Maigu: The Niger State Community Where Terrorists Camp, Rape, Launch Deadly Attacks

The terrorists, who would later align with Boko Haram, use Maigu in the Shiroro area of North-central Nigeria as a route for launching attacks on other settlements, and as a rest point where they collect taxes and rape the community’s women.

Pastor Dogo, 45, is never returning to Maigu in the Shiroro Local Government Area (LGA) of Niger State, Northwest Nigeria, for certain reasons: one is the haunting fear he experienced as he hid on a hill when terrorists passed through; then there is the enforced tax on the community where they are made to pay a certain amount of money to be left alone. And the third, the memory of how girls and women were sexually assaulted, particularly the case of a married woman gang-raped by the same three people on two occasions.

A major route

Once, in 2016, Dogo was part of an evangelism team that visited Maigu. Then, terrorists, once referred to as cattle rustlers and later bandits, made off with one man’s cattle. When the owner confronted them, they killed him.

Little did he know fate would demand he relocates to the area as its people’s local pastor three years later. At that time, cattle rustling appeared to be the sole mission of the terrorists, but in 2020 things became worse.

“We began to hear news of killings in other places,” Dogo says. “They only used to pass our village in 2020.”

The terrorists used to make it clear that they would only attack a place where their own people were harmed.

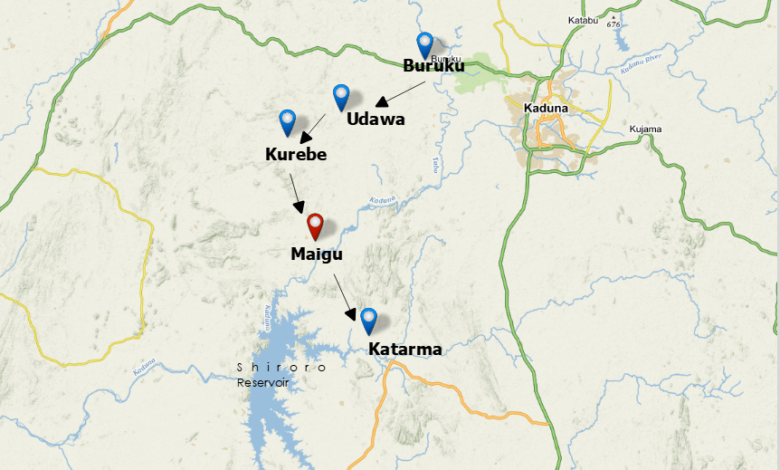

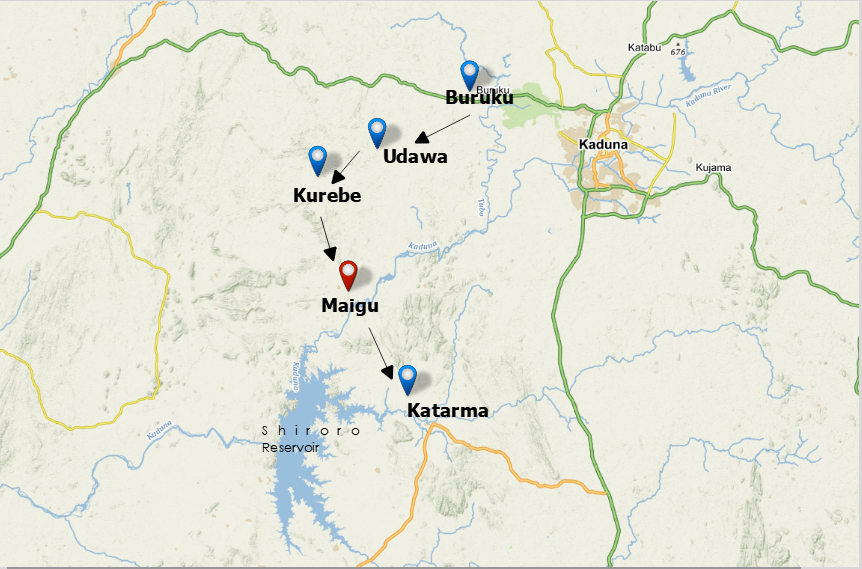

“There were three pastors in the area. We used to gather monthly to pray. It was a tricky situation in Maigu. Anytime the terrorists wanted to attack Katarma [in Chikun LGA of Kaduna State], they follow through Maigu. It served as a route to Minna [Niger State capital] and several other parts of the state.”

Once, in 2021, the terrorists approached Dogo in front of his house. They were returning with rustled herds of cattle and asked for blankets. He obliged them.

“They liked to get things like these when they were passing through. When you have it, they collect it,” he explains. “They were two on a motorcycle. Others also went to other houses.”

By morning, as they prepared to move out of Maigu, the terrorists returned Dogo’s blanket to him. “Sometimes, when their leader isn’t the kind type, he won’t tell his boys to return the blankets. But a kind one will move around the village and announce that if they had collected blankets from any house and have not returned them, he should be told. When we say they have been returned, they pass.”

By 2022, if they intend to attack a place, they keep their motorcycles in Maigu and trek. Dogo remembers a time when the terrorists went to set off a bomb. “We heard that they were seen around Galadima-Kogo,” he points out. “When they hear that soldiers are coming, they go and put bomb.”

In Feb. 2020, explosives believed to have been planted by terrorists were reportedly detonated at Galadima-Kogo, also in Shiroro. Many people were killed in the explosion including four officers of the Nigeria Security and Civil Defence Corps (NSCDC).

“How we knew they were the ones [responsible for the blast] was that they had kept motorcycles in our area,” Dogo insists.

Boko Haram and their allies

Unlike other terrorists groups, Boko Haram is an insurgent group bent on establishing an Islamic caliphate, beginning from the Northeast. But there are indications that they are now aligning with other terrorists mainly known for kidnapping for ransom.

Once, a vigilante group hid at Kusasu market, a community within Shiroro. “Then we saw Fulani pass by on motorcycles. We were afraid and didn’t know where to run to. Around 4 p.m., we heard the shooting. There was a clash,” Dogo narrates.

“There’s a hill we usually climb that, if they are passing through, we see them, and when they enter our houses, we will also see them. Sometimes we even sleep there, particularly when they are still around and we can’t enter our houses. That was how we saw them return with their wounded.”

Later, the vigilante group burnt down Kusasu market, a move Dogo insists helped rid the community of Boko Haram to some extent.

“What happened was, there was a time when Boko Haram attacked homes and vigilantes fought back. But the terrorists thought it was the townspeople who were fighting back and didn’t know they were vigilantes. They didn’t know that people had already run off.

“At that time Boko Haram [also known as Jama’at Ahl as-Sunnah lid-Daw’ah wal-Jihad or JAS] and some of the Fulani had formed an alliance,” he continues. Gradually, community members learned to differentiate between the two by the types of head covering or caps they wore. They noted that Boko Haram wore a turban while the other group of terrorists donned a type of cap, usually long, that reached the back of their necks. Also, Boko Haram in the area usually speak Hausa while the others use a different language.

A HumAngle report suggested the presence of Boko Haram in Dogo’s local government area in 2021. “The initial picture of the attacks in Munya and Shiroro LGAs painted by residents, vigilante forces, and security officials is a complex one that suggests that jihadists–likely JAS–are indeed operating in Shiroro, but that insecurity in the wider state has been driven more by the type of ostensibly non-ideological “banditry” that has rocked Nigeria in recent years,” it said.

It was at this point of understanding the dangers confronting them that many started packing their belongings. For a whole week, using a motorcycle, Dogo shuttled between Maigu and Shiroro Dam, where he later got a vehicle that transported his property to Gwada, located approximately 33 km away from Minna.

“Some of my things are still there today,” he says.

Terrorists from Buruku

Unlike other settlements within Niger State, the terrorists using Maigu as their path to other communities and resting place seemed bent on keeping a relatively non-violent relationship with Maigu residents.

Compared with the reputation terrorists have in other parts of the northern region, Dogo says “they never really bothered us a lot because it is said they come from as far as Buruku after Mando.”

Located in Kaduna State, Northwest Nigeria, Buruku is about 25 km away from the state capital and approximately 175 km from Abuja, Nigeria’s Federal Capital Territory (FCT) in the North-central region.

In March 2022, the Kaduna State Police Command said they foiled a kidnapping attempt at Kwanan Janruwa, along Buruku-Birnin Gwari road. Terrorists had reportedly blocked some commuters along the route. This is one of several incidents.

Way back in Dec. 2021, 70 travellers were reportedly abducted around Udawa village after Buruku in the Chikun area of the state.

“Those who know the place say Buruku is very close to their [terrorist] camp. There’s a huge forest there. People who live around there know that Boko Haram are there. Our problem is the route through our village. If they want to go to Katarma or Minna, they follow through Maigu,” Dogo explains.

How they survived

Communication synergy is one reason why residents of Maigu survived the terrorists’ onslaught. When locals spot terrorists crossing the road around a place called Wudawa, they make frantic phone calls to neighbouring communities whose residents then flee their homes and hide in the forest.

“Because there’s a hill where we hide, whenever they are gone we get information that they have crossed a particular river, then we return to our homes. When they are returning again, those in Katarma call our phones and tell us exactly where they are,” Dogo explains.

Katarma, a settlement of about 15 LGA, has suffered years of attacks by terrorists who kill and kidnap for ransom. Many residents, including Dogo’s colleagues, abandoned their homes and moved to places like Sarkin Pawa in the Munya area of Niger State.

“As I speak to you, people in Maigu have told me that they have returned to their homes. But I told them I can’t return, because if I do, my life will be in danger.”

The terrorists always knew when one is a new face after a prolonged period of time. Dogo was certain that since he had not been there for a while, they would grow suspicious. “When they see you, they will inquire and accuse you of being a secret agent that will help the authorities get to them. They know everyone because they relate with the people and request things like food.”

Once, they met Dogo in front of his house and asked him to repair their motorcycle. He replied that he was not a mechanic. Apart from meeting people in their homes, the armed group also had a habit of hanging around the marketplace.

“If not for the vigilante, we wouldn’t have survived that place. If they hadn’t burned down that market, Boko Haram would have taken over because they were dominating the market. They ride their motorcycles through the market with their firearms in a domineering manner.”

One major reason the gangs preferred the Maigu route is the relatively better road, Dogo points out. “It leads to Kurebe [also in Shiroro LGA] which is on the road to Wudawa. Now that’s where they go.”

Back from their adventures, the terrorists formed a habit of selling stolen goods, such as phones, in Maigu. Dogo warned his congregation never to patronise them.

Raping spree

There was the other side of what happened in Maigu that Dogo finally revealed. Rape was one crime the terrorists committed openly. Once, three men came to a house and forced a man’s wife to go with them. They later let her go. But this was not all. They returned days after for the same woman, and this time released her the next morning.

“When she returned, she could hardly walk,” Dogo says, adding that he advised the husband to relocate his family or the terrorist won’t stop assaulting his wife.

At another time, a woman and a girl were taken away and sexually assaulted. Yet, some locals are still reluctant to leave their homes and farms behind.

“I told them that the terrorists have a plan for taking it easy on them. They know that once the people are able to farm, they will be reluctant to abandon their homes later on. So, they don’t kill, but come and say if the whole community doesn’t give them money, they will kidnap. When they are given, they return after six months.”

Currently, those who care to farm in Maigu must pay an enforced tax. This is not new. The terrorists there hardly bother to whisk people away to the forest like they do in other parts of the north.

In the past they had demanded as much as ₦200,000 from the community. With the demand met, they waited till harvest time and returned, insisting that there wouldn’t be harvest until they were paid.

Recently, in a statement by Emmanuel Umar, Niger state’s Commissioner for Local Government/Chieftaincy Affairs and Internal Security, the government commended the ongoing “intensified military operations in neighbouring states and in some local government areas as they neutralise terrorists and bandit activities.” He pointed out that many terrorists have already been eliminated in the affected LGAs of Shiroro and Munya.

The commissioner did not pick his calls or respond to text messages when HumAngle reached out, while the state’s Police Public Relations Officer (PPRO), Wasiu Abiodun, declined any comment on the subject.

But life as it were does not appear to have changed for the better in Maigu, especially now that it is the rainy season again. “I have advised the people to leave and rent farmlands elsewhere, but they are attached to their own farms which they consider to be free land,” Dogo says anxiously.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter