Why There’s No Federal Character In Nigeria’s Poverty Distribution

When the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) released an executive summary of the 2019 Poverty and Inequality Report in Nigeria nearly two weeks ago, it was obvious the problems identified are more prominent in certain regions of the country. This, experts have suggested, is as a result of differences in literacy and fertility rates, access to healthcare, among other factors.

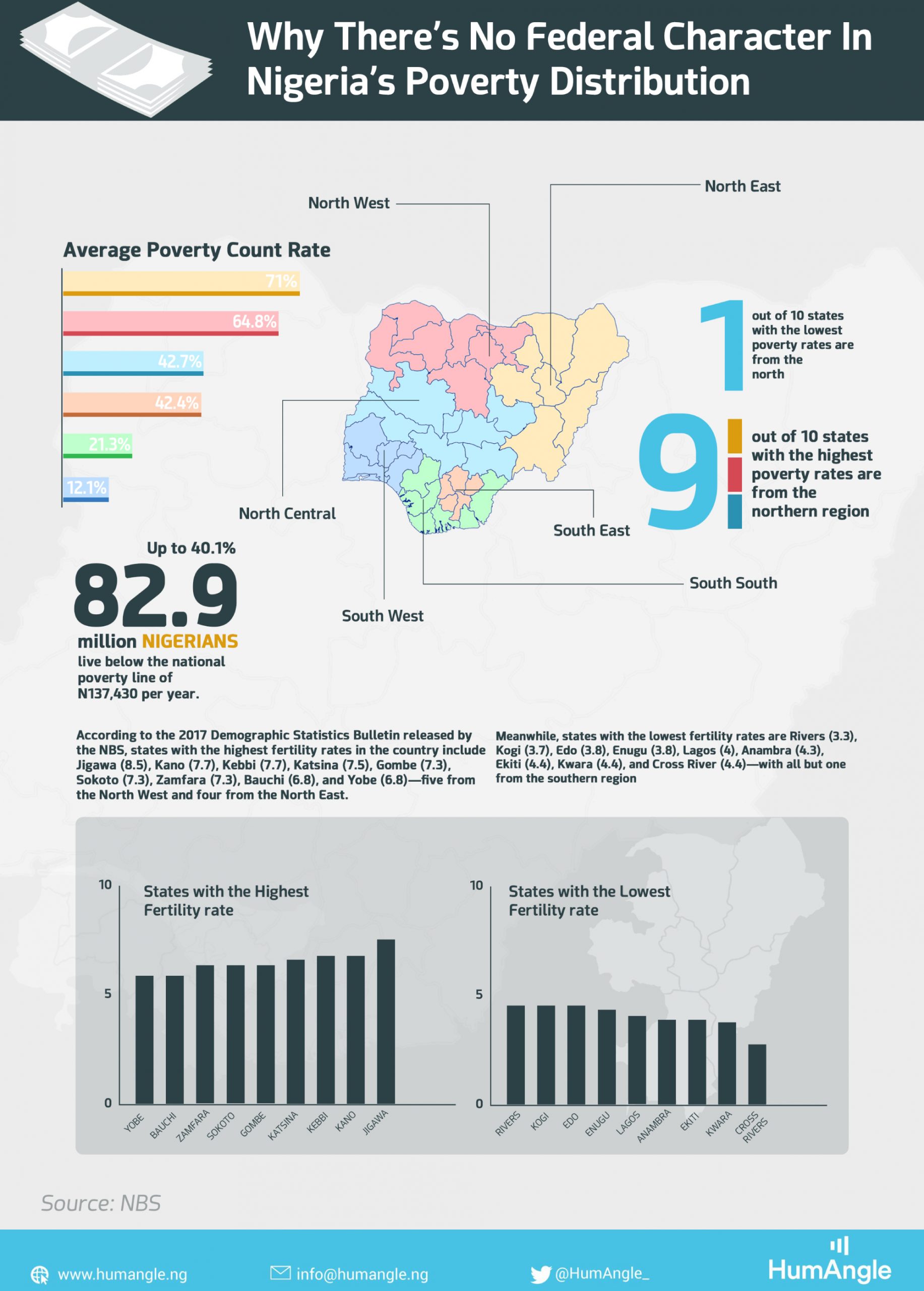

According to the NBS report, up to 40.1 per cent of Nigerians (82.9 million) live below the national poverty line of N137,430 per year. The threshold is by its estimation how much a person needs to have a “basic level of welfare” after taking care of food and non-food expenses such as shelter, clothing, medicine, and education.

It further revealed that there were common variations in how people were according to different variables, including gender, location, literacy, and occupation.

For example, people living in urban areas are less likely to be poor compared to those in rural communities. People with higher levels of education are less likely to be poor compared to those with those who are not as educated. And then, Nigerians who live in the northern region suffer from significantly higher poverty rates compared to those who live in southern states, the report said.

Analysis by HumAngle shows that with an average poverty rate of 71.9 per cent, the Northeast is by far the most impoverished geopolitical zone in the country. The statistics do not include figures from Borno State, the hotbed of Boko Haram insurgency, because, according to NBS, only “safe to visit” households were interviewed.

The zone with the second-highest poverty rate is the Northwest (64.8 per cent), followed by the North Central (42.7 per cent).

The Southeast only fares slightly better than the North Central with a poverty rate of 42.4 per cent. It is followed by the South-South, which has a much smaller rate of 21.3 per cent and the Southwest (12.1 per cent).

The divide becomes more obvious when we consider that nine out of 10 states with the highest poverty rates are from the northern region—with the only exception being Ebonyi—and they constitute 88 per cent of all states that fall above the national average poverty rate.

On the other hand, only one out of 10 states with the lowest poverty rates is from the north: five are from the Southwest, three from the South-South, one from the Southeast, and one from the North Central.

Also, only 21 per cent of the states that fall below the national average are from the region, all four of them from the North Central.

Professor of Economics and Director of the Centre for Sustainable Development at the University of Ibadan, Olarenwaju Olaniyan, said, for him, some of the takeaways from the report included that poverty is both a rural phenomenon and a “northern geopolitical zone phenomenon”.

“If you divide Nigeria into two, you will find out that most of the states with great poverty rates are up north and if you come down you will find out that apart from Kwara and Kogi, the lowest 16 states, you will find out that all of them are in the south,” he observed.

This unequal distribution of wealth, he explained, reflected the shortcomings in the manner of governance in the northern region and lack of adequate attention paid to human capital development through education, health and employment.

“The other reason is also that we have high fertility rates in the north,” he continued.

“And the number of children you have determines the dependency rate in a particular environment and that can also translate into what we call the support ratio, meaning who are the people who can work to give support to others.

“So, if nine people out of 10 are poor, you’ll find out that only one person is working to support 10 people. And if you continue to have a higher number of children, then it makes it difficult for you to get out of poverty in a short while. The indicators are not so good in the states that are poor.”

According to the 2017 Demographic Statistics Bulletin released by NBS, states with the highest fertility rates in the country are Jigawa (8.5), Kano (7.7), Kebbi (7.7), Katsina (7.5), Gombe (7.3), Sokoto (7.3), Zamfara (7.3), Bauchi (6.8), and Yobe (6.8)—five from the North West and four from the North East.

Meanwhile, states with the lowest fertility rates are Rivers (3.3), Kogi (3.7), Edo (3.8), Enugu (3.8), Lagos (4), Anambra (4.3), Ekiti (4.4), Kwara (4.4), and Cross River (4.4)—with all but one from the southern region.

While speaking to journalists in February, Professor of Law and former chairman of the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), Chidi Odinkalu, talked about the disparity in fertility rates across the country.

“Average fertility per woman in the Northwest is just under 8.1. In the Northeast, it is about 7.9. In Lagos, average fertility per woman is now 4.09,” he noted.

“Now, what is the difference? In much of Lagos, many of those people will be one family of husband-wife and child. In much of these other places, average fertility per woman is not the same as average family size. So, when a man can marry four wives with average fertility of 7, that gives you 28 children.”

He added, “At that family size, you cannot just live-off your legitimate livelihood and at the same time sustain those children and send them to school.

“It seems to me that, at some level, the leadership of northern Nigeria has got to open up about population size. The Emir of Kano tried to do that and see what happened to him. It is a very delicate conversation but it has to be had. Why do I say so? Right now, that is Nigeria’s biggest national security crisis.”

Another factor that cannot be disregarded is the high level of insecurity in the north and how this has further impoverished the people. The Boko Haram insurgency that sprang up in the Northeast in 2009 has since led to the death of over 51,000 people and the displacement of 2.4 million others. The activities of terrorists in the region have worsened the food crisis and made access to healthcare and education difficult.

As Olaniyan noted, there was also a lack of adequate access to formal education.

According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), as much as 69 per cent of the 13.2 million out-of-school children in Nigeria are from the northern part of the country.

“Children need both [Islamic and formal education],” UNICEF’s Deputy Representative in Nigeria, Pernille Ironside, said in 2018.

“They also have a right to learn to read and write, mathematics and develop the knowledge and skills that will enable them to be contributing citizens of Nigeria.”

A senior official at the Central Bank of Nigeria, who asked not to be identified, said that the country needed to invest in infrastructure in healthcare, credit and education to end poverty.

“If all these things aren’t in place, you cannot expect people not to be poor. For example, in 2020 how much was spent on infrastructure?” the official asked.

“I mean the COVID-19 pandemic has shown we don’t even have a healthcare structure, something as basic as drinking water we don’t have. One per cent investment in America leads to 6,000 jobs, do we have such numbers in Nigeria?

“We cannot be struggling with electricity and not have good roads and think we can do better than what we are doing. This is a generational issue.”

The source added that state governments could lead the charge to end poverty rather than waiting for direction from the Federal Government.

“Apart from the national level, states can begin to do more. The Akwa Ibom State government opened up a factory to make medical supplies.

*We need leadership that will think outside of the box; we need to take these things seriously and do what we can,” the source said.

(Additional reporting by Itoro Udofia)

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter