A Man Who Survived Kidnapping And A Town Under Siege

Mustapha Shafi’i’s lucky escape from the clutches of his abductors is a sliver of light against the shadow of terrorism cast on one community in Zamfara, Nigeria.

It is almost midday in Yarkofoji and tens of people — men, women, and children, gather at the clinic. But it is not the urgent need for healthcare that keeps them from their work and schools this Wednesday. They are here instead to hear one man’s remarkable story. Though mostly solemn, the atmosphere is also celebratory. This could be because the man of the moment himself, 30-year-old Mustapha Shafi’i, is quick to smile despite his recent experience.

Mustapha, a rice and maize farmer, has just escaped from the stranglehold of kidnappers, who now notoriously terrorise the region without rest. He sits on a plastic mat at the clinic’s veranda, his legs stretched and his back resting against the butter-coloured wall. On the floor beside him are a small chunk of bread and a mug of tea, suggesting that he has not been around long enough to have a proper meal.

His ordeal started with a startling gunshot two midnights prior. The sound was followed by noisy activity at his front door. A group of terrorists, known locally as ‘bandits’, had raided the community and were leaving, but had decided to make one final stop.

Mustapha’s mud house, a stone’s throw away from the clinic, is in the less dense part of town, closer to the fringes. It is guarded by a cement fence joined to a narrow corridor that leads into a yard. The only noticeable obstacle to trespassers is the wooden door facing the street.

“After they knocked and there was no answer, they knocked down the door with their foot,” narrates Mustapha. “When they came in, I was already up. They said we should go. I pleaded with them but to no avail. I still resisted when we got to the entrance but they pushed me to keep moving.”

Mustapha was not the only victim that night. They had also kidnapped five children, aged between seven and 14 years: Ahmed, Hadiza, Saratu, Surajo, and Zuwaira. The young ones had been taken in place of their parents, who had been targeted but had managed to escape.

When the group got to the bank of the Sokoto River, about 2km north of the town’s outskirts, the abductors asked Mustapha if he had anything he could exchange for his freedom. Sincerely not, he replied.

Because of the children, the group had to find a shallower section of the river to cross. Some of the children held on to Mustapha for support.

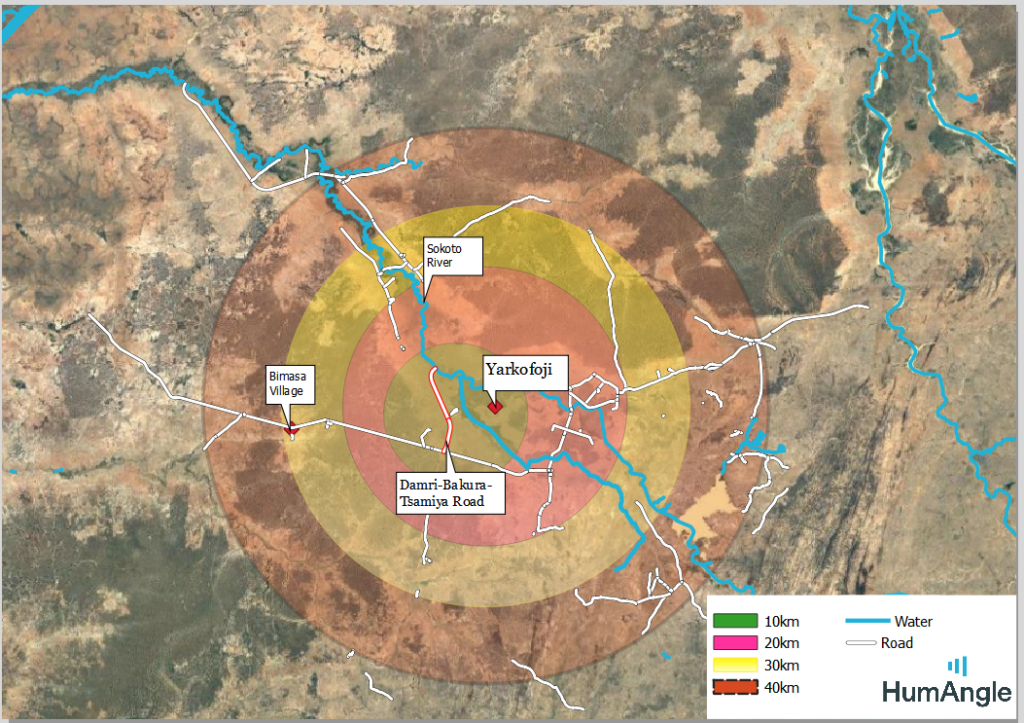

The terrorists, like their victims, were six. Two of them held guns; one wore a military combat uniform. They cleared a bush, made a temporary tent for the group to rest, and then prepared some food. They continued the journey at 5 a.m. the next morning, covering a much longer distance. In all, Mustapha thinks they must have walked for about 32km between Yarkofoji and Bimasa, a village in Sokoto at the border with Zamfara. That is like the length of the Third Mainland Bridge in Lagos — in three places. At a point, they crossed a prominent highway, he says, likely referring to the Damri-Bakura-Tsamiya Road that connects the two states.

“On our way, we saw a stream that cows have drunk from and defecated in. They fetched it and everyone drank from it. They also used it to cook rice and beans for us. If you had poultry, you would not feed them that water if you could help it.”

The abductors had foodstuff, pots, and other cooking items, which they kept in bags. Being without stoves, they dug in the ground and used firewood to prepare the meals.

After setting up another temporary camp, they tied Mustapha’s arms and legs. He protested and promised not to run, but his pleas were ignored. “They tied me up with a stick, like this,” Mustapha says, describing with the help of a thin, knotted rope.

“They tied me up and threw me around like an animal. And then they started beating me. One was using a bike chain; another was using a piece of firewood. They kept going at it. It was this hardship that made me realise I would not be able to stay with them. This was the second beating I got. They had beaten me the first night I was abducted as well,” he narrates as the grin he had worn since the start of the interview begins to fade.

He had previously been afraid of getting shot if he obeyed his instinct to run. But the beating motivated him to plot his escape. When his tormentors were done with him and laid down to sleep, he saw that he could pull up his legs. So, he did just that and started to slowly loosen the ropes. It was a few hours to midnight on Tuesday. Whenever he sensed movement, he would stop and try not to raise suspicion — especially from the terrorist closest to him who had a gun.

At a point, as he struggled, one of the terrorists woke up to perform ablution and observe the last two mandatory Muslim prayers. He then lit a cigarette and smoked. When he was done, he laid down and switched on a radio.

“He then got a call on the phone. He spoke with someone and the person was asking about the children. I then said they should please give me the phone so I could speak with the caller. I said they should please tell the people that we were looking for help. They replied that they would help me. They said my body would be sore from the beating they’d give me. They started beating me again. I thought maybe they wanted to kill me.”

After the latest round of beating, the abductors again laid down to rest and Mustapha continued to tug at his rope, hoping to untangle them. When he finally did, he removed the cloth tied to his head, ran into the bush, removed his shirt, tied it around his waist, and took off as fast as he could.

He got to Mararraban, an area on the border between Sokoto and Zamfara, and stopped to drink some water. Though he was exhausted and in pain, he hastened to continue, knowing that his abductors could be after him. He had already suffered to get this far, he thought, and his efforts could not go to waste.

“I ran and ran. But I found myself returning to the same spot. I was lost. I kept moving around the bush. I later realised I was not going to get water because there wasn’t any where I was trying to reach. And there had been some water close to a hill we initially passed. So, I turned around and started running back, crying. I kept running and running until the morning broke. I could not even get the water. I kept on running… The suffering I endured on my way back was worse than the one I endured when we were going in.”

When his search for water proved futile, he headed in the direction of the main road where he was sure to find cars. He eventually found people who asked him to wait in a ‘government office’ while they flagged down a vehicle. They offered him sachets of water, which he remembers wringing to the last drop due to extreme dehydration. They finally found a car but the driver would not help, fearing Mustapha might be working with the terrorists. Instead, he gave him ₦100. Using that money, Mustapha boarded a commercial motorcycle that returned him to the familiar faces in Yarkofoji as well as his wife and four children.

“I was walking in the bush from around 10 p.m. till the morning. And I swear I was not even wearing any shoes,” he says, his innocent smile finally re-emerging as the townspeople, listening all along with rapt attention, volunteer prayers and comforting words.

Mustapha’s wife, Asma’u, 25, says she was thankful to God when her husband returned home and believes they were “destined to reunite.”

“Yesterday people came to offer their condolences and today they came to rejoice with us,” chips in the survivor’s father. “And then today I was just sitting in his house. It was just me and my siblings. Lo and behold, we just saw him arriving on a bike.”

The terrorists often go after well-to-do members of the community or those with valuables they can part with. Asma’u remembers that those who abducted her husband asked who the house belonged to and whether Mustapha had any phone. “One of them exclaimed that ‘wow, this man even has a bicycle,’” she says. At a different time, the inhabitants of one house were attacked because a car had been parked outside.

The recent wave of terrorism in Zamfara dates as far back as 2011 and has since led to the killing and abduction of thousands of people. There were nearly 125,000 Internally Displaced People (IDPs) in the state as of February, according to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), many of them living in harsh conditions.

A gang of prayerful terrorists

Mustapha’s story shares parallels with those of other victims of kidnapping in the region. They describe the abductors as mostly Fulani. They are tied up, blindfolded, and fiercely beaten. There are also moments where the terrorists share personal information about themselves or discuss issues outside of ransom negotiation. Mustapha’s abductors, according to him, presented themselves like some serial criminals with a moral compass — “just waiting for the right time to stop while praying for Allah’s forgiveness.”

The audience, hearing this, erupts in laughter.

“They even put on wa’azi (religious sermons) for us to listen to. I swear that’s what they told us: to open our ears and listen to the preaching that was playing,” Mustapha continues.

“You’ll hear one of them recite a verse from the Qur’an and translate it. It’s not like they’re not knowledgeable because, if one of them speaks to you, you’ll be surprised at how they have this knowledge and are still doing this thing. I swear. But they honestly did not touch the children. They did not do anything to them, except the stress of walking long distances… It was me they kept beating.”

Recalling that they had threatened to beat him every morning and evening, he knew not to be fooled by the terrorists’ religious show. Earlier, when he told one of the kidnapped girls of his plan to escape, she questioned why he would leave them with the abductors.

“Well, you’re not protecting me from the beatings and they’re also not beating you,” he had retorted. “The pain was too much for me.”

A grief-stricken father

Umar Liman, a man in his late sixties, was lucky to have slipped away from the terrorists the night of June 7. But the invaders simply went with two of his daughters — Saratu and Zuwaira — instead.

He had heard people scaling the fence into his compound and had gone out with a torch to confirm what was happening. The light shone on three men, who asked in a hushed voice for ‘a small amount of money’. Umar then urged them to give him and his house a good look and determine if he was rich enough to spare some money. No problem, the intruders replied, before asking if he had a phone.

“At first, I said to them I didn’t have a phone. So, they told me to get my shirt. It occurred to me that they were most likely going to take me with them, so I picked up the little phone I had and gave it to them. One of them said, ‘Great, we’re really happy with that.’ But they insisted I put my shirt on.”

Umar complied but took permission to return to his room for his cap. He took off instead, climbing over the fence. “This fence right there,” he says, pointing behind him to a medium-height mud wall.

One of the attackers, who saw him escaping, rushed out of the house and flashed his torch towards where Umar had just landed.

“He shouted out saying, ‘Baba! Does baba run?’ And I replied saying, ‘Well, I do,’” he chuckles briefly. “He then went back inside to his people. I took off on this main road and kept moving. I found an uncompleted building and went in to spend the night.”

When he returned home in the morning, Umar met a crowd of people who had come to offer their sympathy and discovered Saratu and Zuwaira had been abducted. “I pray to God to assist me in the return of my children to my hands. That is all that I wish for,” he tells us.

A community under siege

Yarkofoji is in the northwestern part of Zamfara. It is a heavily agrarian community, with its vegetation sustained by the Sokoto River and the Bakolori irrigation project. It boasts of at least two primary schools, one government day secondary school, and has a population said to be over 320,000.

There is a sleepy police outpost by the town’s entrance, adjacent to the schools, but one look at the structure confirms why the community could have so easily been attacked. There are holes in the ceilings, apparently caused by termites, and holes in the windows, both the glass sheets on one side of the duplex and the aluminium sheets used on the other. Every part of the structure screams decay and underfunding, and the interior is even less cheerful. Wearing mufti and with no arms in sight, two men lounge on a mat outside the station. Security personnel at the post are not more than three. Some say there’s, in fact, only one real police personnel while others are volunteers.

“This is their fifth time attacking here,” says resident Atiku Abubakar, referring to the June 7 incident. “And, during all these attacks, there isn’t one where they faced strong resistance from anyone. They come here, do whatever they want, and leave.”

During one attack on May 22, the terrorists killed four people, shot four others who had to be hospitalised, and then rustled an estimated 300 cows and 500 sheep. The attacks here are said to have started around 2018 but have become especially worse this year.

“And what they’re saying is that they are just starting,” Atiku says with concern.

None of these attacks was reported by major newspapers. Atiku says even BBC Hausa and Zamfara’s Radio Service, which cover events closer to home, have not dedicated a line to the development.

Months later, however, two attacks made news: that of Aug. 12 where 11 residents were kidnapped and a second one on Aug. 15 during which eight people were killed and 17 others kidnapped. The graves of some of the victims from that month were shown to students of the Zamfara College of Agriculture and Animal Sciences, abducted a few days later, to instil fear in them.

“Things have spoiled. Because of the situation we are in, very few people get to sleep here. Everyone is thinking this could happen to them next,” says Atiku.

Pushed to the wall

People are afraid to defend themselves too. One, the terrorists could retaliate and kill even more people. You could also get reported to the authorities for illegal vigilante activity or treated as the original criminal.

“But the bandits, the real perpetrators, don’t get chased and caught,” laments Alhaji Jafaru, 40.

“You’ll take action by yourself and retaliate, only to get arrested. How can your attackers have weapons and you don’t? How can these bandits have weapons and the government does not?”

After reports of abuse and extrajudicial killing, authorities in Zamfara had in 2016 banned ‘Yan Sakai, a term that loosely describes self-help vigilante groups set up by various communities. At the same time, the state government has until very recently pursued a policy that favoured dialogue with terror gangs. Some of the groups reacted by shifting their violent campaigns to neighbouring states while engaging in talks with local authorities, but the attacks in Zamfara have never ceased.

Yarkofoji has largely complied with the ban on vigilante activities. The people say there’s even a sexist local song that famously mocks men who take up arms without the government’s go-ahead, describing them as inferior to women. But they add that the government’s kid-glove treatment has made them easy prey to terror attacks.

The townsmen no longer trust the traditional leaders, security agencies, and political authorities to have their best interests. They say during Local Government elections just months ago, tons of security personnel swarmed communities in the area; but when attacks take place, it takes soldiers hours to arrive.

“I swear, at a point, it seemed like if you were travelling on foot, you’d get here quicker than their cars,” teases Jafaru, his frown unrelaxed.

“The uniformed personnel are useless. It is until the deed has been done before they decide to show up and say they want to do something. Yesterday, after the children were captured, a certain DPO came and was asking why he was not woken up. But you will inform him and he won’t show up until it is over.”

Asides robbing them of their livestock, another way rising insecurity in the region is worsening poverty and food insecurity is the seizure of farmlands. Residents of Yarkofoji complain that the terrorists have started planting on their farms, located about 1km from the outskirts. They don’t live that far off, says Jafaru.

Helpless, the people make do with what is left of their resources as they anxiously expect more attacks. Many, however, insist they are ready to fight back once permission is granted.

“We have reached breaking point,” says Abdullahi Ibrahim, a young man who still has a bullet wound above his right ankle from one of the attacks.

“What we want from the government is they should give us the right to protect ourselves. And if they don’t, after today, that is it. Whoever decides to stand up, stands up; and whoever gets killed, gets killed. Whoever wants to stay home and lay low, should stay home and lay low. And whoever feels like they can stand up and protect themselves and their family should get up.”

____________

Like its police outpost, Yarkofoji itself is a sleepy community. It appears there have been more reports about people named after the town, like Zamfara’s commissioner for agriculture and natural resources, than the town itself. And wherever it was mentioned, the reports always had to do with its agricultural potential. All that has changed now.

The people tell HumAngle they want nothing more than to return to their undisturbed life.

“We don’t even want anything from the government,” says Atiku. “We are fine just doing our farming. Whatever we get, we make good use of it. We don’t want anything else. Because if you don’t have peace, whatever is done for you will not mean anything.”

Abubakar Yahya, a young man standing behind Atiku, looks eager to speak but hesitates for several minutes.

“Tell the world,” he finally cuts in. “Tell the world, we have been pushed to the wall.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter