The Bloodbath (4): Nigerians Jailed After Zaria Massacre Share Their Ordeal

Many people arrested during the 2015 mass slaughter in Kaduna, Northwest Nigeria, spent years in prison without conviction, changing their lives forever.

After surviving a fire incident during the Zaria Massacre of Dec. 2015, Ahmad Musa was immediately arrested by soldiers who asked if he was a member of the Islamic Movement of Nigeria (IMN).

“I answered affirmatively and that began my journey to prison,” he said. “The soldiers beat me up, threw me in their van, and claimed that they’d arrested an assistant to Ibrahim El-Zakzaky.”

From the point of arrest, he was driven to the state’s police criminal investigative department alongside over 50 members of the movement.

“By then, all my body had swollen as a result of the injury I sustained from the burns and I was taken to the police hospital. Five days later, we were all taken to Kaduna Central Correctional Centre.”

Prolonged detention violates fundamental rights guaranteed by Nigeria’s laws, which provide that a person may be detained for no longer than two days. A person should only be held for a longer period in line with a court’s directive.

In the case of the arrested IMN members, the police detained them for five days without arraignment before a court. They were then taken to prison, again without a court pronouncement.

“The comptroller of prison first asked for a court order but after speaking with one of the army chiefs on phone, they admitted us into the prison on Friday evening, Dec. 18, 2015. There were over 100 people that were taken there but 16 people, including me, were seriously wounded and we were admitted to the prison hospital.”

The neglect

The arrested individuals told HumAngle that the police attempted to arraign them on Monday, Dec. 21, by bringing a Magistrate to the prison but he declined, claiming he had no official power to adjudicate on the murder allegations levied against the IMN members.

They were then left to rot in detention for several months. Ahmad said he spent five months in prison without appearing in court. The injuries he sustained from the fire incident got healed at this time.

“The prison warden told other inmates that we were more dangerous than Boko Haram and they should treat us as such. It was the worst form of molestation I ever experienced. Trust me, prison is not a good place to be,” he cried.

The refusal of the security personnel to arraign the suspects within the lawfully stipulated time is one of the factors contributing to overcrowding in Nigeria’s correctional centres.

Data from the correctional authority reveals that the country’s facilities have the capacity to hold 50,083 inmates but they currently have up to 70,056. Of these, 50,822 are awaiting trial and only 19,234 (27.5 per cent) have been convicted.

The poor administration of the justice system has become a burden for the country and recent attacks on correctional facilities and jailbreaks place the system under more scrutiny.

The arraignment, ordeal

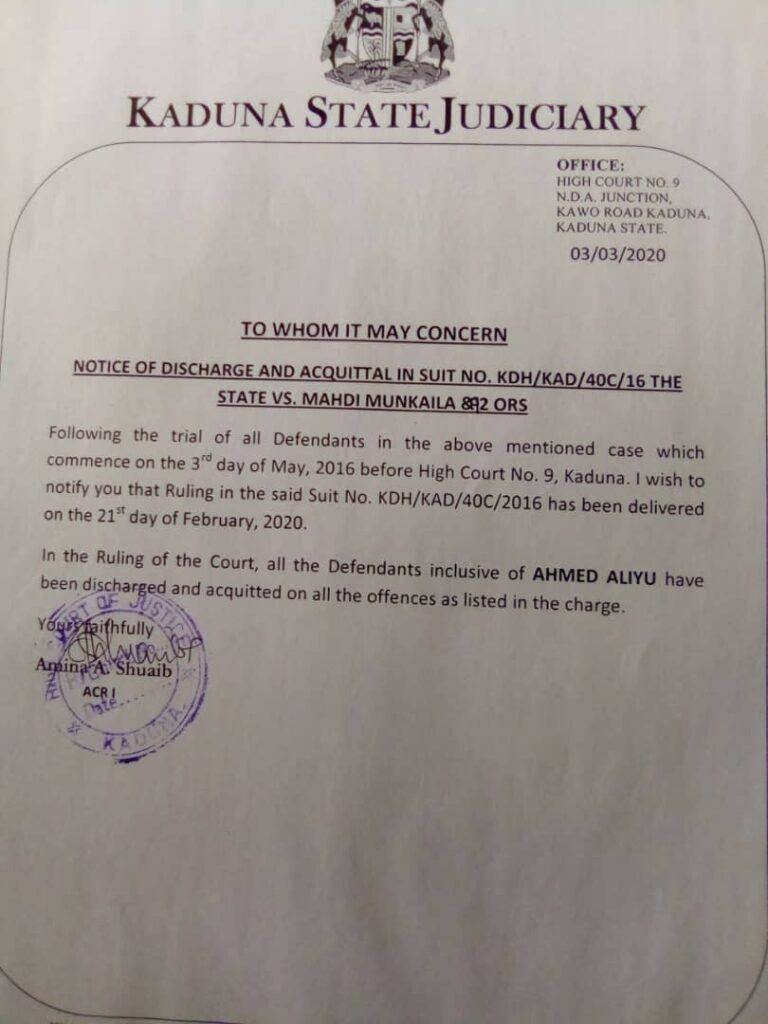

In May 2016, the inmates who were awaiting trial in connection to the Zaria massacre were divided into two groups. While some were taken to Court 4, others were taken to Court 9 of the Kaduna State High Court. They got legal representatives from their movement.

Ahmad who was charged alongside 92 others on May 3, 2016, said, “It was a terrible thing to remember because my two wives and 11 children suffered in my absence. They survived on donations from family members and well-wishers. It was really difficult for them to cope with the breadwinners.”

For four years, he was in an overcrowded cell, which he said led to psychological and emotional trauma for him.

He was eventually discharged and acquitted alongside those in his batch on Feb. 21, 2020. Ahmad, who now works as a full-time Arabic teacher, said he returned to his office in Kano to inform them about his freedom and ask about possible resumption but was told there was ‘no vacancy’.

‘It was divine grace’

Mansur Aliyu’s son, Kabir, had just completed his Higher National Diploma (HND) education and was preparing to register for the one year compulsory National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) scheme when the Zaria massacre happened.

“We thought he was killed because we didn’t hear from him. I went to the hospital and I was told they brought 136 corpses. I tried looking for my son but didn’t find him. It was two days later that somebody called that they were together in police custody.”

He landed in prison from the police detention where he spent four years. He was also discharged in Feb. 2020. Kabir, according to his father, is currently participating in the NYSC programme in Abuja, over six years after he was originally scheduled to.

‘I lost my mum because of my arrest’

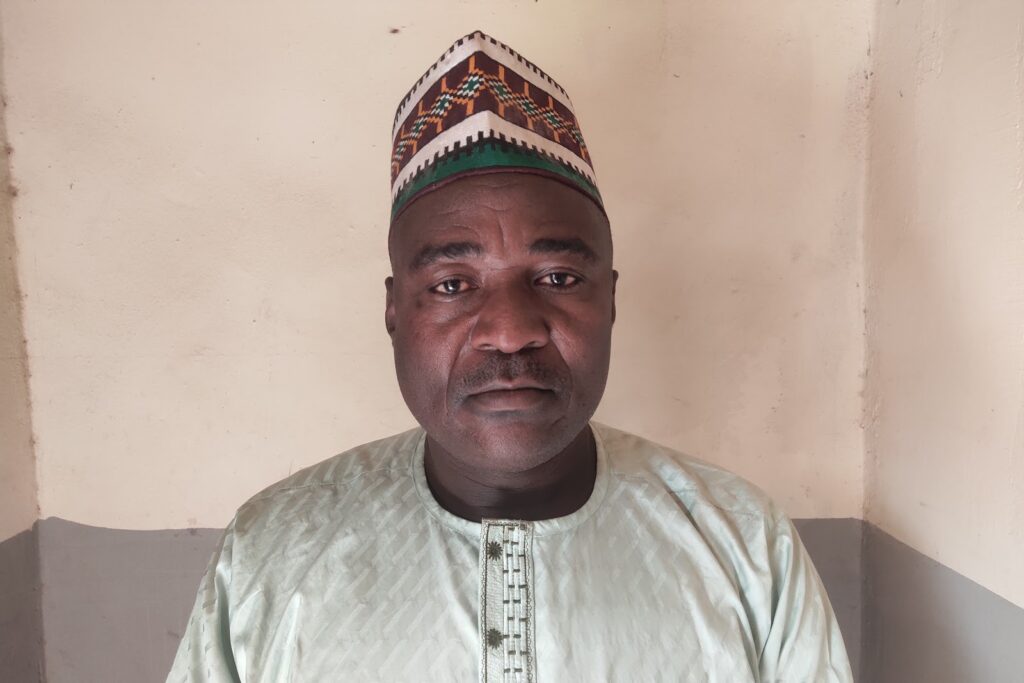

Ibrahim Yusuf, fondly called ‘Coach’ by his friends, was working as a Physical and Health Education (PHE) teacher at the NNPC staff school in Kaduna before the 2015 incident. He told HumAngle he lost his mother as a result of the predicament.

“The school where I was teaching vacated on Friday and I was prepared for the IMN programme. We later got information about the soldiers’ invasion and, after a while, they started shooting.”

He said he hid in the ceiling of a nearby house at the place of the incident with three other people for four days to avoid getting killed.

“We hid ourselves in the ceiling of a house on Saturday when we were running for safety. One of us saw a man-hole in the room and we quickly ran there. The soldiers came there but didn’t suspect that people could be in the ceiling.

“We had an old man who was coughing and claimed he had diabetes. He was coughing and we threatened to kill him ourselves before he exposed us. Sadly, he eventually died of hunger.”

Ibrahim said one of them was able to call his friend, Dauda, three days later that they were hiding in the roof. The police were briefed about their hideout.

“The soldiers were surprised when we eventually came down. The police took us to their headquarters. I got a phone to call my wife that I was still alive.”

From the police headquarters, Ibrahim and others were driven to prison but, luckily for him, the assistant controller was his classmate in secondary school.

“He made life in prison a bit fair for me. I was in prison for one and a half years. I got bail on a medical condition in early 2018 and my mother died three weeks later due to depression triggered by my imprisonment.”

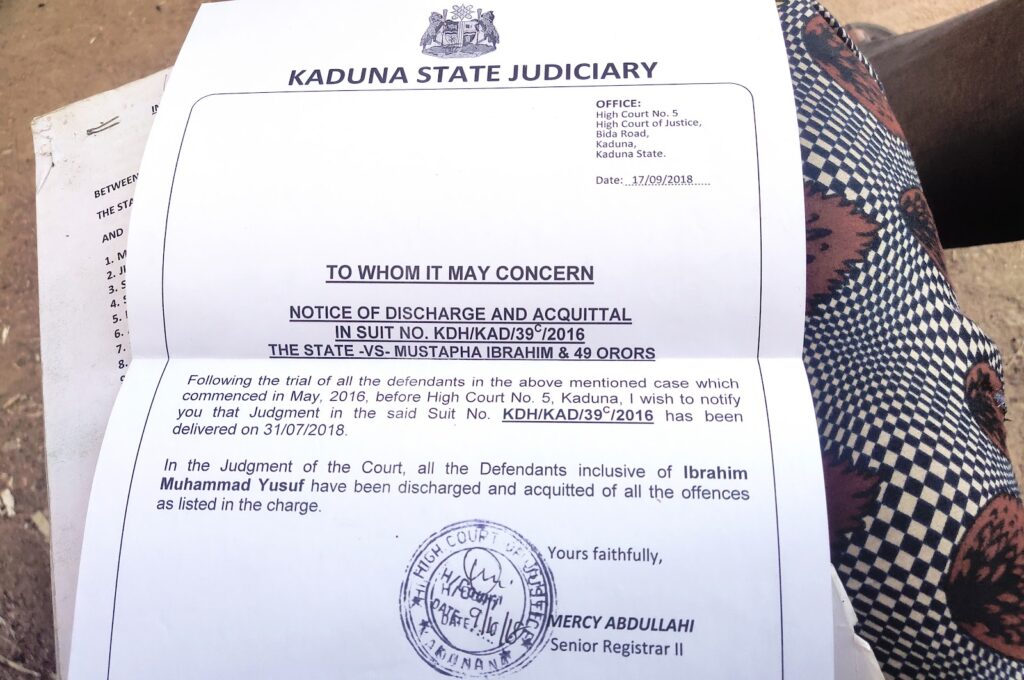

The court would later discharge and acquit Ibrahim and 49 others charged in his batch on July 31, 2018. He has since been jobless.

Justice remains elusive

Even though the Judicial Panel of Inquiry set up by the Kaduna State government indicted the military, nobody has been been arrested, investigated, or punished for the series of human rights abuses.

Our reporter reached out to the office of the Attorney-General and Commissioner of Justice in Kaduna, Aisha Dikko, but did not respond to enquiries about the prospects of justice for victims.

HumAngle also contacted the spokesperson of the Nigerian Army, Onyema Nwachukwu, for comments on the 2015 extrajudicial killings and assaults on IMN members but he did not respond to repeated calls and texts. He also did not respond to enquiries on efforts in place to prevent recurrences.

“It is sad that this is happening in a democratic country. We cannot discuss democracy without justice. The government must find an end to the continued suffering of the victims and their families,” observed lawyer and human rights activist Bimbo Ajayi.

This is the fourth and last part of our series on the 2015 Zaria massacre. You can read the first, second, and third parts here.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter