Kaduna Shia Protest Killings: Families Mourn Death Of Six Young Men

In March, six young men, members of the Shia Islamic Movement in Nigeria (IMN), were killed while protesting on the streets of Kaduna, northwestern Nigeria. HumAngle spoke to the victims’ families.

Hajara Shittu had a premonition that day that her son would not return home alive.

This chilling feeling settled in her heart the moment she heard something was amiss in her city.

Earlier on March 16, 70-year-old Hajara had bid her son, Lawal Haliru, goodbye.

Word that there had been violence involving Shias and security forces began to filter into her neighbourhood, Unguwan Sanusi, in Kaduna South Local Government Area (LGA), northwestern Nigeria.

Around 6 pm, Hajara heard some children talking loudly about violence in the Bakin Ruwa area of Rigasa.

They said members of an Islamic sect known as the Islamic Movement in Nigeria (IMN) had been shot.

Hajara’s unease intensified.

The conflict

The presence of a group of followers of Shia Islam in Kaduna has been the flashpoint of conflict several times in the recent past.

Shiism is a minority faith in Nigeria and has historically faced discrimination from Muslims in other sects.

The differences in religious doctrine have driven conflicts elsewhere in the world. The Shias in Nigeria are not popular with the government or with purist Sunni elements of the religious establishment who view them as idolators and heretics.

The last time Shia and security agents clashed in Kaduna was in Aug. 2022.

The IMN said at least six of its members were killed and 40 followers of its leader Sheikh Ibraheem El-Zakzaky, were injured during the group’s Ashura mourning procession in Zaria. Ashura is a Shia celebration that marks the anniversary of the killing of the Prophet Muhammad’s grandson Hussein.

In Sept. 2021, at least two people were killed in Abuja, Nigeria’s capital, when security forces allegedly shot IMN members who were marking a religious event previously banned by the Nigerian government. Authorities, however, said the crowd were “unruly and riotous” and denied that there had been any casualties in the encounter.

In Dec. 2015, the army attacked the IMN sect in Zaria, Kaduna State. Hundreds of people were killed, and the house of the founder, El-Zakzaky was burned down. El-Zakzaky was arrested and detained. In the more than five years before his acquittal, there were several demonstrations by the sect and clashes with government forces.

Since then, the IMN had vowed to continue protesting until the passports of their leader and his wife were released to enable them to seek medical attention abroad.

Relatives and witnesses say security forces that had been escorting a government convoy passed through the area and opened fire on the crowd.

The Kaduna state government has not commented on the incident. Spokespeople for the governor were contacted, but did not respond to HumAngle’s queries.

Kaduna police say the protestors were the aggressors and the police acted “professionally”.

“Security operatives attached to the convoy of the Kaduna State Governor have cleared the Bakin Ruwa axis of Rigasa, Nnamdi Azikiwe Expressway after armed hoodlums suspected to be members of the proscribed Islamic Movement of Nigeria (IMN) who attacked law-abiding citizens and had prevented motorists from plying the route,” the Kaduna State Command said in a statement signed by DSP Muhammad Jalige, a day after the killings.

The statement also said, “the hoodlums, on sighting the convoy, began firing weapons/stones, hitting several private vehicles along with a few in the convoy.

“The security operatives professionally contained the miscreants without the use of force. Some of the hoodlums strongly suspected to be members of the Islamic Movement of Nigeria (IMN) were arrested. Investigation is in progress.”

But survivors of the incident describe a moment of chaos, where the demonstrators were gunned down by police from the backs of pickup trucks, almost indiscriminately.

A mother’s premonition

People kept trooping into Hajara’s home, asking after her 23-year-old son, Lawal.

“He’s not coming back,” she repeatedly told them.

Some challenged her for being negative and she explained that her son was not the type to stay late. And worse, it was said that some Shia members were killed. Hajara was adamant – Lawal was dead.

“I felt it in my body,” Hajara told HumAngle, “my son was never coming back home.”

When neighbours rebuked Hajara, she said: “He is dead. Keep your eyes open.”

Hajara told HumAngle that as night fell, she looked at the people around her and said, “You see?” her son was not one who was normally so late coming home.

In the morning, Lawal’s brother came into the house. He looked solemn.

Hajara took one look at him and said her words were confirmed.

“He then came to me and said I should come and see how Lawal was. I told him sternly not to hide the truth from me. He insisted that Lawal was alive, and I said no, he wasn’t, I just needed to go and see his corpse.”

That was how Hajara was taken to a house on a motorcycle. Right outside, one of Lawal’s brothers held her. He was crying, and so she began to weep.

“When I saw him, I shouted Allahu akbar! Allahu akbar! Lawal, Is this you like this? Muhammadu Lawal, are you the one here? May God forgive you. May God give you rest. Death is rest, but may those who did this reap what they have sown.” Hajara kept repeating this until she was dragged out of the room.

Her lamentations continued, she said: “So this is the last time I will see you, Lawal? This is the end of our play and laughter together?”

After giving this account, she was quiet for a little while and talked about Lawal’s work as a tailor. He was also in his second year in senior secondary school.

A widow, Hajara concluded: “I had seven children. There were formally eight, but one died. Now, with Lawal gone, they are six.”

Lawal was not the only one to die that day. About 1.3 km away in Badiko, a neighbourhood in Kaduna South LGA, another family mourned another death.

A son’s parting gift

Days before Ibrahim Abdullahi’s death, he paid his mother, Maimuna Abubakar, and his siblings a visit. It was close to Ramadan, the Islamic fasting period and Ibrahim was concerned that the house lacked food.

He promised to remedy the situation and also buy new outfits for the upcoming Sallah celebration.

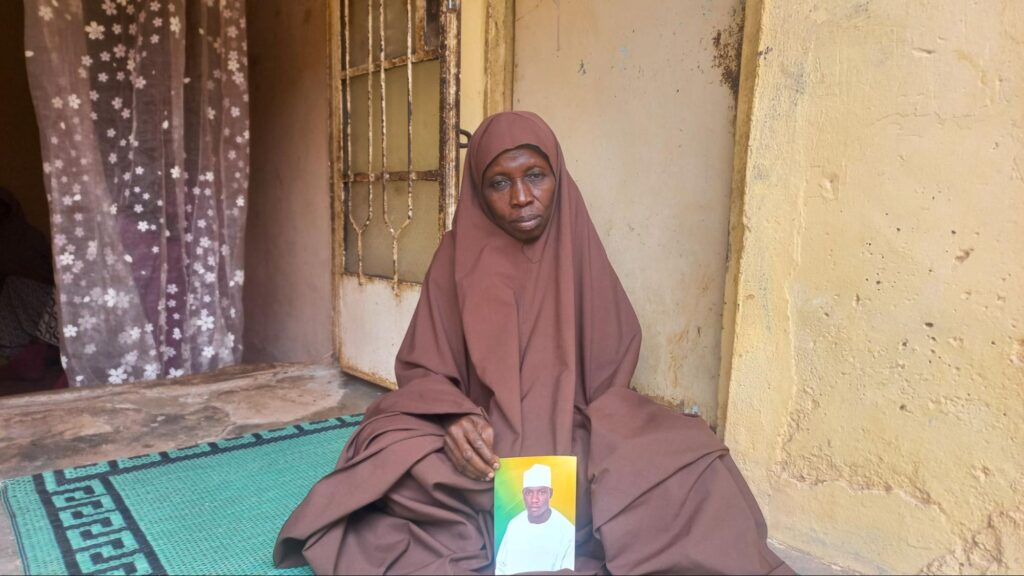

Ibrahim, 35, fulfilled his promise, Maimuna told HumAngle from her place on a mat in her living room.

In her seventies, her voice shook as she talked about her late son. Yet there was something else around the edges of those words – pride.

The day Ibrahim was shot dead, their clothes for Sallah had already been paid for. As they mourned him that day, the package was delivered. Nobody had been left out of this parting gift. His wife had hers, his children too, and siblings. Then Maimuna herself.

“The clothes were many,” Maimuna said, her voice tinged with astonishment, even weeks later.

During the festive season, they would wear these clothes with pride and maybe with some sadness deep in their hearts. But they would remember Ibrahim with a smile on their faces, she said.

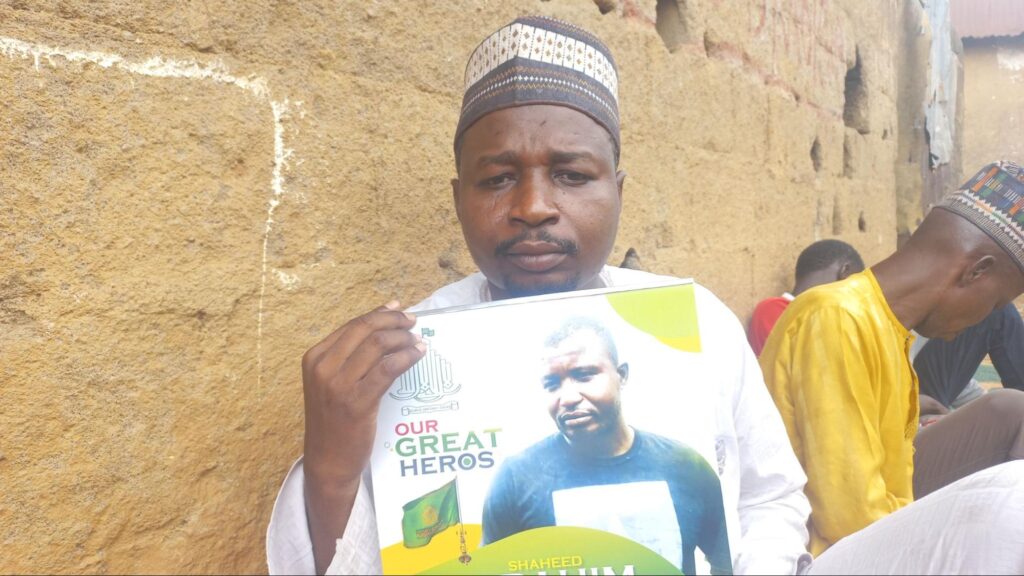

Outside the compound, two obituary posters were pasted on a wall – one of Ibrahim and the other of a family friend, Abdulmalik. Men sat on mats in mourning. Among them was 40-year-old Muhammadu Auwal, Ibrahim’s elder brother.

Like their mother, Muhammadu talked about his brother with pride.

Ibrahim was the fourth in a family of seven. He made a living dealing in motor spare parts.

“I was in the market when I was called and told that security forces accosted them while they were protesting,” Muhammadu began.

“I was seriously affected by the news because Ibrahim was a pacesetter here, especially among the youths. When his corpse was brought, people filled the neighbourhood. We were shocked.”

Muhammadu described Ibrahim as “a mentor” who wanted to train the most stubborn youth. He was known to give encouragement even to those with addictions to go and acquire a skill. People from many communities would mourn him, his friend said.

“He doesn’t allow anyone to get cheated.”

During the protest, Ibrahim had called his elder brother on the phone to say he and other Shia members were at the demonstration. The security forces were shooting, and he saw the governor, he said.

“Later, I heard that he had been shot. I returned home to meet people crying.”

Their family friend, Abdulmalik, had been at home resting while the crisis raged. When he heard that Ibrahim was shot, he dashed out to his friend’s house.

The crowd building presented a problem. Muhammadu told HumAngle that, although upset by the sight of Ibrahim’s corpse, he and his friend did not want there to be more violence. Muhammedu said he did not want the youths in Badiko to rise in anger.

Word spread that security agents were approaching the area.

The two friends tried to control the crowd, Muhammadu said. That was when Abdulmalik was shot.

“My son was the calm type and always peaceful,” Abdulmalik’s mother, Hafsatu Ahmad, said in their bungalow located a short distance away from Muhammadu’s home.

Aged 60, Hafsatu had a hint of a smile as she spoke about Abdulmalik.

“On that day, I had gone out and returned to find him at home. He was lying down, and I asked him, ‘didn’t you go out?’ and he said he had a headache,” she said.

So mother and son chatted. Hafsatu informed him that she saw “your people” trooping out and then asked what was happening. Abdulmalik responded that he had no idea.

“We were still together when there was a call for prayers. So we both carried our ablution jugs and went to pray.”

When a while later, Abdulmalik heard about Ibrahim’s death, he instantly left the house.

Hafsatu did not know it would be the last time she would see her son alive.

Engineering dream cut short

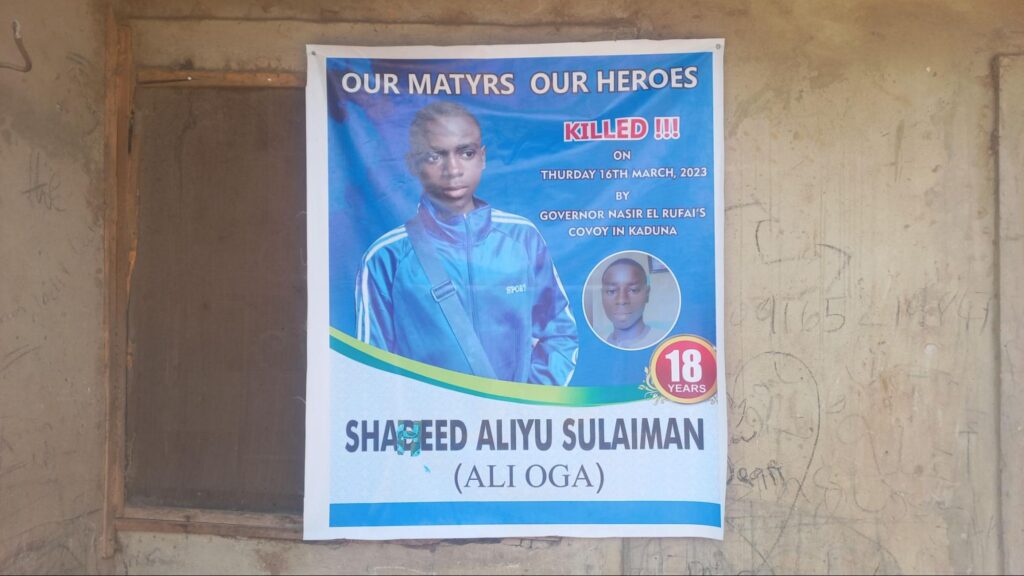

Aliyu Suleiman died three months after his dream of studying mechanical engineering came true.

Before his death, the 18-year-old was constructing burglary-proof fences and doors at a spare parts market in Kaduna. He was a handy teenager who assisted in his father’s welding shop.

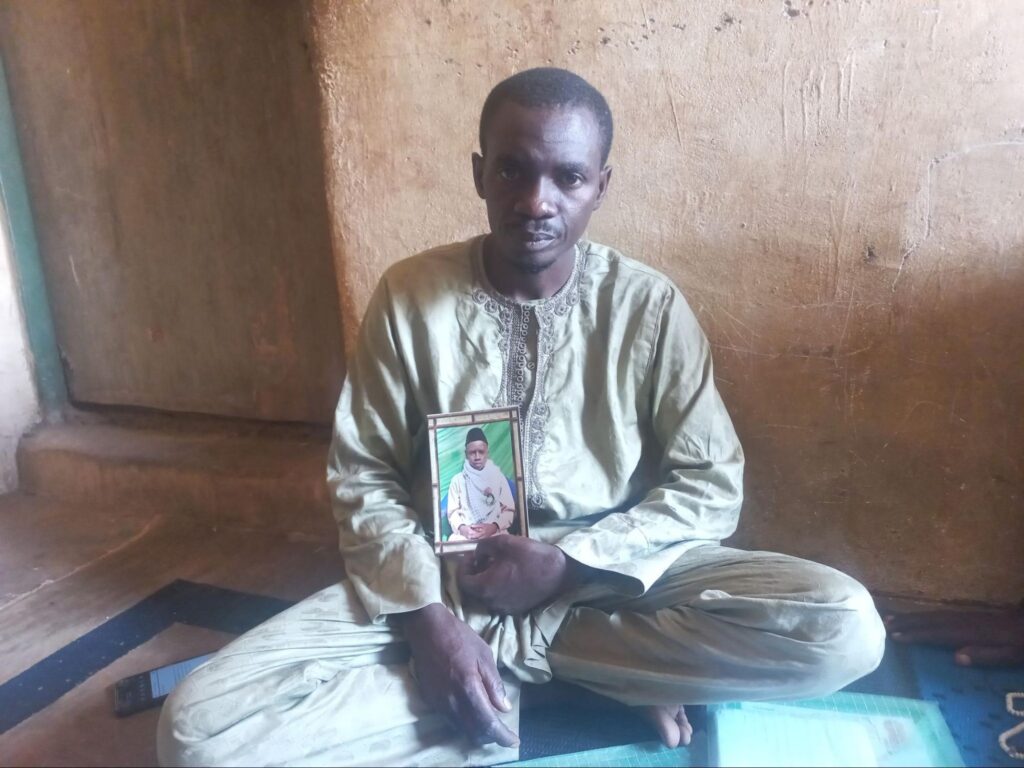

“When he is not at school, he is at the workshop,” his father, Suleiman Abdullahi, told HumAngle.

The 43-year-old was seated on a mat in his living room in Rigasa. Around him, several men came to pay their condolences.

Aliyu was the third child among 15 siblings, the youngest being three and the eldest 23, he explained.

He had learned Yoruba and was teaching others, and had made great strides in his Islamic education, his father said. He had finished school and was about to go to Kaduna Polytechnic to study engineering.

“I was at my shop at the spare parts market when I got a call that Aliyu had been shot. The last time I spoke to him was on the phone. I wanted to know the cost of the food we usually ordered for lunch.”

Aliyu’s elder brother, Muhammad Suleiman, was not far from the scene where his sibling died.

Aliyu always looked up to 24-year-old Muhammad. His older brother had already finished a diploma at Kaduna Polytechnic.

They were so close that on the day of the protest, Muhammad constantly made a point of knowing where Aliyu was, whether at the front or at the back of the group.

“Aliyu was among those chanting slogans while I and others controlled the procession,” he began. “We were protesting the government’s refusal to give our leader, El-Zakzaky, his passport so he and his wife could travel for treatment abroad.

The protest began on the road that led to Government House. A government convoy had already passed before they got started, Muhammad said.

“Later, I saw my brother go to the back of the procession, and I wondered what was happening there,” he said.

Then Muhammed saw the government convoy returning down the road with the mobile police escort. The convoy stopped and the demonstrators and convoy faced off against each other briefly, he says.

“I suddenly heard shooting. Someone by my side was shot. The mobile policeman that shot him then threw tear gas.”

Muhammad saw another friend, Yasr, shot too.

The shot that killed Aliyu went into the armpit, and the bullet came out through the side of his chest.

Bilkisu Adam, Aliyu’s 55-year-old mother, said despite the terrible wound “he looked like he would rise if you called him”.

She described her deceased son as different from the others. He was obedient and not troublesome.

“We are thankful to God that he made this the way he should go. God would not allow something to happen that we can’t carry. I pray he rests in peace,” she said and narrated her last moments with her son.

Bilkisu had gone to Unguwan Mu’azu, a neighbourhood not too far away, and returned to the news of what was happening at Bakin Ruwa.

She called Aliyu’s phone but could not reach him. Then she called his siblings and got the same result. That was when she decided to visit her neighbours and got the shocking news that her son had been killed.

“What gives me joy and makes me cry at the same time is that since I was with him, he never refused or rebelled when I asked him to do something for me. Even when he was sick. This is what makes me cry,” she said, sobbing.

“My backbone has been broken. I don’t know what they did to the government. I leave justice in God’s hands.”

A son’s goodbye

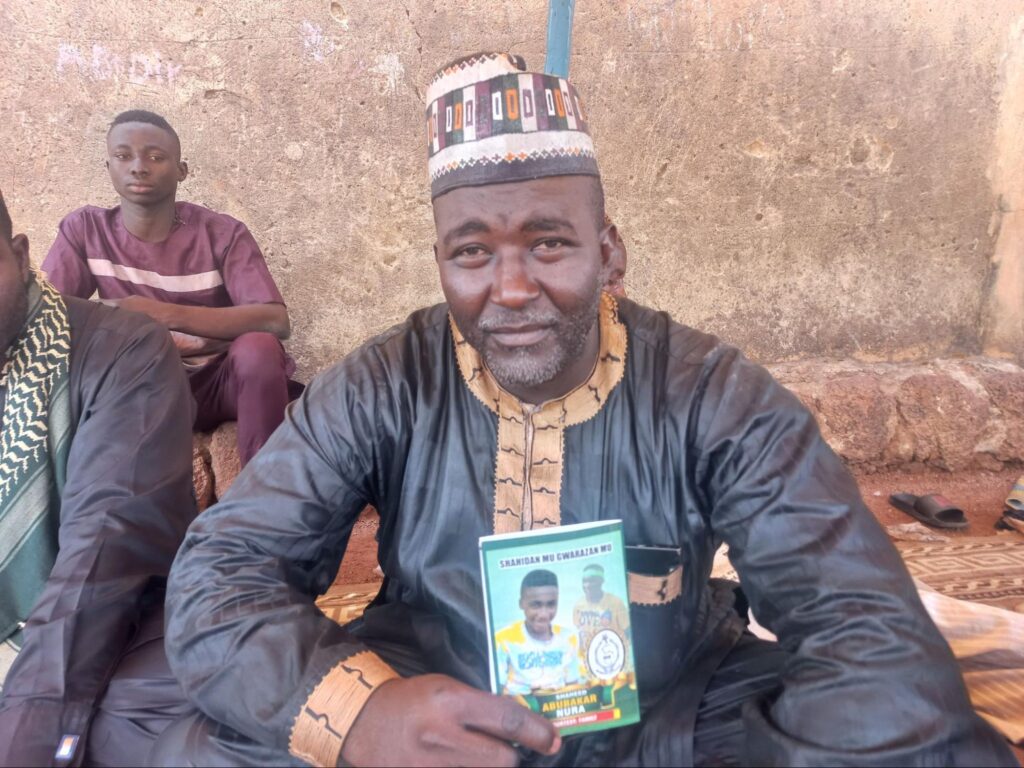

Nura Abubakar, 56, is a businessman who says his life depends on people he can trust. One of these people was his 19-year-old son, Abba, whom he entrusted with responsibilities, including custody of his credit card.

The second out of 18 children, Abba was about to round off his secondary school education when he was shot dead. He was also close to attaining a milestone in his Quranic education.

“He wanted to study nursing,” he said in front of his home, where he sat with visitors under a tarpaulin.

Then, in what sounded like a poem recitation, he continued: “He was my favourite child. Beyond that, he was my friend. But beyond that, he was my child…he was also more than a child.”

The day Abba died, he had returned his father’s credit card as though he sensed he might not come back.

“I refused and wanted to know why he was giving it back to me. But he insisted. That was our last discussion.”

Some customers had called Abubakar with the intention of buying a house. En route to the meeting, he heard about the violent conflict in Rigasa.

“I instantly felt a certain weight in my heart and called Abba’s phone, but he didn’t pick up. I left my car there and used a motorcycle. I went to where the incident was happening, around the bridge to Abuja road by Makarfi road,” he narrated.

“Then someone came to me and said Abba had been shot.”

Inside their home, Abba’s mother, 41-year-old Hauwa Shuaibu, recalled her last moments with her son.

“The day he died, he drove me home on his motorcycle, and I worried about him. He told me to just pray. As I crossed the street, something told me to turn, and there he was, waving at me. That is the last image I have of him.”

The injured mechanic who died afterwards

Yasr Samaila, 24, wounded in the clash, died a day after he was shot.

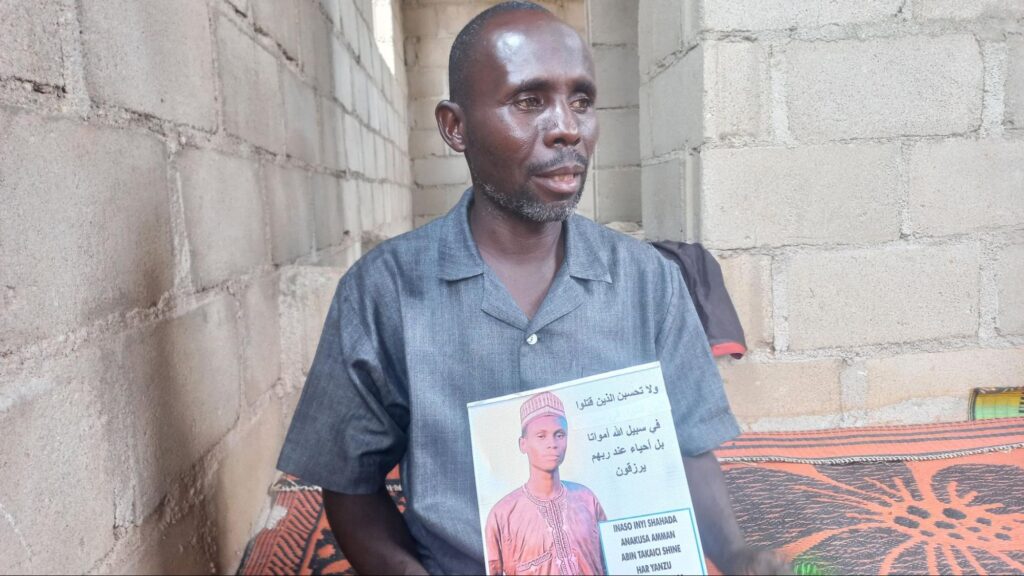

On the day of the protest, his father, Samaila Abubakar, 55, was busy in his shop where he sells cement.

He got a summons from his elder brother in Rigasa. Up till that moment, he knew nothing about the crises involving Shia members within the area he was going to.

So, when Samaila heard that his son had been shot, all he wanted was to see his boy’s condition with his own eyes.

“We now started trying to see how we could see them, but it was not possible. That night we could not sleep. His mother was not around, only his grandmother. In the morning, we went to Rigasa. That was when we learned that he died at dawn. I was grieved so much that I could not weep. I kept praying,” he told HumAngle at his home in Dan Mani, Igabi LGA.

Yasr had so much promise, his father said. He had benefited from both Islamic and conventional education. Plus, he had rounded off secondary school and was a skilled motor mechanic.

“Anytime I think about his life, it gladdens my heart. Since he was young, whenever he was going to the mechanic workshop, when I gave him and his siblings some money, he would spend his money on his siblings and everyone else until it was finished. This was money for his feeding. I will never forget this,” Samaila recalled.

He recalled a time when it rained for a long time, and everyone was worried about Yasr’s whereabouts.

“He didn’t return home until around 10 pm,” Samaila said. But their worry and inquiries as parents dissolved when they listened to their son’s explanation.

Apparently, Yasr had found a stranded boy who was wounded and took him home safe and sound.

As the annual fast of Ramadan approached this year, Yasr had wanted to know what he should do to make it special.

“He asked me what he should contribute, and I insisted that he decide for himself,” Samaila said as he concluded. In the end, Yasr drove his mother to a market in Rigasa, where they bought food. He also bought clothes for his mother and younger ones.

Outside their home, a few young men were packed into a Mercedes Benz with its bonnet open.

Yasr would have been one of them, his father said. His place would most likely have been under the bonnet, where he would be taking the lead in fixing the broken car.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter