545 Days (3): The Last Day?

The story of how Jummai Inuwa led five other women from ISWAP captivity concludes. She has spent 18 months in a camp on Lake Chad, and has been at the point of death many times. But their most dangerous moment is still ahead. Will they all make it out alive? Part one and two can be read here.

Jummai had spent over a year in captivity, she had been carefully observing the ways of the camp, trying hard not to make a wrong step and anger her captors or give them reason to harm her.

She had been informed that ransom demands had been sent to her family, but no news had come back to her after that.

Then the leader of the camp was changed without warning, and a new man came in. Jummai decided to push the issue a little and find out if there had been any progress.

The answer she received chilled her blood.

“I asked him about the stage of my ransom negotiation, and he said, ‘let’s see if your people would comply, and if they don’t, then we know what to do with you.’”

Jummai had seen how the slightest delay or hint of a hiccup to the negotiation process could lead to the killing of the captive. “They don’t bullshit the ransom,” she told HumAngle.

“That was what accelerated my plans to escape,” she said.

She had a plan. It had taken a year to develop. She reviewed and re-reviewed her ideas over and over again as she gained more information about her situation. She was beginning to feel good about it.

Optimism

“I was very optimistic that I would escape unhurt, and I told the other ladies that were later brought to join us in the cell to be ready, but I don’t know when.”

She did not tell them yet what the precise plan was.

“I gathered all that I needed to know about our location and the terrains of Lake Chad and then backed it up with God.”

Jummai assessed that the best moment for the escape was at the time of commotion in the camp. If they came under attack, the camp might descend into chaos enough for their escape to go unnoticed.

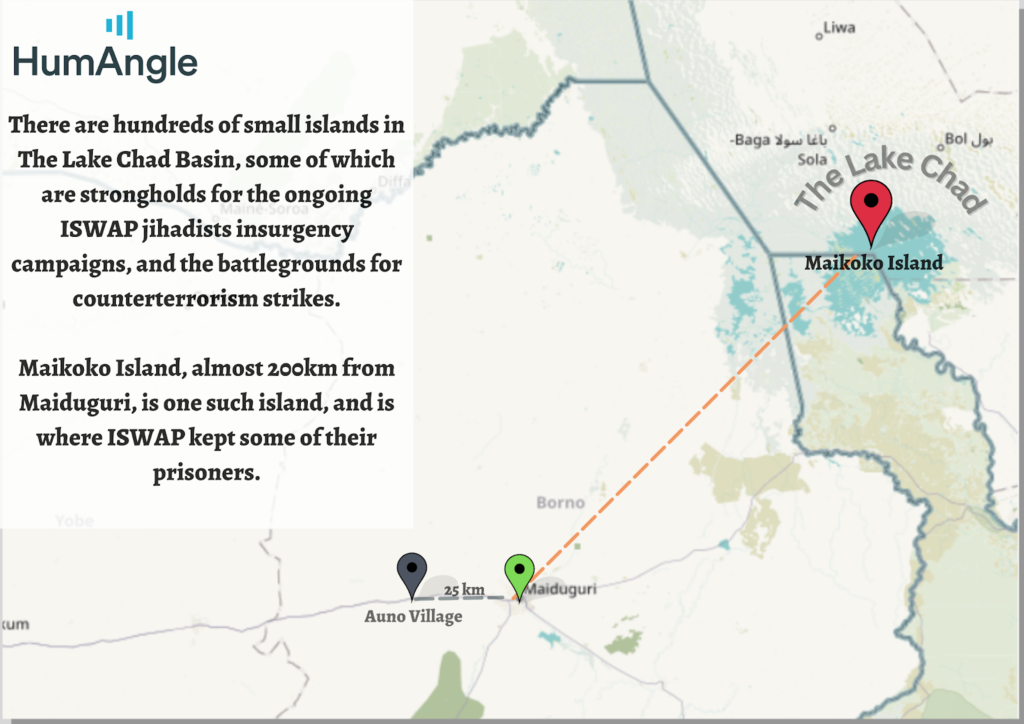

The camp was under the control of Islamic State West Africa Province. It had been attacked several times by fighters loyal to Abubakar Shekau, the former leader of the group known as Boko Haram, who had been killed by ISWAP a year previously. When the fighting had gotten closest, pandemonium had broken out with people running everywhere. Women and children were directed to a muster point away from the camp where they could be out of harm’s way or led away if it became necessary.

They had been moved once already, in the aftermath of an attack where Boko Haram fighters had come close enough to shoot it out. The women were taken from the prisoner camp where Jummai had been inducted into ISWAP captivity, to a village. The people who lived here were not prisoners, but loyal to ISWAP and its leaders.

She and other captives convinced the ISWAP commander that they would now be loyal, as the villagers were. They could be trusted. They were given some more latitude, to walk around -within limits- and even visit people who lived near the village.

“Yes, things were not as strict as they used to be,” Jummai said. “They allowed us to earn some little money for survival after we had assured them we won’t run again. So sometimes, after going to fetch firewood or water, we would sneak to the house of a woman who is a local trader and farmer, there we would help her to work on her farm like picking okra, pepper, etc., and she would pay some cash.”

There she learned they must be near the Nigerian shore of Lake Chad, people paid for things using Naira.

“I deployed all strategies of getting information daily through listening to their conversations in their local Kanuri language. I got a fair understanding of the language during my work in remote villages as an NGO worker. I also studied their body language to know if there was any problem or an attack that would be taking place.”

Eventually, the opportunity she had been waiting for presented itself.

D-Day

On 17 April 2022, the Nigerian military jets and helicopters had been bombarding the village where they were being held for four days.

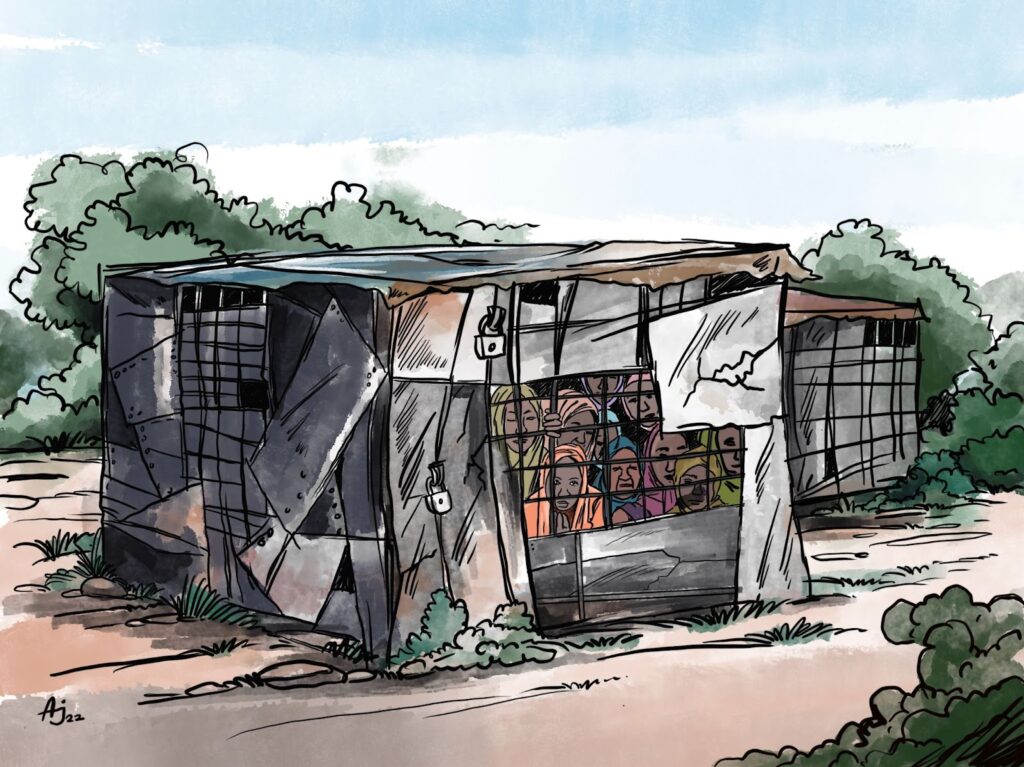

“So, I summoned the other women in our Sijjin (prison cell in Arabic) and informed them that the time has come for us to make our move.”

Two of the other women who were imprisoned with Jummai, and confirmed many of the details of her story, said they were in bad physical shape, but they knew they had to go with Jummai.

Martha, who had worked for an international NGO, had been in captivity for five months. “At one point I was like a walking corpse,” she said. “Death no longer scared me because I never believed I would survive or come back alive again. I have seen and felt death with my hands. I was just waiting for the day my turn would come.”

Susan had been a seamstress in Adamawa, before ISWAP came and burned her village down a year before. She had been in their captivity ever since.

“Jummai has been our source of inspiration and courage because she is the most senior among us. We had been nursing the plan to escape only that we had to wait for the best time.”

“So, we all agreed with her. We were all scared, but we had to brave up.”

Jummai had ascertained from her conversations with the wives of the fighters that the military was coming, they would soon be within shooting range of the camp.

If the ISWAP fighters lost the battle, the women understood they could not simply remain there and wait for the military to arrive, sitting in the holes they had dug to protect themselves from bombardment. They called these holes ‘bunkers’, but they also knew they could as easily be their graves.

“We also factored in the dangers of running into the Nigerian army troops who would mistake us as enemies,” said Jummai.

Martha said: “A woman, one of the wives of the Boko Haram, warned against staying inside the bunker. She said we had to run with them to another place because the infidels would come and kill everyone. We said okay.”

The ISWAP fighters gathered together and left to confront the approaching military forces.

“All the men in our locations were running out, and we could hear them speaking with their walkie-talkie devices,” Jummai said. “They left their wives and the kids, and some elderly men behind. The women later informed us that they were told to leave the house to avoid fire incidents, So they urged us to follow them. I told our team we were leaving, and they all agreed.”

Martha said “So, when others were running towards the so-called safe location, we went to the opposite side.” She was with a woman called Mama Khadija, who suddenly remembered she had to bring something from her cell and returned for it, much to Martha’s frustration. “When we observed that no one was paying attention to us, we sneaked and ran towards the lake water.”

The gunfire had started as they ran, Jummai said; “We set out amidst the shooting.”

“The shootings were intense,” said Susan. “The women moved to where they were told to go, but we did not follow them. We diverted.”

Sounds of War

Martha recalls reaching the water’s edge. She was afraid because she had never learned to swim. Few of the six women who fled knew how, except Mariya, who was from a Marghi fishing village on the other side of the lake. She could swim, they depended on her to navigate through the water.

“That was my first time being in water that is even beyond my knees. And this was neck deep. Mariya was leading in the water like a professional fisher and she knew the path through the water, telling us where and where to avoid.”

They waded in the water for hours, crawling through the weed and the rushes. When helicopters passed over their heads they ducked under the water.

Jummai had spent the days previously coaching the women about the sounds of war. She had grown up near a military camp and was familiar with the sounds of jets, how to identify where they are coming from before the screaming noise is above you and gone in a flash; and about the difference between a jet and a helicopter, and how the helicopter is even more deadly.

She had learned from the wives of the fighters that the military also have drones that they use to target firing and mortars, and how they must be avoided.

Eventually the sound of shooting subsided. The reeds and grasses thinned out and the water was not so deep.

But when we got out there was someone missing.

Martha says: “We were shocked to find out that Mama Khadija was not with us. She was nowhere to be found behind us. It was a moment of confusion for us. She was the one far behind us because we held onto each other’s clothing in line as we moved behind Mariya and Jummai.

“She had some difficulties moving quickly. We didn’t know at what point she was disconnected from us. We waited for about an hour and there was no sight of her. So, we concluded that maybe she was drowned in the water, or the Boko Haram guys must have caught up with her.”

Lost

They pressed on, but the water had been replaced by thick mud which slowed them down to a snail’s pace. They were making heavy going of it, and only reached the edge of the swamp by dusk on the first day.

“We headed for the bushes without any compass direction for the location of Nigeria, Chad or Cameroon,” said Martha, “we were lost in the middle of nowhere. But we kept on moving away from where we were coming from.”

After the sun had set and the darkness descended, they encountered a Fulani man moving through the bush. He was as startled to see them as they were of him, and both were wary. They had heard of other escapees being handed back to their captors by passing herders.

“We noticed him because the moon was bright and from his accent, we knew he was a Fulani man. We begged him to show us the direction to the Nigerian side of the jungle but he declined because he was scared,” Martha recalls.

He thought that they were wives of Boko Haram.

“He said if your men find out they would not spare me because even he is running for his dear life.” They asked him where they could get to a village they had heard would link them to Monguno, but the man refused to help them. They continued moving.

Hours later, deeper into the night, they heard cows mooing. They moved toward the sound and came across the herd.

“You again?!” It was the Fulani man they had met before. This time he felt comfortable enough to offer them a place to rest, indicating if they needed they should use one of his mosquito nets.

The women wondered whether they should come clean, tell him they were not Boko Haram wives, but captives on the run.

Military Base

Martha said they decided to tell him they were abductees escaping after years in captivity: “The man was honestly shocked to hear our story. So, he asked what we wanted from him. And we said just show us the way out.”

Reluctantly, still perhaps suspecting they had not told him the whole truth, he pointed them the way to Arege, where the military had a base.

“He said, but you must be careful because there are soldiers on the way and if they see you they will kill you all,” Martha remembered.

“He told us that should we get to any crossroad, they should follow the path of the moon. He was also very resourceful to say that the distance between us and the military location at Arege, a male traveller on foot would arrive by dawn. So, he said we had to walk faster.”

Eventually, 36 hours after they set out from the camp, they arrived near the village. It was smashed and burned, they could see none of the houses had any roof. The rescue would not be a simple matter, they knew.

“We did not go straight to them,” said Jummai. “We had to carefully manoeuvre our way up to them so that they wouldn’t spot us, and think us enemies.

“We walked all day, and we became so tired and famished that we had to pass the night somewhere and that was for about an hour and some minutes before we were forced to wake up by the sounds of some heavy vehicles.”

They could not be sure they were from the military, and they waited until dawn. At first light, they began to fear the military had withdrawn, and the men that were so near them could be Boko Haram fighters. After all, when some of the women had been seized, they had been put into vehicles just like those ones.

Jummai said “At one point, some of my girls started giving up because we were no longer sure of what would happen next. And the fear of the consequences of being caught by the terrorists worried us. We knew it would be summary death – not by execution; but by brutal slaughtering and beheading. I had to encourage them not to give up.”

They headed for the cover of some nearby trees to rethink what to do next. They saw some men standing on the top of a building that had been burned.

For Martha, this was not a moment of relief: “We had left the forested areas and were now in the desert where everywhere is open, with little places to hide.”

Then they heard something that settled their minds.

Singing

“Suddenly we heard some of the men singing – and I told my girls that this is different because terrorists don’t sing. They don’t like it,” said Jummai.

They heard the men speaking pidgin, which encouraged them more. “So, at that point, we became transfixed. Who would go first?”

The greatest risk was that the soldiers would think they were female suicide bombers and lkill them before they had a chance to detonate their belts.

They decided not to go straight to them, they moved sideways around them.

“Some of them immediately spotted us and I saw them turning the barrel of their gun track towards us.”

Susan was terrified “The soldiers had begun to fire into the air, and all that we prayed for was for them not to mistake us for suicide bombers. It was God’s intervention because anything could have happened.”

Jummai told them to do what she did. She threw herself to the ground and held up her hands. They all started shouting “we are victims, we are victims, help us, help us, we are victims” in English.

“God intervened and they heard us and they stopped shooting,” said Jummai, “but before we could raise our heads, many big military vehicles had surrounded us.”

Questions were barked at them: Who are you; where are you coming from; how do you know we are here; how long have you been here?

“I was the one doing most of the answering,” said Jummai. “I heard their leader speaking in walkie-talkie to his commander that “they are women sir, but they can speak English, they said they are victims.”

Nevertheless, they were searched and blindfolded, before being taken away.

A Stranger at Home

The ordeal of captivity was over. But by no means was that the end of all hardships.

Though a free woman, Jummai, is still battling with untreated trauma. She says she is not a happy woman, considering how society treats her today.

“It was not easy. But despite being free today, sometimes I ask myself if it was the best decision that I took to escape,” she said, tears flowing.

“At times the feeling for me is here I am; out of captivity but I still feel like I am still in captivity. This is how I feel about the situation I found myself in right now.

“While I was in captivity, nobody cared about us – they don’t care if I was alive or not.” At one stage she fainted, having not eaten a thing for days. “When I was revived, the other survivors were saying that when they informed our abductors, they only asked if I was dead or alive. They did not care. If I were dead, they would only bury and that would be all. They don’t care.” She said she willed herself never to fall sick again.

But in the world outside the camp, she feels that there is also a lack of care. “When I finally made it out…it is not all people that would understand what trauma is. People don’t care.”

“When I was in captivity I had sisters in captivity who showed love and we cared for each other. We laughed together and cried together; we prayed together and encouraged one another. But now that I am out, I am left alone to deal with my problems. I am not saying life there in the bush is better. No. Never. But the way people treat you, without caring for your trauma, makes me feel as if it was my fault that I was abducted.

“Everything has changed since my return, making me wonder if this was the country I left about two years ago. I knew and later learnt that people prayed for my freedom. But now that I am out, it was like they only cared for me when I was there in the jungle. Now that I am out and need all the support – psychologically and otherwise – it wasn’t there anymore. The only thing that gave me joy was that I did not only save myself but I saved others by helping them to escape. Not only with those that we escaped together, but I also saved many others before and even after my escape.

Reuniting with her family brought her intense joy. But it hasn’t been a straight road. “I was happy. But everything has changed. They no longer see me as the person they used to know. Some will come and continue staring at me without saying anything because they thought I have gone wild.”

There are more malevolent reactions too. “Sometimes I overhear people saying in a hushed voice that ‘you people should be very careful about her oh.’ Sometimes I smile. I continued to battle by showing that I am normal even if I am sick and tired. I had to prove to them that I am okay and not mentally disturbed. Sometimes they ask questions that are funny and yet …hurtful.”

Read the other parts below:

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter