What Is The Real Cause Of Attacks In Nigeria’s Middle Belt?

As insurgents from the North East and terrorists from the North West spread across the northern region, there are speculations as to the real reasons for the persistent Middle Belt conflict. Is it a result of the spread of these armed groups, or is there a much deeper history?

There are different perspectives on the cause of the lingering conflict within Nigeria’s Middle Belt states. Some reports have ascribed the bloodletting in the last couple of years to the influx of Boko Haram terrorists. Others point to the history of conflict between farmers and herders that has seen some of the states host the largest number of internally displaced people (IDPs) outside the North East as of 2020.

The struggle for ethnic and religious dominance is also another factor that has been identified as the trigger for violence. Then also, the activities of terrorists, commonly referred to as bandits in the northwestern and north-central regions.

A local like Yunus Anas, who witnessed the 2001 Jos crisis that claimed thousands of lives, views the recurring attacks as a complete departure from the ethnoreligious clashes of years past. “What is obtained now is a pure act of criminality without any ethnic or religious colouration,” he told HumAngle.

But Kate Garba, who resides in the Mangu area, one of the current hotspots, describes the tragedy as a clear act of terror. “They are well-organised,” she said.

However, experts who spoke to HumAngle said that the indigene/settler dichotomy is arguably the strongest reason for the spate of attacks in the area.

Circle of violence

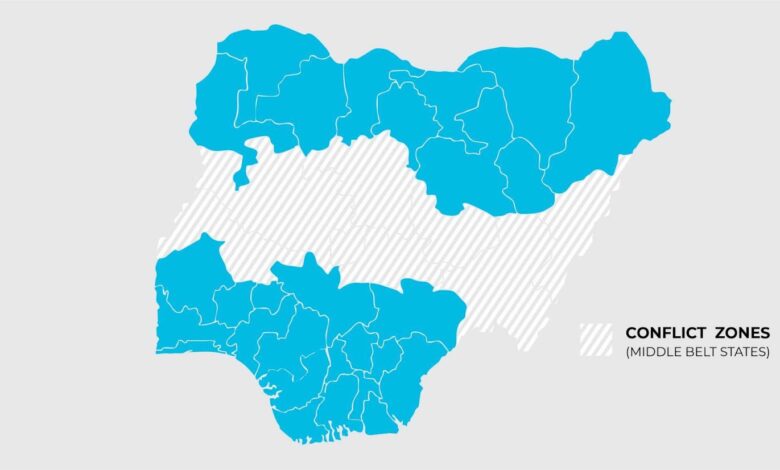

Nigeria’s Middle Belt states include Adamawa, Kaduna, Kogi, Kwara, Nasarawa, Niger, Plateau, Taraba, and the Federal Capital Territory. Some of these states are not new to ethno-religious or farmer-herder conflicts, particularly Plateau and Benue in the North-central and Kaduna in the North West.

On Christmas Eve of 2023, something devastating happened in Plateau State – gunmen on motorcycles and on foot invaded more than 20 communities in separate but coordinated attacks. The targets were the Bokkos and Barkin Ladi local government areas (LGAs).

Witnesses said in a documentary by Channels TV that the assailants went from house to house bearing guns and machetes. They killed over 150 people and set dozens of houses ablaze. In Barkin Ladi, David Nanbet said, they operated for about seven hours.

These attacks later spread to Mangu LGA, an area that experienced wanton killings in 2023. These happened despite the security manpower and equipment deployed to checkmate the recurring terror in the region.

This year, notably from Jan. 23, clashes with an ethno-religious undertone erupted as distrust intensified in Plateau, leading to a curfew pronouncement by the state government.

On Dec. 18, barely a week to Christmas in 2022, a similar scenario played out in Southern Kaduna, which, like Plateau, is predominantly Christian. Two communities in Kaura LGA, Malagum 1 and Sokwong, under the Gworog (Kagoro) chiefdom, were attacked. Not less than two dozen people were killed, and many houses burned down. An eyewitness, Baba Yayok, said he heard the perpetrators chanting “Allahu Akbar”, meaning God is the greatest, used by Muslims in prayer or as a declaration of faith.

There were several other incidents in Southern Kaduna that were a replication of this type of terror. The state government described one in Zangon Kataf in 2021 as a “reprisal to earlier attacks”.

In the past few weeks, up to 38 persons were killed in several Benue communities. According to Premium Times, gunmen attacked Ogwumogbo, Ikpele, and Ejima villages of Agatu LGA on Jan. 27 and started shooting sporadically.

What is responsible?

To understand this tragedy, HumAngle spoke to Dr Murtala Ahmad Rufa’i, who lectures at Usman Danfodiyo University’s Department of History and International Studies in Sokoto. He has done extensive research on conflict, particularly in the North West and in the Middle Belt.

“The issue you see in the Middle Belt revolves around the highest forms of injustice, corruption, ethnic profiling, marginalisation and then other livelihood issues that keep on occurring here and there,” Rufa’i said.

He explained that the conflict has less to do with the wider notion of terrorism and violent extremism, rather, it still revolves around the indigene/settler question, which has remained unresolved.

“It has its own layers and faces, and at times, it takes a herder-farmer dimension,” he said. But, sometimes, it has a religious connotation.

“Because in these areas we are talking about, we can never dispute the fact that there are non-indigenes and also indigenes who are there by birth. And they are not considered by the indigenous people as indigenes. Even though they have a second home which is outside the region and outside the zone, their first home is where they reside.”

Rufai pointed out that there are indigenous Hausa and Fulani in Jos, Benue, and Southern Kaduna. Although they have their lineage from the far north, comprising states like Jigawa, Kano, Katsina, Kebbi, Sokoto, Zamfara, and the rest, they consider the Middle Belt their first home because they reside there.

“They feel they are indigenes like any other indigene and are entitled to whatever resources one could see in the Middle Belt. They feel they are Muslims. Their religion, ideology, and teachings need not only to be protected but promoted. And they could go any length to protect their religious integrity and identity,” Rufai said.

Sometimes, when there is conflict, the Hausa and Fulani in the Middle Belt are able to get sympathy from the far north because they relate with their own people there.

Dogo Gonet, a historian based in Plateau, agrees that the conflict is tied to the indigene/settler question. As far as he is concerned, it is that contestation that drives the struggle for political power.

“There is what we call political economy. You don’t just own land. You need political power in order to own that land. So, contestation could be over land because the land has a political and economic system. If you occupy a space and then elections come and the population is beginning to compete on a tight basis, automatically you would see that people begin to interpret them in different ways,” he told HumAngle.

Gonet says there is the fear that one group can have a greater population and take over political power. A 2011 report by the Geneva Declaration on Armed Violence and Development shows just how much of a disaster this can generate.

The report blamed various factors for the crisis in Plateau, including “tensions between ethnic groups rooted in the allocation of resources, electoral competition, fears of religious domination, and contested land rights”. The circulation of guns and the presence of organised armed groups in rural communities have also rendered the region more unstable.

“Today, the ownership of Jos and claims to ‘indigene’ status are fiercely contested between the native tribes and the Hausa,” the report further stated.

“Indigene certificates ensure access to political representation and positions within the civil service. Only local governments issue these certificates and, therefore, decide on indigene status. This arrangement opened the floodgates for the politics of labelling and the selective reciting of historical accounts that foster group boundaries to secure political control over local government areas.”

Bigger than it seems

Apart from the far northern states, the Fulani have relatives and friends in countries such as Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, Mali, Senegal, Togo and so on, Rufa’i explained.

“When you kill a Fulani man or attack cattle in Benue, don’t just feel that you are attacking the cattle of that person who owns it. The tradition is such that, even if I am rich as a Fulani man with 10,000 heads of cattle, it is wrong of me as a person to put that cattle together and continue herding or taking care of them. Rather, I distribute. Ten in Sokoto, 10 in Kaduna, 10 in Katsina, 20 in Niger, 10 in Mali. That explains the relationship.

“So, if you touch a herd of cattle here in Benue or Jos, Plateau, that particular person who looks after the cattle would extend his grievances, his fear, his challenges, his problems, to his brother in Mali. And he invites him to any action or inaction. In such a situation, it is compulsory for his brother abroad to honour that invitation.”

That is what brought about the kola nut culture among the Fulani people, he added. Whenever there is a crisis, the Fulani distribute the kola nut as a form of invitation. The porousness of the country’s borders has made it easy for such movements to take place without checks.

Flaws in conflict resolution

Rufa’i mentioned that there are killings of those termed as non-indigenes in the Middle Belt that are not reported by the media. “We have seen a lot of reports in the field – killings of Hausa, killings of Fulani people, mass killing of cattle, and gross injustice against these communities.”

There are also cases in the far north of farm destruction, of animals going into farms, leading to conflict and violence. But this is still different from what is seen in the Middle Belt, Rufa’i insisted.

And there is a clear reason for this.

He explained that traditional authorities in the far north consider the Hausa and Fulani, the farmer and the herder as part of them. So, “when it comes to issues of arbitration, they try as much as possible to be fair. In cases like this, you see them even punishing the farmers where they go wrong.”

Another important issue, Rufa’i pointed out, is that the Fulani people in the far north, irrespective of what is happening in the North West today, still have a certain level of respect for traditional institutions.

“They are part and parcel of the traditional conflict resolution mechanism,” he said. “And you see that they have a representative in the palace or the house of the district head, who is part of them and whom they report to these issues of injustice. You see them being addressed. At the end of the entire exercise, both parties would feel comfortable and satisfied.”

But in the case of the Middle Belt, Rufa’i said, the traditional authorities are one-sided and consider only those they call the indigenes as their own.

“That is a very big problem and it is why this conflict has lingered so long. Until these traditional authorities feel they are there for all, they are there to protect the interests of all, that is when we are going to have peace.”

He added that the representation of the Hausa and Fulani in the Middle Belt’s traditional institutional framework is not effective because those appointed are either not Fulani or do not understand the dynamics of the people. For example, they may not know the difference between the local and rural Fulani.

“Because even within the Fulani, we see a lot of differences and dichotomy and a lot of internal conflict. It is only those who are in the far north that understand this. If you mention the Fulani, there are about 15 to 20 clans. And you find out that they are not in agreement with each other. But what we see in the Middle Belt is that, since they find themselves in the land which is said not to be theirs, they mostly decide to unite, but their differences are still inbuilt.”

Unity among the various Fulani clans becomes evident when they face a common enemy, Rufa’i said. This is why the issue of reprisal attacks will remain as long as justice is not provided and ethnic profiling is not addressed. “As long as someone is considered an indigene and the other is considered as non-indigene. Because you can’t imagine someone who has been in Benue for 60 to 70 years, 80 to 100 years and overnight is considered as a non-indigene.”

Are the attackers militias?

There have been speculations that militias are invited or hired from outside the country to launch attacks in the Middle Belt. Rufai believes the attackers are not militias but rather stakeholders in the conflict who are trying to protect their economic interests through violence.

Meanwhile, Gonet pointed out that there is a deeper history to the conflict. He sees it as a repeat of the Usman Danfodiyo Jihad of 1804. During that period, the Plateau and adjoining lowlands in the middle belt were enveloped.

“Many militants had to leave the northern area into this area,” he said.

Many people became flag bearers in places like Zaria and Bauchi, agreeing to expand the war. “The moment you collect the flag from the source, your area becomes a vassal area so that you can now extend it as a forward operating base,” he explained. “Many people after the war collected the flags and became commanders of the jihad. So even when the war had stopped in the north, it was still raging in these areas. They were expanding the sphere of influence of the war. That is the first factor.”

Many combatants settled in the middle belt for this reason.

Another factor is the richness of the land in these areas for grazing.

The third factor, Gonet argued, is ideology in terms of ethnic superiority. “The aggressors at the moment, in terms of whether they are bandits, herders, terrorists or whatsoever, I feel that they have a particular ideology in them, whether it is in terms of religion or normal belief system. Whatever it is, they believe that the whole of this area [Middle Belt] belongs to them.”

He added that colonialism aided the expansion of this belief system because it helped to widen the sphere of influence to even areas that resisted during the 19th-century jihad.

Some have proposed restructuring as a solution to the conflict, but there is no agreement on exactly what this entails.

“To the Middle Belt, it is when you carve out all the Christian areas. But it is mixed, so if you carve it out, somebody in Nasarawa would say he is not part of the Middle Belt because he is not a Christian. There are people who, if you ask them to talk about the Middle Belt, they won’t talk about it geographically. They would start talking about Christian-dominated areas such as Southern Borno and Southern Kebbi where there are Zurus.”

For Gonet, the true solution is to ensure there is justice, which could lead to fewer grievances and fewer calls for self-determination or agitation.

“I believe, in a plural society such as ours, when there is social justice people feel a sense of belonging. But the moment we begin to use the currency of religion, it will be countered.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter