IDPs Resettled To Marte Are Fleeing, Complain Of Hunger And Insecurity

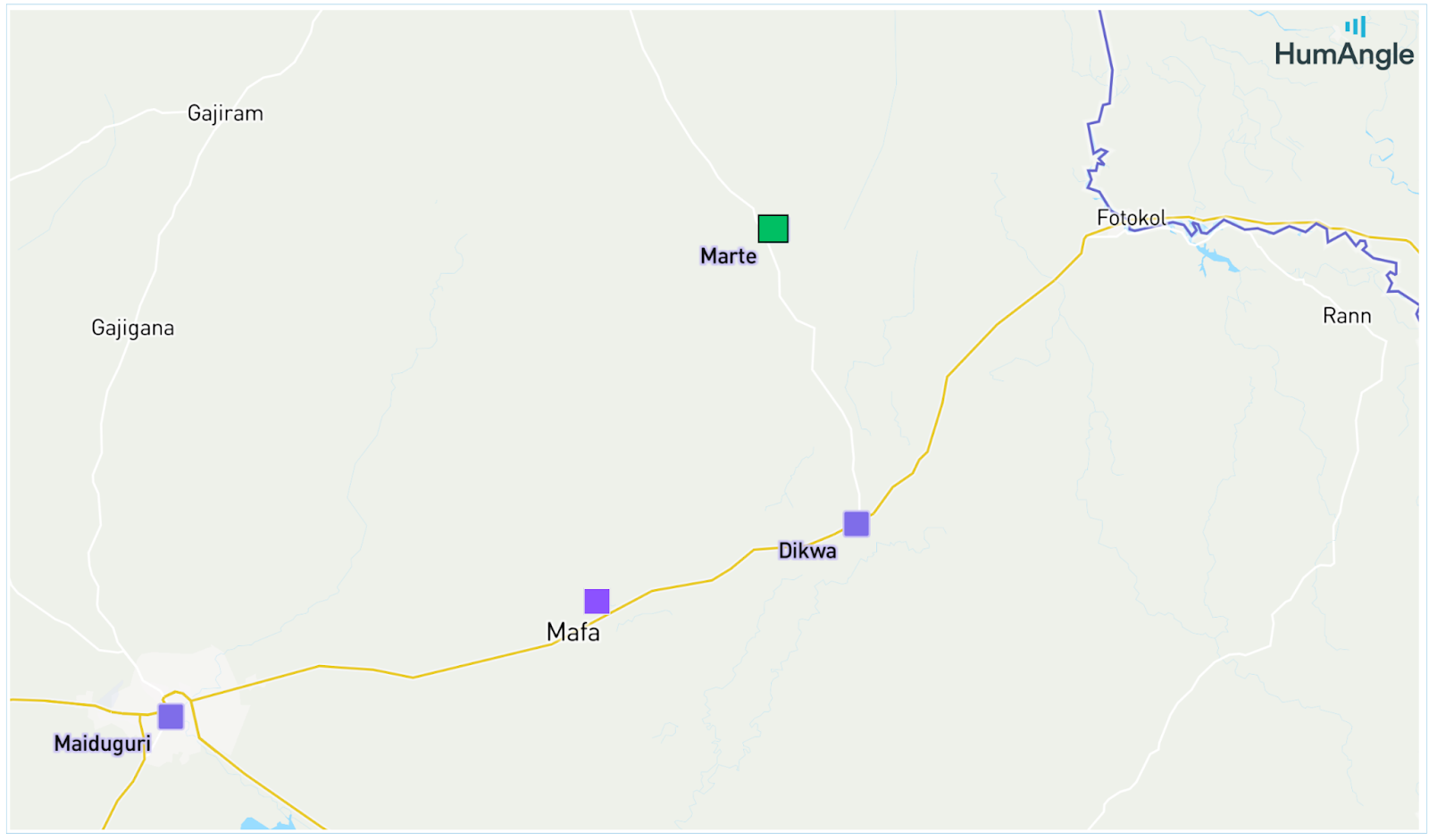

In November 2021, the Borno state government relocated thousands of displaced people from Maiduguri to Marte, the local government area they were originally from. But many of the returnees are now leaving in frustration.

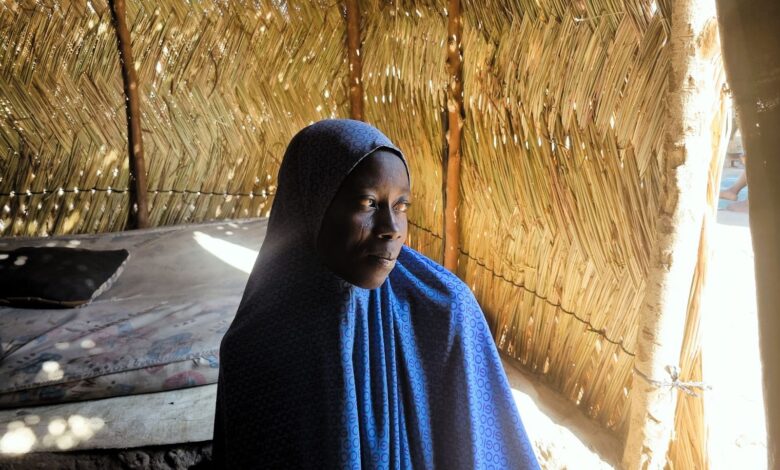

“The government told us they were taking us back to our homes. They also said we were not going to suffer when we returned. But here we are, suffering—”

Aisha Mohammed had left New Marte, her hometown in northeastern Nigeria, in 2014 as heat from the Boko Haram insurgency spread beyond Borno state’s nerve centre and planted danger in her very backyard over 100 kilometres away. She and her children found their way to the Bakassi displacement camp in the capital city of Maiduguri. Life was not the same, but they got by, especially with support from humanitarian organisations.

In November 2021, the state government shut down Bakassi Camp, swearing that most of the internally displaced people had shown a willingness to return to their ancestral communities — in line with international humanitarian law. It is not clear when it conducted this survey. Just like Aisha, many IDPs say they were assured they would be taken care of after their resettlement. The plan was for them to have access to farmlands, return to their original livelihoods, and become self-sufficient. Not all the IDPs at the camp bought this idea, fearing that their villages were still too unsafe for business as usual. But some trusted the government, packed their belongings, and climbed into trucks that zoomed off in a familiar direction.

Years later, many of the IDPs in those trucks are itching to escape again. Some have managed to undo their resettlement, pushed away from home by roughly the same factors that displaced them a decade ago.

Aisha gathered enough money and left for Dikwa last December when the hunger became unbearable. According to her, the resettled IDPs in Marte suffer through almost everything. Their major livelihood is rooted in fetching and selling firewood. They return with bundles in the afternoon and then sell to those who convert them into charcoal, but demand for the fuelwood is not as high as it was in Maiduguri. This not only means that getting a buyer is tougher but also that the item is cheaper. The same measure of firewood that is sold in Maiduguri for ₦500 (half a dollar) only fetches between ₦100 and ₦200 in Marte.

Even after making some sales, finding food to buy is another hurdle.

“Sometimes foodstuff will not arrive in Marte even in a week. Sometimes, it will arrive and one cannot afford to buy it. We just have to buy garri and drink with our children,” said the 35-year-old single mother of eight.

Bintu Bukar, 30, who also left Marte recently, told HumAngle households often went to sleep on empty stomachs when they couldn’t get food.

The reason for the scarcity is that the amount of food supplied is not enough to meet the needs of the population. And that supply only comes once — sometimes twice — a week. On Thursdays, sometimes Tuesdays as well. The road is not safe, and those are the days military personnel are able to escort trucks and taxis plying the route. They also occasionally receive supplies on other days of the week when there is an emergency.

“You can’t travel without an escort,” Aisha said matter-of-factly.

The scarcity of various food items has also rendered them expensive. The same measure of maize that is valued in Maiduguri at ₦1,000 is sometimes sold for ₦2,000 in Marte. “We can’t even afford to buy maize,” Aisha clarified. Guinea corn, too, is twice the price. Garri is easier to get, but the price shoots up from ₦700 to about ₦1,000 whenever there is a dip in supply.

I asked her if people adapt by piling up foodstuff in bulk so as to survive the frequent shortages. She replied that this is only possible when people have money to meet long-term needs. They don’t. “There are no jobs there that bring money,” she said.

The aim of the authorities is for the resettled people to achieve self-reliance through agriculture and to revive farming across the state. But this is difficult when terrorists are still waging war in many parts of the region, killing security personnel and abducting civilians. In a lot of communities, the safety of residents is not guaranteed once they venture beyond military trenches. They also have to stop farming in the early hours of the afternoon to reduce the risks of getting attacked. Another challenge is that in places like Marte, locals are prevented from planting certain crops, which, because of their length, would prevent stationed troops from seeing movements in the distance.

“We are only allowed to plant beans, ground nuts and soup plants,” said Bintu. “We only go to farms along Gumalti and Ala. You can’t cross the trenches because there are Boko Haram fighters nearby.”

She mentioned that there have been cases of people getting killed or abducted by terrorists when they advance too deeply into the bush to search for firewood. Among those abducted, some escaped, while others had to buy their freedom. Insurgents also sneak into the town sometimes, disguised as herders, to snatch food items, money, and girls.

“This season’s harvest was terrible,” Aisha added. “Herders pushed their cattle into our farms, destroying the little we could have harvested.” Elephants also trespass on the farms and destroy their crops.

Many parts of Marte are unsafe; according to locals, the only accessible ward is Njine. The resettled IDPs are housed in tents in the Chad Basin Development Authority (CBDA) quarters in New Marte (Gardai), which is the only occupied area of the community. The premise also hosts IDPs from Gubio Camp in Maiduguri and those previously in Monguno and Dikwa.

Though Aisha is originally from New Marte, she still cannot access her home. Many houses are empty, she said. “The governor just hired the houses at the barracks for us. We are waiting for him to return us to [our houses in] New Marte.”

The Borno state authorities shut down nine displacement camps between May 2021 and December 2022, a move that affected over 153,000 IDPs. The government plans to close even more camps around Maiduguri and in other parts of the state, despite criticisms from researchers and civil society organisations who describe the programme as hasty.

Amnesty International has pointed out that many of the resettled communities do not have access to essential services, and the government’s action puts their lives at risk. In an extensive report released in November 2022, Human Rights Watch said the camp closures had pushed many displaced people “deeper into destitution, leaving them struggling to eat, meet basic needs, or obtain adequate shelter”. A few months later, the International Crisis Group reached the same conclusions.

“The government should suspend its camp closure policy in Borno while taking measures to better protect those who have been relocated from harm, including by permitting NGOs to provide them with services and by allowing them to move to places they find more suitable,” the international non-profit advised.

Many in Marte are stranded. They also want to leave like Aisha and Bintu, but it is either they cannot afford the transportation costs or they do not have people in neighbouring towns like Dikwa who can host them. The fare from Marte to Maiduguri, for example, is ₦3,000 for normal taxis and ₦2,000 if you travel in a pickup truck. If you have heavy luggage with you, you pay an extra fee. When Aisha left, she had to pay ₦8,000 for her eight children to move with her. It is impossible to raise that kind of money in Marte, she said. Relatives in places like Maiduguri have to send it to you.

Many of the men and youth have left the resettled community, a local informed HumAngle, with women, children, and the elderly constituting the majority of the population. “The youths and even aged men who stayed behind ventured into drugs because of a lack of means of livelihood. They sit in groups, mostly in locations where charcoal is produced, take drugs and play cards.”

A good number of those who remain in the community look back at their time in Maiduguri with nostalgia. If Bakassi Camp were reopened, Aisha declared, they would have certainly gone back.

Additional reporting by Al’amin Umar.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter