A Father And Daughter Went Missing, Then Worse Things Happened

Having somehow vanished in the chaos that followed their displacement, their absence has not only been a devastating experience for the family but a fatal one.

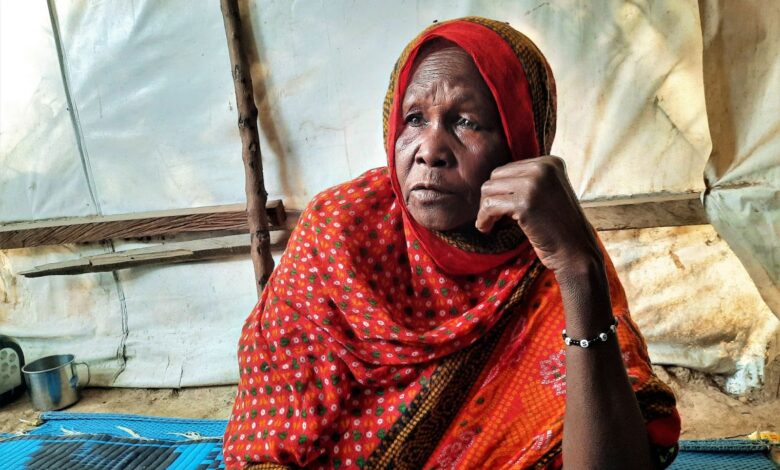

The night Amina Amodu, 60, thought would mark the end of one lingering tragedy ushered in the beginning of yet another.

Members of the terror group, Boko Haram, had plagued Kumshe, her hometown in Bama, Nigeria’s northeastern Borno State, and were actively recruiting. Amina and her husband, Amodu Butu, were worried about their children’s safety. They also feared that during an inevitable military raid, the troops might not discriminate between the terrorists and civilians when they aimed their firearms and dangled their cuffs.

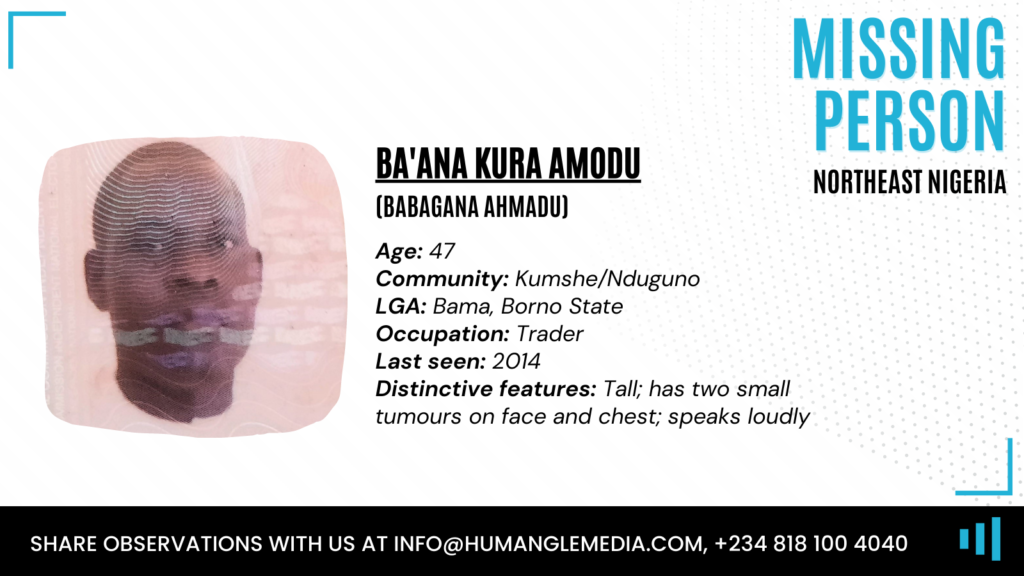

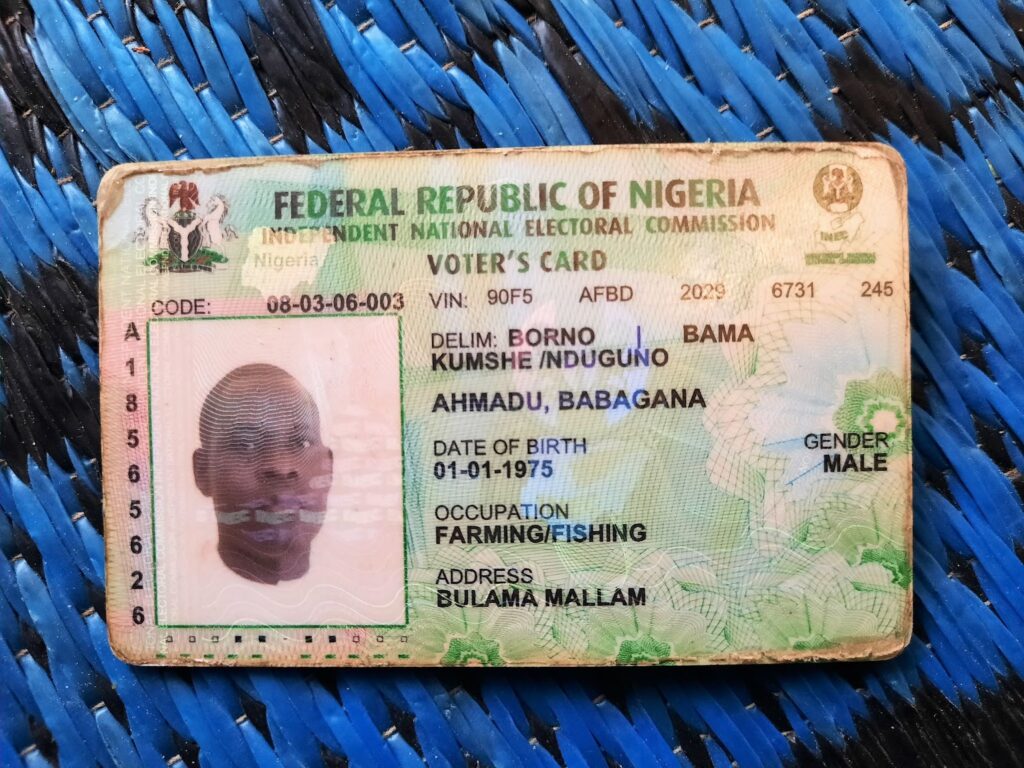

Then one midnight in 2014, an opportunity to escape presented itself. Over a hundred residents trickled out in batches, trying not to arouse suspicion as they headed east towards Cameroon. Among them were Amina, her husband Butu, her son Ba’ana Kura Amodu, her daughter-in-law Hajja Falta, her granddaughter Ya Khadija, alongside other family members. But, for some reason, not everyone who entered the bush on one side came out on the other.

Two of them were nowhere to be found.

After they left Kumshe, Ba’ana moved with six-year-old Ya Khadijah, whom he placed on a bicycle so she would not tire from the journey. His wife watched over the rest of the children separately. Somewhere along the line, as they made their way carefully through the shrubland, the family lost contact with Ba’ana and the girl.

“We searched but we couldn’t find him, so we left for Kulujia because it was getting late. The following morning, we asked those who came after us but they said they didn’t see him in the bush. That was how we lost him up to now,” narrates Amina.

The family stayed in Kulujia, a village in Cameroon, for two days before the authorities transferred them to the prison in Nigeria’s Bama area. After two days of screening, the military moved them to the Bama Hospital Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camp where they spent about two months.

“There was no food in the camp and people were falling ill and dying,” says Amina. “So they told us that anyone who has someone they know in Maiduguri can go there.”

As a fallout from the Boko Haram insurgency, which has been ongoing since 2009, Nigeria has had an alarming rate of people going missing. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) says it has documented over 24,000 people as having gone missing in the country, more than half of the figure across Africa. Over 90 per cent of the victims went missing due to the conflict in Northeast Nigeria and about 57 per cent are children.

The cases are oftentimes due to abductions by insurgent groups, arbitrary arrests by state actors, as well as the sudden, chaotic displacement of people from their home communities. The situation is worsened by the poor phone and internet penetration rates in Borno and surrounding states.

Amina has searched everywhere for her child and grandchild. There is no sign Ba’ana had an encounter with the military that led to his detention though it is common for people to go missing in this manner. Amnesty International estimates, for example, that at least 10,000 people have died in military custody since 2011, the majority of them arrested arbitrarily and detained without a trial.

During the brief time the family spent in Cameroon, Amina searched everywhere she could, including in Kolofata, Minimayo, and Salak. Despite her old age, she has been to several detention facilities in Borno, Nigeria, but no one, including former detainees, has confirmed seeing him. She has not been able to get any helpful information from members of the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) either. For eight years, she’s been in the dark about her son’s whereabouts.

“When the father was alive, he said he could spend any amount if he would get his son but they said they have not even seen his corpse,” she tells HumAngle.

A deadly domino effect

Ba’ana’s and Ya Khadija’s mysterious disappearance was not the end or maybe even the worst of the Amodus’ ordeal. The mist of trauma that settled after the incident snuffed out even more lives.

The first victim was Butu, 67, the family’s patriarch and a retired civil servant. He’d served as the chief cook at one of the secondary schools in Kumshe. Sometime in 2018, the depressed old man went in search of his son. Then a car hit him in the city’s New Prison district along the Maiduguri-Labe-Kukawa Road. He died immediately.

Ba’ana’s wife, Hajja, had been badly shaken too. She became hypertensive and eventually passed away last year. “Her life was miserable because of the loss of her husband. But we used to comfort her and cool her mind,” says the mother-in-law, who now takes care of the couple’s five surviving children.

The event has taken a toll on Amina herself. She is always thinking of Ba’ana. Again, losing her husband years later invited more grief than she could bear. She says she wept so much that she lost her eyesight. She could only see again after undergoing surgery. But that has not stopped the tears from flowing. Till now, the rims of her cloudy eyes visibly well up with water. Twice at least, a fly perches on the corner of her left eye, seeking built-up tears. An invisible weight creases her upper eyelids, just like her cheeks. And, when she is not speaking, she wears a default sad, distant look.

Amina is not a stranger to loss. Out of her 12 children, only five — two sons and three daughters — are evidently alive.

Her first-born, Moduye, became mentally unsound and the family had to leave him in Kumshe when they fled in 2014. They later learnt he was killed during an air force raid. Before him, five others had died, mostly of diseases during infancy.

Her other two sons, Umara and Shuaibu Amodu, were detained by the Nigerian Army alongside thousands of other people indiscriminately arrested during the period of mass displacements. While Umara was recently released from the Borno Maximum-Security Prison, Shuaibu was transferred to the Operation Safe Corridor Programme in Mallam Sidi, Gombe.

As for her daughters, two live with their husbands and the third resides in the Dalori displacement camp near the outskirts of Maiduguri.

‘He was a kind man’

Ba’ana, a tall man like his father, is the second child. He has the frame of a giant and two small tumours on his chest and neck, behind the left ear. He attended an Islamiyyah (Qur’anic learning centre) and then a regular school before dropping out after completing his junior secondary school. Because of his education, he speaks four languages, including English, Fulfude, Hausa, and Kanuri, and whenever he spoke, his voice was often loud. Ba’ana was a provisions trader and, during his free time, he would farm.

“He was very kind, charming, and helpful to the family,” Amina says. “He took care of all the family. He provided for our needs from his business.”

During conversations with his mother, he often asked her to pray for his trade’s success. If he made enough money, he promised, he would even sponsor her hajj to the holy city of Mecca. Hajj is the fifth of Islam’s major pillars and every capable Muslim is expected to perform the pilgrimage at least once in their lifetime.

Unlike her siblings, Ya Khadija emulated her mother’s skin tone, so she is darker. She has tribal marks too. She attended a Qur’anic school and was planning to cross into primary school before the family got displaced in 2014. “She was a fine and lovely girl who resembled her mother,” says Amina.

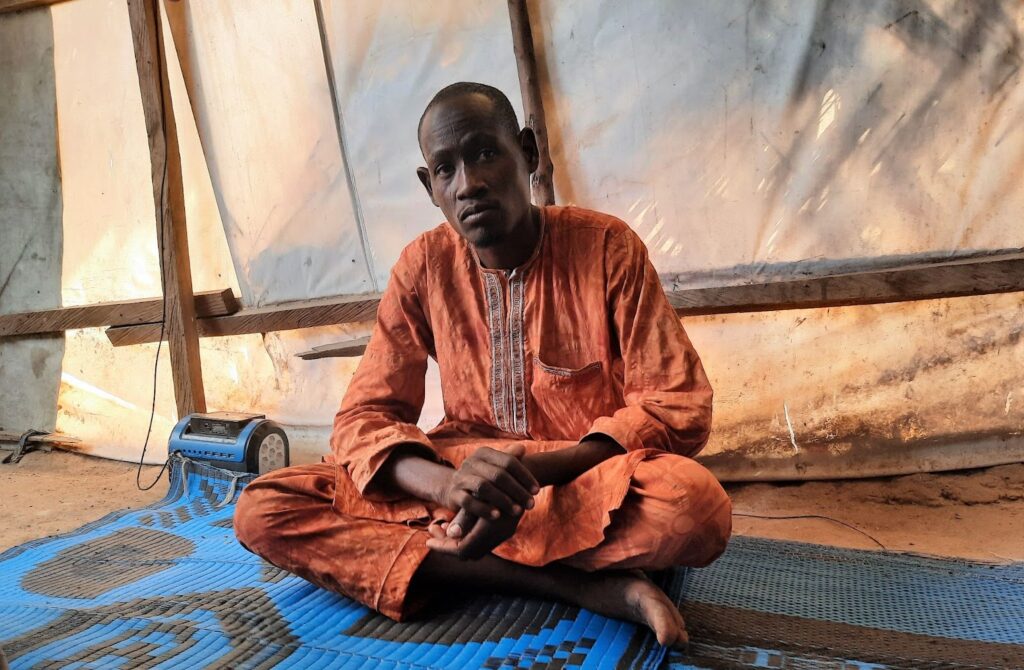

Umara Amodu, 40, remembers his brother, Ba’ana, fondly too.

“Whenever our father was not around, he assumed his role. He looked after us with care and loved all of us,” he says. Sometimes, when speaking about him, he in fact refers to Ba’ana as his father, the same way Amina occasionally calls him her husband.

Umara, who had been released from prison last November, had a different journey from the rest of the family after their displacement. He was separated from the others in Cameroon and escaped death by the whiskers several times.

“In Kulujia, the military beat us severely and, later in the night, they selected seven of us and took them away in a vehicle. After about 30 minutes, we heard some gunshots making us think they might have been shot. We neither asked about them nor did they tell us what happened but we never saw them again.”

He remembers there was another group of about 17 people beaten “almost to death” by soldiers using the gabkal, a corn planting tool with a sharp metal piercer.

“After that terrible incident, three of us came to Banki and, after screening us, they beat us again. When one CJTF officer told them I was a water vendor, they spared me but the other two confessed [to being Boko Haram members]. They were taken away after some time and we heard gunshots. Later the CJTF told us they were shot dead.”

The authorities then transferred Umara to Bama. There he met Hajja who mentioned Ba’ana’s odd disappearance.

A week later, he was blindfolded and taken to Giwa barracks, a notorious military detention facility in Maiduguri. He spent seven months here before his transfer to the Maximum-Security Prison in the same area.

Like other former detainees, Umara says Giwa barracks was a “very congested” place without adequate food and water during his time there. “Seven people died the day after our arrival,” he recalls, “and in a week 16 had died.” The conditions at the Borno Maximum-Security Prison were better. “There wasn’t enough food and water but they allowed us to sew caps and sell them; from that, we bought what we wanted.”

Umara was not able to communicate with his family until July 2020 — about six years after his initial arrest, and so his status had been uncertain just like Ba’ana’s. The prison officials, with a good-enough bribe, allowed them to send and receive letters. This was how he heard about his father’s accident and death. He would not know of his mother’s period of blindness until after his release.

Irreplaceable

Asked what she would say if she could send Ba’ana a message, Amina replies that she would tell him “we are all fine and waiting for him”. But the truth is she is not fine. Life has been tough without her husband and eldest son.

In the past, an international non-profit, Save the Children, supported her with a monthly donation of ₦5,000. When the aid stopped coming, she resorted to begging for money to feed herself and the grandkids. But with the state authorities later enforcing a ban on street begging, about a year ago she started selling small bundles of fried groundnut.

She often got between ₦600 and ₦800 daily from begging, sometimes in addition to foodstuff. In contrast, she only makes an average daily profit of ₦300 from groundnut sales. How does she cope? “We manage with what we have,” she replies. “Sometimes people would assist us with food and the children would sometimes go out and beg.”

If Ba’ana were around, not only would she be overjoyed, but she imagines she would also get tremendous relief. Surviving would not be such a burden. At least he would take care of the children, she says. And maybe someday revisit talks of getting her to Mecca.

This report was produced in partnership with the Open Society Initiative for West Africa (OSIWA) under the Missing Persons Register’s Population and Amplification Project.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter