Borno IDPs Relocated to Their Hometown of Ajiri Say They’re Worse Off Now

Do they have access to better amenities compared to before their resettlement? No. But at least, is the new environment safer and more conducive for earning a living? Also, no.

There isn’t enough water. The clinic is not functional. And there are frequent terrorist attacks. This is the life internally displaced people have returned to in Ajiri, a small community in Nigeria’s northeastern state of Borno. But it is not what was promised.

The Boko Haram insurgency in the region has led to the displacement of millions of people since it erupted in 2009. Today, more than 2.2 million are still internally displaced — most of them in Borno. Hundreds of thousands more are sheltering in camps across the border in Cameroon, Chad, and Niger Republic. Finding this unacceptable, the Borno state government kickstarted an ambitious programme to reconstruct the abandoned communities and resettle IDPs to their ancestral homes in 2020. It hoped that this would allow the affected people to live “normal lives” and have an “enabling environment” for work. It has persisted on this path — resettling nearly a million people — despite criticisms from several humanitarian organisations that this move endangers the lives of displaced people because of the continued presence of insurgents in the areas. In December 2022, the government successfully shut down the last official camp in the capital of Maiduguri, and it has since set its eyes on displacement camps in other parts of the state.

The people of Ajiri, a community in the Mafa local government area, were resettled in August 2020 amid fanfare. The government had just constructed 500 two-bedroom housing units and ‘temporary clinics’, promising to later build a hospital, befitting school, market stalls, water facilities, and other infrastructure. Each returning household also received ₦50,000, foodstuff, and some non-food items such as blankets, clothes, mosquito nets, and cooking utensils. The atmosphere was full of promise as the authorities urged the returnees to ‘focus on their farming and be self-reliant’.

The governor, Babagana Umara Zulum, visited the resettled community a month later and expressed satisfaction with the situation. He is from the same local government area and feels a connection to the people. “I am happy to see you people living comfortably after your relocation from IDP camps to your ancestral home,” he said. “As government, we will do everything possible to support you.”

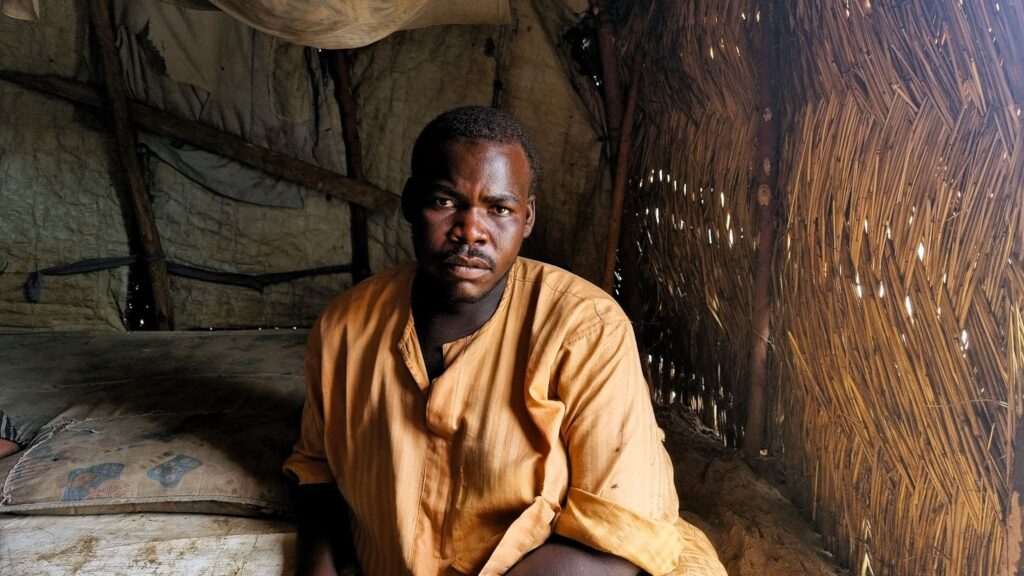

However, infrastructure-wise, not much progress has been made since this time. As HumAngle recently learnt from resettled IDPs in the area, life there is presently full of dangers, hardship, and uncertainty.

Let’s start with the clinic. Because the staff are usually not around, people in Ajiri have to constantly travel about 60 km to Mafa or Maiduguri for medical treatment. If the illness is not severe, they treat themselves at home. “It is not functional, so I can’t call it a clinic,” observed Aisha Dongo, one of the returnees. “They transport the drugs from Mafa. The workers come with their kits to give the drugs and offer treatments. But it is not often.”

Women in labour rely on traditional midwives during birth. If there are any complications, they get transferred to Mafa.

The school is also not a complete success story. Some of the classrooms are said to have no roofs, and teachers are not always available. But a young Mallam has set up a tent near the buildings to take evening Qur’anic classes.

Water is another big challenge. One borehole supplying the town’s thousands of residents is not nearly enough. Aisha said they could go three days without water during the dry season.

Babagana Modu, another returnee, explained that they have to walk several kilometres in the dry months to get water. “There is a tap on the outskirts of the town where we get water. It is very far away. Some people also travel to Mafa to fetch.”

By contrast, Aisha did not face these problems back in Maiduguri because “everything was sufficient”.

The absence of long-lasting peace in communities like Ajiri not only affects infrastructures like schools and hospitals but also means democratic and economic institutions are not able to take root. You can see signs of this during the elections. Last year, for example, the electoral commission announced that it would only conduct elections in ‘super’ displacement camps in seven of Borno state’s 27 local government areas due to insecurity. Some areas did not have elections conducted at all. The distribution of polling units in the state is also grossly uneven. As of 2019, a quarter of the polling units were concentrated in the Maiduguri and Jere areas.

The International Crisis Group observed in 2023 that government support for the resettled communities is not enough to keep them “safe and prosperous”. The absence of government in parts of the state also creates complications for locals, who are forced to interact with insurgents and are then treated with suspicion and targeted by security agents because of this.

The distance between the returnees and the central authorities means they cannot share their grievances easily. In the past, international NGOs have bridged this gap, but they do not have access to many of the affected places either due to insecurity or government restrictions.

“Relocation to sites close to the war front – where residents have little access to the rest of the country, few if any public services and virtually no economic opportunities – risks embittering the people whose lives are put in peril and creating opportunities for the insurgents that the government is fighting,” the think tank concluded.

Aisha is originally from Boskoro, another community in Mafa. She moved to Ajiri after getting married and has lived there longer than anywhere else. She became displaced about a decade ago when the frontlines of the insurgency stretched to Ajiri. At first, Boko Haram terrorists disturbed their peace. The terror group shot many people in their homes, including community and spiritual leaders. The locals would flee to safety whenever they attacked and return when the dust settled. But when they were caught in a web of fierce gunfire and air strikes between state and non-state actors, they realised they had to leave permanently.

“They [Boko Haram] had a fierce battle with the military one day, making the military set the town ablaze,” Aisha recalled.

After days of travelling on foot, the displaced townspeople finally arrived in Maiduguri. It was extremely tough at first.

“My husband was arrested and taken to the barracks, where he died. My son was also later arrested, but he got freedom after five years. We first stayed at Goni Kachallari when we arrived. There were seven orphans under my care at that time. From Goni Kachallari, we came here [Muna Garage camp]. We had nothing to eat and no job to do. We tried farming, although the land did not belong to us.”

Less than three years later, they returned to Ajiri. But Boko Haram continued to attack. The town could not sustain any meaningful existence, so they left again. Some young people would continue to go for farming and construction jobs, but life was generally harsh in the community.

Many years passed before the issue of resettlement came up again.

Aisha was particularly happy when the state government announced this plan because she thought they would finally be able to return to the farms and rebuild their lives on a strong foundation. But even this has not materialised. There have been “a lot” of Boko Haram/ISWAP attacks on the community since the resettlement — one taking place only four months later in December 2020. In May 2021, there was another brutal attack that led to the death of over a dozen people, including civilians, soldiers, and vigilantes. The insurgents also set fire to houses before leaving. Such attacks are not uncommon in resettled communities across the state.

Aisha recalled that the first time the terrorists came around, they merely patrolled the area between 5 and 9 p.m. and then left.

“They, however, killed seven people on their second coming. Another seven were killed in the attack that followed. They burnt several houses. I counted six houses. But it is more than that.”

She added that the last time they attacked was only three days before the interview in August 2024. They had targeted the military personnel and did not proceed into the town.

“And at night, curfew starts by 8 p.m., but people still get to sit at the front of their homes or have audible conversations at home. However, once it is 10 p.m., everyone goes indoors and remains quiet. The military and Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) then patrol the town,” she stated.

Babagana confirmed that the nights in Ajiri “are always chaotic and scary”.

When he was in Maiduguri, he sold household items. So, he continued this trade after he resettled. But then Boko Haram terrorists looted his shop when they attacked. He sourced money to restock, but they came again. And this time, “they burnt the shop — all the shops there.”

He gets by now by going to Maiduguri to work as a farm labourer.

“They come randomly and frequently,” he said about the attacks. “The military often flee while they go in to kill people. I really can’t count [how many times they have come since the resettlement], but there were many attacks. They come at night and day.”

The frequent attacks mean the residents are not able to farm whenever they want. It is also difficult to access the farmlands because of the shortage of taxis. When they can, they go in the morning and return by midday to avoid getting attacked.

While farming has not proved to be a dependable livelihood, trading is not a great alternative, either. There is no respectable market. Retailers only travel to Mafa to buy products in small quantities. When they sell, they close shop before sundown because “everyone is afraid of attacks”.

“On days we are able to gather firewood and sell, we would get to buy food items to cook. And if we cannot go out, we stay hungry. We often feed on plain spinach leaves and sometimes garri or maize flour,” Aisha narrated.

Unfortunately, the danger of getting attacked and killed does not only come from Boko Haram terrorists. When she introduced herself at the start of the interview, Aisha mentioned that she had eight children before quickly correcting herself and saying seven. The reason would come to light later.

In February, a soldier shot a rocket-propelled projectile towards an area where six civilians were seated. Three of them died. The other three sustained injuries. One of those killed was Aisha’s son, 20-year-old Shuaibu.

“He was fighting no one. No one saw any attack or knew why he fired. We just heard a loud noise,” she said. She added that the soldier was not held accountable after this incident, but he would later be killed during a terror attack.

Babagana’s brother, Goni Modu, was one of the victims as well.

Babagana estimates that about a thousand people live in Ajiri town and about a thousand more in the surrounding camps. There used to be more people, he clarified, but they left because of the thorny situation. Younger people especially have a tendency to seek out safer places with better opportunities.

“It would be a good thing to be back in your community. However, the lack of livelihood and insecurity is a challenge. In Maiduguri, you can get to do some work. There is nothing to do there.”

Asked why anyone would want to move to Ajiri in these circumstances, Aisha replied sarcastically. “Maybe to enjoy the hunger and suffering there?” So, if she knows this, how come she hasn’t left? Well, she explained, that is because the local authorities keep telling them their sacrifice is necessary to restore the town to its glory days. Normalcy will not return if they do not remain, they say.

What does normalcy look like? Babagana described the town he used to know before the insurgency started. It was great, he said. “It was so peaceful and accommodating that when outsiders come, they wouldn’t want to leave.”

He would like to see that Ajiri again soon.

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center as part of a series interrogating the state of democracy in some of Nigeria’s resettled communities.

The return of internally displaced people to Ajiri, Borno State, Nigeria, has been fraught with challenges, contrary to government promises. Despite efforts to rebuild the community with new housing and temporary clinics, the situation remains perilous due to scarce water resources, a non-functional clinic, and frequent Boko Haram attacks. Infrastructure is underdeveloped, with schools incomplete and residents lacking basic services.

The resettled population faces constant threats, unable to farm or trade effectively due to insecurity. Younger residents often leave in search of better opportunities, and democratic processes are disrupted by the persistent violence.

Government support is inadequate to ensure safety and prosperity, forcing locals into precarious interactions with insurgents. Despite this, authorities claim maintaining residency is essential to restoring the town, drawing on past memories of peace and community.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter