Despite Child’s Rights Act, Violence Against Children Remains Rampant In Northern Nigeria

Though adopted in Nigeria in 2003, some states in the northern region of the country have failed to domesticate the Child’s Rights Act amid rising violent attacks against children in recent years.

Giving legal consent to both the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Child and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of Child, Nigeria adopted the Child’s Rights Act in 2003. The Act is expected to protect children against all forms of inhumane treatment.

While it has been domesticated in different southern states of the country, the Northwest and Northeast states are lagging behind – 19 years after. The states that are yet to domesticate the Act include Adamawa, Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Jigawa, Kano, Kebbi, Yobe, and Zamfara states.

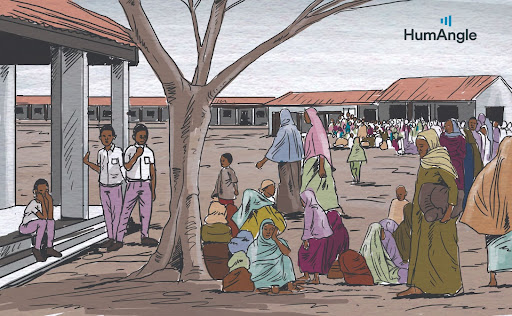

Unfortunately, these states are among the places where insecurity is on the increase, with children being molested and forced into early marriage. HumAngle reported how terrorists have been on rampage, attacking schools and kidnapping students, as against section 27 of the Child’s Rights Act which prohibits the abduction of children.

While some abducted students were killed, many have regained their freedom after months in captivity. Meanwhile, few others are still in captivity. The development has, unarguably, made schools less conducive for learning and, many parents unable to afford the cost of educating their children in northern Nigeria.

In reaction to this, Osai Ojigho, Director of Amnesty International Nigeria said “no child should go through what children are going through now in Nigeria. Education should not be a matter of life and death for anyone. Nigeria is failing children once again in a horrifying manner.”

Already, Nigeria has the highest number of out-of-school children in the world, according to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The northern states, however, have the worst out-of-school children rates in the country as against the provision of section 15 of the Child Rights Act which makes it the duty of the government to provide free, compulsory and universal basic education for them.

Instead of the formal education system stipulated in the Act, the socio-cultural Almajiri system remains prevalent in the north. Many, however, end up on the streets as child beggars, seeking alms and menial jobs for daily survival.

Children have become targets for terrorists as they are being used as sex slaves and forcefully recruited as child soldiers. This also contradicts section 26 of the act which forbids their use for criminal activities.

Meanwhile, section 11 of the Child Rights Act notes that “no child shall be‐ (a) subjected to physical, mental or emotional injury, abuse, neglect or maltreatment, including sexual abuse; (b) subjected to torture, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment; (c) subjected to attacks upon his honor or reputation; or (d) held in slavery or servitude, while in the care of a parent, legal guardian or school authority or any other person or authority having the care of the child.”

Though the law also forbids child marriage in sections 21, 22, and 23, northern Nigeria accounts for 78 per cent of girls who are married under the age of 18, according to data by London-based child rights group, Save the Children International.

In the report released on Nov. 11, 2021, 44 per cent of girls in Nigeria are said to be married before their 18th birthday, one of the highest child marriage prevalence rates in the world. The report said child marriage is more prevalent in the north, where 48 per cent of girls are married before they turn 15 and 78 per cent were married before age 18.

Explaining why domestication of the Act is important in all states, the group said it would provide children with the necessary legal framework for seeking justice when their rights are denied or abused.

Aside from the states that are yet to domesticate the law, southern states where the laws have been domesticated are not showing concrete evidence of change in the lives of children.

A recent example was the public outrage that followed the picture of two out-of-school children shared by Lagos governor, Babajide Sanwo-olu who claimed to have offered them full scholarship. Meanwhile, the fate of the remaining over 2 million out-of-school children in the state remains uncertain.

Rights advocates who spoke with HumAngle said states that have domesticated the Act must ensure proper implementation to challenge others.

Wanda Ebe, founder of Wanda Adu foundation, a non-profit organisation advocating for the rights of children and vulnerable persons said “the federal government needs to be firm and ensure that children have rights. As a nation, we must protect the rights of all children. What is the responsibility of the government when children have no benefit?”

Speaking on the northern states with high rate of insecurity, a human rights lawyer, Supo Adio, said “there is need for specialized programmes to address the peculiar challenges of children involved in the conflict zones and nongovernmental organizations promoting children’s rights should compel authorities to secure the children.”

On the part of the federal government, the Minister of Women Affairs, Pauline Tallen, said in June 2020, that the current leadership has put in place strategies, including advocacy campaigns, to mitigate the hardship faced by children who are victims of aggression, especially in conflict zones.

Two years after her statement, the situation remains appalling as activists insist that every child deserves, at the very minimum, a right to life, protection from harm and right to education.

HumAngle contacted Tallen’s office for comments but did not get a response. Halima Oyelade, spokesperson of the Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs, Disaster Management and Social Development asked this reporter to send a message. She promised to respond adequately to efforts put in place to protect children rights but was yet to do so as at the time this report was filed.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter