The Monetisation Of Justice By Nigeria’s Enforcement Officers

The Nigerian criminal justice system has come under heavy criticism from victims and even lawyers on the corruption and monetisation of processes that laws have already made free. Victims told HumAngle they have been framed by Police in the past in a bid to extort money from them.

Tunji Olayiwola was sleeping in his self-contained apartment in the Badore area of Lagos, Southwest Nigeria, when police officers broke in on Jan. 13, 2023, and arrested him.

He was said to have engaged in a fight while playing football on the street a day before. His opponent who sustained injury made a formal complaint with the police.

He was thereafter taken to Langbasa Police Division, one of the stations in the Eti-Osa Local Government Area (LGA) of the state.

At first, the police accused him of being a cultist and locked him up without taking his statement or allowing him to see a lawyer. He was tortured till the following day when a relative came for his bail.

“I was locked up and beaten by the police officers who came to arrest me. They came late at night so there was no way to inform my relatives. It was my neighbour who later informed a cousin that came for my bail the following day.”

He also told HumAngle that other inmates in the cell subjected him to rounds of beating as experienced by many victims of police detention in Nigeria.

When his cousin arrived the following day, the investigating police officer (IPO) brought Olayiwola out of the cell, warned him not to engage in street fighting anymore and demanded ₦20,000 ($28.97) in bail fee.

Corrupt practice

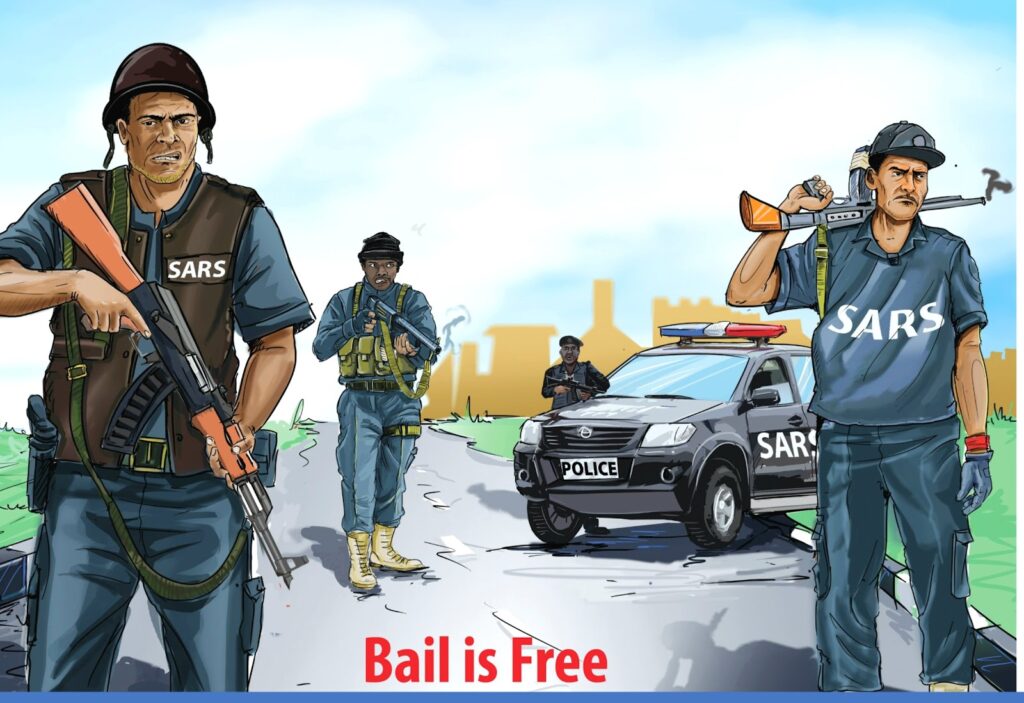

The police have for years insisted bail is free. In fact, authorities at a time embarked on a nationwide campaign to admonish Nigerians not to pay a dime for bail.

To ensure that bail is indeed free, different posters conveying the message were pasted in the crime branch, statement room, charge room and other conspicuous locations in all police divisions, stations and outposts throughout the country.

But that never worked at police stations. Many Nigerians who have passed through police cells told HumAngle they were never released free of charge.

“Money must change hands,” said Olayiwola, whose cousin eventually paid ₦10,000 ($14.47).

HumAngle gathered that police usually ask inmates every morning if there is a relative or friend they want to phone to come to the station with cash for bail.

The frequency of such acts of extortion has led many Nigerians to become complacent.

“You will remain in detention and face charges for offences you did not commit if you don’t pay the police.”

There have been allegations that police sometimes exaggerate the allegations against suspects to drive up their bail, and frame up victims with serious allegations despite the laws – specifically Section 340 (f) of the Police Act 2004 – compels them to exhibit “strict truthfulness in the handling of investigations, and in the giving of evidence.”

Frame up

Unlike Olayiwola, Rasheed Balogun whose mother could not raise the amount the police demanded for bail when he was randomly picked on the street in 2021, said he was framed up for armed robbery and cultism.

Despite denying the allegations, the police forced him to write statements confessing to the crimes and used these confessions to extort bribes from his parents.

Following Rasheed’s arrest, his father, Yusuf, died of depression in late 2021. Afterwards, his mother, Toyin sold all her properties to raise money for her son’s freedom.

Though arraigned in court, proceedings suffered repeated adjournments because the police officer who arrested him did not turn up in court to present any evidence.

After HumAngle’s report on how Rasheed’s mother had spent over ₦750,000 ($1,613) to ensure that he was set free, a lawyer, Ayo Ademiluyi showed interest and Rasheed was granted bail by the court on April 20.

Long walk to freedom

Rasheed did not, however, regain his freedom until June 20 as he was further extorted by police and court officials because he could not get a surety with landed property in Lagos.

But the court secretary stepped in, promising to help him meet his bail conditions if his mother could pay them ₦200,000 ($264.62). After Rasheed’s mother made the payment to the court secretary, a police officer also demanded ₦100,000 ($132.31) to inspect Rasheed’s house in Ajah.

“There have been reports of frivolous charges deliberately filed in the courts by the police for the sole purpose of extorting money from the accused person,” Funsho Adeolu, a lawyer told HumAngle.

“Rasheed’s case is one of many because magistrates sometimes take part in a lot of monetisation of freedom of suspects. It was the reason why the CJN in 2015 warned magistrates to stop commanding rigorous bail conditions on accused persons.”

In his presentation at the Nigerian Bar Association (NBA) conference held in Akure, Southwest Nigeria in 2013, Femi Falana, a senior lawyer, also said that “upon arraignment at the magistrates and area courts, accused persons are made to pay for bail with the connivance of defense counsel. Whereas bail is granted in the open court, it is approved in the chambers of some corrupt magistrates on the payment of negotiated sums of money.”

Other extortion in courts

Though certified true copies (CTC) of court judgments are stipulated by law to be made available within seven days, legal practitioners told HumAngle they often have to wait for months to obtain the copies and sometimes miss the three-month deadline to file an appeal.

According to them, this has repeatedly led to the denial of justice as court registrars and other officials demand unofficial fees before issuing CTC of court rulings.

“I once applied for a CTC of a ruling as a lawyer to the defendant but a judicial officer demanded money to help get it. She said I must pay the mobilisation fee, and she asked me to return in two days. Upon my return, she asked that I pay another money to fast-track the CTC. I saw the judiciary as one of the fountains of corruption,” a lawyer who spoke under anonymity said.

Frustrated lawyer

Speaking on his experience, a human rights lawyer, Festus Ogun said getting justice for both complainants and defendants is heavily monetised in Nigeria.

He explained that aside from demanding money to carry out the arrest of suspects, the police usually take money from relatives to buy detergent used for cleaning cells after bail has been settled financially.

“In a case when matters get to court, complainants still have to pay the police prosecutor less they will make a mess of the matter. Investigating police officers take money before coming to give a witness in court. By the time defendants are granted bail, prosecutors and other court officials charge outrageously to confirm addresses provided by sureties. These officials sometimes would not even go to inspect the houses. They will only collect money from defendants without making inspections.”

He, however, blamed the irregularities in the criminal justice system on the absence of accountability.

Meanwhile, Umar Gwandu, spokesperson of the Federal Ministry of Justice, the legal arm of the Federal Government of Nigeria concerned with bringing cases initiated or assumed by the government before the judiciary, did not respond to HumAngle’s enquiries.

Our reporter encountered the same challenge with Muyiwa Adejobi, Nigeria Police Force spokesperson. He is yet to respond to enquiries on how police officers continue to demand payments to grant suspects bail.

Reform

“We need a complete overhaul of our criminal justice system. Justice should be for all including those that cannot afford their daily meal. The truth is if you are not financially buoyant, there is doom before you in Nigeria,” Ogun told HumAngle.

In his suggestion, Segun Ezekiel, a lawyer, said citizens would begin to have confidence in Nigeria’s justice system if there’s a complete overhaul.

“The administration of justice in Nigeria craves for serious reform so that the last hope of the common man will not be the lost hope of the common man.

“The poor lack access to justice because a majority cannot afford the services of lawyers, and when they manage to get good lawyers, there is a persistent issue of the holding charge. So, we need a reform that requires both cultural and systematic change in the delivery of justice.”

He added that the judiciary has the key to strengthening democracy, hence citizens need an independent, effective, and robust judicial system to count on.

“There is a need for a judicial system capable of guaranteeing individual rights and freedoms.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter