The Tragic Abduction Of Lilian Daniel

It has been over three years since 20-year-old student Lilian Daniel was abducted by members of the ISWAP terror group as she travelled to Maiduguri to resume university. Her mother has been in despair ever since.

There are days when Briskila Kwa’s conviction and faith are strong enough to power her through life. On those days, she would kneel before God, praying fervently, her words long and full of pain and faith in equal measures, begging God to return her daughter to her.

Afterwards, she might be filled with the energy and confidence of one who has asked God for something and received some sort of sign that it would be granted. On those days she can sleep well, she says.

But many times, she spends long minutes, hours, days, and sometimes weeks reliving the day that Lilian was abducted, recognising setbacks they had faced that day in getting her on the road as signs that she should not have offered her daughter to that road that had become so hungry and full of dark men who prowled during the nights and even in the daytime.

The memory always begins the same way; with that phone call Lilian received a few days before she eventually left home for school.

It was her friend who had heard that she was getting ready to return to Maiduguri, Northeast Nigeria, to resume school at the University of Maiduguri. This friend had become concerned and phoned her to register that concern.

The roads were not safe, from what she had heard recently, she told Lilian. Perhaps it was best to postpone going back? Surely the lecturers at school would understand that travelling these days was not as easy as in the years before? Lilian decided she was right. She would delay going back for a while and see whether the news about the road would turn a brighter shade.

And so she waited.

Safe enough

She was 20 years old, living in Jos, North-central Nigeria, and it was Jan. 2020. She had only recently started at the university, studying Zoology, but was home for a brief school break.

The Boko Haram insurgency raged on in the northeast of the country, although it was not as unrelenting as it had been five years before. Jos, while still carrying the scars of the catastrophic religious crisis of the years before, had largely been spared from the fangs of the insurgency. The roads that ran northwards from the city toward Maiduguri remained vulnerable to attacks, however. The Jos-Maiduguri road was especially risky.

Two weeks later, the news about abductions on the road became less frequent, and Lilian decided it was safe enough to go.

After shopping for items she needed for school, Briskila dropped Lilian at the park. The first setback of that day was that no available vehicles were heading to Maiduguri though the place brimmed with people hoping to travel there.

Both mother and daughter found that surprising. But, reassured by the size of the crowd, they decided to wait a little while. Perhaps a vehicle would be provided soon. It made business sense.

After about an hour of futile waiting, however, Briskilla knew there would be no vehicle. And even if there might be one later in the day, it would mean that Lilian would still be on the road far into the night if she did not leave early enough. That was too great a risk, and she told the girl so.

But Lilian insisted she had to go back to school that day.

There was an assignment that she had spent the entire school break working on. It was due the next day, it was part of her continuous assessment that semester. She couldn’t risk not turning it in.

Mind made up

As she and her mother continued to weigh their options, a man approached them and asked where they were headed. They told him. They would not find a vehicle that day going to Maiduguri from that park, he said. However, they could try going to the park that was adjacent to the University of Jos.

They took his advice. As they alighted from the car, they met a stagnant crowd that was almost as large as the one they had left at the previous park. Most of the crowd was headed to Maiduguri or Damaturu, and there was still no vehicle. That was the second setback of that day.

“Even then, I wanted to ask her to just go back home and try another day. But I sensed that her mind had already been made up. So I just kept quiet. We asked many buses there if there was space, but they were all full.”

Finally, they found a mini-bus known locally as Sharon. It was one of those vehicles which had the sole purpose of transporting goods from one state to another.

Mostly, traders who operated inter-state used them to transport their wares. Briskilla sought out the driver, who confirmed he was going to Maiduguri. However, he added quickly when he saw the relief come over her eyes that he was not taking any passengers. He was transporting goods and goods alone. Lilian’s face fell and they stepped away.

After a short while, another empty mini-bus drove into the park, and the crowd ran towards it like a swarm of bees, struggling to get in even though no one knew yet where it was travelling to or if it was even travelling at all. When Briskilla and her daughter approached the vehicle, they learned it was headed to Damaturu and not Maiduguri. Ninety per cent of the crowd withdrew from the car.

But Maiduguri was merely a few hours away from Damaturu. For a short moment, Briskila considered asking Lilian to take the car. But it seemed an unnecessary hassle to arrive at Damaturu and then begin to search for another vehicle bound for Maiduguri.

“Then, a man came and told us to wait, to be patient. He said a car was on its way to take all Maiduguri passengers. He begged us to wait.”

They waited for hours.

Amused

Then, the driver of the Sharon bus who had insisted earlier that he would only be transporting goods, beckoned on them and said he would take Lilian and two other passengers. He had just realised now that he was nearly done loading the bus that he would have space for them.

Briskila looked at the vehicle, stuffed full of goods, and then at the mountain of goods still waiting on the floor and wondered what he meant by ‘he had space’. But she did not argue.

Lilian hopped into the car as her mother stood there, waiting for them to take off successfully before she proceeded to her place of work. She watched as the driver kept loading goods onto the vehicle long after there was no longer space for more. He piled them in the boot so high that he had to use a rope to tie them together because the boot hung open, too stuffed to close its mouth.

And just when everyone thought that was all, the man began to load more goods onto the very top of the bus. By the time he was done, it was difficult to imagine that it would be able to move, but it did.

Briskila was so amused by it all that she stood by a corner and took a picture of the bus with all its goods.

Finally, a few minutes past 10 am, the bus left, and Briskila went to the office.

Shivering

By Briskila’s estimation, Lillian would arrive in Maiduguri by 5 p.m. at most. Lilian always called to inform home as soon as she arrived, Briskila expected her phone to ring at around 5 pm. But by 6 pm, she had still heard nothing. So she called her daughter instead. The call was answered.

“I said into the phone: up till now, you haven’t arrived?”

But it was not Lilian’s voice that came pouring out of the other end. It was the driver’s.

Briskila asked where her daughter was. First, the driver sighed shakily, then he began to stammer in a way that made it difficult to know at first if he was, in fact, whimpering.

They had been accosted on the road, he told her. As she waited for him to explain what that meant, he started to tell her how terribly sorry he was.

“My body started shivering,” she recounts. “I kept asking; what did he mean? Who had accosted them?”

He said it was members of the ISWAP terror group.

Briskilla began to scream, and the escaping scream ran into the questions. She had so many questions for him, and they came pouring out of her mouth even as she became unaware of herself and her surroundings:

Where was Lilian? And where was he, himself? How come no harm came to him? Why was it her own daughter who was abducted? What was he talking about? Where was she taken to?

Over the course of the next few minutes, she learned the details about what had happened in bits: they had been accosted at the Benisheikh-Jakana-Maiduguri road.

The terrorists had disguised themselves as security personnel and waved at him to stop as he drove towards them. He came to a halt. By the time he realised what was going on, it was too late.

They asked the passengers to alight, then ordered him to drive off. They had abducted Lilian and the two other passengers, both men.

In the days that followed, news came that one of the other two passengers had been released.

It was he who told Briskila that they were taken through forests and questioned all the way. They had asked if he was Muslim, and he said he was. Then they asked him to perform ablution and lead them in prayer. He suspected they were trying to see if he was speaking the truth.

That night, they slept under a tree. The morning after, they set him free. They told him which routes to pass and how to find his way back to the main road. As soon as he found himself outside, he went to a police station and reported what had happened. As the news began to spread, it reached Briskila’s ear and that was how she found him.

Then, a few days later, the picture of a young boy who had been killed by ISWAP terrorists started to go around on social media. As Briskila scrolled through Facebook, as she did obsessively, hoping to see if she might find any media article that had reported what happened to her Lilian, she found the picture of the dead boy.

She looked at the boy’s face and found that it was familiar. He was one of the passengers who had been in the same car as Lilian. They had been abducted together, according to the other man who had been set free.

Briskila’s blood ran cold. If they had killed him, they likely would have killed Lilian, too, she thought. She began to wail.

“I cried so much that day,” she says.

Still alive?

Lilian was the only child of her parents. She was Briskila’s foster child, entrusted to her since she was merely a child, but the woman would never admit this fact unless prodded. She loved her as she did her biological children.

Later, she and her husband came to the conclusion that Lilian was still alive. If she had been killed, they would know by now, through pictures or some other way. They set to work, doing whatever they could, as little as it was.

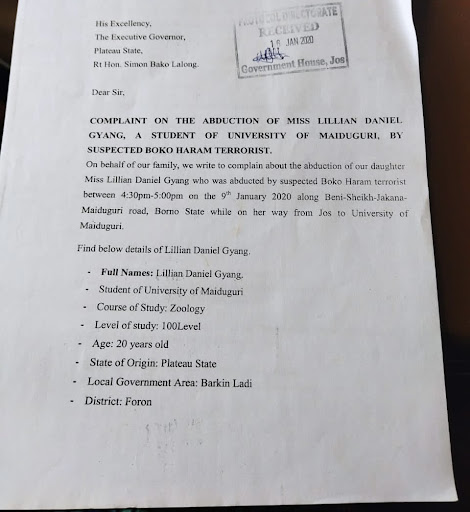

Her husband wrote letters and sent them to the authorities. From village heads to chairmen, political leaders, and even to the governor of Plateau state, Simon Bako Lalong. They wrote to traditional rulers, to senators, to members of the House of Representatives, and to the Commissioner of Police.

Each time her husband submitted a letter and got an acknowledgement copy, they were filled with hope that something would come of it. But the days would pass, and so would the weeks, and they would hear nothing. And they would return to writing letters again.

It has been three years now, and no one of repute has ever reached out to the couple to know what had happened or if there was any progress being made. They have never, even once, heard from Lilian on the phone.

Sometimes, in church, Briskilla would hear that some people had regained their freedom from terrorists, and she would hold out hope that her own daughter would one day be free as well. Many times, she would trace whoever the new escapees were and trace their home, asking if they ever came across Lilian during their days of captivity. The answer was always no.

News

Until one day, at church, she heard that a certain Deborah, a medical personnel who had been abducted months before, had regained freedom and was looking for her.

No one who had regained freedom had ever looked for her. It was always her seeking them out. If this Deborah, whom she did not know, was seeking her out days after regaining her freedom, it had to be that she had news of Lilian.

Briskilla felt herself light up with hope and excitement. She could not wait for the day to come when she would meet the lady. When she eventually came face to face with her, they both burst into tears. They had no previous knowledge of one another, but they each represented to the other a painful, painful memory.

Deborah told her that she had been held captive in the same camp as Lilian. During her captivity, they had got talking, and both learned that they were from the same part of Plateau state.

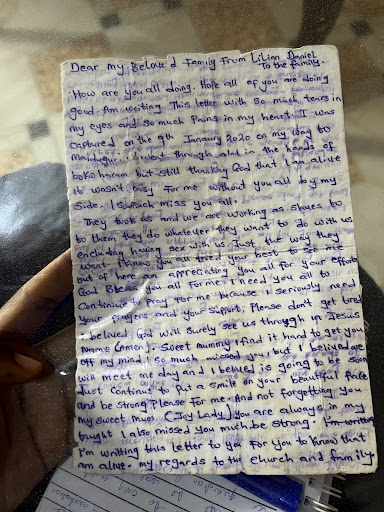

So, they made a truce. Each wrote a letter addressed to their family and exchanged them. If Lilian escaped or regained freedom first, she would deliver Deborah’s letter to her family, wherever they were. If Deborah regained freedom first, she would deliver Lilian’s letter to her family. Deborah regained freedom first.

When Deborah reached into her handbag and retrieved a letter from it, the creases on it showed that it had had to be folded several times into a shape that was as small as possible to be able to fit into a small place.

At first, Briskila’s hand trembled as she collected it, unsure and uncertain of its legitimacy. But then she unfolded it slowly, carefully, to keep it from ripping mistakenly.

And there it was; Lilian’s handwriting.

Tears

It was the most haunting thing she had ever seen. The letter, as well as Deborah’s account, confirmed that Lilian was truly alive.

But it also confirmed something else: Lilian was being abused as a sex slave by the insurgents.

She had learned through her reading it was what they usually did to non-Muslim captives who refused to convert to Islam, and Muslim captives who refused to marry them.

I am writing this letter with so much tears in my eyes and so much pain in my heart… They took us as slaves and do whatever they want with us, including having sex with us just the way they want.

– Excerpts from the letter.

The letter ripped Briskila’s heart in ways she did not imagine possible.

For a very long time, she became consumed by a blend of pain, rage, and frustration. She had heard so much about so many people who had been released, especially health workers and medical personnel who were attached to non-governmental organisations.

Why was it, try as she and her husband did, Lilian was still in captivity? What else did she need to do?

“I am still looking up to God, still trusting Him. We have no one else.”

After the letter, Briskila and her husband intensified their efforts in trying to get help.

They went everywhere, to everyone they thought might be able to help. From missionaries to senators. At some point, they even secured an appointment with the Governor of Plateau state.

They met him and explained things to him. He assured them that though it may not look like they were doing anything to secure their daughter’s release, they were doing all they could.

As this report was being put together, I reached out to the office of the governor through the official Plateau state government website, asking about the case, but received no response. We also reached out through phone calls and a text message to Dr Makut Simon Macham, the Director of Press & Public Affairs to the governor. All went unanswered.

A pastor

Their case began to gain a bit of public exposure. One day, a certain pastor reached out to them, claiming to have some connections that could secure the release of Lilian.

He said he would need half a million naira.

They did not have the money at the time, but somehow they raised it. After some time, the man told them Lilian and a few others had been released but would not be home just yet. If they wanted him to facilitate a phone call between them and Lilian, they had to pay him ₦80,000. They paid.

Later, he said he would need an additional ₦200,000.

By the time it became clear to them that the man was merely taking advantage of their desperation, Briskila and her husband had wasted so much money. Later they learned that duping vulnerable and desperate families who found themselves in the kind of situation that they did was his source of income.

Briskila sought out anyone she heard had either escaped or been freed in an effort to see if they had encountered Lilian. She recalls one particular instance where she met with a girl who had escaped.

They had cried so much when they met that they could not hold any meaningful conversation. The girl’s parents advised that they wait a few days, by which time they both would have calmed enough to talk. But Briskila never quite found the courage to go back, and the girl herself did not reach out.

And so, that was that.

Culture of silence

Gideon William Para-Mallam, a professor and missionary, however, dedicated himself to the case, Briskila says.

Every now and then, he would facilitate meetings between Briskila and any notable person he thought might be able to help. In fact, it was he who helped facilitate the meeting between them and the Governor. He would also call from time to time to know if there had been any progress.

Para-Mallam is a co-founder of the Gideon & Funmi Para-Mallam Peace Foundation, which he runs alongside his wife. It is a faith-based organisation that propagates nation-building and peaceful coexistence.

Gideon confirmed that he had facilitated the meeting with the governor in hopes that it would help secure the release of Lilian. And while the Governor had truly given a sympathetic ear to them, they have heard nothing since of any progress being made.

This is a fundamental problem with governance in Nigeria, Gideon says.

“Even if the government is engaging in silent diplomacy, which is very much allowed, they should be in touch with the parents and should consider giving them confidential briefing so as for them to know what is going on with their loved ones. The culture of silence is very disturbing.”

He explains that some practical suggestions have been given to the government, but so far, none of them has been followed through.

However, he spoke to a lady who regained freedom last year and confirmed that Lilian was still alive, as they had been held in the same camp. That keeps him and her parents going.

Last year, Briskila says, she prayed to God for a Christmas present. She did not want any worldly things, wrapped presents, or shiny boxes.

Just her daughter.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter