Hunger, Starvation Excluding Borno IDPs From Ramadan Fast

Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in Maiduguri, Borno State, Northeast Nigeria, narrate their plight fasting in the Islamic month of Ramadan after the state government imposed a ban on food distribution by aid organisations.

Once, Karu Bulama did not have a proper meal to break her Ramadan fast for three days. When the call to prayer is announced at the end of each day’s fast, there would be no food for her family to eat.

Ramadan—the ninth month of the Muslim calendar—usually brings glad tidings to Muslim faithful globally, as it is the time of the year when many refrain from eating and drinking as an act of worship. Throughout the month, the fasting begins from dawn, and is broken at sunset.

“I was only given half a cup of Kunu (corn drink) in those three days. I felt very frustrated. I cried so much. I asked how it would be enough but people said I should drink it, at least, it was better than nothing,” Karu says.

Karu experienced this ordeal in 2014 when she left her home in Budumiri, a small town within Damboa Local Government Area (LGA) of Borno State, Northeast Nigeria, during the peak of insurgency in the region, and sought refuge in an Internally Displaced Persons Camp (IDP) at Bama.

The camp, which is a cluster of tarpaulin tents, is set up within the compound of a General Hospital in Bama LGA of Borno, which was destroyed by the insurgents. Thousands of IDPs who still live there have, through the years, experienced extreme food crises and severe malnutrition.

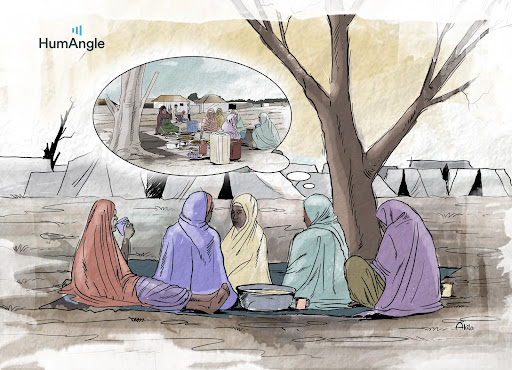

Currently, Karu Bulama is in Dalori II camp in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno, where it is relatively safe. Yet, this year’s Ramadan causes her to remember the hunger and hopelessness she felt while fasting in the Bama camp.

In the six years since Karu arrived at Dalori II, the World Food Programme (WFP) donated food to them, including giving them an e-voucher that entitled them to N17,500 cash monthly. However, in Dec. 2021, Babagana Zulum, the Borno State governor announced a ban on the distribution of food and non-food items to IDPs whom the state is currently in the process of resettling back to their original or new communities.

This was when their affinity with starvation returned.

Fasting without relief materials

There are approximately 941,551 IDPs residing in camps and similar settings in Borno. According to the Northeast Nigeria Displacement Report Round 36 released in May 2021, an increase of 27,240 persons were present compared to the previous round.

Though the ban on food distribution was announced in Dec. 2021, IDPs in Dalori II had stopped receiving relief materials from organisations since October. This is because the government considered their camp already closed.

Another IDP, Amina Musa, 80, traces the beginning of her misery to ten days after the previous Ramadan. “Since the last Ramadan, they [the state government] told us we will be taken back to our communities but that has not happened yet. The governor also said we cannot work until he gives us the go-ahead and they have not allowed those donating food to help. How can we survive? He should at least leave those that can to work.”

In the face of extreme hunger, others have disregarded the governor’s orders and found work to sustain themselves and their household. A’issa Kawo wakes up in the morning to work on an onion farm. “I go there every day to clear and weed the farm, and I get paid N400. That is what I use to buy some food and when I get back home I make Kunu. That is what we eat when we break our fast, me and my two children.”

During the day, A’issa’s children, who do not fast, get food by begging; they are not alone as many IDPs rely on alms despite the ban on street begging in Maiduguri.

Fasting before being displaced

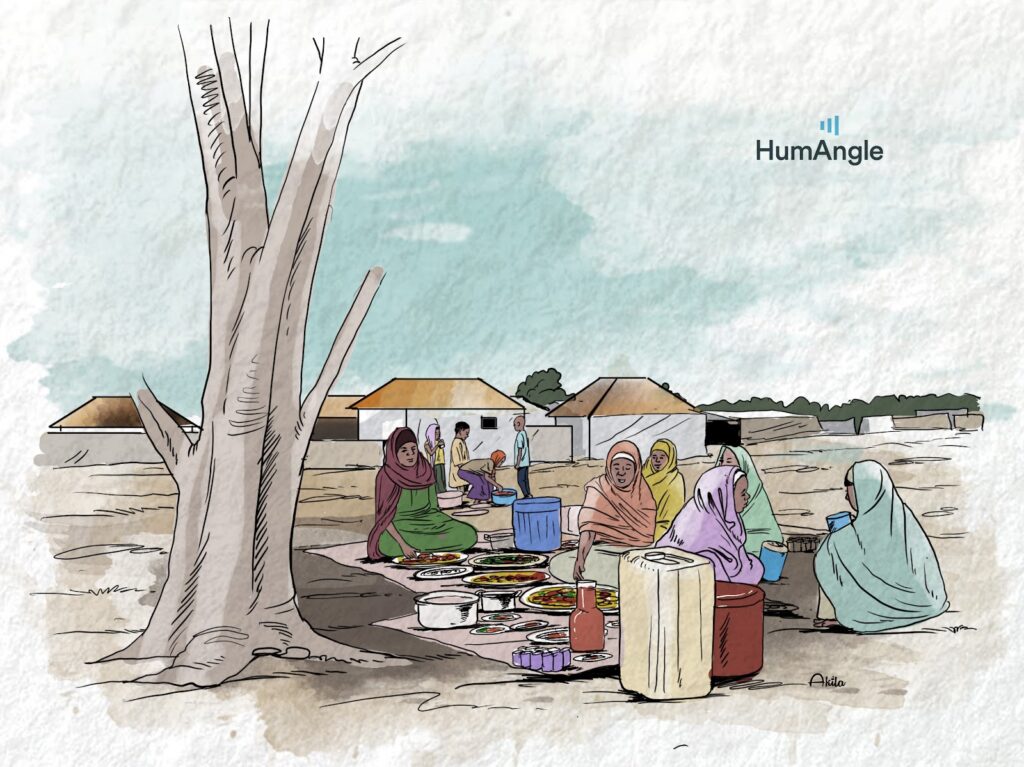

Ramadan is usually a bittersweet memory for Karu Bulama and many IDPs in Dalori II in Maiduguri. Karu recalls that, “In Budumiri, we were always delighted with the coming of this holy month. By this time, we would have stocked up our silos with farm produce, we would be fasting and performing our Ibadah [worship] in peace, we would help each other, and even give alms to those who did not have. That was how we were living.”

Amina Musa also has a similar memory of Ramadan in Kodo Gambobe, Borno state, where she is from. “We used to eat fresh fish, meat, rice and … fruits. I never worked for food, I got everything I wanted easily. We usually break our fast together with my children and grandchildren, but all this has become a distant memory.”

In 2014, when the insurgency became grim and life-threatening, it was Amina who advised her family to abandon their home and seek refuge in a safer place. They first went to Bama IDP where, when the fasting month for that year commenced, they did not even know.

“It was after two days into the fasting we were informed and because there was no food, we all fell sick. That was when we were transferred to Dalori II.”

Ramadan fast is obligatory but some have not been fasting

In Islam, fasting during the month of Ramadan is obligatory as it is among the five pillars of faith that must be fulfilled. It is also the period where Muslim faithful seek a richer perception of God, as, apart from abstaining from drinking and eating, one is supposed to refrain from acts that are deemed unholy.

Zahra Bukar, a mother of seven—also living in the camp—who has not been fasting claimed that many women still engage in sex for survival to get food or money for food. Last year, HumAngle investigated how women and girls in the camp are forced to go into prostitution, or are sexually assaulted by camp officials in order to get food items or money.

“It is still happening till today. Women go out and spend the night with men for money, sometimes they earn up to N5,000. That is what they use to buy the food they eat when they break their fast.”

Zahra believes that IDPs who are too old to beg, and too frail to work are the most disadvantaged of the bunch. Although Islam provides exemptions for the sick and elderly, the lack of food still puts them in the same predicament

Maryam (not real name) is another woman in the camp who has also not been fasting. “We have not taken the fast at all. It has been twenty-something days of Ramadan now and we have not done even one.”

She claimed that she and other women had only arrived at Dalori II camp around April 19, 2022. Maryam added that even during her stay in the forest–which suggests that she was in a Boko Haram enclave–she was not able to fast due to the type of food she was given, which she described as bad and tasteless. “We really suffered when we were in the forest. There too we did not fast, here too we have not been fasting. We are just facing hardship wherever we go,” she said.

As hunger allows her no choice, Maryam admits that though her situation in the forest was horrid, nothing had prepared her for the starvation she currently experiences in the camp. “The food in the forest was not good but it was better than sleeping with hunger. It was better to be with them [terrorists] than to stay here.”

Several calls placed to Isa Gusau, the media aide to Borno State governor were not answered. He has also not responded to a text asking for a comment on the issue.

Resettled IDPs have it worse

One of the few things IDPs can be assured of is that many unexpected things will come their way. However, being ordered back to their communities without the guarantee of safety was unexpected.

Borno State is currently home to 75 per cent of all IDPs in Northeast Nigeria. The fact that their numbers in Borno has increased with over 25,000 individuals in the course of only two months could be an indicator of continued insecurity and increased mobility in the state.

The authorities have given various reasons for their decision to resettle IDPs. It ranged from the prevalence of early child marriage, prostitution, drug abuse, and thuggery at the camps; growing aid dependency and ‘entitlement complex’ among IDPs; the need to build resilience; and the return of ‘relative peace’ to various communities.

However, Gujja Ibrahim, who has already been resettled into the Shuwari resettlement site in neighbouring Jere LGA, told HumAngle that when it came to hunger and starvation, they were having it much worse.

Although IDPs still in Maiduguri face their own type of adversities, many of them are, at least, hired to work on farms or provide manual labour which often pays daily wages.

Some of the skilled ones run small-scale businesses such as tailoring and cap-knitting, and have access to residents rich enough to patronise them. In the resettled communities, these opportunities are absent.

Gujja recalled that at Gidan Taki camp, where she used to be before she was resettled, she had a small okra farm, and also offered her services to other farm owners who either paid her or rewarded her with grains. She was not making much but at least she was independent.

Although the state government claimed it gave N100,000 to men and N50,000 to women to help them adjust to life outside the camps, Gujja and others maintain that they got only N20,000 upon leaving the camps. Also, because many resettled IDPs are not familiar with their new surroundings, getting farmlands remains difficult.

A recent satellite data analysis from HumAngle revealed that the communities are exposed to terror attacks and occupation, while resettled persons also struggle to adapt to the difficult terrains.

As the holy month is quickly coming to an end, the women in Dalori II remain desperate for help. “Even if we get to fast for just two days, it’ll be worth it,” Zahra Bukar said. “We are begging the government to please give us food items so we can also fast this month.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter