Blockage of Biafra Memory Websites Highlights Disturbing Pattern in Nigeria

Before digitalising history, Biafran stories survived in recollections passed down like secret heirlooms. Digital initiatives, such as Chika’s, made the stories more accessible, until Biafra's history required a VPN to be accessed.

She did not know her mother was a Biafran refugee until she was about 18 years old. They were watching footage of famine devastating refugees in the Middle East from the comfort of their home in the United States when her mother told her. From that moment, she became more curious about her origin, history, and the Biafran story.

Many years later, Chika Oduah, a Nigerian-American journalist, became an archivist, documenting the reminiscing stories of the Biafra war. She called it the Biafran War Memories, a digital archive of personal stories and first-hand accounts of the 1967-1970 Nigerian civil war. She had been inspired by how historians memorialised the Holocaust, the massive state-sponsored killing of the European jews during World War II. The journalist-turned archivist loved the rigour and energy poured into the documentation of the genocide, and wanted to replicate the same with the Biafra war.

“That’s what I’m doing with Biafra War Memories. These stories cannot be lost,” she said during a recent interview. “That war is part of world history. And that’s what I want people to understand. It’s not just Nigerian history, this is world history, and museums have asked me to put some of that information in their museums.”

The idea flew above the sky in 2017, gaining the attention of those interested in the history of Biafra, especially the human cost of the civil war and what the lives of the witnesses and victims looked like decades after it ended. In 2019, for instance, Oby Ezekwelisi, Nigerian human rights activist, posted on X about the archiving initiative: “Here is @chikaoduah’s work #BiafranWarMemories. It is a quick video explainer on the project. So far, Chika has interviewed more than 150 people and has added these interviews to www.biafranwarmemories. Incredible work of documentation.”

However, the website has been locked behind a digital barrier, with the Nigerian government restricting access to it. Until a Virtual Private Network (VPN) is deployed, Nigerian readers can’t have unfettered access to the website, on most service providers, posing a threat to visibility for years of research, on-the-ground interviews, and the general efforts to produce the work.

The Biafra memory lane

The civil war that shook Nigeria from July 6, 1967, until January 15, 1970, is described as the Biafra War. The eastern region decided to secede from Nigeria to form a separate, independent country, the Republic of Biafra, under the control of Lt. Colonel Chukwuemeka Ojukwu. In 1966, two major military coups caused a widespread anti-Igbo campaign, breeding political unrest, ethnic violence, and economic tensions, with the Igbos accusing the federal government of marginalisation.

The armed conflict ended gorily, killing between 500,000 and two million civilians due to an alleged food blockade, which caused massive starvation of the Biafran people. After the three-year-long deadly war, the Nigerian government adopted a slogan of “no victor, no vanquished” to suggest that no party won or lost the battle.

Many years later, the grief from the losses and bloodshed grew into grievances over allegations of marginalisation in the political space, with many Igbos believing they were disadvantaged. The agitations culminated in pro-Biafran movements, with Nnamdi Kanu founding the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) in 2012. Kanu campaigned for the restoration of Biafra; he has since gained support among Igbo youth who feel sidelined in Nigeria’s political formation.

The Kanu-led IPOB would later turn violent, spilling the blood of unarmed civilians, waging war against Nigerian security operatives and grounding economic activities during mandatory weekly sit-at-home demonstrations. The group deployed mass rallies, media campaigns, and Biafra Radio as a medium to establish widespread dominance, gathering influence and control among the agitated people. The Igbocentric campaigns, encompassing rhetoric and mobilisation, conflicted with the Nigerian authorities, who later saw IPOB as a national security threat, declaring the group a terrorist organisation in 2017.

Amid the federal government’s proscription of the secessionist group over widespread violence in southeastern Nigeria, archivists emerged, focusing on documenting the forgotten stories of the Biafra war. Before digitalising history, however, Biafran stories survived in whispers, in recollections passed down like secret heirlooms. But digital initiatives, such as the Biafra War Memories, made the stories more accessible until the archiving websites required a VPN.

Locked behind digital barriers

When Chika updated her followers about the website’s blockage, an X user corroborated her claim, sharing a similar experience. “We noticed this earlier this year and had to change our domain and name. All domains with the word “Biafra” are blocked in Nigeria,” the X user, bearing the War Archives, claims. Described as the digital repository of the Nigeria-Biafra civil war, the War Archives is similar to the Biafra War Memories. The website only came back to life after changing the domain name and removing the word “Biafra”.

HumAngle explored the War Archive website and found dozens of stories preserving war memories and documenting personal anecdotes, photographs, and artefacts, among other things, of the Civil War. The website, for instance, has a memorial page revealing the names of hundreds of civilian casualties of the Biafra war and honouring “the lives tragically taken during those turbulent times.”

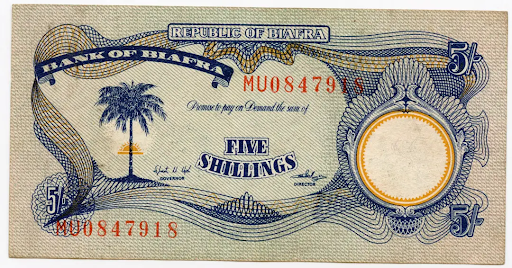

War Archive documents an extensive array of digitised ephemera, photo collections, relics, and historical documents meticulously curated from the Civil War era. Some collections include photos of a military uniform belonging to a Biafran soldier, a five-shilling note of the then Bank of Biafra and pieces of memorandum and classified documents related to the war.

Had the War Archive not changed its domain name, these historical gems, like Biafra War Memories, would have been hard to reach on many service providers. It was not the first time authorities would block pro-Biafra websites, citing national security, hate speech, and misinformation as their reasons. In November 2017, for example, over 20 websites were restricted and denied access on most service providers in Nigeria. It was revealed that service providers had blocked the websites, including the popular Naij.com news outlet (now known as Legit.com), at the request of the telecommunications regulator, the Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC).

The injunction to block the websites was issued at the request of the former national security adviser. Many of the websites were alleged to advocate for the independence of Biafra. Some digital rights advocates condemned it, arguing that the process lacked transparency. However, the NCC maintained that the decision was made per Section 146 of the 2003 Nigeria Communications Act (NCA), which mandates that Internet Service Providers (ISPs) work with the NCC to safeguard national security and combat crime.

A 2018 report by the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) and the Paradigm Initiative, a digital rights hub in Nigeria, revealed the Nigerian government’s methods for restricting or blocking pro-Biafran websites. The Digital Rights Institute reports that the Nigerian internet service providers appeared consistent in the types of censorship techniques they adopted.

“The measurements that show ‘generic timeout errors’, ‘DNS lookup errors’, and ‘connection errors’ present signs of network anomalies. However, they do not necessarily serve as evidence of internet censorship, since they may have occurred due to transient network failures. While Globacom, MTN, and Airtel appear to block the same sites on the exact dates consistently, it’s worth noting that Airtel did not block two sites (ustream.tv and bafmembers.com) that appear to have been blocked by Globacom and MTN,” the report asserts.

“This approach may be advantageous since using unrouted IP addresses for blocked domains prevents clients from generating additional traffic, which could potentially overwhelm their network,” the report adds.

The digital rights experts who conducted the research confirmed that, in assessing internet censorship in Nigeria, the absence of blocked pages complicates the identification of intentional website restrictions. Nigerian internet service providers typically do not provide block pages, making it difficult for researchers to attribute website inaccessibility to censorship rather than technical issues. Organisations like OONI have had to rely on long-term network measurements to identify persistent interference patterns.

Significant limitations exist, including a lack of recent testing; the last comprehensive analysis occurred on April 25, 2018, with substantial gaps in monitoring since November 2017. Despite these limitations, evidence from the April 2018 tests strongly suggests that many initially flagged sites were blocked. Out of 21 sites analysed, 20 showed clear signs of network interference, while other provocative websites remained accessible, indicating deliberate censorship.

The observed network anomalies, like TCP/IP blocking, DNS tampering, and HTTP interference, were consistent across multiple ISPs, further supporting the argument for intentional censorship rather than random technical failures. The uniformity of blocking techniques across providers suggests systematic censorship targeting specific websites. Overall, while acknowledging certain data limitations, the consistency and extent of network interference observed strongly support the hypothesis of targeted internet censorship in Nigeria.

“As we have said before, blocking the domain names of or restricting access to websites is a brazen violation of the right to freedom of expression as guaranteed by the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria and international instruments to which Nigeria is a signatory. The Federal Government has to protect free speech, not curtail it,” said Sodiq Alabi, a digital rights activist, on the Biafran website blockage at the time.

“What does this development mean for digital rights in Nigeria? If the government can just wake up one day and restrict access to a website, what does that mean for the digital economy? What does that mean for democracy and Nigerians’ ability to criticise the government and voice their dissatisfaction with an administration they disagree with?” he asked.

Removing grains from chaff

It is easy to describe some blocked websites as the disinformation arm of the IPOB agitation. Some of them were, in truth, used to spread unverifiable information or inflammatory stories, but the Biafra War Memories seems distinctive in its archival approach. Although the archiving website was not among those officially blocked in 2017, experts have said the government might have used the same pattern to cut the project off the internet.

When HumAngle explored Biafra War Memories, we found scores of stories of people who witnessed the civil unrest reliving their experience in the digital age. Many of them kept the stories within the confines of their families, friends, and relatives for decades, but this project unearthed them. One victim, Christopher Ayogu, described how Igbos were brutally killed at the time, claiming that “civilians who don’t know anything about what is happening were just being murdered”. Another soldier, Nnamdi Onwualu, spoke about how, as a student, he turned into a soldier overnight during the war.

“I went into the war a boy and came out a man,” Onwualu recalls, as archived. “[When I think about the Nigerian-Biafran War,] what comes to my mind is a lot of things, a lot of things. The disturbances of 1967. The killings in the North that precipitated the war. It was a very traumatic time. I lost my father and my grandfather during the war. I lost many friends also during the war.”

Interestingly, Donatus Nsionu, another Biafran soldier, narrated how he drank his urine and excreted maggots after joining the war as a fighter. His experience is gory, but it creates a vivid picture of the tragedy that befell people during the war. He hasn’t moved on from the pain and agony that came with the war, many decades later.

“The Nigerian soldiers didn’t kill me. But I killed people — many people — because I was well trained. I took my training seriously. I didn’t chase women on the battlefield, and I didn’t steal from anyone,” Nsionu says. “I only fought those who said I couldn’t return to my father’s land. They were the ones I confronted. I hope you understand me. A single bullet didn’t hit me, but I don’t even have ten naira to my name. Ten naira. They never paid me before the war ended.”

The platform also documents historical stories from other websites, such as a piece revealing Israel’s secret mission to save lives during the war, and a HumAngle in-depth analysis into the evolution of self-determination movements after the Biafra war. Chika was loud about the Biafra War Memory project; her intention was made clear several times. During an online conversation with a Nigerian writer and YouTuber, Rudolf Okonkwo, she shared her thrilling moments while interviewing over 100 people who witnessed or participated in the war.

“I’ve spoken to journalists who covered the war. I’ve spoken to, of course, Biafrans. I’ve spoken to Nigerian military personnel. One Nigerian military personnel I interviewed from Plateau State broke down and cried, talking about how he lost his brother on the battlefield,” she says.

Digital rights activists and experts are divided on this issue. While some agree with blocking Biafra-related websites, others believe that authorities should be able to remove the grains from the chaff. Some analysts argue that some Biafra-linked platforms have been used to spread disinformation, incite violence, and target other ethnic groups. A report by the Disinformation Social Media Alliance, for instance, highlights how these sites have hosted content that includes genocidal threats and hate speech, prompting calls for stricter enforcement of Nigeria’s Cybercrimes Act of 2015.

On the other hand, the digital advocacy group warned against blanket censorship, noting that, while hate speech must be addressed, the removal of websites risks infringing on constitutionally protected freedoms of expression and association.

Chika Oduah, a Nigerian-American journalist, created the Biafran War Memories digital archive, inspired by how historians documented the Holocaust. She aimed to make the personal stories of the 1967-1970 Nigerian civil war widely accessible. However, her website faced access restrictions by the Nigerian government, citing national security concerns around pro-Biafran content, necessitating the use of VPNs for access.

The Nigerian civil war, or Biafra War, arose from ethnic tensions and political unrest leading to the secession attempt by the Republic of Biafra. The war caused significant casualties and starvation due to blockades. Despite the conflict ending with a "no victor, no vanquished" policy, grievances persisted, leading to the formation of groups like IPOB, which became a focal point for renewed agitations and conflicts with government authorities.

The Nigerian government's approach to blocking websites associated with Biafra, including the use of consistent censorship techniques by ISPs, has sparked debate about digital rights, with critics arguing it impedes freedom of expression and access to historical information. The debate highlights the need for a nuanced approach that balances combating disinformation and preserving public access to critical historical records.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter