The Performative US Airstrike That May Have Killed No Terrorists in Nigeria

HumAngle merged extensive on-the-ground reporting with satellite intelligence and geospatial analysis to assess the effectiveness of the December US airstrike in northwestern Nigeria. Here is everything we know.

In the evening, moments before the United States’ aerial operation in northwestern Nigeria, a helicopter hovered above the perimeters of Gwangwano District, in Sokoto’s Tangaza Local Government Area (LGA). It was Dec. 25, 2025. Residents said helicopters had hovered around in the past, but this one stayed far too long, unsettling the civilians and alerting the terrorists.

For at least two years, communities in Tangaza have cohabited with foreign-linked Lakurawa terrorists, who first appeared like their saviours. Villagers agreed to a peace deal with the group in exchange for protection from homegrown terrorists who were ravaging their homes and taxing them to death. Initially, Lakurawa seemed more persuasive, residents said, but they eventually introduced their own radical ideologies—far worse than the criminal enterprise they had condemned.

A few hours after the helicopter was sighted, Ardo Kyaure, a terrorist leader in Tangaza, was seen moving house to house near Bauni forests, urging residents to flee. He warned them of an impending attack. Villagers who saw Ardo said he was also making phone calls to accomplices, panting as he ran through the communities.

Ardo was once a local terrorist leader before defecting to join Lakurawa. He became a middleman between the foreign terrorists and the villagers after he was subdued, losing so many of his fighters to the new sect.

News quickly reached the communities that the Lakurawa terrorists were evacuating their camps. Residents said the terrorists fled the area on over a dozen motorcycles. The villagers within the Bauni Mountains and the Kandam community also ran for their lives.

“We sighted 15 motorcycles carrying luggage and the Lakurawa terrorists with their women and children,” Alhaji Rabiu, a resident of Zurmuku, a village neighbouring the Bauni forest, told HumAngle. “Ten additional motorcycles were moving to Muntsaika, a community in the nearby Niger Republic, in the evening before the strikes happened.”

HumAngle spoke to scores of locals who witnessed the air raid, especially villagers living near the Bauni Mountains. We also interviewed village chiefs and a local monarch in Tangaza, who corroborated Rabiu’s account, stating that the strike failed to reach its target, despite public claims by US and Nigerian officials.

“No terrorist was found dead throughout our communities,” said Alhaji Bunu, the traditional ruler of the Gwangwano District in Tangaza LGA. “We saw nothing like dead bodies, even at the Bauni Mountains where the bomb fell. The same Lakurawas we knew are still here, loitering around our communities. We are still mingling with them.”

Fireballs, flaming narratives

A few days after the strike, the Nigerian government claimed “a total of 16 GPS-guided precision munitions were deployed using MQ-9 Reaper unmanned aerial platforms, successfully neutralising the targeted ISIS elements attempting to penetrate Nigeria from the Sahel corridor”. Donald Trump, the US President, had said that the strike eliminated Islamic State terrorists who had been “viciously killing, primarily, innocent Christians at levels not seen for many years, and even centuries”.

That narrative had lingered for years and intensified in the final months of 2025, when the US designated Nigeria a country of particular concern and also threatened military action against terrorists operating within the country. Nigerian officials and security experts, however, dispelled the narrative, saying that Muslims, Christians, and other adherents of other faiths are victims of violent attacks and terrorism in the country. The rhetoric was inflamed again when the US announced that its Christmas Day airstrikes targeted elements of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in Nigeria.

US forces have occasionally targeted ISIS terrorists in parts of Africa, especially in Somalia, often working with local intelligence to combat the violent groups. In Nigeria, however, the strike has sparked fierce debate over whether ISIS terrorists were present at the location hit.

Most security experts agree that Boko Haram and the Islamic State of West African Provinces (ISWAP), which are primarily based in northeastern Nigeria, have established links to ISIS. However, the targeted Tangaza forest, which officials described as the transit hub for ISIS-affiliated terrorists, is known to be dominated by the Lakurawa group, which infiltrated Sokoto through porous borders with the Niger Republic.

Nigerian government officials have publicly claimed that the strike was conducted jointly with US forces, based on intelligence shared to fight terrorism. The country’s Minister of Information, Muhammad Idris, described it as “successful precision strikes on two major ISIS terrorist enclaves located within the Bauni forest axis of Tangaza Local Government Area, Sokoto State”.

“Intelligence confirmed that these locations were being used as assembly and staging grounds by foreign ISIS elements infiltrating Nigeria from the Sahel region, in collaboration with local affiliates, to plan and execute large-scale terrorist attacks within Nigerian territory,” he said.

Yet the circumstances surrounding the strike have raised concerns amongst villagers in Sokoto State and conflict researchers in the northern region.

Was the precision strike successful?

HumAngle began gathering witness accounts moments after the air raid, tracing events before, during, and after the missiles were launched. Residents of Bauni village, where the strike happened, said they have seen no sign that any terrorist was hit.

We interviewed a number of Bauni locals, who had travelled from the village to a safer place in Tangaza to share their accounts. In separate interviews, they all echoed one thing: the terrorists had long left the site of the attack before the missile was launched.

The strike raised curiosity in the communities, as villagers insisted they would know if any terrorist was killed or if any of them were injured.

Kasimu Hassan, a Bauni villager, told HumAngle that the Lakurawa terrorists had absolute control over them, and the airstrike hadn’t ended their reign. In Bauni, he said, no villager was allowed to welcome visitors or accept strangers without notifying the Lakurawa terrorists. He stated that anyone caught doing that could be traced, tried, and executed.

“This has been the situation we are in. Not even a single Lakurawa was killed or injured by the US explosion in Tangaza LGA. Some of them come to our mosques to pray, visit our markets to buy commodities, and stop over at our houses to exchange pleasantries in forceful smiles,” Kasimu said, adding that “the Lakurawa terrorists are still in our villages hanging around the bush even after the explosion.”

At least four other Bauni villagers confirmed Hassan’s claims. One said fires burned in the surrounding bush for days after the strike. Despite official claims that a Battle Damage Assessment (BDA) was underway, locals said they had not seen security operatives surveilling the area for such an assessment.

During our on-the-ground reporting, HumAngle spotted a police anti-bomb squad along the road to Tangaza, but locals insisted that officers have refused to come near the site for any post-strike surveillance. Sanusi Abubakar, the spokesperson for Sokoto State Police Command, has not responded to HumAngle’s inquiry into why the anti-bomb squad has refused to visit the communities for the assessment.

“It was Ardo Kyaure, a terrorist leader, who came to tell us that there is a lot of debris on the Bauni Mountains and another undetonated bomb deposited there,” Kasimu added.

Terrorists taking cover in civilian villages

After the strikes, villagers said the Lakurawa terrorists increasingly sought refuge inside civilian settlements, avoiding the Bauni Mountains, where they usually live. Magaji Abdullahi, the village head of Bauni, confirmed this to HumAngle, noting that the airstrike only resulted in moving terrorists into civilian settlements.

“The mountains used to be our hunting point in the last 15 to 20 years,” said Magaji. “It is not accessible even to our local hunters anymore, except recently, when the Lakurawa terrorists mixed up with us. The Nigerian government abandoned us for years; the only military base available to us was in the far-off town of Gwangwano. They tried a lot in securing only the centre of Gwangwano effectively, but there is no peace in other areas.”

He also stressed that villagers are left with no choice but to cohabit with the terrorists due to the absence of government in the area. The Lakurawa terror group now controls much of Gwangwano District, which encompasses villages such as Bauni, Garin Mano, Mugunho, Kaidaji, and Kandam.

Muazu Magaji, another witness of the strike, had left the Kaidaji village to settle down in the Tangaza town, waiting for the coast to clear. He was there when the missile lightning illuminated the community. Despite the reverberating sounds that came with the airstrike, Magaji said, terrorists were watching from afar, with Ardo Kyaure calling others who might still be around the Bauni forest “to leave”.

“I was walking from Kaidaji to Bauni when the bomb exploded that night,” he recalled. “We already figured out something was about to happen because of the way we saw how the Lawkurawas were moving out of the forest zone to our settlements on the day of the attack.”

After the airstrike, on Saturday, Dec. 26, witness accounts revealed that terrorists came to sniff around to know what might come next. Sanusi Dubudari, one of the fleeing residents from Kaidaji, said: “We saw 11 Lakurawa terrorists in Kaidaji village asking residents whether they found their ₦7 million cash while they were running on Friday.”

Based on several local accounts, the Lakurawa terrorists have blended in really well with the villagers in Tangaza, making it difficult for security to hunt them down over fear of collateral damage. Although the terrorists moved into Sokoto from countries like Mali, the Niger Republic, and Burkina Faso, they have formed a strong alliance with locally-rooted terrorists, who made it easy for them to navigate the terrain seamlessly, sometimes hiding under the shield of locals during military raids. They used the same tactics during the US airstrike targeting ISIS elements in the state.

Apart from Ardo Kyaure, Charambe Damba is another indigenous terrorist working in cahoots with the Lakurawa group. He resided in Illela, a town bordering the Niger Republic, but recently relocated to Bauni to set up a terrorist camp on the mountain and in the forest of the locality. One of the known foreign-linked Lakurawa terrorists is called Asasanta, who is from the Republic of Mali. Other local accomplices were identified as Jammare from the Alela village and Buba Holo from the Gwangwano community in the Tangaza LGA.

Near-surface aerial bombing

HumAngle matched witness accounts with satellite intelligence and geospatial analysis to assess the effectiveness of the so-called precision airstrike. For weeks, we reconstructed the events leading up to the airstrike and what happened later, merging open-source intelligence with on-the-ground reporting. At the time of this investigation, no government or military official (including bomb disposal units) and no journalists had accessed the actual blast site. There were also no photos or after-action reports, which are typically shared on the Nigerian military’s social media channels after air raids.

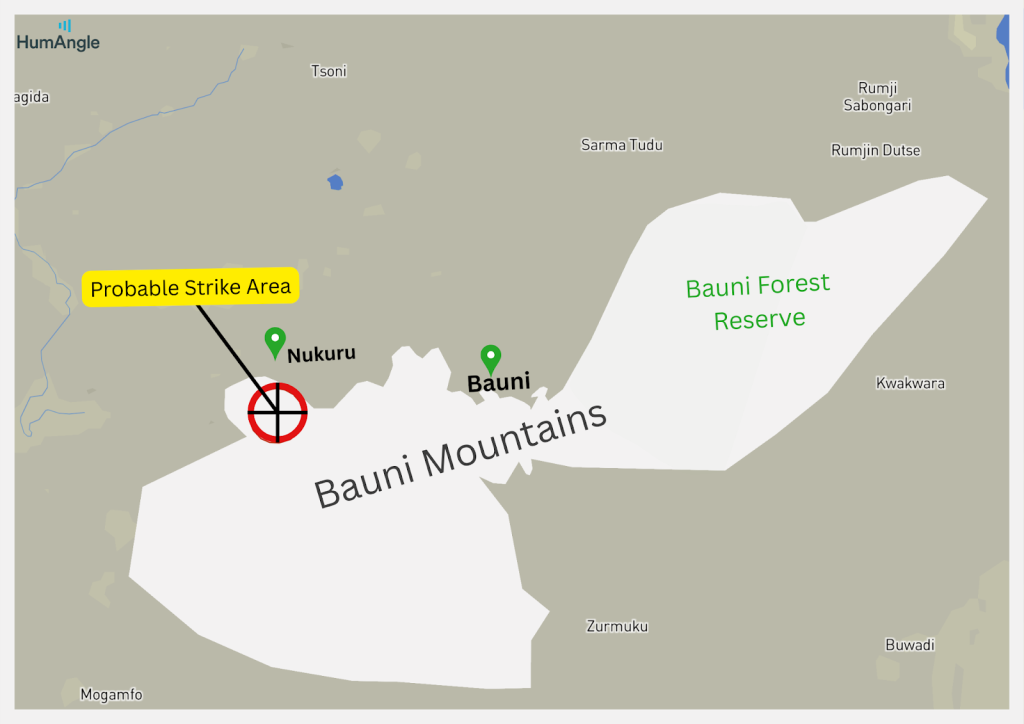

We first used Google Earth imagery as a base map to scan for fire activity that matched the date and timeframe of the strike. With no confirmed coordinates from official or ground sources, we overlaid NASA FIRMS (VIIRS), a US National Aeronautics and Space Administration-run detection tool providing real-time satellite data on active fire hotspots globally. Multiple fire detections appeared about three kilometres south of Nukuru, in the rocky mountainous terrain of the Bauni area. These terrain features matched the location described by our sources and are more than 11 km west of the Bauni Forest Reserve. There were no fire detections deep inside the forest during the relevant period.

From satellite images, the Gwangwano district, including the Bauni village, looks empty. Here, villages don’t spread out; they sit in small clusters, and there’s a lot of space before the next one. Farmland, open savannah, hills, and stretches of land also seem unused. But once you zoom in and start following the details, it becomes clear that the place is just not organised the way a typical rural town would be.

Through extensive geospatial analyses, HumAngle identified recent motorcycle tracks within the Bauni locality – thin lines, sometimes barely visible, cutting through farmland, climbing hills, disappearing into forested areas, and reappearing elsewhere. The tracks were nearly everywhere at the time of this satellite intelligence analysis. One route splits into three, then those split again. Some lead straight into villages, others run around the edges, into the hills, or toward areas where there are no visible settlements at all. This matches what witnesses told us about the Lakurawa terrorists moving on motorcycles in large numbers, and leaving the hill.

Up in the hills and mountain areas, especially around the forest reserve and the expanse of land next to it, there are no villages — just small clearings and faint shapes that don’t look like farmland or houses, with tracks leading in and out. People familiar with this area say these are temporary shelters, where terrorists survive seamlessly, hunting small animals, foraging, and riding into town to buy supplies, and then returning. Here, locals said, terrorists don’t need to live deep inside the forest reserve; the hills and forest-adjacent land outside it are enough. They’re close to communities but not inside them – close enough to reach markets or villages, far enough to stay out of sight.

When we overlaid the NASA fire data from the days after Dec. 25, 2025, the locations lined up with this pattern. The fires were not inside a village, nor deep in the forest reserve. They appeared in terrain that fits how people actually use this landscape — hilly, open, connected by tracks, and close enough to settlements to be seen and felt, but not inside them. However, we found a dense network of informal routes that makes movement easy and law enforcement’s control almost impossible.

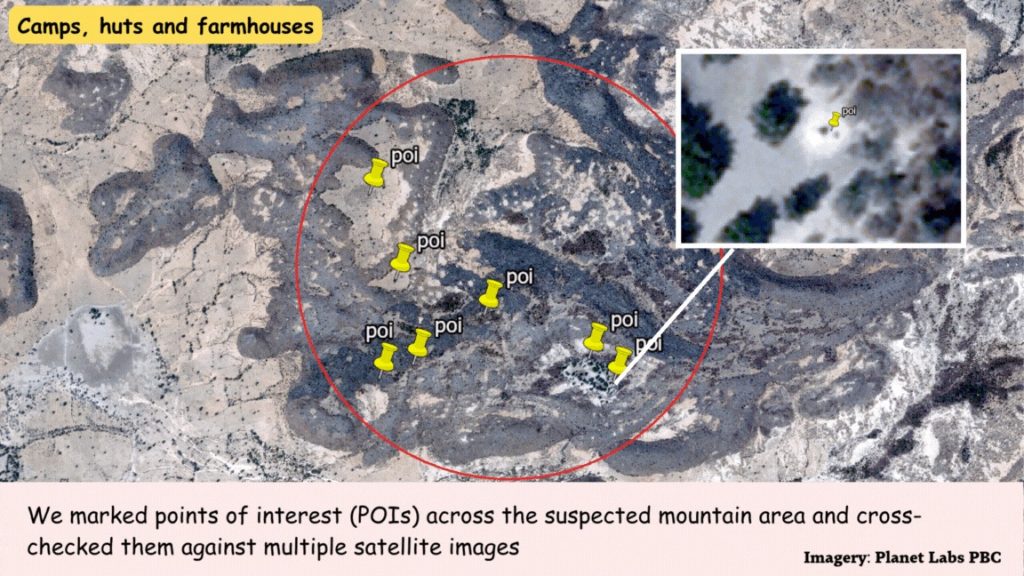

Using Google Earth Pro, we reviewed 2023 imagery of the hills and mountain range south of Nukuru village and the Bauni Mountain and marked points of interest (POIs) across the landscape. The only visible human features in this sparse environment are isolated huts, farmhouses, small clearings under trees, and faint impressions that could be temporary living units. We presented the satellite review to some of the enlightened locals; they believe that if a munition struck a fixed structure there, even a light one, there would be some visible trace.

When we obtained the latest 2025 Planet imagery, we overlaid the same POIs onto the new images and checked them individually. Most structures were still present; some appeared less distinct, likely due to resolution, seasonal change, or abandonment, but none showed clear signs of blast damage, scorched ground, or collapsed structures. In a few cases, huts visible in 2023 were no longer visible in 2025, yet the sandy compound remained intact, without burn marks or disturbed vegetation. This clearly shows that no permanent or semi-permanent structure in the area was directly hit – at least within the limits of our assessments.

The satellite imagery analyses and eyewitness accounts point away from a classic ground-impact strike. There is no visible crater, no destroyed structure, or abrupt disruption of living units. The evidence fits more closely with a high-energy detonation that occurred at or above ground level, producing intense light, a strong pressure wave felt several kilometres away, and secondary fires in surrounding vegetation.

Our findings corroborate locals’ accounts of sighting the flash and feeling the vibration despite being several kilometres from the fire detections. A near-surface detonation transfers more energy into the air, creating light and shock without leaving deep or lasting ground damage.

HumAngle’s satellite investigation shows no clear impact point. The cumulative evidence from witness statements, NASA fire detection, and high-resolution satellite imagery indicates that the US missile strike may not have hit the prime targets.

A recent New York Times story on the incident quoted two anonymous US government officials, who said the strike was “a one-time event” intended to scare terrorists while appeasing the Nigerian Christians that the US has their back, and that the warship responsible for launching the strike has since been withdrawn from the Gulf of Guinea.

Some local conflict and terrorism experts said the US airstrike largely failed to achieve its publicly stated mission. James Barnett, a research fellow at the Hudson Institute, who has researched African conflicts for years, believes that the strike “was performative”. “It was not a success,” he noted. “It may not have even killed any militants. And it certainly did not make Christians there safer (possibly the opposite).”

Seeds of doubt and misinformation

Meanwhile, in Jabo, a civilian community in Sokoto’s Tambuwal LGA, kilometres away from Tangaza, where the airstrike also landed, seeds of doubt and misinformation are growing among residents, who believe that the US is targeting Muslim settlements.

The locals gave accounts of rays of light from flying fireballs and vibrations similar to those of the Tangaza villagers, except that they insisted that the Jabo area does not host terror groups and has not witnessed any terrorist attacks in the past decade. They wondered why such a tactical bombing would be aimed at their peaceful community.

After HumAngle’s report of the residents’ accounts, the Nigerian government provided a counternarrative, saying what locals saw was debris from the air assaults on terrorists in faraway Tangaza. Residents of Offa, Kwara State, also experienced what the Nigerian Information Minister described as “debris from expended munitions”.

Military authorities have urged civilian residents in Sokoto and Kwara to stop keeping the unexploded ordnance found at the sites of the raid. This came after videos appeared online showing locals scavenging exploded and unexploded debris at strike sites in Sokoto, raising concerns about potential deadly blasts.

“We do not expect civilians to pick up or keep such materials,” Major General Michael Onoja, Director of Defence Media Operations, said. “We can only appeal to them to return all materials that may prove harmful to them.”

Media misreporting

Isa Salihu, the chairperson of the Tangaza local council, confirmed that the US-led aerial assault actually hit a known terrorist hub in the area, but stressed that details of the operation were still sketchy. “We cannot yet confirm if targets were killed,” he said. “We are awaiting detailed security reports to determine the impact and to verify if there were any civilian casualties.”

However, some local media organisations in Nigeria erroneously reported the local leader affirming that the “precision strike” hit the targeted terrorists.

A day after the strike, the Sokoto State government, through Abubakar Bawa, the state’s spokesperson, had issued a statement titled: “Nigeria-US Aistrike Hits Terrorist Targets in Tangaza”. But the content of the statement betrayed its title, as it merely reiterated what the local council chairperson said. “The impact could not be immediately determined, as they await assessment of the Joint Operations,” the statement read.

Bawa and the local chairman did not respond to HumAngle’s calls and messages for further clarification on their statements.

In the Tangaza Local Government Area of Sokoto State, a U.S. airstrike on December 25, 2025, targeted ISIS elements but did not achieve its aim according to local witnesses.

Residents and village leaders reported no terrorist casualties, contradicting claims by U.S. and Nigerian officials of a successful strike. The Lakurawa terrorist group, deeply integrated within local communities, avoided detection, with Ardo Kyaure, a local terrorist leader, warning villagers of the impending attack, allowing the terrorists to flee.

The event highlighted misinformation and generated skepticism among residents. Eyewitness accounts, satellite imagery, and open-source intelligence suggest a near-surface detonation with no evidence of direct impact on terrorist hideouts. The U.S. task was labeled as performative by some experts, arguing it neither reduced militancy nor enhanced civilian safety.

Meanwhile, villages outside the immediate strike zone experienced fear and confusion amidst debris, leading to concerns over misinformation and the handling of unexploded ordnance.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter