Seeking Food From A Shark’s Mouth And Crowdfunding Your Way Out

To escape starvation, IDPs in Nigeria turn to farmlands in areas within the grasp of terrorists. To escape terrorism, they turn to their townsfolk.

How do you get ransom from a person who has nothing?

One, you kidnap many people at once. Two, you don’t ask for too much. Three, you hope the abduction is gobbled up by headlines so that people in the government, out of embarrassment, or philanthropists, out of pity, donate to the victims’ families, who then use this to secure their freedom. If that doesn’t happen, you can count on the power of community: the families may not have any money either, but their townspeople should definitely come to their aid.

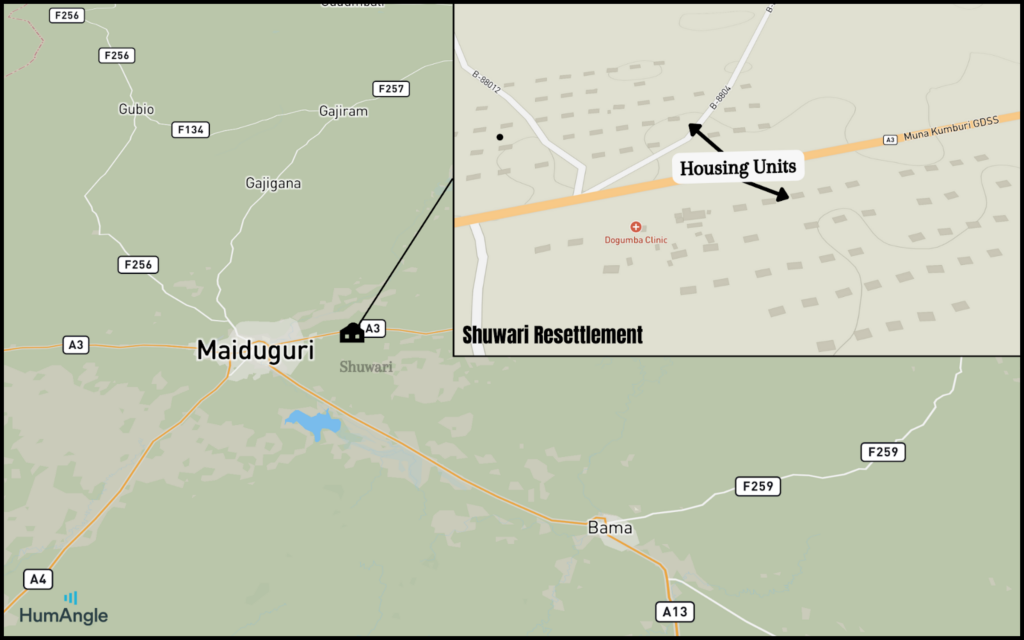

This is the formula now adopted by terrorists in Borno, northeastern Nigeria. Their victims are usually people displaced by the protracted Boko Haram insurgency in the region. Many of them are people whose displacement camps were recently shut down by the state authorities. The government moved them out of the capital city of Maiduguri to sites in other local government areas. They have stopped receiving regular humanitarian aid and are forced to fend for themselves. Since the only livelihood many of them know is tied to agriculture, they look to farmlands for sustenance. But available farmlands are only abundant in remote areas, and remote areas are to Boko Haram terrorists what cracks are to lizards.

Terrorists suspected to be members of the Boko Haram faction known as Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’adati wal-Jihad (JAS) stalk IDPs as they cross into the woods, seeing them as easy targets. They then abduct them and demand ransoms per head that can be raised within a few days.

Many of these abductions go unreported in mainstream media. But in August 2023, one drew the attention of both local and international outlets. Boko Haram terrorists kidnapped 48 women who had gone in search of sustenance in the Jere area of Borno.

HumAngle spoke to five of the victims whose experiences reflect the impossible situation IDPs in the state currently face.

The women had gone to the bush near Shuwari village to fetch firewood, which they would sell to raise money for food in addition to using it themselves as cooking fuel. They started hearing voices behind a tree. Someone was making a phone call. One woman wondered aloud who it was. Others said perhaps the people also came to gather firewood. About four minutes later, they realised they were wrong. Six thundering motorcycles surrounded them.

There were eight Boko Haram members, all of them quite young, some even teenagers below 17 years. Four carried guns. The others wielded machetes. They threatened to shoot anyone who attempted to flee. Then they marched them further away from town, sometimes barking orders to walk faster with lashes on the back.

“They kept threatening us and saying that our husbands let us go into the bush because they didn’t care for us. ‘You are unbelievers, wandering, going for firewood. It is not your duty,’ they said. We told them that our husbands are also fearing they will be kidnapped,” Yagana Grema, 30, said.

The terrorists said they would have to pay ₦100,000 ($104) each if they desired to be free again. The women explained that they did not have any money and they had even gone to fetch firewood so they could afford food. Grema said some of them had not been able to buy guinea corn in three weeks and had resorted to eating biri gamda, a form of leftover usually reserved for livestock. The women also shared their concerns for their children, who must be starving and worried sick. But their pleas fell on deaf ears.

“They said they didn’t care, and we had to pay if we wanted to be released. We should not quarrel with them,” Grema recalled. “They kept saying that unless we brought money, they would kill us like animals.”

One woman complained about the orphaned children she left behind. The terrorists’ reply? That there are no orphans among infidels. “Let them die.”

Eventually, when they reached a settlement, they called people back at the Shuwari resettlement camp with their demands. They had initially released two women to notify people in town about what had happened and give them a number to call. The following day, they released nine elderly women. Four others managed to escape after excusing themselves to answer the call of nature.

In the evening, they continued their trek and camped at another place. The terrorists provided mats and mosquito nets. After some people brought food for them, they prepared rice for their captives and offered them water, but most of the women had lost their appetite. If they tried to stand and stretch, the terrorists would beat them and order them to sit. At night, it seemed they had a roster. While some of them slept, others stayed awake, their eyes pinned in the women’s direction.

Where they camped is estimated to be over 30 kilometres from the Muna IDP camp in Jere. Another woman estimated that they must have trekked for over 50 kilometres, getting to a place close to Bama.

It was only when they were released two days later that the women learnt their abduction had received press coverage. They also did not know the details of the ransom negotiation. Isa Kamsulum, one of the IDPs at the Shuwari site, told HumAngle the terrorists first demanded ₦2 million ($2,088). The people protested, explaining that they were even starved of food. The next morning, the abductors agreed to a ransom of ₦20,000 per woman. But they also had to deliver 20 mudu of rice and vegetable oil. The people raised ₦480,000. But when they went without the rice, they detained the go-betweens and insisted on the foodstuff.

The ransom was raised quickly thanks to a ₦1 million donation from a government official who read about the abduction in the news. The official chided the IDPs for not informing them privately. “But would they come if we had told them?” one man at the Muna camp scorned.

Part of the donation was paid to the terrorists, while the rest was shared among the families. If the official had not come, Kamsulum said, they would have had to beg and crowdfund.

“Now, if you go to Muna, a lady came and said they took her two children. They abducted six of them the day before yesterday. She is begging for ₦30,000. You will see her in the market. People are giving her ₦10, ₦20.”

Begging in the market like this woman is one way to go. There’s another.

The saving grace for IDPs who find themselves trapped in the terrorists’ nest is that they can bank on others lending a hand. This works because everyone expects that if they or their loved ones were to get in trouble — which is quite likely, others would do the same for them.

Ahmadu Aga, a community leader at the Muna Elbadawi camp in Jere, says such contributions are more frequent these days. In the past, donation drives were conducted only when someone died and the family did not have a lot on which to survive.

“Because there was peace,” he explained. “People went to their farms and returned safely. The abductions started within the last two years. They started by collecting our food whenever we went to farms. Then they started searching us for valuables such as mobile phones. And later, they started abducting our people.”

The abductions have become so constant that different communities have had to set up committees for ransom-raising. They communicate with kinsmen living in camps in other local government areas and share resources.

“If they say they have taken somebody, the committee in Mafa will call us and tell us what happened. We will ask for updates, and if a demand for ransom is made, everybody will start contributing. If someone is kidnapped here, they will do the same.”

He gave the instance of one health worker whose four children were recently abducted on an onion farm. The terrorists initially asked for ₦2 million but shifted grounds and agreed to ₦400,000. People give whatever they can afford, whether that is ₦50 or ₦100. Eventually, it piles up into something significant.

Ahmadu heads the fund-raising committee for people from Boboshe I, Boboshe II, and Boboshe III, which was created in 2022. The first people to try the organised crowdfunding approach were IDPs in Customs House, a place on the outskirts of Maiduguri along Mafa Road. He explained that Gumshe and other districts in the Dikwa local government area also have their own committees.

Since their displacement about a decade ago, this period has been the worst, according to Ahmadu. Last year alone, as of September, they had raised ransoms for up to 30 people from their community alone.

“There’s too much hunger and starvation,” Ahmadu said.

“You see the man who just passed? He came to beg because he hadn’t eaten in five days. This is the situation. If you go to the farm, you are not secure. If you stay, nothing. People still go because they have nothing to eat.”

Kamsulum explained that support from the government has been almost inexistent for the past three years. “It was only the day before yesterday they gave us 25kg of rice and 25kg of guinea corn,” he said.

The Shuwari resettlement site consists of 1000 housing units. The authorities only assigned rooms to people indigenous to Jere. But people like Kamsulum from other parts of the state said they were instructed to settle there, too, and were assured they would be taken care of. About 350 households in the area live in makeshift tents.

Increasing poverty and hunger among the resettled people have pushed them to adopt desperate survival measures such as risky trips to remote forest areas, which most of them only started doing after their removal from the Bakassi and Farm Centre camps. Another trend is the consumption of animal feed. Many also send their sons to tsangayas (Qur’anic schools), where they would be encouraged to beg residents for meals.

Some of the recently abducted women are single mothers who have to care for six to eight children. Amina Gale’s husband, for example, has been detained by the authorities at the Giwa barracks for the past eight years. Bintu Hassan lost her husband to a suicide bomb attack near Maiduguri’s Bakassi camp in 2016. Those with husbands around say their partners do not earn enough money to fend for the family, so they are forced to complement however they can. After each visit to the forest area to collect firewood, they make an average of ₦500 (half a dollar). But that is only on days they get a buyer for the wood. Sometimes, this does not happen until the next day.

Many of the women used to live at the Bakassi camp, which was shut down by the Borno state government in November 2021. In Bakassi, the national emergency management agency usually distributed rice, beans, and guinea corn among the IDP. The women didn’t have to risk their lives in the forest to get by.

Yagana Kassim, 35, said when the resettlement exercise took place, she wanted to return to Marte, her ancestral home, but was told the ‘list was full’. So, she stayed back. The IDPs received between ₦50,000 and ₦100,000 from the government, depending on their marriage status. Hajja Kawo spent her ₦50,000 on foodstuff and utensils, changed her worn clothes and those of her children, paid a carpenter to rebuild her tent in Shuwari, got a water reservoir, and bought maize with what was left. Bintu Hassan received ₦100,000. She spent it on the same things and said it didn’t last her for long.

The abduction experience has left the women traumatised. They have regained their freedom, but the terrorists still have a grip over them, especially at night when they slip into dreams which seem to lift them back into those fearful episodes in the bush.

A few of the women — like Grema whose husband teaches at an almajiri school — told HumAngle they would not be searching the woods for sustenance anymore. Most replied that they would still brave the odds since they had no other obvious choice.

Since her husband is not around, Amina, for example, has to look after seven children by herself, and they are all still too small to earn a livelihood. She has returned to the remote farmlands since the incident to plant beans for a fee. But it hasn’t been easy. She is not sure what the problem is. “Each time I go to the bush, I will be nervous. Maybe that’s what made me sick, or it is just a fever,” she said. Every morning, after preparing breakfast for her children, she starts to worry and wonder whether she will return to them safely.

Grema summarises the dilemma they all face perfectly:

“We can’t go because of the danger, and yet, we have no option.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter