Nigeria Can Combat Violent Extremism Beyond Military Might. Here’s How

Terrorism and other forms of violence have deeply destabilised different regions of Nigeria and the wider sub-Saharan region

On Feb. 12, the world marks the International Day for the Prevention of Violent Extremism (PVE) as a reminder of the devastating impact of violent extremism. It also speaks to the imperative need for sustained action to curb violence and extremism.

Between 2007 and 2022, the Terrorism Tracker recorded over 66,000 terrorist incidents worldwide, emphasising the cost of violent extremism. In 2021, the scourge is responsible for 48 per cent of the global terrorism deaths in sub-Saharan Africa. These violent incidents have disrupted global commerce, technology, education, climate, governance, and security.

From the Boko Haram insurgency and expansion agenda, the ESN/IPOB separatist group, and the newly emerged Lakurawa terrorists in the northwestern region, terrorism and other forms of violence have deeply destabilised different Nigerian regions and the wider sub-Saharan Africa.

The use of violence to achieve ideological, religious, or political goals has led to the displacement of nearly 2 million people and threatened the economic activities of the population in northeastern Nigeria. Despite over 15 years of military counterterrorism operations, violent extremism persists.

Community susceptibility to violent extremism

The eruption of Boko Haram has prompted scholars, security experts, international organisations, and civic actors to focus on understanding the background of the conflict and the enabling environment that allows the spread of violent extremism. This has contributed to the larger body of knowledge and practice of peacebuilding. Over the years, several push and pull factors have been discovered to tailor communities’ susceptibility to violent extremism.

Governance failure and political grievances are the push factors compelling people feeling marginalised or with historical grievances to accept radical ideologies that eventually lead to violent extremism. Pull factors include the perceived benefits of joining extremist groups, such as the promise of self-authority, a sense of purpose, and economic opportunities.

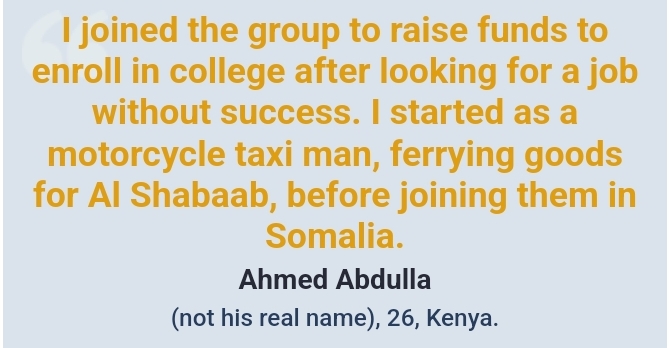

Violent extremism rides on the scarcity of resources exacerbated by climate, inequality, induced poverty, and economic hardship. This allows extremist groups to embed themselves into societies in the Sahel and Sub-Saharan Africa to recruit those grappling with socio-economic stress. Socio-economic factors such as poverty, unemployment, inequality, and illiteracy interact with vulnerability to make communities susceptible to violent extremism.

High unemployment rates also create a vulnerable population with a propensity to be manipulated into chaos and violent extremism. For instance, in Borno State, the epicentre of Boko Haram extremism, there is a poverty rate of 70 per cent higher than the national average. According to a study, this extends to the entire northern region, where there are notably higher levels of poverty, youth restiveness, and income inequality.

It is against this backdrop that it makes sense how violent extremists deliberately target and destroy critical socio-economic infrastructure such as electricity and communications and attack markets and schools. An impact of this would be increased socio-economic instability. In Mali, a Sahelian state with the presence of violent extremism, the Tony Blair Institute study found a 40 per cent increase in water infrastructures attacked by violent extremists simply to gain control of water in the region they operate. This underscores the need for breaking the cycle of socio-economic hardship by underlying factors of poverty, inequality, and unemployment that sustain violent extremism, providing it with a pool of vulnerable and at-risk populations to recruit.

Governments that fail to preserve social justice and service delivery lose credibility. Communities without social justice and government services hinge their trust in whoever is ready to step in with intervention that upsets the lack of governance. They are the ungoverned space.

The ungoverned spaces provide room for non-state actors to exploit the vacuum of governance and build trust between their mission and people. This is true to the conclusion of the UNDP: “There is no better environment for the expansion of violent extremist groups than a vacuum in state authority.”

In 2021, trying to fill this void, HumAngle reported the distribution of petty cash to households in Geidam, Yobe State, by the ISWAP violent extremist group. In another twist, there is an interest in the psychological implications of the aftermath of conflict, yet it is often overlooked how it makes people vulnerable to being lured into recruitment to arms opposition groups.

While the conversation around radicalisation on its own receives adequate attention as a systematic pathway recruits pass through before enlistment into violent extremism, it takes cognitive manipulation to occur, which itself is psychological. The feeling of group-based victimisation is found in numerous studies to drive people into violent extremism; thus, psycho-social variables are key factors. This is understandably why disengagement, deradicalisation, and reintegration processes incorporate psychosocial care for ex-violent extremists.

A 2023 report by UNDP places limited access to jobs ahead of religion and ideological drivers of violent extremism and recommends a shift from purely security-driven to a development-based response of prevention and countering extremism. However, this does not undervalue the role religion continues to play in radicalisation and recruitment. While religion may not be a direct factor, it gives an added layer for justifying violent conduct and as a way to express grievances.

In recognition of their role, religious institutions and actors countered extremist narratives by providing alternative teaching and interventions across the division between the Islamic and Christian faiths in Nigeria. In 2022, a group of Islamic scholars established the Islamic Centre for Peace Building, Research and Development to counter and prevent violent extremism and address other development issues.

Additionally, there is a growing use of digital platforms for propaganda, fundraising, and recruitment into violent extremism, making technology and social media indispensable in violent extremist discourses. Using local language to gather and misinform people, the weak algorism of Facebook to detect local language contents, Al-Qaeda-linked Ansaru al-Muslimina fīy Bilad Sudan operating in Northern Nigeria, has an edge, for instance, in using social media to appeal for sympathy.

Regional instability as a ‘new’ factor?

The political instability in the West African region occasioned by the military takeover in Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso, and the political landscape led to the exit of these countries from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) — a regional block with priority shared on economy, peace, and security.

This fallout in regional cooperation within the ECOWAS member states has created a unique avenue to make border communities and displaced people vulnerable to violent extremist ideologies. The countries under ECOWAS have formed alliances for military and non-kinetic operations to counter violent extremism for stabilisation and humanitarian responses, including the Multinational Joint Task Force.

This regional political fallout is bound to affect cross-border violent extremism, stabilisation, reconstruction, and peacebuilding initiatives, which give violent extremism fertile ground to regrow.

Addressing community susceptibility to violent extremism

Prevention of violent extremism requires a multifaceted approach. Policymakers’ intervention and community-based prevention mechanisms, both the push and pull factors point to one thing: the limit of militarised or kinetic action to end violent extremism.

In 2019, Nigeria’s Army Chief, Lt. General Tukur Yusuf Buratai, expressed the urgent need for diversifying counter-terrorism from purely kinetic into what he calls “spiritual war” to counter the ideologies of violent extremists.

However, experts and policymakers offer the following recommendations to curb violent extremism:

- Expanding access to quality education and counter-narrative programmes that provide alternatives to radicalisation and empowerment. This should address underlying historical, political, and group grievances that will eventually disallow any space for extremism to take a toll.

- Empowering community engagement initiatives from traditional early warning and early response mechanisms to local-led peacebuilding and conflict prevention solutions such as the Tea4Peace. This should prioritise the socio-economic development of the communities and forge collaborative work with government structures at the grassroots, sub-national, and national levels.

- While technology and media are tools for enjoying many rights guaranteed by the constitution, partnering with tech companies, especially Meta and TikTok, will improve the detection of extremist content and online radicalisation. The government should collaborate with civil societies, rights activists, and the media to support efforts at monitoring and exposing the online presence of extremism by empowering communities with knowledge and skills to identify extremist content. It should also support public interest works such as what HumAngle did monitoring terrorist TikTok propaganda.

- Nigeria’s counter-terrorism policy as a well-spelt-out national policy document must align with local realities to be effective. The stakeholders should champion its localisation, especially with the local government autonomy now in place. This involves the policy translation into an actionable working document with deliverables that empower marginalised and vulnerable communities to build enough resilience to violent extremism.

- Strengthening of collective regional peace and security priorities to enhance border surveillance. This will tame cross-border violent extremism, especially from the Sahel down to the Lake Chad region. This is irrespective of whether the states affected have a military or democratic regime in place. The ECOWAS should find a means of restoring democracy that is more diplomatic and will not escalate extremism by undermining close collaboration between the states.

The article by Abdussamad Ahmad Yusuf highlights the pressing issue of violent extremism and its widespread impact.

Despite over 66,000 terrorist incidents recorded globally between 2007 and 2022, violence persists particularly in regions like sub-Saharan Africa, with extremist groups exploiting governance failures and resource scarcity. Socio-economic factors, such as poverty and unemployment, contribute to the susceptibility of communities to extremism.

The failure of effective governance and political instability further exacerbate these vulnerabilities, offering non-state actors opportunities to exploit governance vacuums.

The text stresses the need for a multifaceted approach to counter extremism, incorporating education, technology, and community engagement.

The UNDP suggests a shift from security-driven responses to development-based strategies, encompassing expanded education access and counter-narrative programs.

The strengthening of local governance, collaboration with tech companies to detect extremist content, and the reinforcement of regional peace and security priorities are also recommended.

The role of religion and technology in radicalisation is acknowledged, urging policymakers to integrate spiritual and psychosocial interventions in their strategies.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter