Why Local Conflict-Reporting Lacks Depth And What Journalists Can Do Differently

Insecurity has, for many years, occupied a central position among an array of dire problems Nigerians face. For people in the northeast, it manifests mainly as the Boko Haram insurgency.

For those in other regions of the north and middle-belt, we have banditry, inter-communal conflicts, and clashes between herders and farming communities. In the south, kidnapping, cultism, and robbery remain major threats to lives and properties. In spite of this tragic backdrop, media institutions are not doing enough to properly capture these events.

The Premium Times Centre for Investigative Journalism (PTCIJ) recently studied the coverage patterns of conflict and humanitarian issues in Nigeria and found that about 90 per cent of media publications on these issues lacked depth. The study had covered contents released between January and March 2019 by 10 print-based, online, and broadcast news organisations.

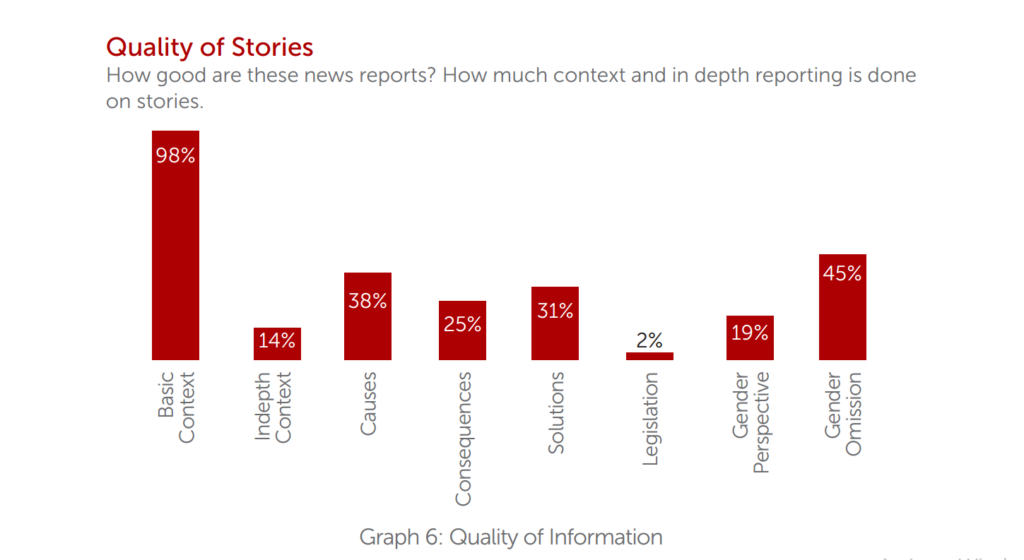

Following their analysis, researchers at PTCIJ concluded that up to 98 per cent of the reports related to conflict were basic. They only succeeded in providing a “mere recounting” of events while missing out on opportunities to provide context and fresh perspectives.

Additionally, only 38 per cent of the reports touched on the causes, 25 per cent highlighted the consequences, 19 per cent discussed the gender perspectives, and two per cent mentioned how relevant laws could shape the issues.

The centre said 31 per cent of the reports addressed the issues from a solution-perspective but quickly pointed out that the bulk of these were opinion articles.

It is not the first time shortcomings in how the local media reports conflict will be brought up. A 2018 study by researchers at Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium, charged Nigerian journalists with not emphasising the underlying structural causes of conflict and so allowing for ethnic and religious differences to be bandied as motivations for violence.

“This may have serious consequences for people’s perceptions concerning the possibility and feasibility of peaceful conflict resolution and coexistence,” the authors explained.

The prevalent superficial style of reporting could prevent the public from fully relating to or even thoroughly understanding security-related issues that affect them. And it is especially worrisome in a country with plenty of such issues.

Nigeria is ranked the third most terrorised and 17th least peaceful country in the world by the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) in its 2019 Global Terrorism Index and 2020 Global Peace Index respectively.

The Boko Haram insurgency alone has killed over 37,500 people since May 2011 and has led to the displacement of 2.5 million people in the northeast. Today, 10.6 million people in Adamawa, Borno, and Yobe need urgent humanitarian assistance while 4.3 million face an immediate crisis of food shortage.

The farmer-herder conflict has likewise displaced hundreds of thousands of Nigerians and led to the death of thousands of people — at least 1,300 in the first half of 2018 alone, estimated the International Crisis Group.

Because of a general lack of safety in many parts of the country, the government of the United Kingdom advises its citizens absolutely against travelling to four states in Nigeria and parts of six states. It adds in its travel advisory that only essential trips should be embarked upon to nine other states. The United States similarly lists 15 states across different regions that should be avoided due to, it says, terrorism, kidnapping, crime, and civil unrest.

And it is not only other countries, international non-governmental organisations, and statistical bodies that have sighed over the country’s poor state of security. As of 2019, Nigerians considered crime and insecurity the second-most-important problem affecting them after unemployment. It was even more important than healthcare, housing, corruption, and education, the respondents said, according to the National Bureau of Statistics.

This shows that by paying insufficient attention to this sector, the media is not only allowing violence to fester but is also doing itself a disservice by ignoring a set of issues dear to the heart of its audience.

Meanwhile, another indicator of the lack of essential contexts in most conflict-related stories is their format. PTCIJ observed that 79 per cent of the reports published and aired were news stories, 10 per cent were news in brief, four per cent were opinion articles, two per cent were photographs, another two per cent were editorials, one per cent were feature articles, and then interviews equally constituted one per cent of the contents.

“These formats [news and photographs] leave the least room for in-depth analysis and often don’t carry a lot of information,” the centre summarised. That feature stories, editorials, and interviews are incredibly few reflects a misplacement of priorities in many newsrooms.

There are various reasons for the current state of conflict-reporting in Nigeria. Murtala Abdullahi, a security analyst and researcher with the Conflict Studies and Analysis Project at The Global Initiative For Civil Stabilisation (GICS), highlighted some of the factors as the lack of specialisation, resources, and objectivity, as well as the fear of backlash from state agencies.

“Some journalists and media firms do not take the middle ground. They tend to report from the lens of politics, the security forces, or one of the main parties of the conflict. This affects the depth of reporting,” he remarked.

Abdullahi, who is also the founder of Goro Initiative, a platform that drives awareness and dialogue on climate, conflict and humanitarian issues, said this bias could explain why little is known about gangs operating in the Niger Delta or bandits in the Northwest and why reporting about the killings in Southern Kaduna is often lopsided. Objective reporting is necessary to make proper diagnoses and come up with lasting solutions, he argued.

“If you do not report properly, it means the solutions that will be implemented will also be problematic and we will end up creating more problems.”

Senior investigative journalist at Premium Times, Taiwo Hassan Adebayo, cautions that the quality of reports from newsrooms would ultimately determine whether they are helping to alleviate conflicts or are, in fact, exacerbating them. In order not to worsen an already dreadful situation, he advised journalists to favour field reporting over simply depending on official sources or second-hand accounts. Anything outside this would only promote single narratives, inflame passions, and further deepen the lines of conflict, he said.

“Without witnessed reporting that is not only on-the-ground but affords the public access to non-official yet true accounts and exposes abuses and failures, the media may inadvertently be investing in supporting injustice and abuses, covering truth, and further drawing out the conflicts,” Adebayo added.

What can be done differently?

Improving the quality of conflict-reporting, according to Abdullahi, first and foremost requires that we have journalists who specialise in the area or are even experts in specific kinds of conflict, such as the insurgency.

He further recommended that more resources are invested in this field of journalism, opportunities are available to improve the capacity of journalists, and the government should grant reporters freedom to carry out their duties.

“This is because, if they do their jobs, they are helping the government to solve a problem and are documenting atrocities for prosecution. This is super important. Journalists help to get justice for victims and highlight some of the causes of conflict and dynamics that keep conflicts going,” he concluded.

Beyond the structural support required from the government and media institutions for conflict reporters to thrive, however, Dr Theophilus Abbah believes journalists themselves have a lot to do in improving their craft. He advised them to, for example, avoid hate speech, avoid reporting verbatim quotes and sentimental statements from affected parties, provide backgrounds and historical contexts, and hear from the government on what it is doing to help and why, despite those measures, the conflict had yet to be resolved.

It is also important not to glorify those committing atrocities, the programme director at Daily Trust Foundation added. This can be done through the publication of statements, justifications, and upsetting images, which portray them as triumphant. He advised that journalists should rather make heroes of the conflicts, such as vigilantes and medical personnel, the focus of their reports while also humanising the deceased victims.

“We keep saying it is not just anybody who should enter into the field [for conflict-sensitive reporting],” he stressed. “The person reporting should have a measure of experience. He should know the context of the conflict. He should know people who can proffer solutions to that conflict. And the solution element must be in-built, even if it is just a sentence.”

Media executives to the rescue

In getting reporters to up their game, media executives and stakeholders have a huge role to play, observed Motunrayo Alaka, executive director of the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ). The findings in the report by PTCIJ align with the centre’s research over the years, also highlighting the need for more depth in reporting. And this is not a problem limited to issues surrounding conflict alone.

“We have found that particular fact consistent among issues we have monitored in the Nigerian media. I am not surprised,” Alaka said.

One of the major problems, she explained, is that media organisations overestimate the capacity of their reporters to cover specific issues that ordinarily require special training. This is because it is important journalists understand the socio-economic dynamics and societal nuances underlying examples of conflict. In the northeast, for instance, such issues would include poverty, lack of access to education, gender inequality, family planning, religious ideologies, and so on.

Asides active mentoring, to build the capacity of reporters, the WSCIJ boss suggested the involvement of experts such as political scientists and specialists on conflict issues, not just fellow journalists, during training events.

“A lot of newsrooms are waiting for training from WSCIJ, PTCIJ, Thomson Reuters Foundation, etc. but I am a strong advocate of in-house training,” she said.

“Many newsrooms have veterans but they only do their work and go home. The media houses need to begin to tap into and maximise the resources they have in-house to train their new sets of reporters. Find some day in the week to sit this person down with other members of the newsroom to do some experience sharing.”

And if a newsroom does not have an expert on a subject, she added, it should seek support from sister media houses. “The name of the game in this age is collaboration. And even though media houses are competitors in terms of the business aspect of their work, we are largely collaborators because our aim is one: having a better society where there is accountability and social justice,” she argued.

“In Nigeria, the resources are many. There are so many great minds, journalists of old, current journalists who can help us develop people in the media and we just have to leverage them and of course it doesn’t cost so much to do.”

Why we need more depth

Improving the quality of conflict reports is not just about good journalism. It has a direct impact on people, especially those whose lives have been upturned by violent events.

According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), since 2016, 3,559 people who were wrongly accused of being Boko Haram members or collaborators have been released from prisons and military detention centres in the northeast.

This victory can be traced to a 2016 report by Amnesty International, where it exposed inhumane conditions at Giwa Barracks and the trend of indiscriminate arrests adopted by the military.

The husband of Yakura Hajja Babagana, an internally displaced woman in Maiduguri, Borno State, is still in detention since they fled their hometown in 2016. Nevertheless, she recognises the usefulness of quality journalism in getting justice for underrepresented people. Before researchers from Amnesty International showed up, she said, not many journalists came to hear about their experiences. No reports were published by the few who did.

“It is good because before we started talking, nobody was released but this changed when we started speaking out,” she said. “Some of us have been able to get their husbands and people are able to get accurate information and the true story.”

Hundreds of women in the region, like Yakura, are still hoping to reunite with their husbands and sons. And they look to objective, patient conflict-reporters as sources of hope in making their aspirations a reality.

Support for this report was provided by the Premium Times Centre for Investigative Journalism with funding support from Free Press Unlimited.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter