Knifar: Separated By Military, A Borno Couple’s Uphill Journey Back To Each Other

Both were sent off to two death zones, the husband to the Giwa military barracks and the wife to the Bama Hospital IDP camp. Luckily, after several years, they made it out alive to tell their stories of adversity and resilience.

‘The women cannot farm, or go to fetch water and firewood. And when the men harvest, they must pay levies. From 50 kg of produce, they will give us 15 kg during the seasonal farming season. During the dry season, we shall receive 10 kg out of every 40 kg of produce. Not to forget, everyone must also attend our Qur’anic classes.’

Locals say those were some of the rules imposed by Boko Haram militants six years ago after they invaded Ziye, a town in the outskirts of Borno State’s Bama Local Government Area. They had seized Bama the previous year. By Nov. 2014, the towns of Gwoza and Chibok in Borno, Mubi in Adamawa, and several others had also fallen under the terror group’s control.

The following March, over six months after the daring attacks, the Nigerian military finally recaptured Bama—but not fully. Many of the terrorists simply escaped to the suburbs which comprised communities like Ziye. This was when the young couple, Bulama and Jugudum Modu, had their first encounter with Boko Haram.

Because it is a small, obscure village, residents of Ziye usually prefer to associate with the nearby ward of Darajamal. It is in the southern part of Borno, almost sharing boundaries with Adamawa, and had a population of a few hundred people.

Townsmen cultivated onions, garden eggs and other choice vegetables, and the women busied themselves with fetching firewood from nearby forests and water to prepare meals. But, when the insurgents declared the village part of their “caliphate,” life as they used to know it turned on its head. Women could not move freely. Not only did the villagers feel trapped, but they were prevented from leaving. A few militants were assigned to the community while many more settled in the surrounding villages.

Seeing how they had to let go of a huge portion of their harvests to stay alive, Bulama soon ran out of patience and found a way to travel to Lagos, a state in southwest Nigeria nearly 800 miles away. He spent five months in Lekki Phase One as a security guard and maintained contact with his family.

“One Saturday evening, they called to tell me my father was ill. Then I said, ‘But I spoke with him today. Just tell me he is dead.’ I called another person who said they [soldiers] shot him dead at 5:40 pm while returning from Kirawa market at the border with Cameroon,” he recounts in Hausa.

He immediately informed his employer, gathered his belongings and returned home through the Abuja-Jos-Yola route. From Yola, he travelled to Mokolo and then Kolofata, both Cameroonian towns. He then re-entered Nigeria through the border to avoid getting accosted by either military personnel or insurgents.

Three days after his arrival, the insurgents visited him and threatened to seize his properties for sneaking away to visit the “place of infidels”. That was not the last he heard from them. Weeks later, six gun-toting Boko Haram members returned. They would kill him if he did not renounce the title of Bulama, they growled.

Bulama is a name traditionally given to the ward head who reports to the village head, known as Lawan. The Lawan in turn answers to the district head ‘Aja’. Bulama’s father was ward head until his death and the saddle had fallen on him. But to save his own life from the terrorists, who only recognised leaders they themselves appointed and accused everyone else of treason, he had to let go of the post.

Months went by and reports started trickling in of military advances. First, in Sept. 2015, soldiers recaptured the town of Banki, famously causing about 200 members of the terror group to surrender. About three months later, they stormed Darajamal. In the second week of December that year, the military offensive reached Ziye.

The villagers were gathered and taken to Darajamalㅡtheir community set on fire and reduced to ashes behind them. It was the first sign they would be displaced, detached from the only home they had known, for a very long time. And all they had with them were their clothes and utensils.

From Darajamal, still packed in four military trucks, they went further to Bama, which had started to take shape as a fortified garrison town. The area was protected against terrorist attacks both by officers of the Nigerian Army and members of a vigilante group formed back in 2013, the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF).

All of the villagers were taken to a prison in Bama. The next day, the soldiers separated them into two groups and the women were taken to the Bama General Hospital Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camp.

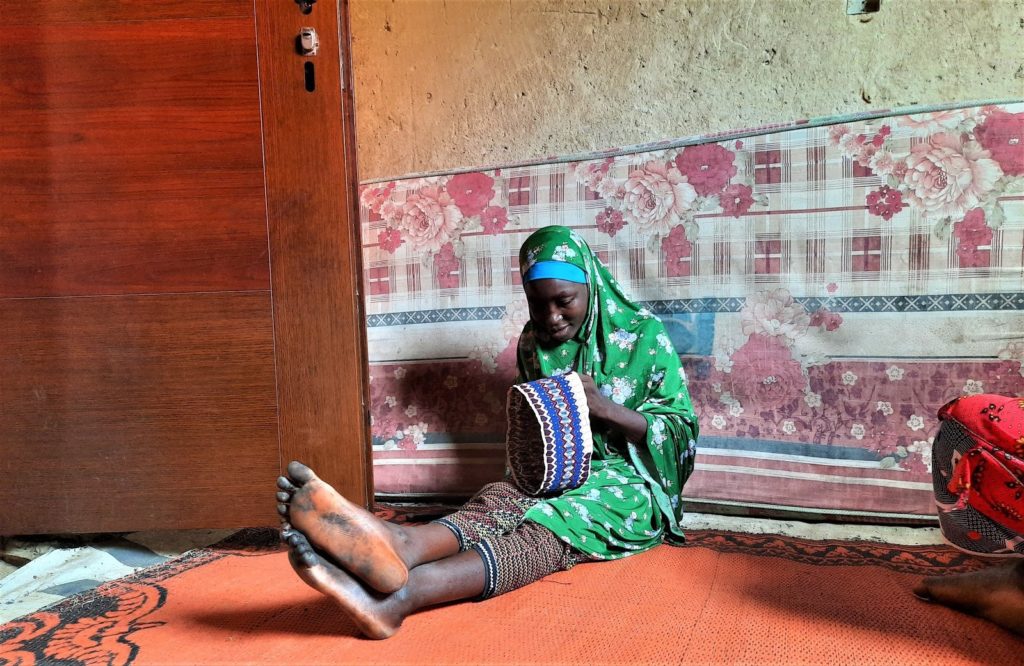

“We waited and waited for our men, but they didn’t come,” 20-year-old Jugudum says. It was later she found out they had been taken to the notorious Giwa Barracks.

*

Bulama spent about five nights at the Bama Prison, a longer period than his wife had. The military interrogated the men to find out if they had joined Boko Haram. They denied the allegation. “Truly we stayed with them,” they had explained. “We see them moving around. They come and pass. They seized our properties and even stopped our wives from working. But we did not join.”

But their pleas fell on deaf ears. In between biting strokes of corporal punishment, the soldiers insisted they must have pledged allegiance to the terrorists since they did not flee after their community’s invasion. Two days later, they transferred them to Giwa Barracks, a military detention centre in Maiduguri, Borno state capital.

Amnesty International, a research and advocacy group, had in 2016 described the barracks as a “place of death” and recommended its closure. The non-profit noted that in the first four months of that year alone, at least 149 detainees had died due to starvation, dehydration, and disease.

The group said mass arrests by the Nigerian military, especially from March 2015, were partly responsible for the overcrowding of the cells. It cited “several instances of mass arrests of hundreds of young men who fled to the safety of recaptured towns, including Banki and Bama, Borno state, in 2016”. The arrests, it added, were mostly based on random profiling rather than any serious suspicion of guilt. Many of the men, like Bulama, were in fact as much victims of Boko Haram’s wars as anyone else.

Bulamas are well respected in many hamlets in Northern Nigeria. They coordinate affairs in settlements, settle disputes, and prevent crises from erupting. In contrast, at the detention facility, he was pushed to the bottom of the social ladder. The Lawan of Darajamal did not fare any better as he was also thrown into the cell like a common criminal.

Twenty-one men from Ziye were taken to the facility. According to Bulama, six died while he was there, including his cousin Duppe Lawan. Ten were released around the same time as him, leaving five men in the cells.

Bulama spent his early days in Cell One. Then, at various times, he was moved to Cells Three, Four, Five, and Seven. There were about 70 inmates in the first cell, rendering it extremely cramped.

“It was not possible for us to lie down. At most, we could only sit,” he describes the cell’s conditions, unfolding his feet to demonstrate the luxury he did not have. He sighs and shakes his head briefly before adding, “It took about two months before we got water to take our bath. You could not get up to a cup of water in a day. Insects and lice were everywhere. It was difficult to survive.”

The inmates ate twice a day, in the morning and evening. People died and were killedㅡ“in a day, sometimes one person, sometimes two people and, if we were lucky, sometimes nobody would die.”

Each cell had a leader known as ‘chairman’. Whether the conditions of a cell would be a bit bearable or downright horrible turned on the whims of this person, himself another detained civilian but chosen by the military personnel. The cell chairman got bigger food portions and had access to water. He assigned ‘bed spaces’ and, unlike others, had room to stretch when it was time for sleep. He often bathed twice a day too.

To keep other inmates in line, the chairmen employed all kinds of cruel tactics. They beat them and forced some of them to drink urine. One of the cell leaders was especially savage. They called him Lagos. He was at different times chairman of Cells Four and Five. Lagos was notorious for slamming people’s heads against the wall and killing “many” in this manner.

Bulama is not sure how many detainees lost their lives while he was in the various cells. Sometimes up to 15 and when he was in Cell Five, the death toll, he says, was over 20.

It did not help that whenever a detainee fell sick, the chairmen would usually prevent them from going to see the detention facility’s medical practitioner. When they did, the doctor would only offer them about two tablets, unless the illness was severe and required admission.

As harrowing as his daily experiences were, one day stood out for Bulama. It was a Wednesday morning. He had become terribly malnourished and could hardly move. Officials of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), a humanitarian organisation, visited the facility, bearing supplies. They requested that the detainees be allowed to have their bath.

“So they opened a tap outside and asked us to wash. I managed to get there. I could not even stand straight. I poured water on myself and before I could finish they started flogging me. I was sick. I could not run … I will never forget,” he says.

Throughout his stay at Giwa Barracks, Bulama never stepped foot outside the facility and was not allowed to communicate with his family, though this violated international humanitarian law. According to the 1949 Geneva Conventions, which have been ratified by Nigeria, even prisoners of war must always be treated humanely and allowed to send and receive letters.

The law further states: “Immediately upon capture, or not more than one week after arrival at a camp … likewise in case of sickness or transfer to hospital or to another camp, every prisoner of war shall be enabled to write … informing his relatives of his capture, address and state of health.”

But the Nigerian Army does not own up to any wrongdoing. Last year, former army spokesman Sagir Musa said there was no basis for allegations of torture and unlawful detention at Giwa Barracks. “The Nigerian army has strongly debunked such malicious claims and no group has convincingly refuted our position,” he told The Guardian.

Seeing as no one had been released years into his detention, Bulama had lost hope of ever regaining freedomㅡuntil a week-long hunger strike took place sometime in 2019.

“At that time, they were not serving any soup along with the food, so we refused to eat and said we would rather die. The food was left outside and it spoilt. This happened about three times. Then one military general came and said, ‘I am your Muslim brother. You should be patient. I can tell you, some of you would be released.’”

Not long after this episode, in November, 983 detainees, including Bulama, were discharged after they had “been cleared of any wrongdoing”—the largest of such releases since the insurgency started.

Bulama has a knack for memorising dates. He remembers, for instance, the day soldiers poured into his hometown: Monday, Dec. 7, 2015. Or the evening he was matched in handcuffs to Giwa Barracks: Sunday, Dec. 13, 2015. More fondly, he remembers the Wednesday he was released four years later: Nov. 27, 2019.

Through those four agonising years, he missed his family sorely. He constantly wondered if his wife, children, and mother were doing alright and yearned to see them again. Jugudum and the children, as he would later find out, were anything but fine.

*

The stench of death pervaded the air at the Bama Hospital IDP camp. Children wailed often, their cries weak from having too little to eat. Their mothers looked on helplessly or tried for the umpteenth to console them. They were used to a life of plenty in which they farmed all sorts of crops and vegetables. But, now when they dug the soil, it was to bury a loved one. No bountiful harvest lingered in the days ahead, except of sad memories and more tears.

Jugudum had four children. She also had to fend for six others—five children who belonged to her in-law and a young boy, Akwigui, whose mother was rumoured to have fled to Cameroon and father suspected to have been killed by the neighbouring country’s soldiers.

“There was no food. We were just suffering at that time,” she says.

A CJTF official who hailed from the garrison town, Banga (first name withdrawn), repeatedly supplied her with maize grits, flour, and rice—which she suspects were stolen food items from donor organisations. He also gave her money to meet basic needs. She guesses he must have been in his early thirties. Asides her petty cap-knitting business, for many months Banga was her only source of sustenance. But he was no philanthropist. Jugudum soon became pregnant with his child after months-long sexual relations.

Amnesty International noted that, between Oct. 2015 and June 2016, at least 879 people died at the camp due to starvation and sickness—with IDPs reporting up to 15 to 30 deaths a day.

This estimate is supported by a press statement released by international humanitarian group Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) following its visit to the camp in June 2016. The medical team reported counting 1,233 graves dug near the camp, among which 480 were for children.

“New graves are appearing on a daily basis,” the group stated. “We were told on certain days more than 30 people were dying due to hunger and illness.”

One of the many fatalities in Bama was Jugudum’s three-year-old son. Banga’s daughter also died six months after she birthed her in 2016. “She fell sick and died of malnutrition. We took her to an MSF clinic. We were given some drugs but she later died,” she narrates the sad experience.

Having extramarital affairs was not taken lightly by Jugudum’s in-laws. It did not matter that she was only trying to survive and prevent her kids from dying. “They didn’t say anything to me. But they talked about it when I was not around. They said I had given birth for another man and I had to marry him,” she says. They also seized two of her children and ostracised her.

Amid all her troubles, Jugudum says she thought about her husband always. Even if she tried not to, the children asked endlessly about their father. She would reply as convincingly as she could that he had gone to Maiduguri and would soon be back.

Rumours started spreading in 2019 about a planned release of detainees, but she did not know if they were true. Then, December came.

*

Bulama was not released immediately. First, the detainees were taken to a rehabilitation centre in Maiduguri commonly referred to as ‘Umaru Shehu’. Jugudum received the pleasant news but was surprised her husband did not call to inform her. So, she resolved not to visit the centre. When a friend finally convinced her to go, she was not allowed to enter.

“We heard people were released and they were in Umaru Shehu. I was not around, I was in Bama. Then he phoned his brother. I was annoyed he didn’t call me after two weeks. I didn’t know why,” she narrates.

“Later, I received a call. When I asked who was speaking, he said, ‘I am Modu Bama, your husband.’ I was surprised and asked why he did not call me since. He said it was a surprise call and then my mind cooled down.”

She visited the facility again when Bulama was scheduled to be released. It was for the two of them a breath-taking moment. “We happily embraced each other and started crying. Then he said, ‘I want to go to Bama with my wife,’” Jugudum recalls. He also asked her to be patient as she had been prior to his release.

Describing the event of that day minutes later, Bulama says he felt as if he were in paradise.

They both proceeded to the Kofa displacement camp in Maiduguri but were prevented from entering because Bulama had not been cleared. He stayed under a tree outside the camp for 19 days. Jugudum, who was admitted, cooked and took food to him during the day. Close to sunset, she would return to the camp while Bulama found somewhere safer to pass the night.

He later obtained a national identity card and travelled to Bama with his wife. After one month, they learnt the displacement camps were admitting new people, so they went back to Maiduguri and settled in the Dalori II camp.

Back together, the two lovers have had a lot of time to talk. And a lot of time to take the first steps towards healing. Bulama spoke of his ordeal at Giwa Barracks: the overcrowded rooms, the difficulty sleeping, and the starvation. He now says he tries not to cast his mind back to those days. Jugudum shared how two of her children, including one of his, died, and how her body became home to a stranger in his absence. She mentioned to Bulama the scorn she had to put up with from their relatives. She painted pictures of severely malnourished children and spoke about the government’s inaction for the longest time.

About the affair with Banga, Bulama replied that he had forgiven her and that the tragic episodes were their destiny.

But the couple’s problems are far from over. They still face abject poverty and food shortages. “It has been over eight months since I was released from Giwa Barracks and I have not received any support from the government,” Bulama says.

He and the rest of the family depend on Jugudum for their daily meals. Every month, she gets food allowances worth N17,000. Both of them additionally knit caps to support themselves and the children.

“We are happy and we understand each other. Our only problem is the food. We all depend on my card,” Jugudum says. She asks that the government also release the husbands of her friends who are still in detention since 2015.

Thousands of women in the state formed an advocacy group in 2017, the Knifar Movement, for this reason: pressuring the Nigerian military to release their spouses from detention. Unlike Jugudum, many other members still wait with bated breath for news about their children’s fathers.

Jugudum does not think it is a good idea to return to Ziye, especially since the security situation has not improved. “But we can stay anywhere if we can get what we need,” she adds.

Bulama, on the other hand, does not care for traditional titles or wealth or even his lost properties. “All I want is for us to live in peace,” he says calmly. And if necessary, he might travel southwards to Lagos again to make ends meet. He already speaks enough pidgin English to fit in easily. But, above all, he would rather have his old, quiet life back, where he did not have to watch his back for insurgents or those employed to wrestle them.

This investigative report is a partnership between the African Transitional Justice Legacy Fund and HumAngle Media under the ‘Mediating Transitional Justice Efforts in North-East’ project.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter