A Missing Father, Six Daughters And A Struggling Wife

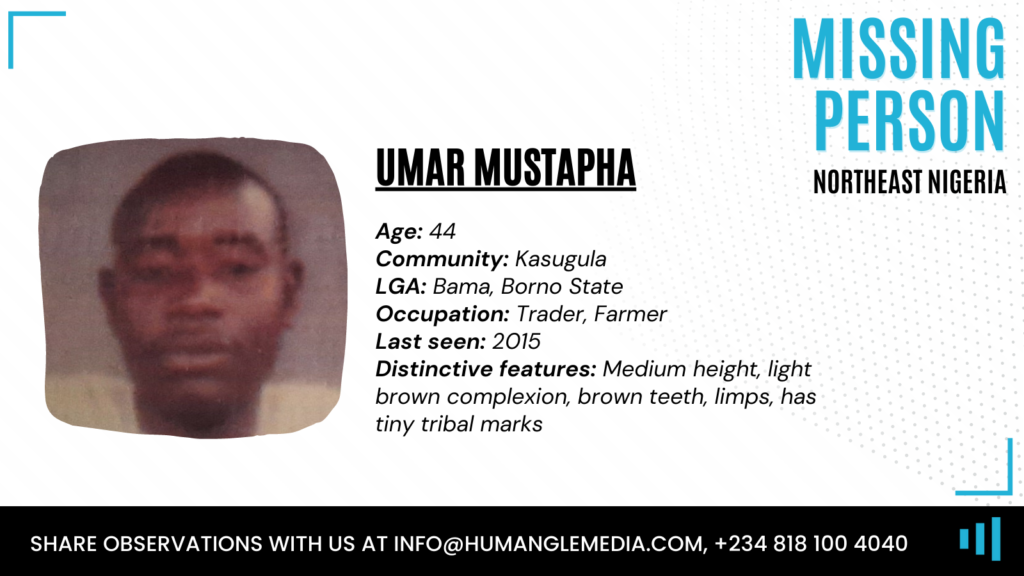

One afternoon, Umar left a displacement camp in Adamawa to make ends meet, as he usually did. Over seven years later, he still has not returned and his wife and daughters miss him beyond measure.

“I would be very happy. I would be happier than you could ever imagine. I would hit my legs against a tree, and the tree would break apart.”

Aisha Umar, 40, laughs heartily as she makes a snapping motion with her hands to indicate the unlucky tree’s rupturing. She is describing what would happen the moment her husband finally returns to her. The thought had immediately filled her with joy. Her smile stretches so broadly it reveals her teeth, and then, as if embarrassed, she moves to cover her mouth with her right hand.

“There would be no sleep that night,” she says, still beaming.

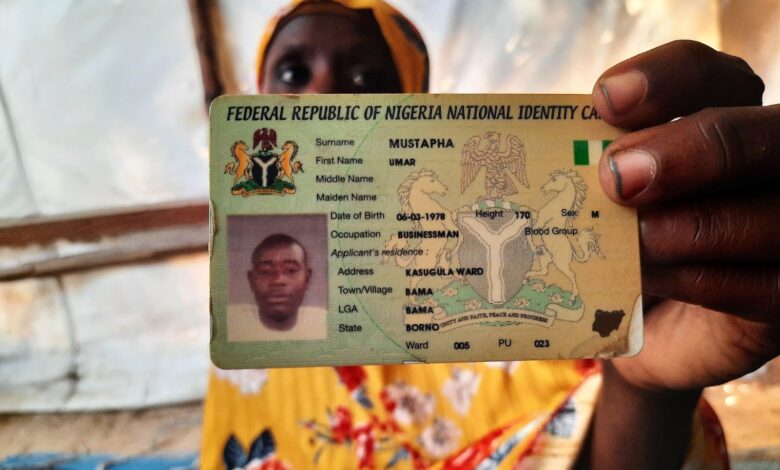

Aisha and Umar Mustapha, 44, have been married for over 25 years. But for about a third of that period, she has not set eyes on him and has no clue where he might be. Or whether he is even alive.

When the devastation caused by the Boko Haram conflict in northeastern Nigeria is discussed, immediate mention is sometimes made of the over 36,000 people who have lost their lives to protracted violence. Yet, another class of victims, also running into tens of thousands, is hardly talked about: people whose whereabouts are unknown and who have mysteriously disappeared.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) says it has documented over 24,000 missing person cases, most of them connected to the insurgency. This is more than half the number of people recorded as missing across Africa. Yet, the humanitarian organisation says the figure “is only the tip of the iceberg and the full scale of the humanitarian fallout in Nigeria remains largely unknown.”

For Aisha and Umar, it all started in Kasugula, a ward in Bama town, Borno State. The couple lived around the Mammy Market area.

The vicious terror group, Boko Haram, had spread its tentacles beyond Maiduguri, the capital of Borno where it first maintained a stronghold, to other parts of the region. In the first week of Sept. 2014, the insurgents invaded Bama town, about 70 km southeast of Maiduguri. Arriving in armoured trucks, they engaged the military forces and eventually seized control of the community, holding on to it for at least the following six months.

Even in the years before this time, the community was a danger zone. People were killed in their dozens. Women and children were abducted. Men were forcefully conscripted. Businesses ground to a halt.

“Boko Haram would come and kill someone and, after that, the soldiers would also come and shoot people. They once killed someone in front of our house and another person at my neighbour’s house,” Aisha narrates. She whips out certain words loudly and sharply to underscore how intense the violence was. The person killed opposite their house was a young man they called Alhaji Sayina. The murdered neighbour, Ari, was Umar’s cousin.

“Also, Boko Haram was about to start abducting girls. All those things made us to move because we suspected something like that would happen. Because we have girls, we worried that if we stayed, this thing would happen to our girls.”

The family travelled half a day on foot to Banki, which lies just across the border from the Far North Region of Cameroon. Then they crossed into the neighbouring country, first settling in Kusuri.

One day, the authorities gathered the refugees in DAF trucks that conveyed them to Adamawa, which shares boundaries with both Borno in the north and Cameroon on the eastern side. The journey back to Nigeria was distressing.

Aisha says 21 women and children in the truck trailing their own died due to heat and congestion.

The refugees spent two difficult weeks in Sauda, a border community between Adamawa and Cameroon, and had to sell their belongings to survive. Then another batch of trucks took them to a displacement camp in Fufore, half an hour’s drive from the state capital, Yola. It was about three months after Muhammadu Buhari was sworn in as Nigeria’s president, so it must have been sometime in Aug. 2015.

Aisha and Umar stayed here for close to six months before tragedy visited.

Umar used to leave the camp environment for the town in search of work. Every day, he would leave in the morning or afternoon and return in the evening. Until he didn’t.

“We started searching for him in detention centres because we thought he was arrested,” Aisha says.

But the month-long search was futile. Eventually, towards the end of 2016, the government closed the Fufore camp and facilitated their return to Borno State. Aisha continued the search for her husband in Maiduguri, where she quizzed people who had been released from detention. Nobody had seen him.

“Up to now, we don’t know, maybe he was arrested or hit by a car. We went to hospitals too but didn’t find anything.”

When people displaced by the insurgency go missing, it usually happens as they are scampering to escape from danger, during encounters with security personnel, or as they search for jobs, as in Umar’s case, or places to stay.

Umar is averagely tall. He has small eyes, light brown skin, tiny tribal marks, and brown teeth from his habit of eating kola nuts. Aisha seems to have a zigzag patch of brown lining her upper teeth. She says her lover also has a scar on his lower back, lifting her bright yellow hijab to point at the area. It was from a motor accident.

He also started limping after a snake bit him on the farm sometime around 2005.

Aisha was a divorcee when she married Umar. Originally from Bulumkutu, Maiduguri, she had met him during a visit to Bama. They currently have six children.

Umar sold chickens in Bama after buying them during trips to neighbouring towns such as Banki, Boboshe, Dikwa, and Walasa on their market days. He had a farm where he planted beans and guinea corn when the season was right. During his leisure time, he loved to go hunting.

Aisha’s excitement seems to peak anytime she talks about Umar’s hunting exercises. Her face glows once again, and she gesticulates more passionately.

“He used to bring rabbits and other things,” she says. “He went with sticks and dogs. One time, he came home with the dog but his mother did not like it. She said she did not want to stay with dogs. So he kept the dog outside with his friends.”

Asked what her favourite things about Umar are, Aisha smiles, adjusts on the plastic mat, leans forward, and then asks quietly: “Is it not between husband and wife?”

But there are other details she can share, such as how whenever she asks for something that he cannot afford, Umar would reply that ‘this is what we have and this what we can do.’ And whenever he had the means to, he gave her anything she needed.

“I like him because he is too sincere. He always told me the truth. Second thing, he was always concerned about his family in all matters.” He was generous with his friends too, always sharing with them part of his hunt. “Even food,” Aisha adds. “Anytime we cook, he would say, ‘Let me go and share this with my friends.’”

Now that he’s not around, things are not the same. The children have been affected the most. Ten-year-old Makkah, the second to the last, frequently cries because she misses her father.

“We had to go to a Mallam. He wrote some [Qur’an] verses and we gave her, then she calmed down. But up to now, she does not keep quiet,” Aisha says.

Sometimes the girls would point at someone who resembles Umar and she would have to convince them he is not the one. “Makkah will say that man coming is my father. I will be the one to say, ‘Sorry, Makkah, it is not him.’ And I will beg her that we should go.”

With all of Aisha’s children being girls, she has had to be more eager in pushing two of them into marriage to lessen the burden of providing for the family’s sustenance. The rest help in sewing caps, which they sell to be able to buy food and other essential items. Sometimes they work on people’s farms. Sometimes they resort to begging. Sometimes they don’t have anything to cook and spend entire days without food.

“This is the way we suffer,” Aisha wails.

One thing she is grateful for is that the children attend school at the displacement camp, though they are not able to advance beyond the basic classes because she does not have the resources to enrol them. At least, she says proudly, they can write their names. “They are better than me.”

Aisha wants the government to help her in locating her husband. It is very important to her. Constant worry about him, especially at night, has caused her to lose weight, she says.

“I am begging the NGOs, if they are able to search [for Umar], they should search. They should help us. If we get any information from them, we will be happy. We need help. From the government too, we need help. We don’t have anybody, only the government.”

But reuniting with her husband is not the only thing she worries about. She still has four girls to take care of by herself.

“We don’t have food to eat,” she says with a solemn look and voice. She used to get between ₦17,000 and ₦18,000 ($43) monthly from the World Food Programme (WFP), but the aid was stopped around June last year.

“Last week, in my house, for five days we didn’t cook. On the fifth day, my daughter Falmata had become weak and looked like she was going to faint because of hunger. I had to go and sell my aluminium pot. Then I bought one kilogram of rice and some beans. My neighbour saw our condition, so he brought food for us to eat. I have to request pot now from my neighbours before I’m even now able to cook. This is the situation we are in.”

If Umar were around, she is sure it would make a huge difference. He would find a way to provide for the family, maybe through farm work or fetching firewood. He had always been industrious. When the family was in Kusuri, Cameroon, he had earned some money from riding a motorcycle.

“If I could send him a message, I would send him my regards and tell him we want him to return,” Aisha tells HumAngle. “We are here alive and are always thinking of you. If you are well, we are well and excellent. May God answer our prayers so that we will reunite.”

This report was produced in partnership with the Open Society Initiative for West Africa (OSIWA) under the Missing Persons Register’s Population and Amplification Project.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter