This Programme Provides Free Medication For The Underprivileged, But For How Long?

Malaria is one of Nigeria's leading causes of death, but many people in rural communities, such as in its north-central Niger State, do not seek medical care for the ailment, either due to lack of sensitisation or access to medicines. Now a dedicated group of health workers are making an attempt to change the trend.

“We couldn’t take him to the hospital on time because we didn’t have money, and that was why my first child died.”

In April 2019, Halima Usman, 22, lost her two-year-old son to malaria due to lack of funds to procure medications for his treatment. Halima and her husband, Usman Mohammed, live in Garatu, a village in Bosso Local Government Area (LGA), about 20 kilometres from Minna, the capital of Niger State in North-central Nigeria. Like many residents within their economic bracket, they both seek alternative means of treatment whenever they fall sick, usually herbal medicines.

A day before her son’s death, after being ill for about three days, some of Halima’s neighbours contributed money for the family to take the child to the hospital, after days of futile herbal treatment.

“But it was already too late when we got to the hospital.” Halima sobs and wipes tears from her face. “The ailment had eaten him up, and eventually, we were told he died from malaria complications.”

The 2022 World Malaria Report revealed that Nigeria alone accounts for 27 per cent of the global malaria burden. Meaning one in four cases of the world’s malaria incidence happen here. Contributing significantly to this high number is out-of-pocket medical expenditure that discourages care-seeking in hospitals and the use of effective anti-malarials in the poorest households.

The implication is high malaria deaths, as evidenced by the 2016 Demographic Survey, which rated Niger State as having the highest percentage of deaths caused by malaria in North-central Nigeria, with over 19,000 under-five children dying annually.

A second chance

A year after the death of her first child, Halima conceived again, and like her first child, she delivered the baby through the help of a traditional birth attendant. Eight months later, the child fell sick, and Halima would have done what she did with the first child – treat her with herbs.

“But one of my aunties, who is a health worker, visited us and advised that the child be taken to the primary health care facility in the community,” she says. “She told us about free malaria treatment at the clinic. For someone who had undergone the trauma of losing a child to the same ailment, I persuaded my husband to allow me, and I wasted no time in visiting the clinic.

At the Garatu Primary Health Care Clinic, a nurse took Halima’s child’s blood sample for a test. Later, she was told the baby had malaria and given some drugs for her. “My daughter was treated free. I was also advised to always visit the clinic whenever I am pregnant or when my child is sick.” This is possible due to the activities of Global Fund in collaboration with Management Sciences for Health (MSH).

Halting the trend

Niger State is among the states that began enjoying support from the Global Fund to fight malaria in 2018. The Fund is a worldwide movement created in 2002 to defeat HIV, Tuberculosis, and Malaria and also ensure a healthier, safer, more equitable future for all. It raises and invests US$4 billion a year to fight the deadliest infectious diseases, challenge the injustice that fuels them, and strengthen health systems in more than 100 countries.

The Fund began by providing malaria commodities like Rapid Diagnostic Test kits and Artemisinin-Based Combination Treatment in health facilities at the grassroots and in poor communities.

A partner working with the Global Fund to ensure the regular supply of these commodities in health facilities is MSH, a United States-based non-governmental organisation (NGO) that has a decade-long experience in supply chain systems. Through its work, it strengthens existing health systems in collaboration with governments and private sector entities.

A challenge that threatened to derail this progress was theft and wastage of medicines by health workers. The wastages are pronounced whenever the latter treat fever cases like malaria, without running a confirmatory test as the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends.

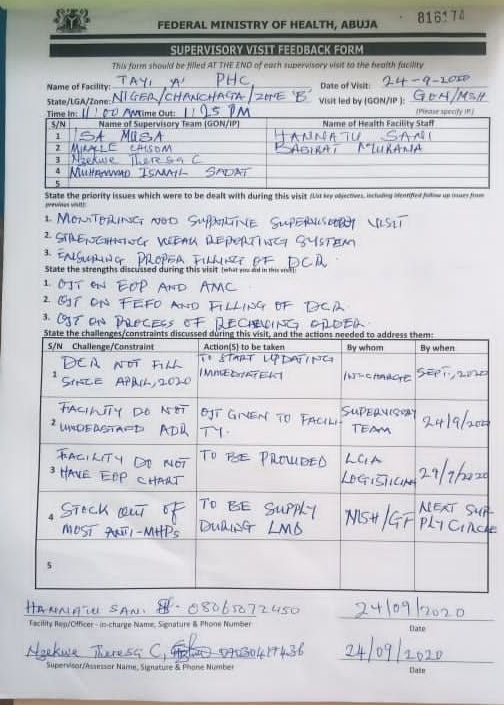

“By setting up systems and training health workers to address these seemingly small but vital challenges, MSH brought the antidote that ensured limited resources in health facilities were managed properly to go a long way,” says Pharmacist Isa Musa, MSH Supply Chain Lead in Niger State.

And a long way they went.

Health facilities who would normally report that malaria commodities were out of stock after a few months began to have stocks in their inventory year-round. This brought huge benefits to such facilities and patients alike.

To be free, malaria drugs must first be available

“The availability of free malaria drugs saved my son,” says Sadiya Imam, a 35-year-old mother whose son, Shuaibu, was diagnosed with malaria at Tayi Primary Health Care clinic (PHCC) in Chanchaga LGA. The clinic is among the 847 out of over 1,400 health facilities across 25 LGAs of the state that are being supplied with free malaria commodities.

“I brought him to the clinic at about 11:30 a.m., and immediately the health worker attended to him. His blood was collected for test in the lab and the result came out positive.”

But Shuaibu was already weak when he was brought to the clinic and had to be admitted and given a drip.

“The malaria in him is already severe,” says Bashirat Nuraini, the malaria focal person at the clinic. “We used to encounter this kind of situation. Parents will wait until their children are so sick before they visit the clinic, and this is a big challenge to us.” However, as services improve, health workers say patients’ visits to health facilities have improved.

Tayi Clinic has experienced an increase in the influx of patients since the start of free malaria treatment, Hanatu Sani, the officer in charge of the facility ,told HumAngle.

“Before the free malaria treatment, the patronage to this clinic was low,” she says. “We only treat 450 clients per month, and most are those on the National Health Insurance Scheme, but now, with the availability of free malaria commodities, we receive about 1,200 clients every month. We run 24 hours service here. Malaria is one of the commonest ailments in this community, and people troop in every day because they know that there is free treatment.”

Like Tayi Clinic, the PHCC in Paiko, Paikoro LGA, is also not left out of the rise in the influx of patients. The officer in charge of the facility, Binta Muhammad, told HumAnle that the facility records over 700 patients, mostly women and children, every month compared to the 150 it received monthly when the free malaria commodities were not available.

Currently, patients’ influx into hospitals in communities that were thought to prefer herbal medical care makes a very important statement: If people know they can get access to medicines and care without stress, and particularly, financial implications, they will visit hospitals and stop self-medicating with herbs.

More patients share experiences.

But while the free malaria treatment seems to have played a significant role in attracting patients, some have other reasons.

“The worker-patient relationship is so good that you hardly hear any complaints about maltreatment or negligence…I will say they like their patients very well,” says Zulia Aliyu, 35, a resident of Angwan Zango in Paikoro LGA.

“Two weeks ago, my son was ill, and my daughter brought him to this clinic because I wasn’t around. But to my surprise, before I came, they had tested the boy for malaria and drugs were given to him. It was only Amoxil and multivitamins that was not available at the clinic that they told me to buy at a pharmacy, but the malaria medicine and treatment were free.’’

The combination of free malaria drugs and friendly health workers won some away from the traditional medicine fold.

There is the example of 25-year-old Fatima Tanko, a resident of Angwan Wadata, also in Paikoro LGA. She was encouraged to visit the clinic while pregnant because of the availability of free malaria drugs but was also provided with health information about how she could deliver safely.

“This was valuable information to me,” she says. “I saw the difference with herbal medicine practitioners who won’t test you, only give you concoctions to take. So, I started going to the clinic when my pregnancy was two months till when I gave birth. The health workers gave me a lot of advice whenever I came for antenatal. Their advice was valuable in keeping me and my baby healthy. I was also given free malaria drugs until I delivered my baby.”

Retaining the patients

“One important support we need is that the suppliers should continue to supply us with medicines because that is what brings more people to us,” says Hannatu, officer in charge of PHCC Tayi. “If we have stock out, we will be in trouble. Many people get to know about the free malaria treatment during door-to-door polio outreach and through community heads, and if they come and we are out of stock, it will discourage them. That will be back to zero.”

Binta, the officer in charge of PHCC Paiko, feels the same way. “We are happy when the drugs are available because we see more people coming to the clinic, and as they receive free malaria treatments, they become happy, and that also gives us joy.”

Like the health workers, patients like Zulia and Fatima hope for a continuous supply of the commodities.

“We want to appeal to the people that are supplying this medicine to continue. We don’t want to come to the clinic, and they will tell us that they [drugs] have finished. This will discourage people from coming,” Zulia says.

Discarding guesswork

Bashirat, the malaria focal person at Tayi Clinic, says the training they received has made it easier for them to provide services for malaria patients.

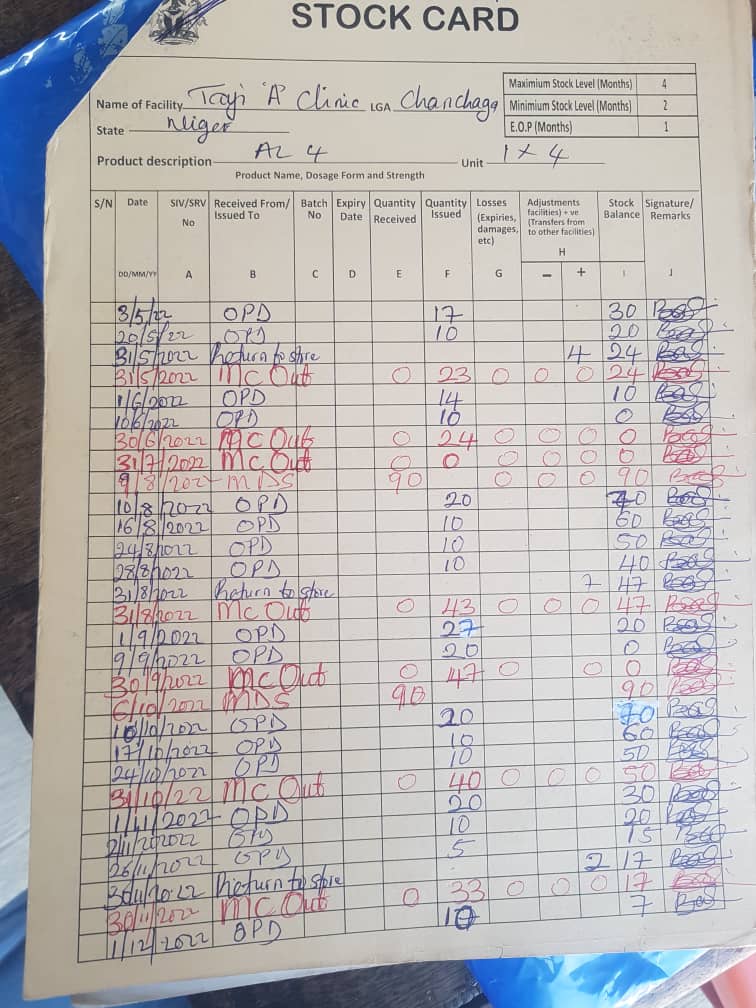

“Before now, we treat clinically, but with Rapid Diagnostic Test kits, we run tests and, if it comes out positive, we administer the drugs we are supposed to administer, and this makes our job very easy. The same also applies to record keeping of the commodities. Imagine when you are just being given a register, and you are not trained. I had to rack my brain to do the job. But now, with training, the job is made easier and systematic. Before now, I just guessed.”

Bashirat knows when the drugs are possibly going out of stock and when the facility is likely to be re-supplied by strictly keeping her daily and monthly records.

“When you are using drugs and you are not recording, you won’t know when it will go out of stock,” she says, “but when you are recording what you are using, you will know when you are likely to be out of stock. You will know what remains and when to make a request.”

HumAngle learnt that asides from handling the supply chain of malaria commodities in the state, MSH also provided training to the malaria focal persons in the health facilities on Logistics Management Information System (LMIS).

“This system teaches them how to fill their stock cards and all the tools they need to use in reporting,” says Pharmacist Mary Jimoh, Niger State Coordinator, Logistics Management Coordinating Unit (LMCU). “The systems comprise some tools that we strictly deploy. We have the Receive Invoice Voucher, the Inventory Control Card (ICC) and the Bi-monthly Facility Stock Report. These three documents are the tools we use to make sure that commodities are being properly monitored throughout the facilities. So, the health workers were trained to properly fill these tools.

Aside from the initial training, LMCU monitors some of the facilities and looks at their records. If they notice any gap from staff, they put them through how to properly fill the forms so that they can get quality reports sent to them at the end of the review period. Using this method, they achieve proper management know,ing what a facility has at a particular time, Mary explains.

“We collect reports from facilities every two months. In the reports, we will know what a particular facility has for each commodity at the beginning of the reporting period – what they receive, what they use, and what they have left at the end. These are the reports that we collect to prepare for the last mile delivery, which is basically the last leg in the supply of medicines to health facilities. And by that, we are able to have feasibility in the system.

“We use a platform presently called NAVISION. In this platform, we enter all the data, and from there, we generate the last mile plan in which we now input whatever we have and send it down to the facility. At present, each health facility sends its report through the LGs logisticians. But we have created a platform or application where each facility can enter its report directly using an android phone.”

Accessing conflict zones

Niger State has been plagued by terrorism in recent times. Some of its LGAs, such as Munya, Shiroro, Rafi, and Mariga, that share boundaries with Zamfara and Kaduna states, have witnessed killings and kidnappings for ransom.

But despite these threats in the affected LGAs, Mary says they still find ways to distribute commodities to the affected areas.

“What we do is to use staff that are within these localities because they understand the terrain,” she says. “We do a kind of proxy delivery to the LGAs headquarters, and from the LGAs, the logisticians find a way to deliver the commodities to the health facilities. In the same way, we harvest the reports from the health facilities. We also have what is called Proof of Delivery. From our office in Minna, we call the health facilities one after the other. For instance, we call facility A and ask what they received from the last delivery. We start looking at the Proof of Delivery as we ask them to confirm their deliveries.”

There are penalties for wastage and the inability of a staff to account for how a commodity is used at the end of the reporting period. Such penalties, according to Jimoh, involve paying for the shortage.

“I recall last year 25 pieces of Rapid Diagnostic Test kits couldn’t be accounted for – imbalance – within our store here, and Niger State Government was made to pay for it,” she says. “So also, in the facilities, if there are things like that, we make them pay for it. This makes people more careful and accountable.”

However, Niger State Malaria Programme Manager, Amina Edward, says improper documentation is one major challenge they face in the management of health commodities in the state. Some of the health workers don’t confirm properly before they receive the commodities from third-party logistics. Another challenge is improper documentation in the ICC card. “But what we do to correct this is to keep reminding them about documentation whenever we visit any facility.”

On allegations that some health workers take the commodities for use at home, she says, “I don’t have that record. No such thing has been reported to my office. If people are saying it, I will say it’s just a mere rumour. I need evidence. It may be true, but I have never caught anyone, nor received any report on that.”

For Pharmacist Mary, the allegation could only be substantiated if they receive incomplete records. “But as long as our data is complete, and we have not caught anybody, such an allegation couldn’t be true. It is only when we go there and the report does not balance up, then we will start to probe. But many times it is because they did not do proper documentation.”

Preparing for end of donor’s funding

One major challenge the state may likely face in the future is how they would cope when donor funds end. Already, HumAngle learnt that there are instances when the state doesn’t get enough supply of malaria commodities from the national warehouse to meet its logistics management plan. And in such cases, the state government must augment it to meet the demand.

“For example, recently the state procured Sulfadoxine Pyrimethamine to augment what we receive from the national,” says Pharmacist Mary, the LMCU Coordinator. “By and large we try as much as we can to ensure that commodities still get to all facilities.”

She, however, adds that even with the shortages they sometimes experience, Niger State is well prepared to make medicines available when donor funds end, due to the system it has already put in place.

“The idea of a logistics management coordinating unit is geared towards sustainability so that when donor funding stops the state will know how to be able to fit in,” she says. “It is not a new thing to them that one day donor funding will stop. The state already has what we call Drug Management Agency, which is saddled with supply chain management. This means that it already has something on ground before the funds are stopped. So, it won’t be difficult for it to fit in.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter