Inside The Propaganda World Of Nigerian Terrorists On Tiktok

With its popularity in Hausa-speaking Northern Nigeria, TikTok has become an unexpectedly powerful weapon in the hands of armed groups who join trends and directly engage people on the platform.

Northwestern Nigeria, long bedevilled by terrorism locally referred to as banditry, now faces an emerging threat: the use of social media platforms, particularly TikTok, by violent non-state actors to spread propaganda, undermine security efforts, and incite violence.

With an internet penetration rate of 45.5 per cent as of 2024, Nigeria has an active number of TikTok users, amounting to 23.84 million. TikTok, initially used for short dance videos and viral musical challenges, has become popular in Hausa-speaking Northern Nigeria and the country as a whole. Its combination of short and engaging videos has captured the imagination of millions, particularly young people seeking entertainment, community, and a sense of identity. TikTok’s algorithm-powered “For You” page has also made it easy for users to receive suggested videos that are trending in their locations or based on their previous likes and watch history. This has made it easier for particular videos to trend within a particular audience or location, creating an echo chamber that reverberates similar messages. For the terrorists in Northern Nigeria, this has presented a great opportunity to spread their propaganda, misinform the public, and recruit followers, leveraging the platform’s loophole to create targeted echo chambers of content that resonate with specific audiences.

Terrorism and rural banditry in Northern Nigeria is not a recent phenomenon. Rooted in historical grievances and exacerbated by poverty, injustice, and poor governance, these criminal activities have evolved from small-scale cattle rustling and local disputes into organised, violent movements.

The armed groups operate under different dabas (gangs) in large forest areas connecting Kaduna, Katsina, Zamfara, Sokoto, and Kebbi states in the northwestern region and Niger state in the north-central region. Their activities have resulted in the death, displacement, and abduction of hundreds of thousands of people.

Copying from the operations of jihadist groups such as Boko Haram and Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), the armed groups have recently refined their tactics, increasingly turning to propaganda to bolster their ranks and spread their messages.

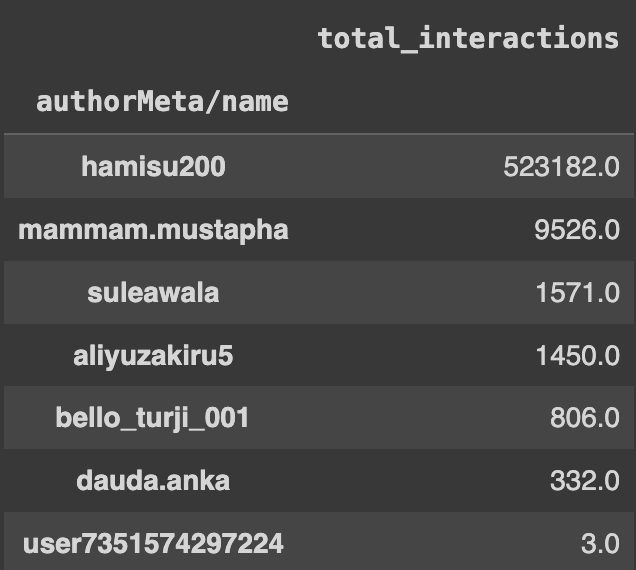

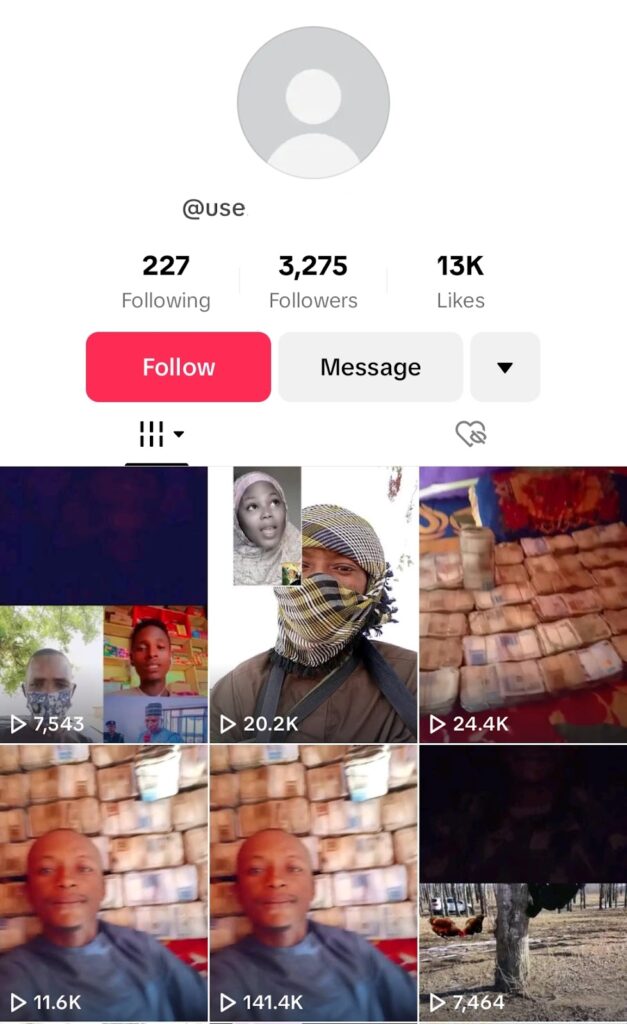

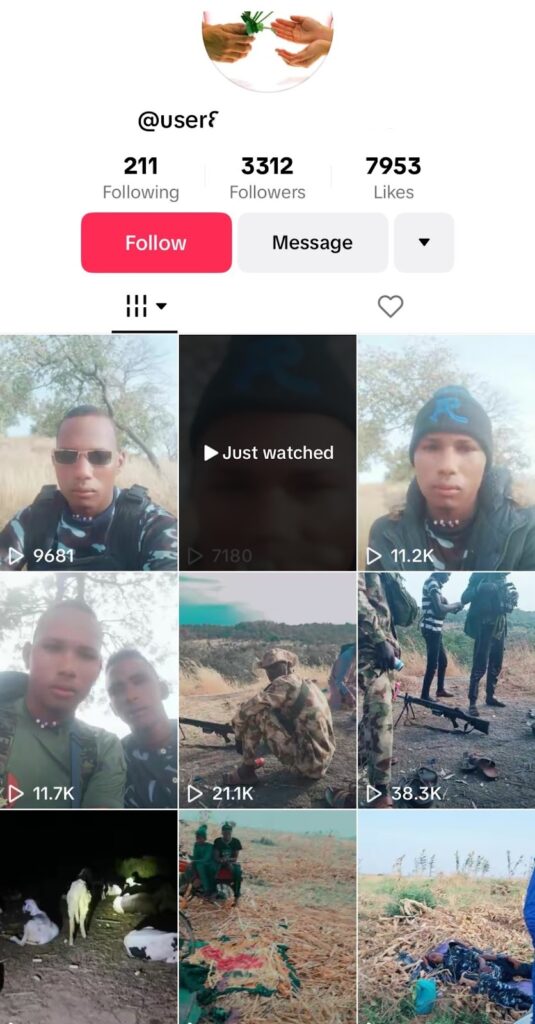

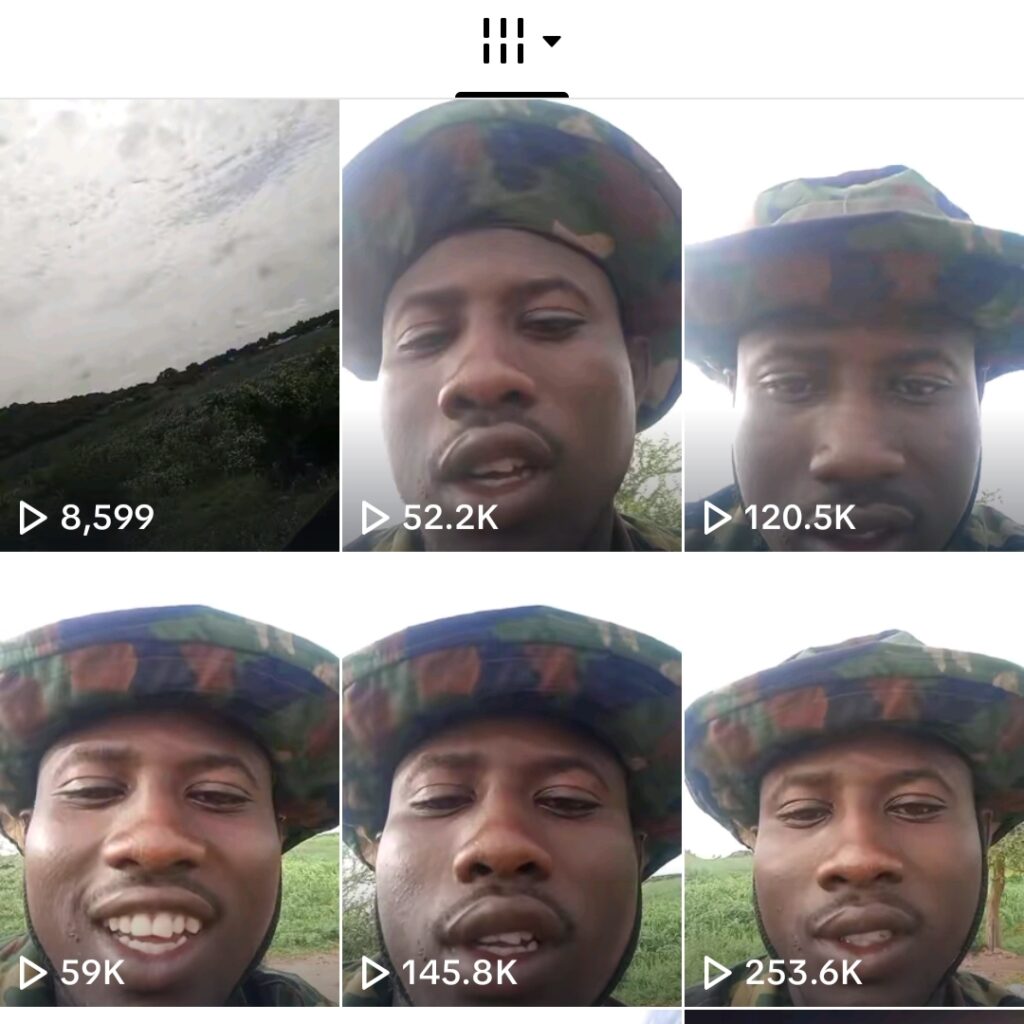

HumAngle monitored 25 accounts operated by these non-state actors and the reach of their posts over three months. Some accounts were banned during the research, while others remained active on the platform.

From the 25 accounts under our observation, we have collected 730 videos on TikTok. Our analysis of these accounts led us to the six most active accounts that have been spreading misinformation supporting the terrorist groups. The image below shows the total interactions they have received from the videos shared on their pages.

Violent rhetoric

Among the accounts monitored by HumAngle, one with the username @Musa.sauro (now taken down) emerged as a central node in the network of similar accounts. The account, which often features content glorifying acts of violence and promoting radical ideologies, is linked to several others that share similar themes.

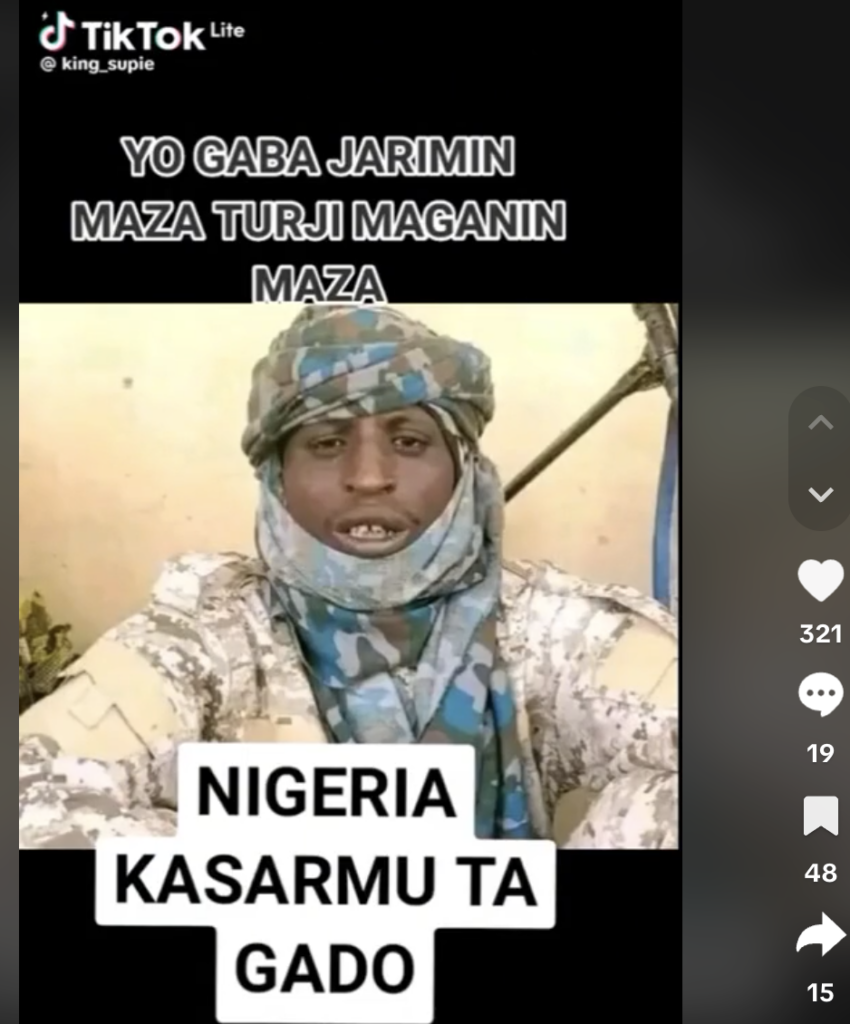

The videos frequently use militant imagery, such as uniforms and weapons, alongside rhetoric to undermine military campaigns in North West Nigeria.

In one of the videos uploaded, the account user threatened to continue attacks on people if the Zamfara Governor refused to reconcile with them.

“Dauda is the problem,” he said in Hausa, referring to the state governor, Dauda Lawal Dare, who ruled out any negotiation with the terrorists after the previous ones failed. “And since he is not listening to our demands, peace will not be seen.”

This is the same rhetoric that another account, @rabemagarya3, shared on his page. Rabe, who identifies with the Bello Turji gang, has over 36,000 followers and is one of the notorious terrorists on the platform. He constantly attacks the authorities in the videos and promises more physical attacks on civilians.

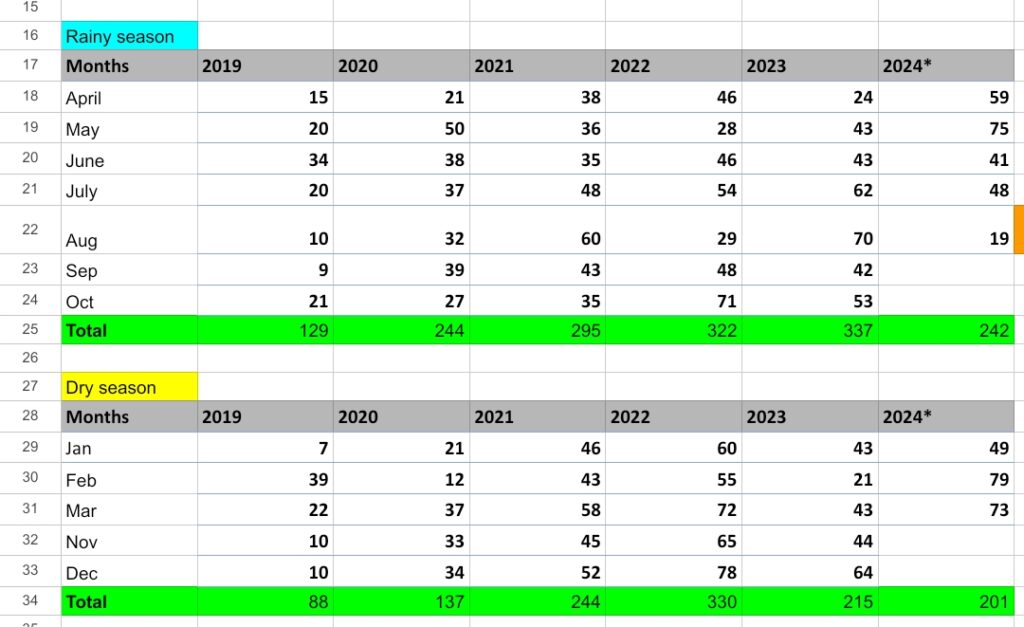

“Since your state governments aren’t ready to listen to us, wait till the rainy season when we will storm your villages,” he said in one of the videos. It is believed that more terror attacks take place during the rainy season as murky roads and other factors frustrate counter-terrorism measures in rural areas.

Data curated by HumAngle from the ACLED has shown a spike in attacks during the rainy season in Northwest Nigeria.

The accounts also strategically utilise trending sounds and hashtags to increase their reach, drawing in vulnerable or like-minded individuals who might be susceptible to swallowing the propaganda. The terrorists use Hausa and Fulfulde songs as a background for dances, including, ironically, the political songs praising Nigerian authorities.

This web of accounts fosters a virtual community where extremist views are normalised and encouraged. During the recent national protest in Nigeria, Rabe called on people to take arms and wage war.

“My advice to the protesters is to buy guns and wage war since everyone has been denied his rights,” he said in the video that was seen by over a hundred thousand people. “Wage riots, attack people, and we will collaborate with you.”

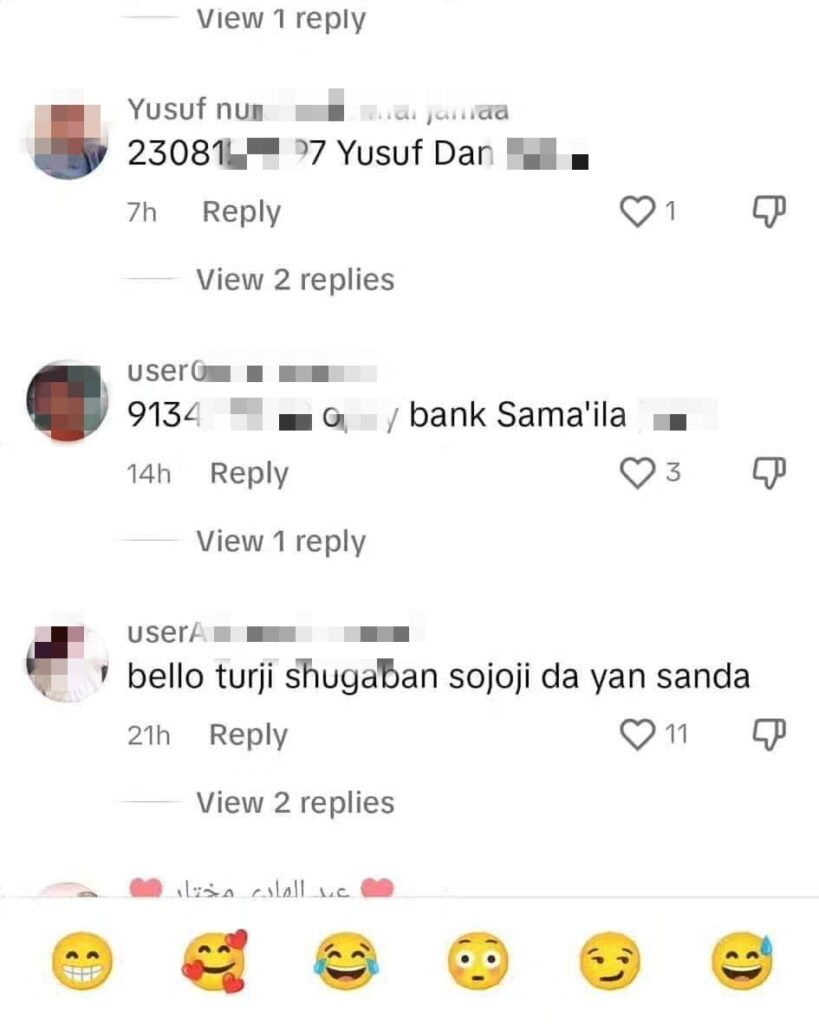

He even promised financial incentives to people following his account. In one of his viral videos, he called people to comment with their account details and promised to send them money. Hundreds of people obliged.

The network surrounding @musa.sauro and @rabemagarya3 comprises several related accounts, mostly with TikTok-generated usernames. These accounts often engage with each other by sharing, commenting, and liking their content.

List of some Tiktok accounts monitored by HumAngle:

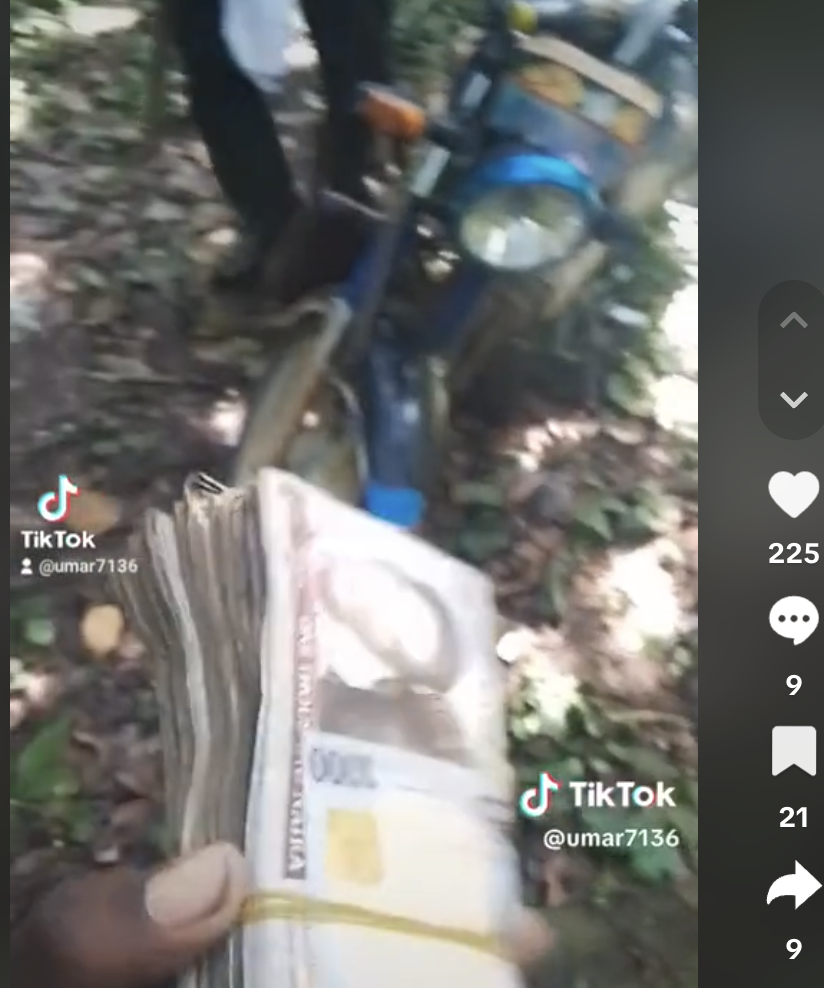

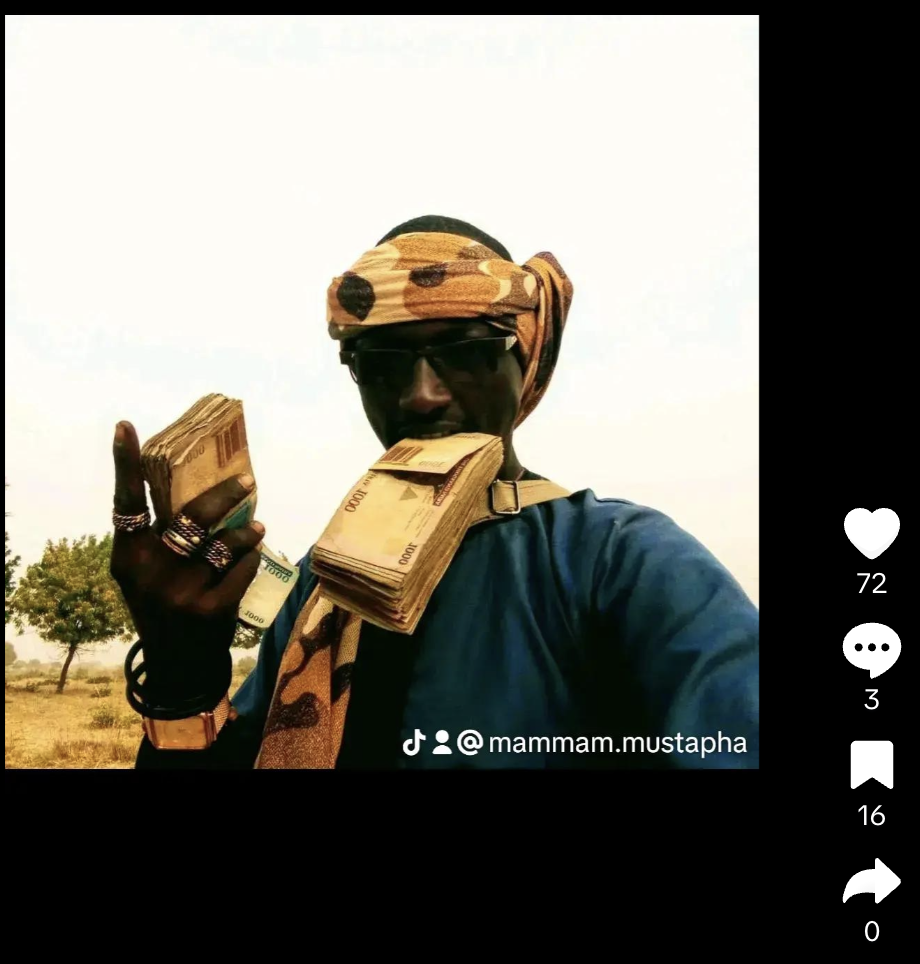

The accounts post statements from their terrorist leaders, show their daily lives, and flaunt ransom money collected from kidnapped victims. One post showed the traditional leader of Gobir, Sarkin Gobir after he was beaten to a pulp, begging for government intervention to save his life.

In another video, the terrorist kingpin Bello Turji was shown claiming that the State Minister of Defense, Bello Matawalle, sponsors his rival terrorists in carrying out their operations. He accused him of supplying weapons for a mass abduction done in a Kaduna public school.

Propaganda playbook

Videos produced by the terrorists on TikTok often feature heavily armed men in military uniforms, brandishing weapons and boasting of their exploits against Nigerian security forces or the ransoms extorted.

These clips are interspersed with anti-government rhetoric and ethnic colourations. Sometimes, they portray themselves as victims, not perpetrators, to justify their actions. Perhaps the most concerning is the clear focus on normalising and propagating their criminal activities.

The central message is clear: joining the bandits offers a path to power, respect, and financial gain. To bolster this appeal, the videos often include disinformation, exaggerating the bandits’ successes and downplaying their losses.

Responding to some of the videos, some TikTok users asked how to join the terrorists. “My friend, tell Bello Turji that I want to join your group,” one person commented in Hausa. Another account proclaimed, “Bello Turji is the president of Nigeria.”

Ethnic sentiments are also manipulated to heighten tensions and foster division. This helps them to position themselves as defenders of their ethnic group against external threats, particularly local vigilantes (Yan Sakai), who they accused of being Hausa militias. This tactic not only fuels recruitment due to ethnic feelings but also deepens existing grievances within divided communities.

The impact of this propaganda is profound. This online campaign has contributed to the erosion of trust in the government and security forces. The bandits’ portrayal of these entities as ineffective has resonated with many.

“The point is, you [Nigerian security persons]’re only good at arresting unarmed, peaceful and patriotic Nigerians who are only agitating for a country that will work for you and me. You’ve never been successful at arresting and prosecuting the real criminals,” one X user complained in reaction to the federal police spokesperson’s response to a post sharing terrorist propaganda from TikTok.

The spread of propaganda within communities has fueled polarisation, undermining social cohesion and exacerbating existing tensions. An account with the name Hausawa Tsantsa on Facebook claimed that from analysing over 30 of the TikTok accounts, he concluded that 99.9 per cent of the terrorists were Fulani.

“We Hausa people need to come out and defend our brethren that are being killed every day,” the account posted.

Challenges in content moderation

The TikTok guidelines on removing content that spreads terrorist propaganda or promotes violence are evident. “We do not allow gory, gruesome, disturbing, or extremely violent content,” it states. The platform uses an automated system to take down content that violates its community standards.

Although some accounts monitored by HumAngle have been taken down for violating TikTok policies, many others have remained untouched, indicating the limitations of the current artificial intelligence-powered model. The terrorists’ use of Hausa and sometimes Fulfulde, especially in videos showing no weapons, has made moderation more complicated. Although TikTok is available in 75 languages, neither Hausa nor Fulfulde is one of them.

This linguistic gap presents a significant challenge for the app’s content moderation efforts, allowing some propaganda videos to slip through the cracks. Experts argue that this oversight has created a loophole that terrorists in North West Nigeria are exploiting with increasing sophistication to bypass detection.

“The fact that TikTok does not support Hausa in its automated moderation system is a serious flaw,” said Silas Jonathan, a research and digital investigations manager at the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID) in Abuja. “These groups are aware of the limitations and have adjusted their strategies accordingly, migrating from platforms such as Facebook and moving to TikTok to create a community.”

We have also noticed that terrorists often use subtle language and avoid overt violence to evade detection. Indeed, many of the videos flagged by experts feature subtler forms of incitement-rhetorical speeches, trending songs, or coded language that glorifies terrorism without overtly violating the platform’s guidelines. By omitting visual cues like blood and physical violence, the videos often evade detection by the automated systems TikTok relies on to enforce its community standards.

While effective in many contexts, the platform’s reliance on AI for moderation is not foolproof. The AI struggles with nuanced content, particularly in less commonly spoken languages or dialects. According to Jonathan, TikTok has not yet shown any interest in expanding its language capabilities to include Hausa — a language spoken by over 50 million people across West Africa — creating a significant gap in its global content moderation strategy.

“The [terrorists] are clever in how they craft these messages,” said Abdullahi Abubakar, a journalist covering the activities of the terrorists in the region. “They are not just spreading fear; they are also trying to win hearts and minds, especially among young people.”

Abubakar explained that the engagements they get from followers and other users of the platform suggest they are gradually winning people over. “No right-thinking person gives his account details to terrorists,” he concluded.

Sometimes, videos circulate for weeks or months before they are flagged and removed, giving them ample time to go viral and reach a wide audience. The speed at which content can spread on TikTok, combined with the platform’s recommendation algorithm, means that even a single video can substantially impact before it is detected and taken down.

In response to mounting criticism, TikTok has increased its collaboration with local non-governmental organisations to better understand the cultural and linguistic nuances of the shared content. However, progress has been slow, and the platform has not reached the Hausa-speaking parts of Nigeria. Many in the region remain sceptical of the platform’s ability to police itself effectively.

“There’s a disconnect between the global reach of these platforms and their understanding of local contexts,” observed Jonathan. “Until TikTok addresses this, the bandits will continue to find ways to exploit the platform for their own ends.”

This article was produced through a collaboration between HumAngle and Code for Africa’s AAOSI programme. The AAOSI initiative is a collaborative effort to empower media and NGOs in African countries to combat disinformation and propaganda through training and resources, aiming to strengthen information integrity and foster collaboration among investigators in the region.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter