‘Yan Daba: The Local Gangs Terrorising Kano Neighbourhoods

The term ‘yan daba’ took on a new meaning when some youths began associating with them and engaging in antisocial behaviour such as drug abuse, petty robbery, phone snatching, and political thuggery.

A blow to the back, a stab in the face, and then … darkness, a total void with deafening silence.

That was all Mubarak Aliko could recall before finding himself in a hospital bed surrounded by a doctor and family members. He felt his face swollen and moved his hands slowly to touch the fresh stitches that ran from the top of his eyes to the edges of his nose. And then, like a flashlight, he recalled what happened before his ordeal.

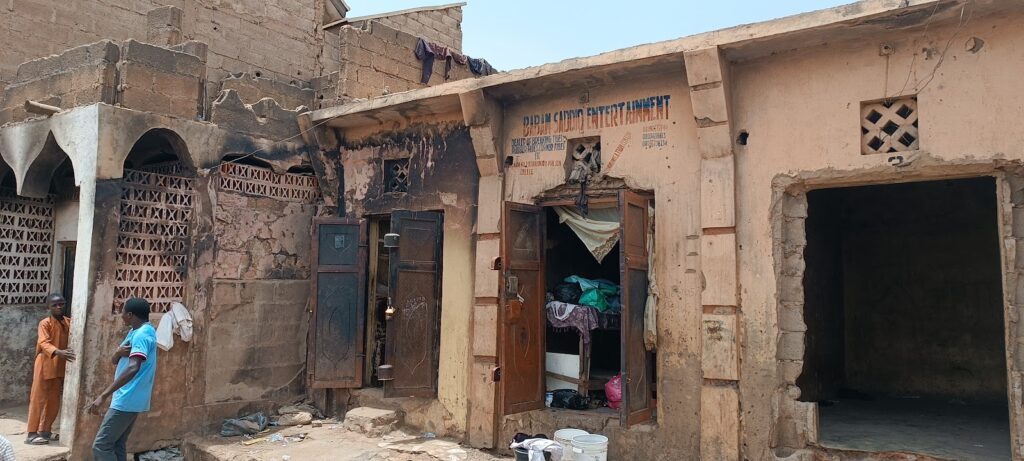

Attacks on passers-by have become frequent in the Madigawa area of Kano, northwestern Nigeria, forcing many residents to lock themselves indoors in the early evening to remain safe. The criminals are known to destroy kiosks and unfinished structures, remove gates and railings, and raze shops.

Two weeks before Aliko’s brutal experience, the criminals, moving in hundreds, had razed all the shops in the area, including the newly constructed kiosk owned by Hassan Iliyasu. “They usually come to rob people of their properties, but that fateful day, they found no one because we closed early, and that was the reason they burnt down shops,” he told HumAngle.

Videos that circulated on social media showed a similar incident in Yalwa, an area not very far from Madigawa. One footage showed about 50 people moving in separate groups, all carrying bright security torches meant to temporarily blind whoever approached them.

That was all known to Aliko. But as a staunch football fan, he planned how he could navigate the situation to watch a sensational match between Real Madrid and Manchester City in a nearby local cinema. He decided to go and planned to return with others after the game.

“I thought it would be more advantageous if I were accompanied by others,” he reflected. According to him, the criminals rarely attack when they see people move in large numbers. They prefer attacking and robbing a few armless people who could easily be overpowered.

The day came, the match ended and Aliko, along with many other people from the cinema, began making their way home at around 9 p.m. At every corner, two or more people would leave and the number kept decreasing. Eventually, he was left in the company of a friend from the same neighbourhood.

They encountered teenagers standing at the crossroads of Dala Cemetery and Kuka-Bulukiyya Primary School. There were only two of them, so he didn’t think much of it because their stature was clearly dwarfed by his. Moreover, he was in the company of another man. “We moved ahead, passing through the dangerous road,” Aliko remembered.

Then, they met another group of four teenagers who suddenly emerged from the darkness. “They were all armed with sticks, cutlasses, and knives,” he recalled. Immediately they saw them, they started running. Aliko ran to the back and his friend to the front. That was when he fell into the trap. The two youths he had left behind emerged from their hiding place and pounced on him as he retreated, preventing him from escaping.

“I thought they would ask for my phone, which I already left at home,” he said. However, they made no such request. Instead, one of them gave him a powerful blow on the neck and then another one stabbed him in the face as he tried to run.

“And that was how I woke up and found myself in a hospital bed.”

Baba Magajiya, Aliko’s sick grandma, saw what had happened to her grandson. But that was not the first close call she had had with the thugs. She had seen them before — inside her home. In the month of Ramadan, corresponding to early April 2024, they had followed a woman who — along with two of her children — sought safety in Magajiya’s bathroom.

“I suspected they were trying to rob her of her phone or other belongings. She resisted and ran for safety,” Magajiya said. The criminals barged into the house and one of them yelled out that he would kill her and her children if she stayed inside. At that moment, the children were crying. One of the boys pounded on the door of Magajiya’s room and found her lying in a sick bed.

“I refused to say anything but I watched them searching from one room to another until they reached our food store,” she said. When they found some valuable items, the criminals changed their minds. Instead of focusing on the woman they followed, they began stealing food and other household goods as soon as they discovered what was in the store.

Aliko and Magajiya’s stories echo throughout the streets of neighbouring Kulkul and as far as Dorayi. The presence of criminals — mostly male teenagers known locally as ‘yan daba — casts a problematic shadow over the daily lives of residents. The criminals operate with brazen impunity, their numbers swelling as they prowl the streets in search of victims.

Hardly anyone is safe from their grasp. They strike without warning, preying on any unfortunate person who dares to venture into the night. Sometimes, they move during the day, but they mostly operate under the cover of darkness, where they lurk and pounce on the unsuspecting.

Hauwa Sani was also a victim in Dorayi. She told HumAngle how she escaped with her life after the criminals chased her, trying to confiscate her phone. “When I saw them near me from behind, I threw away the phone and that distracted their attention,” she said.

In newly built areas like Kuyan Layout in Gwale and Kumbotso Local Government Areas (LGAs), they often stormed people’s houses and robbed them of their properties. “That forced us to form a vigilante group,” said Gajere Maigadi.

From rivalry to robbery

Some decades ago, the thugs referred to as ‘yan daba (literally gangsters) were adventurous hunters. Different clans or gangs would gather while hunting or in a musical ceremony known as “gangi” to laud and demonstrate their strength. ‘Yan daba occasionally fought each other, particularly in hunting rivalries, but they rarely engaged in criminal activity outside their domain.

Later, the term “yan daba” (singular: dan daba) took on a new meaning when some youths began associating with them and engaging in antisocial behaviour such as drug abuse, petty robbery, phone snatching, and political thuggery.

Political activism has historically been the catalyst for transforming local hunters into competing gangsters. Between 1954 and 1966, Kano’s largest opposition party, the Northern Elements Progressive Union (NEPU), was persecuted by the ruling National Party of Nigeria (NPN) and the royal elite. Feeling unsafe by the police, they began using local hunters for self-defence at political gatherings. This caused the opposing party to form its own group, which sparked the fights that went on beyond the First Republic.

However, these political thugs did not become full-fledged gangs until the early 1980s, when they were divided between Easterners (‘Yan Gabas) and Westerners (‘Yan Yamma). Boys and young men aged 10 to 30 began attacking anyone they perceived to be from a specific neighbourhood, even if they were not involved in gang activities. Several persons were killed or injured.

A study done in 2014 linked the behaviour of these criminal groups to poverty, illiteracy, drug abuse, broken homes, and a lack of socioeconomic stability.

Since the restoration of democracy in 1999, the gangsters have been hired for campaigns and political thuggery. Young people are employed to launch attacks on opposition parties during campaigns or disrupt voting procedures.

Currently, it’s the innocent people who are at the receiving end of the gang activities in Kano city. After the election season, these gangs are left without income and resort to illegal activities.

Recently, in April, over a hundred of them were arrested and paraded by the Kano State Police Command after they were accused of waging a broad daylight attack in Dorayi, Gwale LGA. However, the Police Public Relations Officer, Abdullahi Kiyawa, lamented that their efforts are often sabotaged by the parents of such gangsters.

Lawal Hussaini, the member representing Dala in the Kano State House of Assembly, had raised a motion for increasing security in some areas he described as the major hotspots in his constituency where no less than seven people were recently killed due to the activities of the gangs.

Lurking in the den

From the edges of Madigawa to the corners leading to Dala Hill lies a vast, uneven football field where kids run around and play in the afternoon and drug addicts hide to consume all kinds of substances in the evening. The place hosts the gang members as they smoke Indian hemp, inject themselves with substances, and sniff solution gum.

Known as ‘Yan Kadi, it was a lake used by fishermen. But the lake has dried up, transforming into a football field and the meeting point of thugs, who come from Adakawa, Gwammaja, Yalwa, and so on, and gather there to launch assaults on the Dala and Madigawa neighbourhoods.

“This place is our biggest problem,” said Usman Sidi Musa, a local vigilante. He claims that drug users could be more easily scattered or arrested when water was readily available in the lake. However, whenever police or local vigilantes attempt to launch their operations, they can now escape via various routes that formerly were full of water.

In April 2024, after returning to exact revenge for the death of one of their own, the gangs surrounded and clashed with vigilantes in Madigawa through ‘Yan Kadi. “They hide behind garbage and a few holes here, so nobody saw them before they pounced,” said Haruna Musa. “We could have overpowered them, but they divided our attention. If you finish with some, others come out of nowhere,” he explained.

Musa was recovering from an injury he sustained in his left arm after he was beaten with a stick by the mobs.

Everyone in the Madigawa communities interviewed by HumAngle agreed that the ‘Yan Kadi is the biggest problem in finding a lasting solution to the insecurity in the area. They also said they would never be able to relax their tensions until something is done about it.

“There are many uncompleted buildings around it and we appealed to the owners to finish their building or sell it to a capable person for our safety,” Magajiya said.

Prior to the 2023 general elections, politicians from various parties promised to construct a school, hospital, and security outpost there. “But it’s almost a year since they assumed office, but not a single building block has been brought here,” said a disappointed Musa.

He added that the major work to bring a lasting solution to the problem lies in the hands of parents. “Charity begins at home. Some parents protect their children who have joined criminal gangs whenever they are to be arrested,” he claimed, adding that this only emboldens their criminal activities.

Umar Abba, the Mai Unguwa (Ward Head) of Tudun Makera, confirmed this when he told HumAngle how he faced resistance from some parents after their children’s arrest. “Some of them take us as their enemies even when we are trying to protect others from their children,” he said.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter