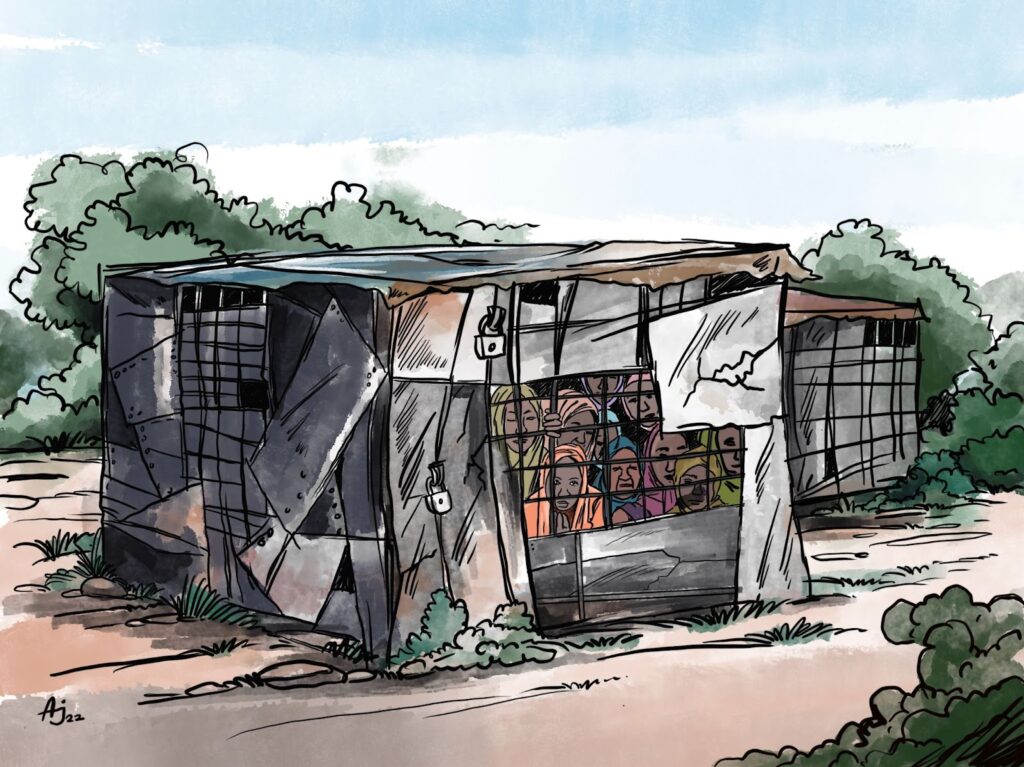

All the prisoners were held in tiny shacks made from corrugated sheet metal, salvaged from wrecked houses in the villages they had sacked. These were referred to by Jummai’s captors as Sijjins, an Arabic word meaning cell. They were windowless and hot as ovens during the day. Living in them was very tough.

“We battle with heat, then hope not to be stung or bitten by reptiles like snakes and crawling insects like scorpions which usually torment us day and night,” she said.

“Sometimes the wind blew down the huts, and no one came to fix them for us. We had to spend days in the rain and sun. And when they see us in such conditions, they would be laughing and mocking us.”

First attempt to escape

After three days as a prisoner, Jummai said she and two other abductees, a man and a woman, attempted an escape. They tried to find the way they had arrived at the island, but wherever they got to the water’s edge, they found it too deep to wade anywhere.

They kept looking. They ran one way, then another, but found their path was blocked in every direction. “The more you go around, you will end up where you started. It was confusing how we could not find our way out. Everywhere was surrounded by water,” she said.

The landscape of Lake Chad is a maze of water and sandy “islands”, the tops of sand bars that break the water’s surface. These islands are fringed with tall water-grasses and reeds, which stop anyone seeing very far. Much of the water is choked with vegetation, like floating water lettuce and papyrus grasses. Pondweed and eelgrass, tangle with ambatch, or Shuwa trees. The ground might appear solid, but anyone walking into the hippo grass would fall through the matted reeds, into the water.

While on their way to Maikoko, there were few places where they had to pass through the water, and they waded only knee deep. But she could not remember the way they had come, “the waters were not that deep compared to the waters we saw when we were trying to escape,” she said.

She says they were walking around the labyrinth of sandbars and reeds for hours before they decided they had no choice but to give up. “After trying all night to find our way through the safe portion of the water without luck, as we only went in circles and ended up where we started, we had to give up and surrender to the terrorists.”

“We made that decision to reduce the punishment that we might face should they find out in the morning that we escaped, and they later caught us.”

They approached some guards and told them they had gone out early to find some herbs they could use to treat the sores on their legs.

“They did not believe us as they had to flog us from that point till we got to our Sijjin. Their whip was made from camel skin and left deep scars on my back to date. It was hell. I was bleeding, my legs were full of sores, and they became septic due to hours of walking in the water.”

Jummai and her two fellow abductees arrived back at the Sijjin, and had to face a disciplinary panel.

“The other lady had to confess by shifting the blame on me out of fear. So, I was seriously flogged,” she said.

“Two of them placed the nozzles of their gun on the sides of my forehead and fired simultaneously. I nearly passed out as I fell,” the noise of the shots permanently damaged her hearing.

The man who had attempted to escape was able to make it back to his cell unnoticed. The guards had been distracted by the women.

The other lady, named Faina, from Adamawa state, is still in captivity, Jummai believes. She was separated and taken to a camp on the Dikwa-Marte axis called Tumbuma.

Jummai suffered wounds to her feet during the escape attempt, and they became infected. She thinks she could have lost two of her toes to the sores, were it not for the rudimentary action she took. “They did not give us any medication; so, we had to use salt and warm water daily to soothe it and prevent the wounds from worsening. It later healed.”

It was clear she must give up on escaping, for now. It was practically impossible to do so. And should she attempt another episode, it might cost her more than the punishments she received during the first one.

Executions

Jummai decided she would have to steel herself, to use all of her guile and intelligence to work out the best way to survive. She used every opportunity to learn more about who had taken her captive, and how to tailor her behaviour to what they wanted. She must do this without allowing them to take away her inner resolve to live, to survive, and perhaps, one day, to get out.

When she was seized by the roadside she found out from the driver, Musa, the men taking her were from ISWAP, not the Shekau-led Boko Haram. This gave her a slight edge of confidence.

“I felt relieved that they would not kill us, at least not immediately.”

She expected to be either enslaved, sold out for marriage, or traded for a ransom. But when she arrived at the island, she discovered her captors also killed women.

Any female security personnel could expect the worst. Or if a woman attacked a fighter, or tried to kill a man, they would also be executed.

There was another reason for summary killing: If a woman was found to be HIV positive.

“Yes, before a woman is given out as a slave to their masters or sold out, they had to conduct tests, especially for HIV, to know one’s status.” They ran as many as three tests on each woman they seized, so they could be sure of the diagnosis, a process that suggests some level of sophistication in their capability to conduct hundreds of blood tests.

“A woman is certified healthy to be enslaved as a sexual partner to their masters or before they are sold out. But if one is found to be HIV-positive, they will kill such a person at once.”

“They say you are of no use, and you may have gotten it through waywardness.” The death sentence for being HIV-positive is not limited to abductees; members are condemned to death if the leadership finds out they are infected with HIV.

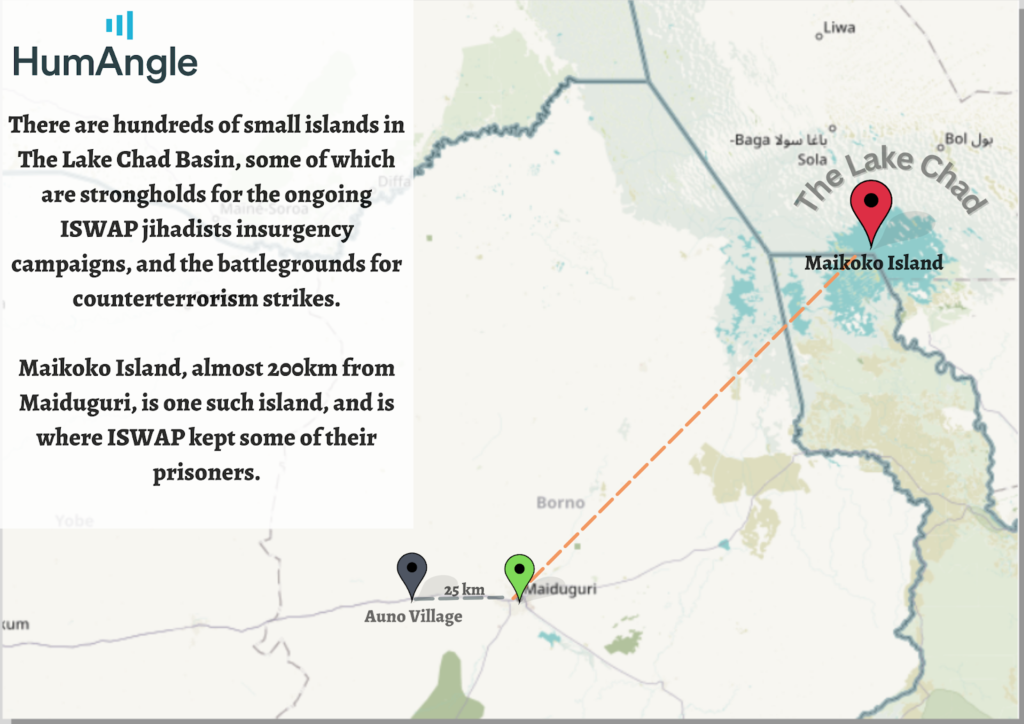

The executions are conducted in front of everyone in the camp. They called out their names one after the other and made them sit down on the floor with their body and face covered by a Jilbab. Their crimes were read out, and then they would say they had found them guilty.

“After that, the gunmen would appear behind the condemned, each aiming at a target, and then they would fire at them.”

Some of the women were pregnant, or nursing mothers. Jummai said in some cases she saw their fighter husbands watching the execution of their wives, and never saw even a flash of bitterness.

Hardened and degraded

Jummai said she used to be emotionally disturbed each time she watched the public execution of offenders, but over time she became hardened to the taking of innocent lives.

She had to become hardened to many things. The process of dehumanisation was very thorough; it began with forcing her to dig her own grave.

“Each time a jet fighter comes shooting, that is where we normally run to. And if one is hit while inside the hole, they don’t need to bother bringing you out; rather, they would simply push the sand over the body and the person is buried. I dug what they called my own grave. They see us as walking corpses.”

They kept their prisoners, about 500 on this particular island, in inhumane conditions to further dehumanise them.

They were starved, she said. “Sometimes we go days without food. Sometimes one had food and everything but you don’t have water to cook it. Sometimes you have food and water but no fire to cook. You dare not go out of the prison yard without permission. We were under locks and keys in Sijjin. At one point we were under lockdown for five straight months.”

There was little opportunity to wash, and there were no sanitary pads for the female prisoners during their menstrual cycle. “Sometimes I had to practically spend like two straight days in the toilet to let the blood flow out. Sometimes when the flow reduces its rush we use our veils as padding.”

Little by little she got to know some of the “slave maids”, captives forced to attend the wives and families of the fighters. “They had access to things like sanitary pads, they started helping us with the locally improvised pads. Or they give us rags from their houses to use. The women also helped us with things like salt and seasoning cubes by secretly bringing them into our Sijjin.

But this brought up another problem, the problem of who could she trust, and what effect trust -and hope- could have on their minds during captivity.

Trust

“You can’t afford to trust everyone in the bush. Even a fellow victim can implicate you or divulge what you have discussed with him or her before he later radicalises and puts you in danger.” The implications could be deadly. “Yes, someone did that and two people got killed.”

Jummai said she had to fight to avoid being married to any of them.

Many of the girls who later agreed to marry their captors did not do so under duress but rather they were brainwashed and cajoled into doing so.

“The worse thing that could happen to a girl or a woman is being turned into a sex slave.” She says. Many of those who were married were incapable of resisting.

“Even some abducted housewives gave in because these guys, perhaps, are showing even better caring than what their spouses used to accord them. But they don’t force you into marriage unless you are condemned as a slave and sold out to a commander or anyone who can afford to pay.”

They always made efforts to retain control. They took time to know many things about their captives, down to the shape of their footprints. “And they have very sensitive ears; they can pick words spoken to somebody even from half a kilometre away,” Jummai remembers.

Jummai was fortunate that her phone handset and laptop were left in her bag in the car she was travelling in when she was taken captive. They went through people’s phones forensically analysing them, downloading chats and all social media information to use against them. Jummai had hidden the fact that she was educated, lied to them about how she was already married and had children and added some years to her age.

There was a particular lady who married one of the terrorists. The lady told Jummai that she was in real love with her initial ISWAP husband. He had shown her love and affection, in the manner her husband at home did not. She said the man was a good lover. But she was shocked when this new husband passed her on to another man, without her having any say in the matter.

Marriage is very important to the men, their particular vision of it anyway. Jummai said they hold special courts to resolve marriage disputes, and that some of the women captives are traded between the men, or sold back to their families for ransom as they please.

Jummai tried especially hard to avoid being married. She believes it was her age that saved her. In her cell there were 12 women, all were given HIV tests, “After two weeks or so, they brought in my picture to confirm if I was the person in the photograph, and I confirmed so.” After that nothing more was said about marriage. “That was how I was saved from forced marriage. Every other woman was given out and taken to different locations. I and a Muslim woman were the only ones left behind in our Sijjin at that time.”

Hope

There was another way they cruelly manipulated their captives, by using hope.

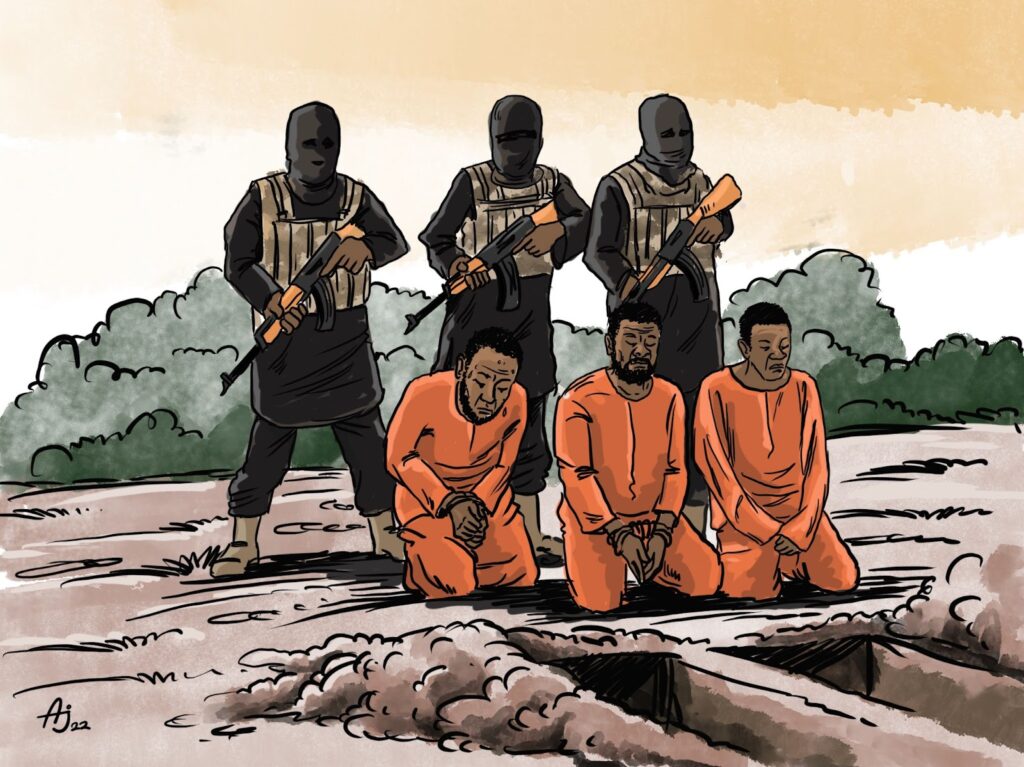

She remembered how some officers of the Nigerian Immigration Service were executed.

“They gave them false hope that they would be released to go home,” Jumai said. “They took them on a tour of the water in a speed boat for some time and then later returned them to the Island, and even offered them soft drinks and nice things to eat. They then asked them to put on some uniform – overall orange-coloured clothing – which was a sign that they were about to die.”

The men were forced to dig their own graves then the Sarkin Yanka (meaning slaughter Chief, in Hausa) and his men set up a video to record the men being killed, one by one. “They would ask some of the abductees, especially the men, to remove the orange gown and hang it somewhere as a reminder that anyone could be the next victim.”

In some cases, they asked for a ransom payment, but negotiation was not a sure sign that everything would be well. “If there were unnecessary delays or misbehaviour on the part of the negotiator or even the victim, they bullshit the ransom and they would go ahead and execute the person. They don’t entertain one being rude.”

But after a time, it wasn’t seeing people killed that was hard, the hardest part was seeing other people go free.

Jummai said she had in her over 18 months of stay in captivity seen many persons who were lucky to be freed. Some don’t even stay for a month.

“It was not easy because I saw like 36 incidents of the negotiated release of captives who were freed in my presence, but the last one was terrible for me,” she recalled.

“I felt terrible because I was tired, fed up, though I was strong, I felt hopeless, rejected, worthless, humiliated and valueless. Yet I was strong for myself and my colleagues.”

It was on that day when one of the three MSF workers, a woman, who was abducted at Fotokol was about to be freed after they had agreed on the ransom. “I broke down and cried. I cried because there I was battling to free myself after the earlier negotiation failed. After all, they were demanding N50 million which I know no member of my entire lineage can afford to pay. I cried, I went wild and scattered everywhere.

It took the intervention of several people to subdue Jummai “and my colleagues told them my mood had to do with my health.”

Jummai survived by learning what she could about her captors and hardening herself against their manipulations and the terrors of captivity.

She talks bluntly about what it has done to her: “I am sorry, but I no longer see life being taken as something to worry about; it is like a normal way of life for me out there in the jungle. Even now, no amount of blood moves me. I have learnt to cope with a lot of things. For example, I learnt how to administer an IV to myself if I feel sick. I don’t fear death or anything that could cause one to die. I see death as a very normal thing in life.”

In Part 3 we will learn how she won the trust of some other captives and used what she had learned to escape to freedom.

Read the other parts below:

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter