The Divided City (2): How Kaduna’s Warring Badarawa Communities Became Peace Observers

When an interfaith organisation decided to groom Community Peace Observers in neighbourhoods consumed by violent crises in Badarawa, Northwest Nigeria, it turned out to be an exceptional strategy at turning every able-bodied man and woman into a peacemaker.

Imam Muhammad Nurayu Ashafa and Reverend James Movel Wuye should have been sworn enemies. But they had met in 1995 at a gathering organised by the Kaduna State government to encourage adherents of both faiths to take the polio vaccine. That chance meeting changed everything.

Years after that, Unguwan Yero and Unguwan Kwaru, two communities under Badarawa in Kaduna North Local Government Area (LGA), Northwest Nigeria, would clash often. The two clerics, now co-executive directors of Interfaith Mediation Centre (IMC), a non-governmental organisation aimed at resolving conflict, as well as an overwhelming community effort, would play a pivotal role in resolving the conflict. And it would take more than just a sermon.

Weapons of their faith

Ashafa was filled with anger, and it was not without good reason. His spiritual teacher and two cousins, some of the dearest people in his life, had been killed during the 1992 Zangon Kataf crisis that spread to the capital city.

“Initially, both of us [the two clerics] were part of conflict drivers. We were part of the foot soldiers of violence in our societies as young people in the ‘80s and ‘90s. From the Zangon Kataf crisis of ‘92 to Kasuwan Magani crises in 2018,” Ashafa told HumAngle.

“So, we lived in anger and violence was the only language we knew how to use in seeking for a solution. And all this, assuming that we were motivated by religious conviction, until suddenly we realised that it was the opposite.”

In one of these conflicts, Wuye lost a hand trying to protect a church against “unguided” young Muslims.

“On the other side, my colleague was saying they were propagating Islamic tenets and wanting to Islamise Nigeria at all costs. We too were trying to evangelise Nigeria at all costs,” he recalled.

At that time, Wuye worked with the youth wing of the Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN) while Ashafa was with the National Council of Muslim Youth Organisations (NACOMYO). “These bodies never saw eye to eye, so that tension was on before the chance meeting of 1995 which is our journey now of 27 years of working together as peacemakers, turning our enemies into friends,” Wuye added.

A change of heart

Ashafa’s rage drove him to the point where all he wanted was to retaliate and avenge the death of his loved ones. Then something happened to him.

“I went to the mosque and the Imam was preaching about the power of forgiveness. And I thought, ‘How can I love my enemy?’ Because the Imam was saying the ideal way of becoming a true Muslim is to love your enemy by using the power of forgiveness. And he told us about forgiving the unforgivable, people who hurt you, who aren’t convinced they are doing the wrong thing and feel what they do is right. And they are not apologetic,” he narrated, his voice soft as he spoke.

When the preacher further told the story of Prophet Muhammad and his depth of forgiveness, Ashafa was moved.

“That word touched me. The Qur’an went on to tell us to turn enmity to forgiveness. But you can only do that if you have perseverance. That enemy would turn out to be the best of friends,” he said.

So, that fateful year of ’95, during a coffee break, the two young men, Ashafa and Wuye, were encouraged by Malam Idris Musa, a journalist with the Kaduna State Media Corporation (KSMC) to chart a different course.

“That was when the journey started,” Wuye said.

Today, Ashafa calls Wuye his twin brother, a man that “used to be my worst enemy in the ‘80s and ‘90s. He is a Pentecostal evangelical Christian who saw nothing good in someone except those who believed in his position. I was then part of the Muslim Youth Council as secretary-general. I was also furious and believed it was the only way to address our challenges.”

So far, the two men have won multiple awards across the world, such as the German African Award for Peace Model, United Nations Alliance for Civilisation Award for Role Model of Interfaith Cooperation, other peace prize awards and honourable doctorate degrees from India, United Kingdom, and the United States.

“Just because we learned to use religion positively,” Ashafa pointed out.

Fixing broken communities

Under Ashafa and Wuye, IMC has toured the country to mediate conflict situations. A typical example was in Plateau State in 2021 where they got express permission to visit communities despite the imposed curfew.

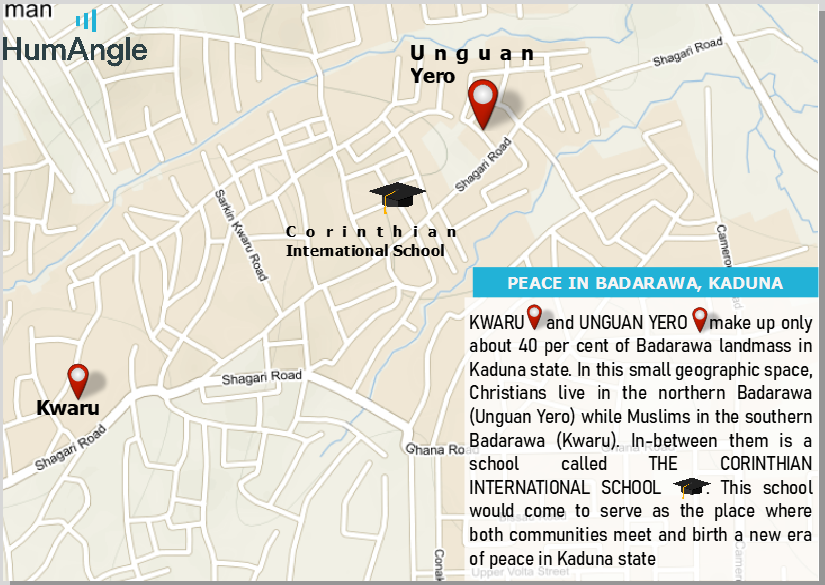

Back in Kaduna State, some of their work included settling the ethnoreligious crises in Kasuwan Magani of Kajuru LGA. Then there was the case of Badarawa’s Unguwan Kwaru and Unguwan Yero, two warring communities in the state capital divided along religious lines. Although both communities are under Badarawa, the predominantly Muslim settlements are mostly referred to as Badarawa while the other is identified by its name – Yero.

Ashafa explained that whenever there was violence between Badarawa and Yero, Muslim and Christian youths on both sides, who are mostly drug addicts, become the foot soldiers. “And the communities encourage them to kill those who cross over to their side.”

Noting the pattern, IMC created a “peace structure” that involved training the youth as Community Peace Observers (CPO). By that time, the communities themselves were tired of the conflict.

They are trained on “peace communication” and given a tool on how to avert conflict situations by using the culture of non-violence. Even when they defer, they choose a different way of expressing themselves.

Communities currently operating this peace structure include Badarawa and Kwaru; Unguwan Gabas which used to be at loggerheads with Unguwan Rimi; and Nasarawa and Tirkaniya. “These are areas where you see Muslims and Christians on opposing sides. But this has changed,” he pointed out.

The peace observers

In the Badarawa area, youths like Zakariah Muhammad (a Muslim from Badarawa) and Moses Ayuba (a Christian from Yero) make a strong team as leading CPOs.

Muhammad, who is coordinator, Kaduna North Committee Peace Observers, and a youth leader under the LGA, pointed out that the conflict between Unguwan Yero and Kwaru was usually responsible for the spread of conflict across the entire state.

Although there were interventions by several organisations, he emphasised the IMC played a more significant role.

“We started running programmes aimed at building trust that have continued for about five years now.” These include training, workshops, and other community initiatives.

In Jan. 2016, Muhammad started work with IMC in Barnawa, Kaduna South LGA. He was among the first set of 120 CPOs selected, with 30 persons each from Barnawa, Unguwan Rimi, Unguwan Yero, and Unguwan Gado. The training led to monthly programmes spearheaded by the trainees.

“Those trained now went back to their various communities to train others,” Muhammad said. “We have currently trained up to seven sets of people. Sometimes we train up to a hundred in a set and it’s still ongoing. Within a period, we get to train as many as 600 people because we carry out different kinds of programmes.”

If there is a programme organised by IMC, Ayuba as a lead member of the CPO in Unguwan Yero is saddled with the responsibility of organising youth from his community. This also applies to Muhammad.

Alice Paul, 48, another CPO, plays a valuable role among the women in Yero. Formerly a resident of Badarawa, she had fled in 1992 during the Zangon Kataf crisis that spread across the state.

“Back then, we were doing everything together with Hausas [in Badarawa]. We celebrated with each other during Christmas and Sallah festivities.

“But peace left us in ‘92 and everyone began to look for where their own people were in the majority. That was how I came here [Yero].”

It was in Yero that Alice became a CPO. She eagerly joined because she felt it would help the communities. This was how the women now set up a forum for Christian and Muslim women. They began to hold a series of meetings centred on peace-promoting strategies.

“Of particular interest to us were our children who were into drugs, because they were at the forefront of every conflict,” she added.

Twenty-two-year-old Habibu Sanusi, born and bred in Kwaru, corroborated Alice’s words. Currently a CPO too, he recalled how things started changing in 2012 as a result of the activities of drug handlers. “But it was always given religious colouration,” he said.

Then groups such as IMC, Mercy Corps and the Association of Regional Development Agencies (ARDA) came to the rescue. As a Community Peace Observer, if conflict erupts, Sanusi is expected to let relevant authorities know early so it can be curbed. As a result, he stresses, there has been a reign of peace for a while.

“Right now, we are back to playing football and doing other sporting activities together,” Sanusi added with a smile, “Including watching football at viewing centres and attending the same schools. Our parents on the other hand now hold occasional meetings. If a child does something wrong, his attention is drawn to it, unlike when religion was attached to every issue.

“Almost every locality has a civilian joint task force (JTF). They cut across the two faiths and handle any indiscretion.”

Whenever a crisis broke out, the women focused on ensuring their children were not a part of it. Their forum liaised with traditional leaders which produced positive results. The moment conflict erupted, these leaders put their heads together and quelled it.

“Our headache used to be the youths. Sometimes when we are sitting you will hear that some youths from here are starting a conflict. Then you hear there’s another from another side. But things have improved,” Alice said.

“Before now, you could hardly see someone from Yero go into Badarawa. If you went in there, you wouldn’t return in one piece. It was the same for someone from Badarawa who came to Yero.”

Today CPOs continue to increase in number, a strategy that aims at making every youth a peace observer in his or her community.

Clerics rise up

Kaka D. Sunday, 41, a member of Unguwan Yero’s civilian JTF was three when his family came to Yero in 1983. He recalled how Muslims and Christians used to live peacefully until the 2000 sharia crisis.

“We used to do business in Kwaru freely. End of the year harvest and bazaar used to be held in Saint Rita’s Catholic Church and both Christians and Muslims would attend. I have Muslim friends that I am together with to date,” he said.

Yet, the sharia conflict, Sunday emphasised, was what shook the two neighbours. Then Unguwan Yero, Kwaru, and Badarawa had become overpopulated and there was no longer trust between members of the two faiths.

It did not end there. The 2002 Miss World crisis further strained the already weak relationship. “Many were killed and properties destroyed. Drug addicts now used it as an excuse to always fuel conflict.

“Then in 2011, during the government of late Yakowa, a confrontation that didn’t last for three hours took place, but there was a lot of destruction. On Monday a curfew was placed, on Tuesday morning it was lifted, and that was how people were killed. This further tore us apart.”

Sunday mentioned another incident at a bus stop where the stabbing of one person led to senseless killings. In the end, the root of the violence remained a mystery.

“The most recent was in 2019 where someone went to buy illegal drugs. It seemed like he was a dealer. His property was taken from him and after about a month he saw those who snatched it and that was how someone was stabbed to death. This also led to violent conflict.” And the circle of violence continued.

This was when the communities in the Badarawa area finally came together at Corinthian school (a major junction that served as a boundary between Yero and Badarawa) and said enough was enough. Clerics gathered there, and that was when the journey to peace started, Sunday told HumAngle.

“That was when IMC came in, organised a programme and invited us.”

The JTF effect

Sunday pointed out that another important role towards ending the conflict was played by the civilian Joint Task Force (JTF) of which he was a member – both those at Badarawa and Malali.

“When JTF in Badarawa catch a Christian committing a crime, just so no one says there is bias, they hand him over to Yero JTF.

“Even if I am asleep today and someone from Yero does something wrong in Badarawa, Kwaru, or Tashan Kanawa, they would call us. We also do the same. Before now, a Muslim wouldn’t dare buy a house here, but there are now some here. We had an issue with some of them recently and decided to take it to Sarkin Kwaru, because we [Yero community] are under him. Just so it would not be given religious colouration. He told us to continue to use such an approach without delay.”

Today, Christians can go to Badarawa and Muslims from the latter, including Unguwan Dosa and Hayin Kogi, can come into Unguwan Yero, Ayuba points out.

Before now people from Unguwan Kwaru hardly came down to Unguwan Yero. Also, those from Yero had to use Unguwan Gado or another route. But this has changed. Christians can now go through Badarawa-Kwaru and from Unguwan Dosa down to Legislative Quarters all within the LGA.

“Now I use the long stretch of road through Yero as my shortest route. The road connects the two communities. If the politicians understood this, they would have tarred it,” Muhammad added with a smile.

Collective losses

In 2012, Kwaru, which was a mixed community, was under curfew for seven days due to crises, Abubakar Lukman, a Kwaru resident, said. “It disrupted business and then relationships.”

There was also the loss of human lives. Some residents like Friday Ayuba’s father heard that they had killed Friday’s elder brother. So, he rushed to the scene only to be seriously wounded. Luckily, he survived and later realised his son was still alive. “But I lost my brother-in-law in the crisis,” Ayuba said.

Others, like Anthony Augustine Giwa, 38, lost his immediate elder brother in 2002. Then his uncle. But instead of letting hate eat him up, he looks elsewhere. He is now part of a 13-man peace and development committee in Yero. Like Ashafa, he too has moved beyond his pain and embraced peace.

Giwa lays the blame at the feet of those he called marijuana smokers at the riverside. “Then they extend it to the community as a religious issue. And whenever you mention the two religions in a conflict you don’t expect peace except you are opportune to have the right people who would handle the situation,” he said.

Loose ends

In their effort to unite Kaduna, IMC worked with religious leaders and came up with the Kaduna Peace Declaration of Religious Leaders.

“It took us five months to work with religious leaders to agree on everything in that document. We borrowed the document from the Alexandrian Declaration, which is one initiative that didn’t work between the Israelis, Palestinians, and Arabs. We took it and contextualised it to the Kaduna situation and it gave the result we wanted, nine years without interreligious and inter-ethnic hostilities till the post-election violence of May 2011,” Wuye told HumAngle.

Yet there is still more work to be done. This, he said, is due to the lack of political will on the side of the government.

“One government comes and is more disposed towards having civil societies work in this regard; another comes and keeps them at bay.”

Wuye pointed out that IMC has done its best. It drew a topographic map for the government and society on how to reach a permanent solution. A typical example was when it suggested to former governor Ahmed Makarfi to set up a bureau of religious affairs with a director or permanent secretary for both sides. This worked for a while, but successive governments did not build on it.

“Our joy is that some of the recommendations and some of our activities, even if not attributed to us, are being taken by the government and we are happy. The more peacemakers the merrier,” he said.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter