Benue IDPs: Worry Over Survival Limits Hope For Better Future

“When there is life, there is hope,” the popular saying goes, but IDPs in Tse Yandev camp are saying, “when there is food, we can hope.” The sad realities foisted upon them by the conflict has robbed them of their homes, dreams, and importantly, hope.

When HumAngle meets Isaac, he is sitting pensively and staring at the children running around in the camp, located in the North Bank area of Makurdi, Benue State, North-central Nigeria. Occasionally, he would fold and unfold his hands, letting out long, drawn-out sighs.

Across the camp, his demeanor was replicated as men trooped in and out to either try to find something to do, or sitting down to sigh and shake their heads.

Everyday, the average human being wakes up and pushes through the day, in hope that as they work, they inch closer to the futures they want or desire. This hope has served as a major motivation for life across board – the hope for a better life and the lingering assurance that it is possible. Displaced people in Tse Yandev camp are so worried about surviving each day that they hardly have space to hope for the future.

Things were not always this way, at least for the majority, who like Isaac Ornunga had all they needed and could dream of better futures for their children. It took a while for him to escape with his family as he refused to leave all he knew behind, hoping that a miracle would happen and the conflict would stop.

“We came here because of the crisis. It got too bad especially in 2014 and we had to run away. We did not want to leave before but it got worse. First, our farmlands were destroyed and we were trying to manage around our houses. One day, my brother dug yams out that he wanted to sell. The buyers were already told that the yams were ready. When they came to the farm, everything had been destroyed,” he narrated.

“I feel very bad because I am a hardworking person who works with my hands to eat. I don’t depend on anybody. But now, except they bring something for us, I can’t feed my family. I now wait for people before I eat or I go and do menial jobs. I want to go back to the way things were before, in my village.”

Isaac’s pain is exacerbated by his inability to not only feed his family, but also enrol his children in school. He has three children, two are toddlers but one is old enough to begin school. Yet, there are no schools available around for free nor does he have money to enroll his child in one. He told HumAngle that the uncertainty of their future scares him but he would like to at least feed them first, for now.

Hope is a four letter word, hunger isn’t

Metaphorically, it is as though the number of words in hunger and its arrangement is a tell-tale sign of its difficulty as a state of being, for a person. Often, the shorter word, hope, serves as a placebo. It is the job of the camp leader, Yiev Geebe Gabriel, to try to provide this, keep the place running, and give the people reasons to look forward to another day.

When HumAngle spoke with the IDPs, they were appreciative of his leadership. One of them, Felicia Bako, who was severely butchered during an attack, said, “everyday, we thank God for our camp leader. Even if the food is not enough, he makes sure it goes round.”

Yet, as leadership weighs heavily on his shoulders, Gabriel fights his own battles and struggles to maintain hope himself. For him, survival has gone beyond his family. He has been appointed by his people, united by common trauma, to help them survive. This was not the future he envisioned.

When life was relatively peaceful, Gabriel promised himself that he would save some money and complete his university studies. Just before the attacks became severe, he was in his first year while maintaining his farmlands and caring for his family. He really wanted to get a university degree. Then the conflict heightened.

“We were in our villages and all of a sudden, we saw the herders troop in their numbers more than usual. We thought they were just coming to graze their cows but surprisingly, we were seeing them with arms. They moved from farms to the villages. In my own village, people were attacked in the night, around 10 p.m. We started hearing cries from the nearby towns and gunshots. As I speak with you, my village, Achakpa, is a no-go area,” he said.

On the other side of the conflict, as a displaced person, leadership awaited him. While he licks his wounds, he gathers strength to supply the same to the thousands in the camp, trying as much as he can to provide a community alongside other members of the camp management. Sometimes, the life he used to have flashes before his eyes and he is reminded of what “I can never get back. There is no hope of getting it back.

“All my farms – with cassava and yams – everything was destroyed. My house was burnt. Nothing was taken out. I moved here with my wife, my mother, my seven children, and my late elder brother’s children,” Gabriel painfully narrated.

Women bear weights of different kinds

When you spend time in Tse Yandev camp, the women stand-out as they move around fixing, caring, working or just entertaining themselves and the children with folklore. There are three times more women than men in the camp.

As at Oct. 2021, the number of adults over 30 years old in the camp were 6, 110 out of which 5, 125 are women and the remaining 985 are men. Many of the women were widowed by the conflict and suffered varying levels of injuries themselves. Some bear deformities for life but carry on with holding their households together.

Those whose husbands are in the camp, have to support by searching for food in places the men would rather not, like the rice mill where they pick rice chaffs or join their husbands to work on other people’s farms. For the women, the goal is to get their families fed and it is a mission that consumes them because of the prevalent hunger. There is hardly any space to hope for anything else.

“Things hard o. Things hard,” Veronica Namsoor repeated as she shook her head and chuckled lightly. At 25 years old, there was no sign of youth on her face as she sat on a bench that threatened to break her frail bones, and nursed her baby. She pushed her breast into the baby’s mouth, slapping it as if to provoke the milk out then leaving it to fall down her chest while the baby suckled. The child did a lot of the work, labouring for the milk that his mother struggled to provide because she fed him way more than she could afford to feed herself. She, like many mothers in the camp, suffers malnutrition that the children inevitably suffer. But food never was a problem before.

“I was a farmer and a tailor. Now I cannot do that anymore. All our crops were burnt. My husband sometimes joins people to grind things at the engine so we can afford one modu (cup) of corn. Sometimes, I go to the rice mill to blow the chaffs so I can remove the seed and feed my children. Other times, we rely on aid. Sometimes, I farm for other people so I can feed my family,” she said.

Veronica and her husband struggle to feed their four children – nine years old, five years old, three years old and the four-month-old baby whom they are a little glad needs breast milk and is technically one less mouth to feed.

This life, that they now live, is punctuated by recurring diseases, extreme period poverty and a continuous lack that is a far cry from the life they used to have. This is the reality for the thousands of them. As at Oct. 2021, about 1,584 children are between 0-14 years old, 533 are between the ages of 15-19 years old, 550 of the IDPs are between the ages of 20-24 years old and 725 are between the ages of 25-29 years old.

Leaders of tomorrow, how?

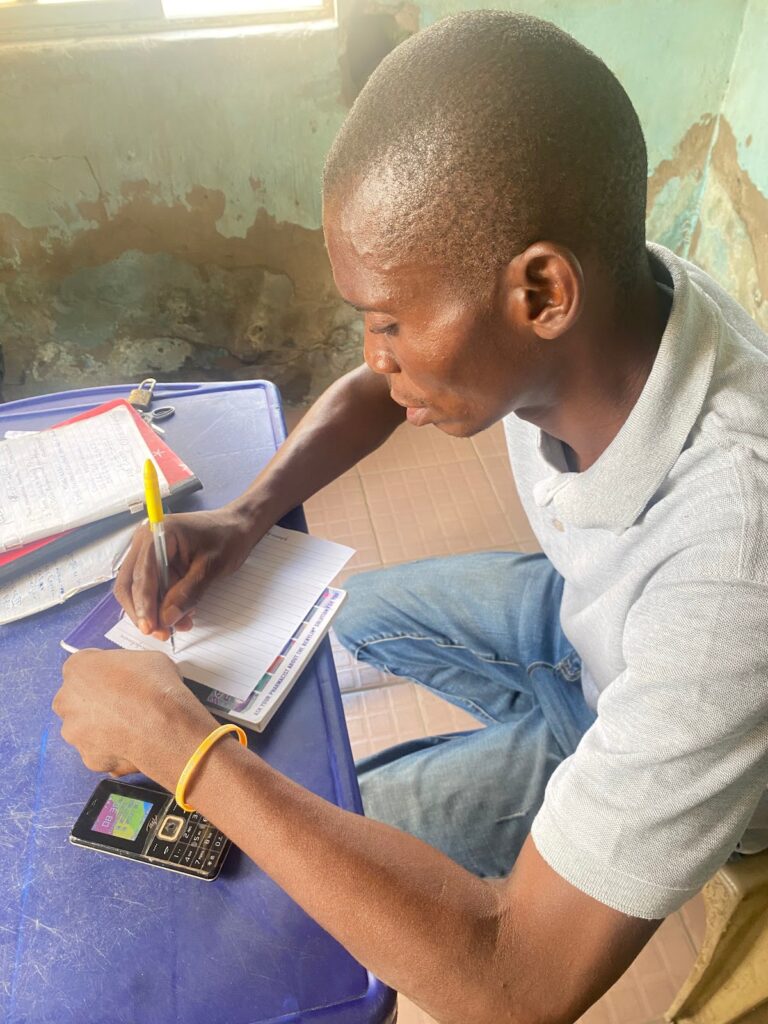

Michael Bature is leading the camp in some capacity as a youth leader. The young man in his mid-20s has a quiet disposition about him and talks in a very measured way. As a child, he had dreams of education but tragedy struck and he is far from achieving those dreams.

“My life is on hold. Our lives are on hold. We had to run away from our villages to save our lives. They were shooting on sight as we were running. We were 11 in my family when we were attacked. One died and the other 10 of us came here. I have six sisters and three brothers. We landed in an IDP camp and now, nothing is moving.”

Michael’s frustrations are echoed by other young people in the camp who feel that their chances of getting an education and having better lives have been cut short; and that the opportunities are no longer available to them.

20-year-old Rebecca Achaku finished her Senior Secondary School Certificate Examinations (SSCE) and landed in a quagmire – no hope of a university education.

“Hunger is our biggest problem here, everyday. But I want to become a lawyer. I really want to. I love the profession but now, there is no hope anymore as my father is dead,” Rebecca lamented.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter