Where Do You Run To?: A Tale Of Unequal Access To Aid For Adamawa’s IDPs

The decade-long insurgency that originated in Borno has spilled over to communities in neighbouring Adamawa, where many also fled their homes to reside in camps. While the poor living conditions of these people are glaring, there has not been equal access to aid and humanitarian support for them compared to their Borno counterparts. Why?

Musa Tela’s children were playing, his wife was turning corn flour to pap while he and his friends socialised beneath a tree when word came from their community’s chief. Everyone in the village and its surroundings was advised to flee.

“By 12pm sharp, we had left,” Musa recalls.

Tela was a farmer in the Gwoza area of Borno, northeastern Nigeria, when the Boko Haram insurgency started. He owned a house in Madagali, a community bordering his hometown, in neighbouring Adamawa, and so he and his family sought refuge there.

“But there were no lands for us to farm,” he says. On Aug. 1, 2014, Musa heard that some of his clansmen were in Yola, Adamawa’s capital, so he travelled there. He found farmland and started to prepare for crop cultivation.

After two weeks of visiting Yola, he journeyed back to Madagali where he thought he and his family would be shielded before it was safe to return home to Gwoza.

“By Friday, I was in Madagali and by Saturday morning, the boys attacked,” Musa Tela says. He had been displaced again.

Tela’s account is just one out of the millions of stories of people who have been, and are still being driven out of their villages and hometowns due to the decade-long insurgency across Nigeria’s northeast.

That moment’s decision of where to go when they initially fled set the course of their lives for the next decade. And because he fled across the state border into Adamawa that would set the conditions for the help he and his family would receive.

While the terror attacks that originated in Borno gradually spread over to Adamawa’s northern senatorial zone, victims in these communities have not had the same humanitarian attention as their counterparts even though they face the same plight.

The case in Adamawa

In Adamawa, the insurgency was most devastating in Madagali, Michika, Mubi (south and north), and Maiha. These are communities bordering Gwoza, Damboa, and Askira-Uba in neighbouring Borno that were worse hit by the insurgency, and they are also near the infamous Sambisa Forest hideout.

“Geography has played a major role in this crisis,” explains Chinyere Alimba, Associate Professor at the Centre for Peace and Security Studies in Yola, suggesting that the proximity of these communities enabled the rapid spread of terrorism.

Due to these attacks hundreds of thousands of locals have been displaced by the insurgency, causing camps to spring up across the state.

Muhammed Suleiman, Executive Secretary of the State Emergency Management Agency (AD-SEMA), tells HumAngle how the primary reason for setting up IDP camps in Adamawa was to shelter indigenes of neighbouring Borno who were fleeing from the war.

“It all started when there were [terror] attacks in southern parts of Borno,” he says in a phone interview. “And when there were attacks in communities of Madagali, we moved the camps from Madagali to Mubi, where we established two camps. That was in 2013.”

Towards the end of the year, more communities in Madagali came under the control of the Boko Haram terror group and the agency began to set up camps in the state capital.

“At the time, we had about 30 pockets of camps here and there with over 300,000 displaced persons.”

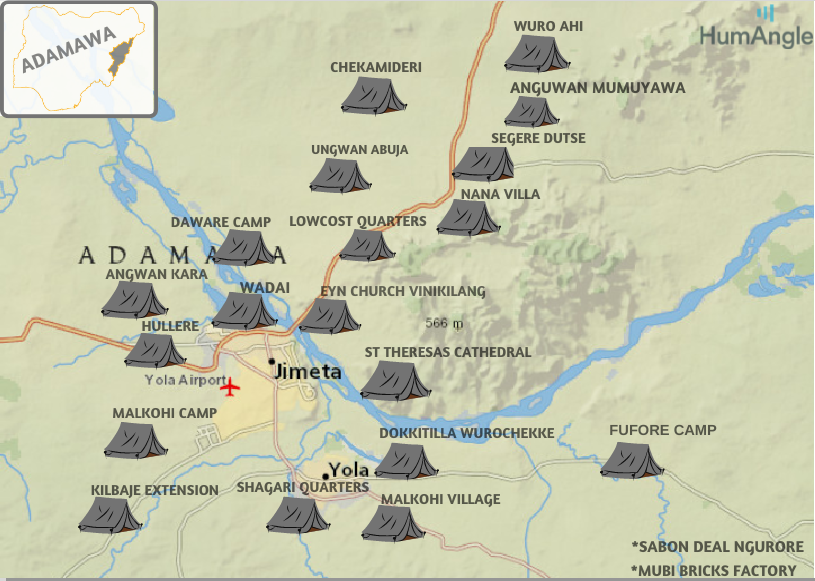

Currently, these settlements have shrunk to 21, with only four recognised by the state government receiving aid from AD-SEMA. However, even these provisions have not been regular.

Hamza Gakafa, a 56-year-old man who also fled from Gwoza to the Wuro-Ahi camp in Fufore, Adamawa, tells HumAngle how, when they newly arrived, food was provided on a daily basis. Other relief materials were shared frequently too. Even the shirt he currently has on, he says, was donated by the AD-SEMA.

There are similar accounts in Yola’s Malkohi camp as Hauwa Muhammed recounts how food was donated on a daily basis. AD-SEMA officials usually prepared meals in the camp’s central kitchen and shared them amongst IDPs.

The executive secretary, Suleiman, calls this approach ‘wet feeding’. Later, following complaints from the displaced people, the agency started distributing dry rations, grains, and condiments instead.

Now, displaced persons say food items and relief materials have been unavailable for months, or even years, save for donations from private individuals and local NGOs.

Safiratu, a displaced woman in the Wuro-Ahi camp, thinks the agency only supports camps within the state capital due to their proximity, neglecting other camps.

“When we came here [the camp], they gave us food items, clothes, soap, everything we needed every month, but it has been four years now since we saw even a wrap of salt from them,” she says.

AD-SEMA says this is not true. “There is no way we would share relief materials in other camps and single them out. NEMA provides staple food and SEMA is in charge of distributing,” Suleiman explains.

Not the same humanitarian attention

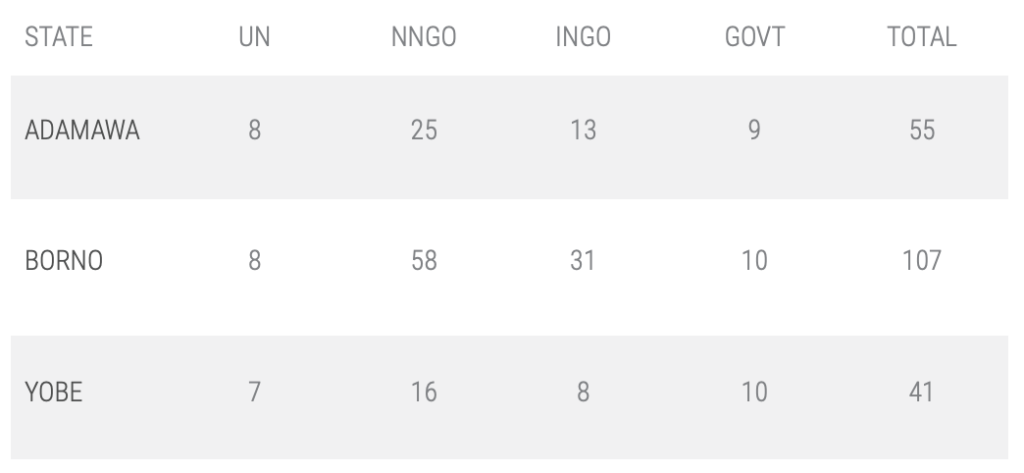

Apart from the federal and state government’s response, the international community as well as local non-governmental organisations (NGO) have given some form of relief or support for victims of the insurgency. However, while aid actors routinely say that relief for the insurgency goes to the so called BAY states (Borno, Adamawa, Yobe), HumAngle notices that within these there are differentials in how attention has been parcelled out. One state out of the three receives more aid than the others; Borno.

This may be with good foundation, the insurgency in the northeast has consistently been more brutal in Borno. But the after-effects of the war have similarly affected victims and survivors in the neighbouring states of Adamawa and Yobe.

There are repeated complaints about hunger and starvation, lack of water and sanitation facilities in camps, cases of sexual and gender-based violence, absence of clinics or health points to cater to pregnant women, malnutrition affecting babies, lack of access to education for children, trauma and other mental health problems, which go unacknowledged in Adamawa.

But according to recent data published by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA) there are exactly 126 humanitarian actors responding to needs. However, as the report broke down actors per states Borno is shown to have more humanitarian partner presence.

Further breakdown reveals that there are 105 aid actors providing inter-sector response in Borno while only 55 are present in Adamawa state.

In the sector of education response for displaced children, the report showed that while Borno has up to 21 actors, Adamawa has seven. In the food security sector, Borno state has 25 actors and 12 in Adamawa. Also in the health sector, it shows that there are 17 actors present in Borno and while there are only ten in Adamawa.

Charity Alaja, an aid worker and governance expert, explains that the aid distribution in Adamawa has reduced gradually over the years because Adamawa ‘is not on the (aid) ladder anymore’, meaning policies are directed at “reintegrating” displaced people to a community, rather than filling dire need with aid handouts.

The UN OCHA data also reveals that there is a significant funding gap between the areas. It states that, “To date, the Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) is 24 percent funded. Of the 1.1 billion USD requested funding, a large majority of sectors remain largely underfunded, forcing response partners to prioritise interventions in communities ranked highest on the severity scale.”

The report also added that, if these gaps are not closed, a number of life-saving programmes across the BAY states will have to scale-down or shut down completely.

Adamawa is, however, said to be at the recovery stage of the insurgency, therefore, “they [displaced persons] should not be expecting relief anymore.” Alaja says.

She adds that, “the funds available for displaced persons in Adamawa are geared towards finding ways to empower and reintegrate them into society. Relief only comes from donors when there are emergencies and in places where crises are still fresh such as devastated communities that are currently facing climate shocks.”

Alaja, who has also worked alongside AD-SEMA at the peak of the insurgency, corroborated the IDPs’ account of the abundance of donated food items and other relief materials when they were newly displaced. “It was an emergency, and the funding for it was available both by the government and aid actors.”

She stresses that access to aid in Adamawa can not be equal to aid access in Borno because aid actors usually respond on the basis of severity and priority.

But it seems as though these changes have not been clearly communicated to the IDPs, leaving them to feel disregarded.

An air of doubt and mistrust

So, depending on a decision made in the heat of fleeing for safety, now a decade later dictates what level of help you may hope to receive.

The inexactness of humanitarian response and lack of transparency has made displaced persons carry a general disdain for anyone who comes to intervene.

This show of mistrust for anyone who does not identify with them comes from years of broken promises amidst dwindling aid. This happens as IDPs are accused of having a sense of entitlement towards accessing relief materials.

When I sat to talk to women about the living conditions in a camp in Malkohi, a middle-aged man walked over to speak to them in Fulfulde, a language he assumed I would not understand.

He referred to me as a government official, warning them against speaking to me, stating that it was a “waste of their time” to indulge people who would never entirely grasp the situation and would not help even if they did. I tried to put them at ease by saying I was not from the government but HumAngle was investigating their treatment.

The man then proceeded to tell how, when he and his family fled from Madagali to the host community, officials of the state government visited and promised to restore 80 per cent of their losses in the attacks. This included losses from properties to food items and other valuables.

Buses were provided for them by the government to take them to their hometowns so they could count things that were destroyed in the war. The gesture gave them hope despite their ordeal.

But when they returned to Malkohi expecting that the government would fulfil their promises within a week or two, not another word was uttered on that plan.

It has been eight years since, and nothing of the sort they promised has occurred.

Bello Hammandila had gone to Lagos, a state in southwest Nigeria, to stay with some of his relatives that resided there at the time. Bello remembers how when news got to him about the government’s promise to compensate them for their losses, he began to find a way to go back to Malkohi so he would not be left out.

“I began to borrow money for transportation, promising people that I would pay in a week. The government had, after all, promised to pay us back,” he sighs. “It took a while before I paid that debt on my own. The promised money never came.”

Resettlement plans on the way

Conversations around displacement camps across the state have shifted from funding for the provision of staple food to the provision of livelihoods and reintegration of IDPs, Charity Alaja explains.

In 2021, the International Organization for Migration (IOM), in collaboration with the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), began a project to support the reintegration of displaced people in the state.

An OCHA report stated that 450 displaced and vulnerable families would benefit from the ongoing construction of the settlement in Labando, a community in the Girei area.

“In addition to a new home, they will receive 216 square metres of land to use however they see fit, such as for agriculture or to build additional structures,” the report said, adding that classrooms, health centres, and a market were also being constructed and would serve both host communities and returnees.

AD-SEMA also tells HumAngle two more resettlement sites have been constructed by the state government in Gombi and Yola.

It is difficult to live in a camp for this long without hope of things looking up, says Bello, who was among the first settlers in the Malkohi camp.

“By merely looking at us, you will see that we are not living well enough. Even when you get enough money and try to farm your food, it does not amount to anything at the end of the day. Before you can cultivate again, you are hungry and desperate for help.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter