The Struggles Of Maiduguri’s ‘Unknown’ IDPs

While the focus has been on formal and informal camps, resulting in their closure by the Borno State Government, host communities in Maiduguri, the northeastern state’s capital, continue to cater to thousands of displaced people that may never return to their ancestral homes.

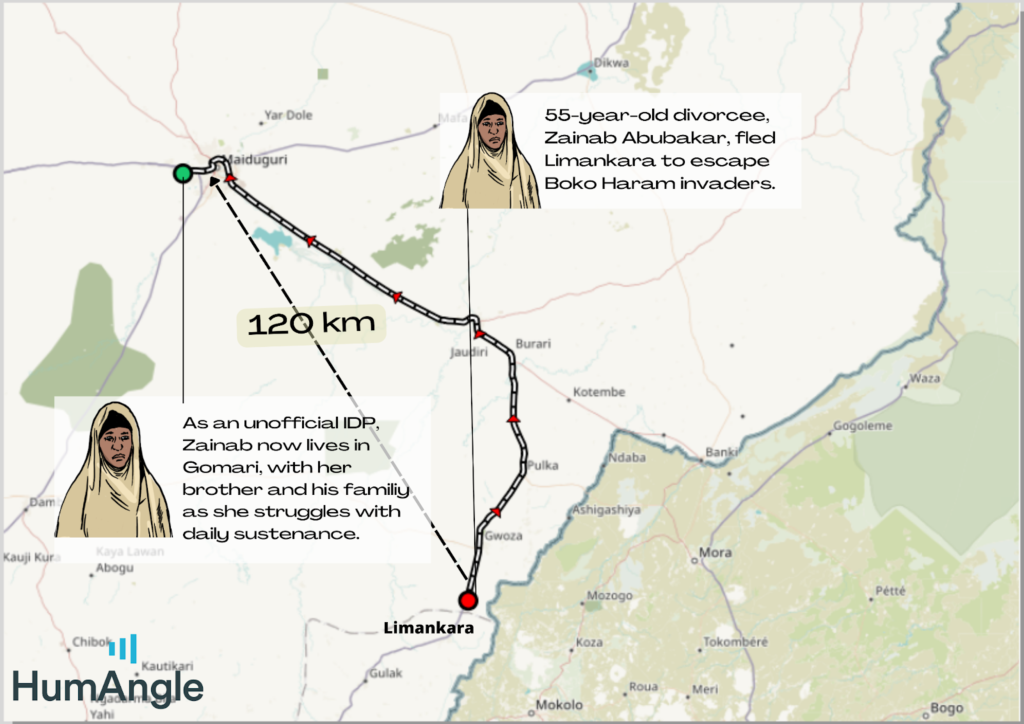

Zainab Abubakar, a 55-year-old divorcee, cannot access humanitarian support from the Borno State government for one major reason – she is not officially recognised as a displaced person. Yet, even now, the memory of how she fled from Limankara in Gwoza Local Government Area (LGA) of Borno State, northeastern Nigeria in 2014, to Maiduguri, the state capital, makes her tense.

“We started running on a Sunday…we slept in Gwoza. We were told the bridge in Mararaban Banki was broken, there was no road. We went round till we reached Maiduguri,” she narrated.

Upon her arrival in Maiduguri, Zainab made her way to Gomari in Jere LGA, a town about 9.6 km away from the capital city. There, she lived with her brother, his wife, and children for two months doing odd jobs. Despite her struggle for a means of livelihood, she was unable to find anything sustainable and long-term. That was until recently, when she got a job as a cook.

“The government has nothing special for us, and I wonder for how long,” she told HumAngle.

Zainab represents many displaced persons in Maiduguri, who are not only unaccounted for, but are also faced with double displacement because they are not officially recognised by state authorities. As such, they cannot access official help.

More of the ‘unknown’

Life would have been much better for Baba Laminu, a retired civil servant, if only he was being given his due as a retiree. Since his retirement in 2021, he has not received any form of payment, either as gratuity or pension. Displaced from Marte LGA, he and his family were unable to secure accommodation at an IDP camp in Maiduguri.

“They [camp] were no longer taking people,” he explained.

Today he lives in Gwange ward where he works as a labourer and also makes and sells caps.

In December 2021, the state governor, Babagana Umara Zulum, had announced the release of funds to settle all outstanding pensions and gratuities in the state, but Laminu, despite the responsibilities he carries as a husband and father of four children, has not seen evidence of this, as his bank account remains empty. This is why he wonders how IDPs are expected to return home and still survive.

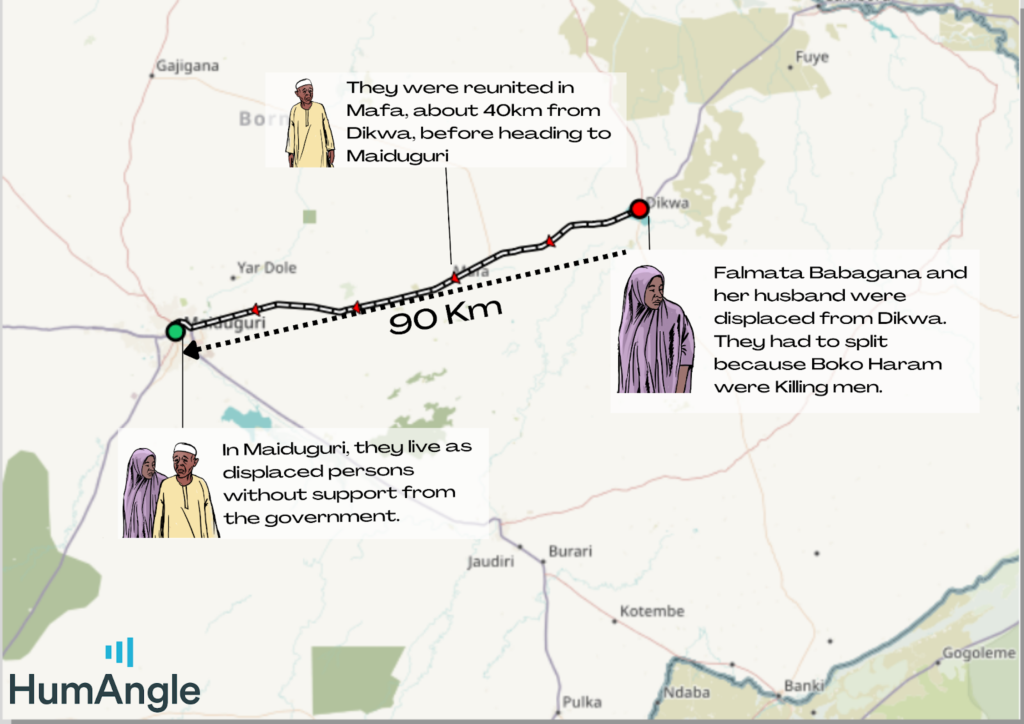

But Falmata Babagana’s case is different. After they were displaced in 2014 from Dikwa LGA and made it to Maiduguri (a journey of about 90.0 km), her husband insisted his family was not staying in an IDP camp. He felt it was unsafe and remained hopeful he could find a source of income for the family’s upkeep.

Falmata recalled their harrowing experience, when she shared with HumAngle in July, 2022: “We started running from Dikwa to Maiduguri on foot. Our men had fled before us, and they left us all behind. We reunited much later in Mafa. During this time, Boko Haram would only capture men and kill only men. And so we took separate directions, so we don’t get caught fleeing.”

Then she paused and pointed out that the government “has not said anything about our children who are out of school till date or us. My husband’s brother pays our rent now.”

Why some refuse to return

An IDP from Ngumati district of Marte LGA, Bukar, like several others, has not returned to his home town despite the government’s efforts to ensure IDPs do.

“The government said it could only settle us in New Marte and not in our hometown, citing security reasons. The facilities it promised to provide are grossly inadequate, especially the feeding system. It makes no difference since we cannot go back home. We are still IDPs, so we should stay in Maiduguri and hustle to survive rather than stay stranded,” he said.

Between 2013 and 2014, the insurgents chased residents in several communities out of their homes. Dije, 32, was one of them. With five children, including a baby, she raced out of Gwoza. Right there in the bush, they met many others like them.

“We ran in circles because there was no clear path. They caught up with us at some point and asked where we were headed,” she narrated.

“We couldn’t answer, so they sent us back where we met the Cameroonian soldiers. We quickly removed our hijabs because they beat women who cover up.”

Afraid, many of the displaced claimed Christian names. That was how the soldiers helped clean their wounds, a result of their running barefoot. They also gave them painkillers. After they had rested, the soldiers showed them a clear path to Humsi village, then Madagali.

“As soon as we entered Madagali, I began to see people I recognized from Gwoza.”

They heard there were official government cars taking people to Maiduguri, but they had no idea where such transportation could be found. So they tried to hitch-hike to Maiduguri. After three days of hunger and pleading, Dije finally got a lift when her baby fainted twice from hunger and thirst. A kind woman helped them to a car that was going to Maiduguri.

“On arrival, I was told my husband had been killed. My hopes were crushed,” she wiped off a tear on her cheek. “The camps in Maiduguri were no longer taking people in.”

Dije, who was used to being provided for, now found it difficult to earn a living on her own. But this had to change.

“I sell coal, onions, and local sweets now to buy foodstuff for us until I can get this house that I can rent, and I pay N15,000 in a year,” she told HumAngle.

Before displacement

“Kaleri has always been a bush; we were eating that day when we heard gunshots, and we left all that we were doing and ran out, leaving behind our cattle, some even their children,” Aisha Usman Buba, 38, began.

Boko Haram had urged her husband to join them or else he would be shot. He refused and was shot in the head. This happened at a time when the insurgents forcefully recruited men and killed whoever rejected their offer.

Aisha lost her children, aged six and 10 – they were killed by stray bullets. Here, as of picturing the past, she fell silent for a little while.

Then, as if propelled by a sudden desire to finish her story, she continued.

“For the whole day, we were in the main town until we heard we could go back again. Most of us came back, while a lot didn’t make it back. My neighbours helped bury my deceased children, and I decided we could no longer live in Kaleri.

But life was not always this brutal.

Aisha Usman was a tailor, and her late husband used to be a farmer. They always had food to eat and even some to give out. “I would sew clothes for myself and our children during Sallah,” she looked up and smiled as tears ran down her cheeks.

Now she has lived in Unguwan Lawan, a community in Maiduguri, with most of the women from Kaleri for over seven years. “Our children don’t go to school. If we eat today, there is nothing to eat tomorrow. We got sleeping supplies from Save the Children organisation once, and since then no one has come to assist us, not even the government,” she said.

Mallam Garba, an executive of a community based organisation, told HumAngle that there are some donor organisations who still provide foodstuffs to IDPs through food vendors in the state capital.

“This package is lucrative, and the IDPs cannot afford to leave such behind to go back home. They would remain in Maiduguri to exhaust their ration for the coming months before deciding on going back home or looking for another opportunity. Other organisations are registering to offer empowerment incentives, and the IDPs are pursuing these opportunities,” Garba said. He suggested that such donor organisations take their interventions to returnees in their home towns. This would encourage others to return.

He added that the government should fulfil its promise to provide adequate facilities in the hometowns of the returnees. “There are gaps in feeding, shelter, water, and sanitation. The government should also provide agricultural inputs to returnees to boost farming morale,” Garba advised.

Security concerns has subsided to a reasonable extent except for isolated cases, he added. All significant routes like Gamboru Ngala, Dikwa, Bama, Bank, Damasak, Monguno, and Baga roads are “freely accessible with minimal security threat. What the government needs is a massive awareness campaign that would encourage the IDPs to return home.”

Their hosts

The elderly and other well-meaning locals have taken it upon themselves to help IDPs in their districts anyway they can.

Although an IDP himself, Sai’d Muhammad Badama provides healthcare services to others as much as he can. In this way, he earns some income.

“I was a nurse in Dikwa before my displacement,” he told HumAngle. “My career is over but I am glad I could help some IDPs medically, even though they are my relatives.”

On the other hand, someone like Alhaji Bukar Isatami, a civil servant and businessman, hosts about 12 IDPs – four from Larai in Martai and some from Bama. “They have been under my care since 2014 up till date,” he said.

To enable him to provide sufficient help, Isatami rented a small apartment to accommodate them. Then he also provides them with food and medical assistance.

Several others told HumAngle how they share scarce resources with displaced relatives and even strangers. Although poor themselves, they do not have the heart to shut their doors to the helpless.

Borno government responds

The Director-General of the Borno State Emergency Management Agency (SEMA), Yabawa Kolo, said both the government and NGOs used to provide support to IDPs in the host communities until the closure of camps in Maiduguri. As a result, the support pattern had since changed.

“I am very sure you are aware that we have closed all official IDP camps within Maiduguri, and the government had provided necessary support and logistics to them as they either return to their host communities or any other safe place for those who decided to remain within or around their host communities,” she said.

“And to God be the glory many of our reclaimed communities are now alive with normal activities as the returnees have settled and are beginning to pick up the pieces of their lives. And despite the official closure of camps and the mass return of IDPs to their ancestral homes – which technically means that any displaced person living in a host community may not be officially recognised as IDP because the choice to remain was voluntary, the government of Borno State, still, has not abandoned them as some of them are wrongly insinuating.

“Just recently, we carried out a massive distribution of food, cash and clothing to almost everyone living in Bama town and the IDP camp. About 40 trucks of rice and maize grain were distributed to thousands of households.

“In Maiduguri, for example, the governor, His Excellency Professor Babagana Zulum, had personally supervised the distribution of food, cash and clothing in line with his target of supporting 100,000 vulnerable men and women within and around the state capital.

“In May this year we carried out the fifth batch of food distribution in Gwange I, II, and III Wards of Maiduguri where a total of 18,000 men and women, mostly former IDPs now living in the host communities, got bags of rice, cash and textile materials.

“Like I once said that apart from what the government is doing, periodically, through SEMA and the Northeast Development Commission (NEDC) we still have other international non-governmental organisations that are carrying out several projects in the host communities and their target beneficiaries are the IDPs.”

Additional reporting by Abdulkareem Haruna

This report was produced in partnership with the MacArthur Foundation under the ‘Promoting Transparency in Insurgency-Related Funding in Northeast Nigeria’ Project.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter