Through Crowdfunding, An Initiative Helps Communities Access Clean Water

Originating from Twitter, the initiative used the microblogging site to crowdfund towards addressing water crisis, especially in remote areas of Northern Nigeria.

Adama and her six children would no longer have to swirl their bowls on the water surface to avoid particles when scooping from the stream to their pots. This is because a well is being built in their community at Lere Local Government Area (LGA) of Kaduna, Northwest Nigeria, as part of the #BuildAWell project.

She usually treks for two hours (round trip) to get water from the stream nearest to her community. After making the trek twice a day, she and her family would then have enough to use.

“Sometimes we wake up as early as two o’clock in the morning to fetch water so we can cook, wash, and bathe,” Adama said.

Unlike Adama, Amina’s children are too young to help and she cannot get enough water for the household despite being on her feet all day to get water. “Sometimes I get there and I have to wait for others who were there before me to fetch,” she explained.

The water they get is usually murky with debris floating atop. “Whenever my children are sick, the doctors say it’s because of our water and I believe them because anybody that drinks water from that stream can’t be healthy,” Amina added.

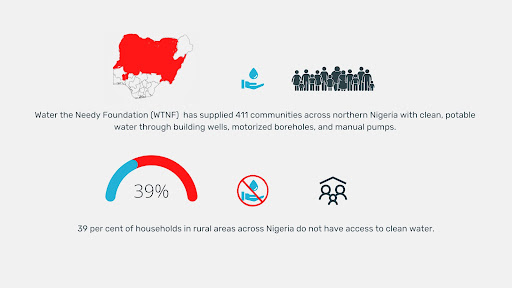

Water the Needy Foundation (WTNF)

When Muhammed Mustapha, the founder of the Water the Needy Foundation (WTNF), set up his Twitter account in 2015, he merely used it the way regular users do; tweeting about his day or an incident or an opinion. It branched out to conveying messages about his faith, Islam, which built up his followership.

It was in 2017 that he came across a viral video of locals in a community fetching water from a muddy river. This caught his attention and also drew his sympathy.

“I wanted to do something from my own end, so I decided to raise funds for them. I posted it on my Twitter and a lot of people donated, even more than was required.” That was how it began.

Mustapha found two other communities and repeated the same method of getting donations. Then a team was put together to find communities without access to clean water. These were not hard to find as 39 per cent of households in rural areas across Nigeria do not have access to clean water.

Mustapha and his team started the foundation which still relies on donations from individuals and now includes motorised boreholes, solar boreholes, and manual hand pumps.

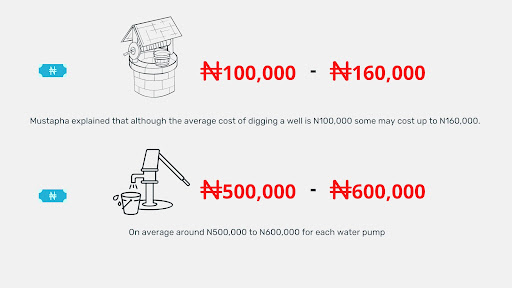

The cost of each well mainly depends on the location because each differs in terms of soil and terrain. Mustapha explained that although the average cost of digging a well is N100,000 some may cost up to N160,000.

Motorised boreholes and manual pumps’ price rates too depend on the environment. “There is a geophysical survey that we have to carry out to ascertain the depth, the number of liters we want to get and the type of pump. These are what determines the cost. But on average we spend around N500,000 to N600,000 for each of them.”

In choosing what source of clean water best suits a community, the foundation tries to understand the geographical size and presence of basic amenities. “When we assess a community and realise they do not have electricity, we usually opt for a traditional well but when the communities are suburban and have electricity we can build a motorized borehole,” Mustapha explained.

The population is also a factor. When a community has a high number of residents, the manual hand pump is built. This is because a traditional well might not sustain them for a long time.

The foundation is now well-known in many rural areas and they get numerous requests to commence a project from community leaders. However, it prioritises communities that experience extreme water shortages.

“When we assess communities and we find there is one with manual pumps in the neighboring village while the other has to walk long distances, we tend to prioritise the latter.”

At the time of filing this report, the foundation has four to five ongoing projects in Kaduna, Bauchi, Taraba, and Kwara states.

Each state has one or two general overseers, depending on how far apart the projects are. Also, for every local government with ongoing operations, there are supervisors who monitor and report back to Mustapha.

The water situation in Nigeria

Poor access to clean and potable water for use in many households across Nigeria has contributed majorly to the spread of waterborne diseases such as cholera, typhoid, and several others.

According to data from Water and Sanitary Hygiene National Outcome Routine Mapping (WASH NORM) in 2019, only 14 per cent of the country’s population have access to safely managed drinking water supply facilities.

The survey also shows that access for people in rural communities is four times less than the population of urban areas. This is due to such supply points being more than 30 minutes away from their homes.

Apart from the rapid spread of diseases, women and children are tasked with the duty of fetching water in distant places which takes a huge amount of their time.

UNICEF reports that when sources of water are not within immediate premises, women and children pay the price of water collection.

While the globally identified causes of water scarcity range from water pollution, drought, climate change, conflict, and migration, which in Nigeria encompasses all depending on the region, the country also suffers economic water scarcity. This means that though there isn’t physical water scarcity, the government does not allocate the necessary resources to evenly distribute clean water sources.

Hence, the major source of potable water is from boreholes and tube wells usually created by individuals or non-governmental organisations like the WTNF.

What the foundation is doing differently

There have been quite a number of regulatory bodies and policies set up over the years with their enforcement and implementation overseen by the Federal Ministry of Water Resources (FMWR), however, these policies have failed to achieve significant strides.

Yunusa Hamza, a water expert, explained that one of the reasons for this is water projects are done without including local stakeholders, which results in water scarcity despite efforts.

This is one approach the WTNF has utilised as their projects, from start to finish, involve district heads, diggers, and supervisors who all belong to the community.

Mustapha said it is one way they keep the community members responsible for the services. “They need these facilities more than anyone. So us hiring people from the community will ensure that the funds donated to them are properly managed and everything is done right.”

Hamza has also identified a lack of reporting mechanisms. “While boreholes and other water sources are built, three months down the line they stop working and locals do not know how to report it to the relevant people who can fix it.”

He explained that in many situations the items needed to restore the equipment are not more than 1,500 naira, yet the facility is left without repairs for years, pushing an entire community into a water crisis.

This is why, when commissioning wells, boreholes, or manual pumps, the WTNF hand it over to community leaders for safekeeping. They are able to reach out to project supervisors who can report to Mustapha for immediate repairs.

Hamza, the water expert, further explained that the lack of reporting mechanism has resulted in about 60 per cent water loss from leaks for up to two weeks with no one to notify officials.

Insecurity and drought

Although the WTNF has carried out projects in Zamfara State, Northwest Nigeria, since May 2017 when the #BuildAWell initiative commenced, there has been no record of wells and boreholes commissioned since Feb. 2021.

Mustapha said despite villages sending requests for wells to be built in their various communities, the issue of insecurity in the region has limited their outreach.

“In fact, there is a donor who has sent us money requesting that we build a manual borehole pump for him in Zamfara but we could not go,” he added.

Mustapha said he respectfully declined the request because he could not risk the lives of his team. “Even though the people there are really suffering from lack of water, the insecurity there is blocking us from rendering our own quota of help.”

He also lamented how some of these communities do not have local diggers and the fear of sending workers there is crippling.

“The process of building a well in some of these communities takes seven to ten days, which means workers have to stay there till it is done and this is really a challenge for us.”

In Kanwa village at Kumbotso LGA of Kano State, Northwest Nigeria, residents buy a substance called ‘alum’ to purify their water.

Ibrahim, a resident of the community, explained that after fetching water from the stream the substance is able to sink dirty elements. “We then collect the clear parts of the water and throw away the dirt.”

Despite their efforts to ensure that families do not fall sick with water-related illnesses, he said there are still incidents where locals are taken to hospitals and diagnosed with typhoid.

Ibrahim said the entire community is grateful for the well dug in their community as it is currently serving more than 50 households in the village.

In a different area, Muhammed Shamsudeen, the district head of Dino in Yorro LGA of Taraba, reported the issue of drought.

“When the dry season started, the well dried up and it had to be restored. Currently, the well is dry again and we are waiting for it to be fixed.”

According to Aliyu, the state’s project supervisor, the traditional well was dug when the rainy season peaked and when the season changed it brought the problem of water absence.

“When we dug it, we could fetch water from it with a cup by merely stretching our hands. That was how it was overflowing with clean water,” he said.

Mustapha also confirmed that the foundation has had to fix a number of wells due to change in season that imposes drought in the community.

Nonetheless, WTNF has set up amenities for potable water in Abuja, Zamfara, Kano, Kebbi, Katsina, Sokoto, Kaduna, Jigawa, Bauchi, Niger, Adamawa, Kwara, Osun, Nasarawa, Taraba, Yobe, Plateau, and Gombe states.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter