BBC Documentary Unravels The Many Layers Of Violence In Northwest Nigeria

Why have a people known to live together for many years suddenly turned against each other? What is the impact of this crisis on ordinary people who just want to get by? And what are the authorities getting wrong in trying to resolve it? BBC Africa Eye answers these and other questions in a new report.

Many communities in Northwest Nigeria that used to be known for their agricultural exploits, educational facilities, and cultural trademarks, or even unheard of, have recently become landmarks on the map of violence. In the last 10 years, a new form of insecurity has settled into the region, seizing the innocence of children and the peace of adults, taking lives, destroying homes, and displacing hundreds of thousands.

Those at the root of the violence have gone by several names: bandits, militias, killer herdsmen, terrorists. And they belong to scores of different armed groups, each with its leaders. But their methods share the same levels of brutality.

Often, when the events are reported, it is mainly from the point of view of one or a few of the actors. But in an hour-long documentary released on Monday, The Bandit Warlords of Zamfara, BBC Africa Eye shows the different sides to the story.

“The ensuing nightmare has killed thousands, closed hundreds of schools, and is spreading into neighbouring states. Massacres and mass abductions are frequent,” says reporter Yusuf Anka while narrating. “But this conflict defies simplistic interpretation and remains underreported. It’s just too dangerous. So Nigerians’ questions go unanswered. Who are these bandits? What do they want?”

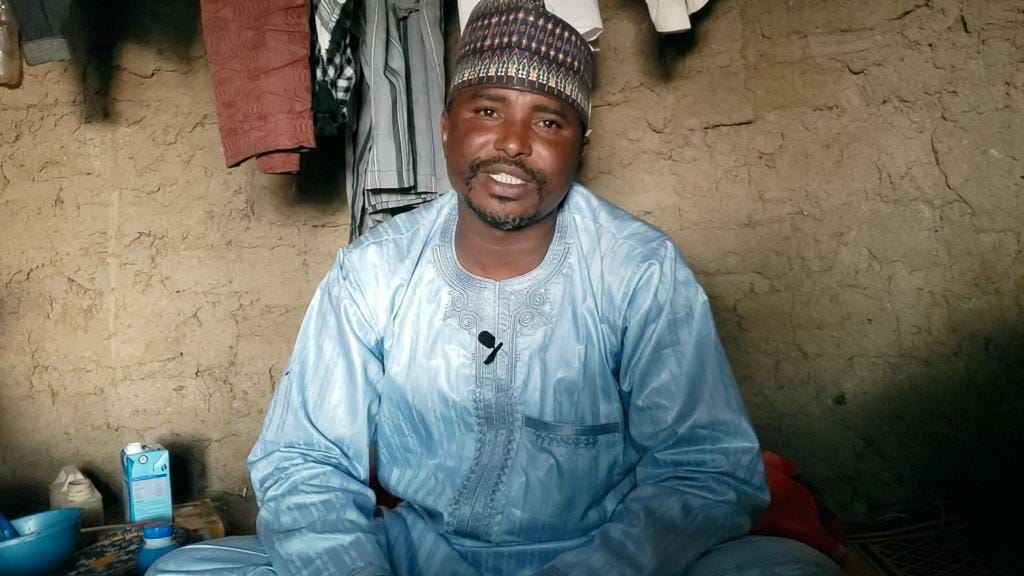

Anka did not only attempt to answer these questions through interviews with various ‘bandit warlords’, but he also dwelled extensively on the experiences of civilian victims. He captures their frustrations and shares their tragic experiences in graphic detail. To do this, he had to visit remote communities and the forest enclaves of the armed groups.

The report is enriched with footage shot by members of the terror gangs among themselves, including one that appears to show evidence of their abuse of hard drugs. There are also videos from community residents and travellers filmed during and immediately after attacks, which all make clear the severity of the situation.

The documentary indicates that the fatalities from terror attacks in the region have been underreported many times. In one instance, the government stated that 58 people died during an attack in Kurfa Danya, a community in Zamfara. But the locals maintain that over 200 people were killed as they point to the mass graves.

More people are itching to defend themselves against the onslaughts, but the state authorities are averse to the emergence of self-help militias and unregulated vigilante groups.

Growing anger and tension are also giving rise to extremist tribal sentiments and inter-ethnic clashes. “If allowed, we will kill every Fulani man, even in the town. Because they killed our mothers, our fathers, our children, and dumped their bodies here,” one resident of Kurfa Danya tells the BBC.

This is despite the fact that Fulani people have been victimised by the terrorists too. Now they face attacks on multiple fronts due to ethnic profiling and the ruthless approach adopted by vigilantes. Already, Hausa people are indiscriminately attacking their Fulani neighbours, including women and children, because of the crisis.

So what do the bandit warlords want and what are their grievances?

Granting a press interview for the first time, Ado Aleru, one of the most notorious warlords, says they did not know journalists they could share their problems with and only know to protest using guns. By attacking villages, they hope to draw the government’s attention and get it to address their complaints, he said.

His associate highlighted the encroachment of cattle grazing routes, air raids, the lack of veterinary clinics and drinking water sources, and alleged anti-Fulani marginalisation as parts of their grievances.

Some of his outrageous comments show that disinformation is one of the lesser-known drivers of the conflict.

“Many Fulani have university degrees. The government never considers them,” he claims passionately. “I swear, if 1,000 Hausas sit an exam alongside a single Fulani man, they will pass all the Hausas and fail the Fulani man … If you see Fulani resorting to so-called terrorism, it’s because of this.”

The BBC report suggests that resolving the crises will require first understanding that different groups of people contributed to escalating it and, therefore, have roles to play.

“Everyone, the Fulani and the Hausa, has done something wrong,” says Hassan ‘The Rebel’ Dantawaye, a former terror commander. “For the Fulani, there’s one. Retaliation is their major problem, while the Hausa don’t investigate who is guilty or innocent. You have policemen, soldiers, governors, local chairmen, and councillors, no one is stopping this situation.”

One troubling development emphasised is the rise of a younger generation of militants who have known nothing but violence all their lives.

“Fulani and Hausa people have two major problems now,” observes Hassan The Rebel. “We have primary schools in our villages, but they are not functioning now. We are producing an illiterate generation. Tell me, how can an illiterate person know right from wrong? We have now reached a point where there are some that don’t know the meaning of peace. They were born in conflict. What do they know of peace when 10 years of their lives are spent in a war zone?”

These younger fighters, he says, do not understand that stealing and other crimes are wrong and see the insurgency as a business. There’s a similar development in the Northeast, where Boko Haram and the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) are also brainwashing child soldiers and deploying them frequently in battle.

For now, nearly all the groups are guilty of monetising the conflict. For example, though the government had insisted no ransom was paid, Abu Sani, one of those behind the Feb. 2021 abduction of 279 schoolgirls in Jangebe, says they were paid ₦60 million ($144,490) after negotiating down from ₦300 million.

“If the bandits of Zamfara want to hurt the government, they also want to make money,” Anka confirms.

It is this ‘terrorism-as-a-business’ approach that makes it difficult for the conflict to end, says Abu Sani, and it is not only because of the militants’ greed.

“Everyone wants money. That’s why things are deteriorating. From the top to the bottom. They say when there’s insecurity, the government gets money. Everyone is benefitting. We also get money. Though, for our money, blood is spilt. So it continues.”

Another important detail in the report is the terrorists’ hostility towards public education, but not to such an extreme extent as the northeastern Non-State Armed Groups. Though they threatened the Jangebe schoolgirls that they would kidnap them again if they returned to school and described western education as useless, some of them were willing to learn from the girls who attempted teaching them what they learnt from their classes.

“We started teaching them but they found it too difficult, and we had to stop,” says one of the girls, who remains enthusiastic about continuing her education.

The documentary further draws attention to the different ways the government’s handling of the crisis is lacking, from a pattern of poor emergency response to air bombardments that affect civilian residences and alleged indiscriminate raids of Fulani communities by soldiers.

The government appears to have also lost touch with the sensitivities and realities of the people.

For example, following the release of the Jangebe girls, they were kept in a hall and required to listen to hours of speeches from politicians as their families waited impatiently outside. Eventually, the parents stormed the venue and demanded to leave with their children, especially considering that many of them still had to travel far distances and it was getting dangerously dark. As they protested, soldiers shot at the crowd, killing one boy, sibling to one of the released schoolgirls.

“The family got their daughter back, but lost a son,” Anka says in his narration.

The Bandit Warlords Of Zamfara has received widespread acclaim since its release, with many experts hoping it would promote a better understanding of the crisis while helping the government resolve it. “I took this risk in efforts to help understand this decade-old violence as a step to fighting and ending it,” Anka himself tweeted on Monday.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter