The Fight Against Boko Haram Leaves A Trail Of Ruin And Ashes

The terrorists took extreme measures to keep them in their ancestral communities; the soldiers took extreme — even unlawful — measures to push them out.

Zara Goni remembers.

It was a Wednesday in June 2014, around 8 a.m. Her people had scuttled indoors when they heard trucks pulling closer as the soldiers inside them launched bullets in different directions. The gunshots continued for a long time. The villagers heard something else, too: the cracking sound of things burning. Outside, the house’s shade, made of sticks and grass, was darkening, shrinking, and falling apart. Fortunately, the fire did not creep into the mud room where Zara hid with the rest of her family. But her husband, Abatcha Goni, was not with them. He had stepped out earlier to attend a relative’s burial ceremony. When the soldiers climbed back into their trucks and zoomed off later that afternoon, Zara came out of hiding to find that a large chunk of her community had been burnt to the ground. Worse, Abatcha had sat under a tree with three other people at the function. They were all shot dead.

There was another burial ceremony that evening.

This tragedy stamped its feet in Awada, a community in the Mafa area of Borno, northeastern Nigeria, with over a thousand households. That day, the spring green from tamarind trees spread over its landscape became blemished with depressing shades of brown and grey and black that whisper defeat after a battle with fire.

For a decade and a half now, Nigeria has been at war with violent extremists, a war that has directly and indirectly cost the lives of nearly 350,000 people. It started when a group that came to be known as Boko Haram started radicalising people in the early 2000s and later decided to forcefully carve out parts of the country to establish a caliphate. Boko Haram has since splintered, leading to the establishment of two other terror groups, the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) and Ansaru, both having strong links with international jihadist networks. Many years into the insurgency, the authorities still struggle to restore peace to the region.

Much has been said about the damage caused by weapons in this war, of the heads lost to machetes, of the limbs lost to bombs, and of the lives lost to bullets. But a trip across the conflict-ravaged communities of Borno would reveal another destructive force — fire, including the ones ignited by government forces.

Last December, HumAngle spoke to a dozen people who lived in areas that are dangerously close to the strongholds of jihadist groups and whose communities were destroyed by state forces — just like Awada. Many of the displaced townspeople told stories of loss — of loved ones and valuables — following military invasions.

Such disproportional military tactics are not new. Chidi Nwaonu, a security analyst, says the use of collective punishment is a hangover from the colonial period that is “unfortunately baked into the psyche of the security forces, political class and even population as an appropriate response” in certain instances.

Nigerian Army spokespersons who commented on our findings described the allegations as false and flimsy, suggesting that the attacks may have been conducted by terrorists dressed as soldiers and that some of the incidents may have been cases of collateral damage. They also stressed that the Army does not condone such actions.

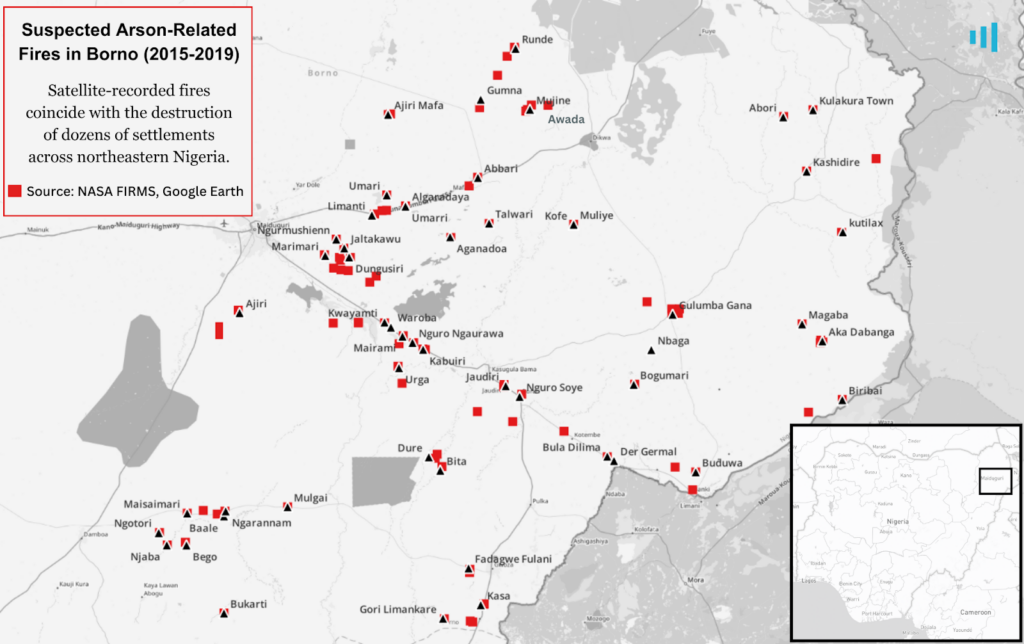

However, the military’s claims are contradicted by our investigation. In addition to interviews with victims, we used satellite data from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and Google Earth to establish a pattern of fire outbreaks consuming dozens of settlements and towns across Borno. Nigerian Army officers, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, also confirmed that the military had carried out such actions as a form of reprisal when communities came under suspicion of aiding militants.

Such arson attacks affecting civilian communities have gone on for many years despite several domestic and international laws prohibiting the destruction of dwelling houses as well as forced displacement during conflicts.

Meanwhile, the interviews we conducted indicate that once they start, the attacks and arsons usually happen repeatedly. Four months after the Wednesday attack in Awada, the soldiers came again. This time around, Zara said, they killed 12 men and again set fire to houses. There was a third visit in the same period when the soldiers relocated the townspeople to Dikwa and Maiduguri, the state capital.

“They brought many cars to pick us up,” recounted the mother of five. “They said, ‘We are taking you to where there is order.’ Some of us were taken to the Muna displacement camp and others to Custom House.”

Two years later, in 2016, Bogomari, a faraway village in the Bama area, was burned down. There were four more incidents between then and when 30-year-old IDP Zainab Modu finally left in September 2023. Abba Konto, who operated the community’s borehole before Boko Haram destroyed it, left around the same time. He said nothing is even left that could be burned anymore. “Now the people stay in leather tents like nomads. They would run if they heard the sounds of cars approaching.”

In some of the communities, houses were destroyed so often that people resorted to makeshift shelters instead of taking time to build mud structures. They also devised new means of storing their food supplies to protect them from such attacks.

The embers are still hot

When it happened in Dauleri two years ago, the terrorists had struck first. They attacked a military post at a central junction not too far from the community. The soldiers zoomed past the village as they chased after them. It was a regular day in these parts. The people who had lived here all their lives had gotten used to gunfire. But they were not expecting what happened after the hot pursuit.

“They did not spare any house,” recalled 25-year-old Ali Modu. He wore a sad expression as he spoke and rested his face on his right palm afterwards. “Nothing was spared. When we came out of hiding, only our grain barns were still smoking, but they had also been destroyed. Everywhere else was in ashes. Everyone was heartbroken.”

It was just after the rainy season. It was supposed to be a time for harvests.

The people of Dauleri, as did many others, faced onslaughts from all sides of the war. “Boko Haram killed us because we were different from them,” Ali mulled. They weren’t safe from soldiers either, who burnt their houses and foodstuff and also killed their loved ones.

After the first incident, most of the villagers immediately left for a displacement camp in the garrison town of Bama. Others returned to Dauleri — first settling in a neighbouring village, hoping to rebuild their lives, hoping the mass destruction was a twist of fate unlikely to repeat itself.

About a year later, during another harvest season, it happened again.

They burned the whole village,” Ali said. Between those two incidents, there were a few other times fire was set to several houses in the community. Eventually, his family and others decided to leave when they no longer had food and shelter.

Dauleri is deserted now.

We established this pattern in various communities across the local government areas of Bama, Dikwa, Mafa, and Marte. In some cases, locals told us of villages surrounding their own that were also affected.

For example, according to Rumaida Abubakar, 75, who is from Zawara in Marte, besides his village, the whole ward of Gumna is currently abandoned. He claimed that Gumna town, the ward headquarters, was destroyed, as well as surrounding villages such as Bucha, Fala Fala, Gumna Bula Abubakar, Gumna Kayeya, Ilewaya, Keza, Mulfe Balalam, and Mulfe Durma.

Amnesty International has confirmed some of these operations in a 2020 report through interviews with affected people from three Borno communities, and satellite image analysis.

The advocacy group’s former country director, Osai Ojigho, observed at the time that “these brazen acts of razing entire villages, deliberately destroying civilian homes and forcibly displacing their inhabitants with no imperative military grounds, should be investigated as possible war crimes.”

Meanwhile, such incidents are not limited to counterinsurgency operations in the Lake Chad region. We have seen Nigeria’s armed forces adopt similar methods in other parts of Nigeria. For example, in 2018, a group of soldiers burnt many houses in the Gwer area of the North-central region, reacting to the killing of their colleague by hoodlums. In 2023, similar circumstances led to the burning of shops, hotels, and markets in the southeastern state of Imo.

Cause of death: (gun)fire

When the soldiers ride in on a storm of bullets, multiple accounts suggest that the villagers immediately leave what they are doing and run towards the bush, where they hide for anything between some hours to several days, depending on how long the soldiers hang around. Sometimes, women gather together and are left unhurt.

Sometimes, those who are not able to flee fast enough are gunned down.

“If it is an old person, they would take them, and if it is a young person, they would kill them,” alleged Musa. In some other communities, old people were not so lucky.

Ali’s grandparent, 60-year-old Kaka Modu, was one of the six to seven people killed in Dauleri. Some of the others, he said, were Babor, who was about 40 years old; Ba Usman, also about 40 years old; Ba Ali, who was between ages 30 and 35; and Ya Bintu, an elderly woman. They also lost about ten children to disease and starvation, having had their food supplies consumed by fire.

“They killed three people,” recalled Ruko Abatacha of Mujigne.

“They came around 10 a.m. and started chasing us away. We were hiding in the room. They flogged us and sent us out of the room. They hit me with a stick on my hand and injured me. They set fire to my house and two of my neighbours’ houses before we left for Dandal.”

There had been no prior warning, he added.

Zaram spoke of how in Gudusuri, the soldiers killed five people who made to run the second time they came, then they killed another ten people, and then another seven.

“Sometimes, they burned rooms with small children in them and sometimes even grown-ups,” she continued. “The first time, they burned a room with five people — two children and three adults — and the second time with nine children.”

Four-year-old Ibrahim and three-year-old Adam were some of those children, she said.

These incidents of houses getting burned with people inside them may not have been deliberate. HumAngle received another report of an old woman in Zai, a community in Dikwa, who hid in a maize thatch, which soldiers unknowingly set fire to sometime in 2019.

An Amnesty International report, which focused on older conflict victims in the region and was released in 2020, contained several similar accounts: of soldiers shooting at people in their homes or trying to flee and setting houses on fire — sometimes with the bodies of people they had just shot inside or with the inhabitants still alive. One farmer from a village in Bama claimed that they burned a house that had an old woman and her six-month-old grandchild.

“They went looking for Boko Haram to fix the problem. If they can’t find Boko Haram, they will then wreak havoc on the common person.”

— Zainab Modu

Losses too great to count

Before the Boko Haram insurgency, most rural people lived a modest life. They had enough to feed themselves and take care of other needs from their farm produce and livestock. And then the wildfire of war flooded their homes. The terrorists restricted their freedoms, declaring that they were now part of their daulat (occupied territory). They corrected how they prayed. They burnt their schools because God forbid they get educated according to Western standards. They abducted residents. They conscripted their young men and forcefully married off their girls. They slaughtered parents who objected. They acted like they were entitled to their properties and means of sustenance. They took their harvests and often left with their livestock until there was nothing left. They looted their cars, motorcycles, bicycles, and money. In some cases, they killed the villagers as they stole from them. They returned at night to steal some more. Sometimes, they bought food and other commodities from their markets. Then the military came and painted everyone with broad strokes of suspicion, accusing the locals of being Boko Haram members and often killing in the process.

Rumaida confirmed that the civilians were not armed. “This is why we were confused,” he said. “You are just a poor man sitting. When the military came to search for terrorists, they killed civilians in the name of Boko Haram. That time, we had three options if we wanted to remain alive: to go to Monguno, Dikwa, or Maiduguri.”

He chose to go to Dikwa.

“We left all our belongings there; even buckets, some plastic, mattresses, everything, we left them. We came with only our clothes,” he said.

Asked if he still had any livestock with him, he laughed and said: “I have become poor. I have become elderly, and there are no animals.”

Ali and his family in Dauleri lost many things to the fire, too, all running into millions of naira. Some of the items that stand out for him include motorcycles belonging to his father, grandfather, and uncles, a new set of furniture belonging to his newlywed sister, and grains.

Life has been tough for him since his displacement. He had not been able to register himself and his family – wife and six children – at the camp ten months since he arrived. He was repeatedly told it was not yet his turn. He had to pay to set up his shelter. He currently labours on an onion farm to fend for his family. “We are just struggling to survive, and I have not gotten even an ounce of grain since I came,” he said.

Zainab from Bogomari shared a similar experience. Houses and grains were burnt. Animals went missing — and so did foodstuff, “even the ones that were buried”.

Another account from a different village was that the soldiers didn’t leave with anything. Instead, they burnt everything, including cows.

When a community loses its food stock to a military raid, its people cope by buying at higher prices from neighbouring villages that weren’t attacked. And then some would choose to work in exchange for food.

“I don’t even know what to do because of sadness. Because they killed our people and made us lose a lot of things. There is no family that was not at a loss.”

— Zaram Mai Bulama

‘Flimsy charges’ — Army

We asked spokespersons of the Nigerian Army about the allegations of arson and extrajudicial killings. They described them as false, flimsy, and illogical.

Director of Army Public Relations Brig. Gen. Onyema Nwachukwu replied that counterterrorism operations have improved over the years because of the experiences gathered and that such allegations were more common during the early days of the crisis.

“We liberated those communities you talked about and we are the ones that took them back to their ancestral communities and back to their ancestral occupation, empowering them. So the same troops cannot go back and begin to set ablaze, like you alleged, communities that were liberated by them. I don’t think that is actually possible. We have gone past all that,” he said over a phone interview.

He explained that sometimes troops apprehend people providing tacit support to insurgents and destroy the items they use to provide such support, such as bicycles and motorbikes. Asked if houses may be affected in such situations, he replied that he “cannot completely rule out what we refer to as collateral damage”.

The spokesperson pointed out that terrorists also impersonate soldiers by wearing military fatigues and commit atrocities, especially by attacking vulnerable civilian targets.

“And the civilians, unfortunately, cannot decipher between our troops and those terrorists when they come for such atrocious attacks,” he added. “So, I believe that most of those arsons you are talking about are actually committed by the terrorists themselves. Why would troops go back and burn a community they liberated? These are just flimsy charges that people are trumping up.”

Brig. Gen. Nwachukwu said the objective of military personnel is to protect people and not destroy communities, but “there is a possibility of collateral damage” during combat engagements.

He also said the Army does not take such conduct lightly and would discipline any officer genuinely found to have destroyed civilian houses and food supplies. “We won’t tolerate such things. That person will be terribly dealt with. There are rules of engagement that are laid down.”

Lt. Col. A.Y. Jingina, spokesperson of the Nigeria Army 7 Division, which was established in 2013 to improve security in the North East, was more emphatic in denying the allegations.

“We have not done anything of such. They are just fabricating lies,” he stated. He further asked anyone with complaints to direct them to the Army’s human rights desk, assuring that they would be ‘looked at’.

Proof from above

We were able to confirm fire incidents in many of the communities by matching victim accounts with Google satellite imagery and data from the Fire Information for Resource Management System (FIRMS), which detects and publishes information about active fires and unusual thermal events.

For example, FIRMS spotted a small-scale fire in Darajamal on Oct. 19, 2016, and then about six larger-scale fire hotspots around the area on Dec. 3 in the same year. Google satellite images showed the community to be intact two years prior to the fire. By Dec. 6, 2016, there was community-wide destruction as the buildings had become scorched.

On Nov. 11, 2018, the fire sensors recorded another incident in Darajamal, followed by three more fires within the vicinity. Again, this is corroborated by satellite images captured days later on Nov. 18 that showed large-scale destruction.

Google imagery showed a few burnt buildings at the northeastern edge of Awada in 2014. But the community remained largely intact for a few years. Then, there were two major fire incidents on Dec. 3, 2016, and Jan. 14, 2017. The next available satellite image of Awada captured in March 2018 showed that it had been completely destroyed by fire.

The same pattern can be seen in Bogomari, which was set ablaze on Jan. 9 and Oct. 10, 2017. No satellite images of the town are available from that period but the data recorded shows that the community had been completely destroyed as of February 2019.

Mujine, a community in Mafa, seemed fine in December 2016. But it was completely razed by March 2018 following a fire incident from January of the same year. The fire sensors recorded four hotspots in Ajiri on April 4, 2016. The destruction that followed remained visible from satellite images captured in November 2017. Over a year later, in July 2019, there was nothing but a huge char spread across the town where buildings used to stand. Then, if we move to the Gumna ward in Marte, we again see evidence of fire in the northwest cluster of settlements in October 2017 and 2018. Satellite imagery from March 2018 showed the community to have been destroyed. The main town of Gumna had also been completely ruined by December 2018.

We interviewed locals from all these communities who confirmed that their residences were destroyed by military personnel.

Further analysis of fire data from FIRMS revealed that more than 50 places across ten local government areas in Borno were unusually burnt down over the last decade, some suffering multiple fire incidents [data available here]. The most affected LGAs were Mafa, Bama, Konduga, and Gwoza.

Without additional information, however, it is impossible to say who was responsible for the fire. Insurgent groups have also often set fire to civilian communities, churches, and schools. One of the more recent attacks happened in February 2020 when Boko Haram terrorists set many houses on fire in Korongilum, a village in the Chibok area of the state. Between 2009, when the war broke out, and 2015, attacks by Boko Haram are noted to have destroyed over 910 schools, many of which were burnt.

Heart of the storm

Many of the communities affected are situated close to insurgent strongholds. Interviews with locals suggest that the soldiers either considered them to be Boko Haram members or allies — or they saw the villages as a source of nourishment for the insurgency, helping the terrorists to stock up on food and other essential supplies.

Ali Modu says Boko Haram fighters did not live with them, but they passed by their community as they headed towards the Sambisa forest area. They also stopped by sometimes to get water and buy food.

For people in Gudusuri, a village in Marte of about 200 households, Boko Haram considered the place as part of its territory and prevented them from leaving. “When they saw us in the bush, they would kill us, saying we were going to the land of disbelievers,” said Zaram Mai Bulama, 22. The insurgents came from the south and would sometimes gather the locals for sermons. The Boko Haram members often did their shopping in the neighbouring village of Meleri, which was so close to Gudusuri that they shared the same borehole. There are only a few trees between the two communities. As far as the soldiers were concerned, they were the same community, observed Zaram.

“The first time the soldiers came, the bulama [village head] was around,” she recalled. They asked who among them was a Boko Haram member. The locals replied no one. The soldiers then chatted with the bulama in Hausa, a language most of the people did not speak. The village head later informed them the soldiers had said they heard the village was full of Boko Haram fighters and trade was ongoing, but they had met a different reality.

When they returned several times afterwards, their visits were not as peaceful. The second time, the people had heard of what happened to surrounding villages and became terrified. When the soldiers approached, the bulama ran with the rest of the people to the bush. The soldiers then set fire to the houses.

“No house was spared except those on the outskirts of the village,” Zaram recalled.

The village was burnt at least twice afterwards, forcing the townspeople to leave for Marte in 2014. Some said they would leave the following morning after the second incident, but Zaram and her family could not wait any longer. That night, after burying the dead, 15 of them packed whatever they could salvage and set out on the journey.

It is important to note that locals may not always be forthright when asked whether their community sheltered terrorists — especially before their displacement.

A vigilante who has worked with the military in Borno on counterinsurgency missions for many years disclosed that in some communities, many of the young men are truly members of Boko Haram. He explained that the villagers would usually feign ignorance, believing that the truth could come back to hurt them.

“They knew their children were members of the terror group. But at the time they burnt and demolished their houses, the terrorists were not staying in the villages; only old men, women, and ordinary civilians were there,” the security agent added, referring specifically now to military raids that affected two communities in the Bama and Konduga areas sometime in 2016.

James Barnett, a specialist in Nigerian politics and security at the Hudson Institute, describes the position of civilians in the region as an impossible one considering how they often face distrust from both insurgents and the military.

“The Army began using scorched earth tactics in the northeast early in the war when its troops were frequently outgunned and overstretched and both the military and local communities had limited knowledge of the insurgents—suspicion therefore abounded,” he said.

“These tactics were never particularly productive, but they were initially a product in part of genuine challenges and constraints on the military’s part, if also reflective of a culture of heavy-handedness and impunity demonstrated over the years in places like Odi, Zaki Biam, Zaria, and elsewhere. The North East is vast and difficult to fully cover militarily, so soldiers may calculate it’s easiest to punish possible collaborators and deny the enemy potential shelter.”

Accounts from displaced people suggest that how state forces determine who is an insurgent and who is not can be quite arbitrary. Running whenever they approached, even if clearly unarmed, was apparently seen as suspicious.

“When they come, they will ask us to raise our hands. If you don’t, they will say you are Boko Haram and shoot you,” said Zaram.

When people in Bula Masu, a community in Darajamal, Bama, had their first encounters with Boko Haram terrorists, they would panic and run towards the bush, where they would meet even more terrorists.

“They told us to stop running and that they would kill anyone who ran away. Then we stopped,” recalled Musa Modu, 30. Later, when the soldiers came around, they scampered towards the surrounding bushes again.

Bula Masu was so close to the stronghold of the terrorists that they asked the townspeople to change the community’s name to Wulte because “Bula Masu is a bad name”. They renamed the weekly market Wulte as well and started patronising it. They could not go to markets in other places because of the presence of soldiers, Musa explained. When he talked about Boko Haram, he crumpled his face and narrowed his eyes as though sipping a sour orange. It was as if he was back in Bula Masu, and the terrorists were before him.

“When they come to the market, they would seize phones from the villagers, do their shopping in a hurry and leave. They collected the phones because they didn’t want us to call Bama,” he said.

He added that people stopped trading at the market after soldiers discovered and burned it, afraid that they would be killed if they continued.

Zainab from Bogomari said that even though there are no terrorists in her village, the neighbouring communities of Kote and Mina were known to harbour Boko Haram members.

It is, however, not clear how effective the forced displacement of communities is in tackling insurgent threats. One former Boko Haram combatant, who spent many years in the bush, narrated how they were unaffected when he was deployed to Sadu. “We had soldiers packing people, but nothing happened to us,” he said. “Even when they were taking people with them and burning houses at Sadu.”

He added that he had witnessed scores of people relocating to the forest areas to join Boko Haram after such destructions.

“They will be asked where they are coming from and why they came. They will say we accepted the preaching and we would not investigate further. From there, some would be taken to the madrasa (school) and other posts.”

Security analysts agree that the tactic can be counterproductive, especially because it undermines civilian confidence in the military and complicates efforts to gather intelligence.

“To the extent that scorched earth tactics contribute to further displacement, it risks creating more IDPs that the insurgents can prey on,” James said.

Chidi Nwaonu believes insurgent groups can also use such measures as a recruitment and radicalisation tool. “Even in the event that the population is hostile, they are not likely to become compliant by attacking them, and if they are neutral or compliant, they become hostile,” he argued.

He added that examples from other parts of the world further show the ineffectiveness of collective punishment tactics, from what the Soviets did in Afghanistan to Russian military operations in Chechnya, Syria, and Ukraine, the Vietnam War, and the current Israeli occupation of Palestine.

“Each of these examples demonstrates the futility of this approach: the Soviets were defeated in Afghanistan, the Russians were successful in Chechnya by coopting the locals after the first and second wars, in Ukraine it has only increased resistance, the US was defeated in Vietnam, and even the IDF’s actions in southern Lebanon did not deter Hamas or Hezbollah.”

No easy way out

The narratives from the people in these communities all stress how difficult it was for them to leave. Apart from the sentimental attachment to the land and the availability of farms to sustain them in these places, Boko Haram terrorists also actively prevented them from migrating. They blocked the exits and erected tall, thorned fences around some communities, leaving only two entrances/exits. They attacked those they found trying to escape. “This is the daulat,” they would say. “You cannot leave.” They would rob whoever they caught of their valuables or even kill them. According to someone from Zawara, a community in Marte, the insurgents were so paranoid about people leaving that they would chase after flashlights that came on at night, thinking they might be held by those sneaking away, or come in the morning to level accusations and beat people up.

There are various reasons for this paranoia. Aside from the fact that you cannot have a caliphate without subjects, the presence of people in these areas also served as a cover against military offensives.

When Abba Konto finally left Bogomari last year, it was because he saw a rare opportunity.

“When there is chaos among them, we will seize the opportunity to run. Even now, they are killing themselves; the factions of Mamman Nur and Shekau are fighting among them,” he explained.

Since Boko Haram’s top commander, Abubakar Shekau, died in May 2021, and his Sambisa forest stronghold fell to the rival terror group, ISWAP, there have been frequent clashes between fighters loyal to the two groups. This distraction has made it possible for captives and subjects in terror group-governed areas to escape.

Military onslaughts have also created windows for escape in the past.

The dangers of leaving the rural areas for displacement camps or host communities in garrison towns come from both sides of the war. The indiscriminate arrests and indefinite detention of people relocating from these communities by the Nigerian Army are well-documented.

It was like being trapped between two fires, Dukje Ali, 54, said as he described life on the front lines. He lost children to both warring factions. About a decade ago, in Gaje, where he is originally from, Boko Haram killed the community head and his son — 12-year-old Awali, who died from a gunshot to his leg. In 2021, following a military onslaught that bathed the village in fire, he relocated to Yagana Ali, another village within the sphere of Boko Haram’s control about 20 kilometres away, where he made a makeshift tent under a tree. A year and a half later, in June 2023, around 8 in the morning, the military attacked Yagana Ali and killed lots of terrorists. But four civilians also lost their lives, including Dukje’s 23-year-old daughter, Aisa, and some of his neighbour’s children who were shot while running.

When the operation ended that afternoon, all everyone could think about was how to flee to safety. They did not waste time grieving or burying the dead.

“We just left them to God. We seized the opportunity and left the village. If we stayed, Boko Haram would come back and stop us from leaving,” Dukje explained, his voice soft and solemn.

He remembers leaving behind four of his cows, six bags of beans, and six bags of millet. More than anything, he still feels bad about leaving Aisa’s body to rot without a proper burial, but says it was a decision he had to make to protect the rest of his family.

“We left Wulte because of the loss. We have lost all our wealth; we don’t have food and shelter. When you run and come back, everything is burned. All our livestock had finished.”

– Mallam Musa Modu

Unlawful and unacceptable

Arson, even during conflict, violates both local and international laws.

Nigeria’s Armed Forces Act prohibits officers from setting fire to dwelling houses, adding that those found guilty through a court martial are to be imprisoned for life. During the civil war of the 1960s, some of the orders given to federal forces were that they could not maliciously destroy buildings and properties and they could not loot. Nigeria’s military manual similarly prohibits the “attack, destruction, removal of objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population”.

Additionally, the forcible removal of civilians from their communities is considered a war crime under international humanitarian law. The Geneva Convention provides that warring parties “may not order the displacement of the civilian population … unless the security of the civilians involved or imperative military reasons so demand”.

Most of the people who talked to HumAngle said the soldiers did not address them during the raids, so they could not say for certain why they did what they did. But it seemed what they wanted was for them to abandon their homes. “We left because they killed us and because they burned our foodstuff. We left because we couldn’t get anything to eat,” said Zaram.

The intention of the Army was occasionally made clear when the officers got involved in evacuating the villagers, such as what happened in Awada in 2014, in Ziye in 2015, and in Bukarti and Matiri in 2020.

A high-ranking officer of the Nigerian Army who has been involved in counterinsurgency operations in many parts of Borno for over six years described setting fire to civilian settlements as ‘totally unacceptable’. Ideally, soldiers would only burn down villages after confirming them to be harbouring terrorist camps or cells. But he admitted there are times when other factors come into play.

“Most of the villagers are involved in aiding the terrorists with intel and also serve as hideouts for them,” said the officer who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “Several times, soldiers were ambushed in such villages, and this led to grievances. When a soldier remembers how his fellow fighter fell down, this will create more anger and might lead to burning down villages and communities, but a good commander would not allow such.”

He added that he has personally discouraged the act because it causes communities to lose confidence in soldiers, which makes fighting insurgents harder because the military, in turn, loses access to vital intelligence.

“In most cases, when such communities involved in aiding terrorists are burned down, you notice fewer attacks within the territories, but it is not a positive or effective approach to combating the spread of terrorism.”

He stressed that no commanding officer would sanction the burning of civilian houses, and soldiers who are caught are severely punished. He also confirmed to be privy to one case in northern Borno of a soldier who looted livestock from a community. He said the soldier was deranked, asked to return the money from the sales of the animals to the community, and was given extra duties as punishment.

“Most of the junior soldiers don’t know the international implications of burning down a community during operations. It is the responsibility of the commanding officers to coordinate and inform their soldiers of the laws guiding operations and war crimes,” the officer said.

Chidi, the security analyst, emphasises that the rule of law must always be adhered to even during conflict and suggests “straightforward police work” as a more logical response in murky war situations.

“Interview local people, but treat them decently. If the population is hostile or there are armed groups in the area, they can be removed temporarily for their own protection but also to prevent them from supporting or concealing the enemy.”

Zara has not been to Awada since the attacks. Three years ago, she left Maiduguri for Ajiri, which is closer to her home but isn’t the same.

“Nothing feels normal anymore,” she said, not after watching soldiers swoop into your community and kill your loved ones. But then she added, “God had destined it to happen. Even if it is not okay, it is okay since it is God’s doing.”

She may not know why it happened, why both the husband who anchored her feet and the house that shielded her head in a way no other place could were taken from her on the same day. But she remembers because memories are not flammable, not even tragic ones.

Zara Goni remembers.

GIS/OSINT research and visualisation by Mansir Muhammed.

This reporting was completed with the support of the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID) and the Open Society Foundations.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter