The Divided City (1): Kaduna Residents Reminisce Lost Relationships

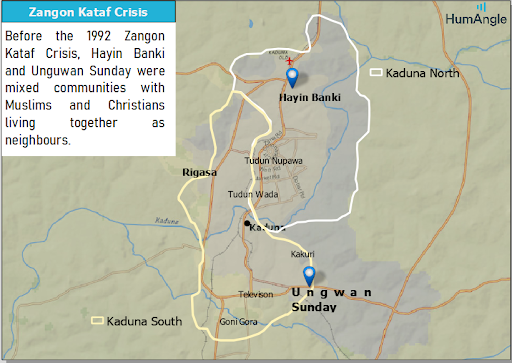

The division along religious lines in Kaduna, Northwest Nigeria, became significant in the early 1990s as a result of the Zangon Kataf crisis, and then deepened after the sharia conflict in 2000 and the Miss World riot in 2002. But today, many residents miss the way life was in the state’s capital city.

Muhammed Muhammed, aka Coach DK is a popular man. A football commentator, he has lived in Hayin Banki, currently a predominantly Muslim community in Kaduna North Local Government Area (LGA), Northwest Nigeria, long before it blossomed.

“I was about seven years old when we came here,” he says, “and there were less than 10 houses then.”

Like Muhammed, Adamu Danladi, 48, was a boy in 1984 when he came to Unguwan Sunday, now mainly a Christian-dominated area in the state’s Chikun LGA. He finally settled there in 1994.

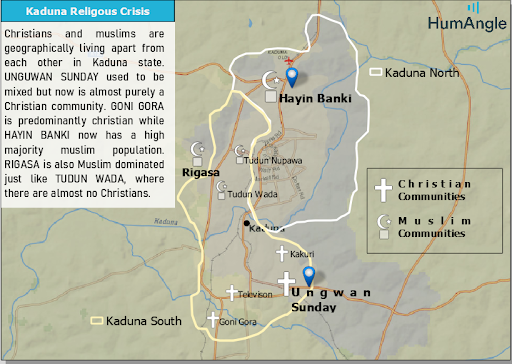

Muhammed is Muslim and Danladi a Christian. Back then, Hayin Banki and Unguwan Sunday were mixed communities with Muslims and Christians living together as neighbours. But this later changed with most Muslims relocating to the city’s north and Christians to the south. Today, members of both religions can only live where they are a minority with some sense of caution.

Road to disunity

Although there was an outbreak of violence in 1997, the division along religious lines in Kaduna became pronounced in 1992 as a result of what came to be described as the Zangon Kataf crisis. That year, a clash broke out between the Hausa (who are mainly Muslims) and the Atyap (a predominantly Christian ethnic group) in Zangon Kataf, “initially sparked off by a dispute over the relocation of a market. Killings of Hausa by Kataf were followed by reprisal killings of Christians by Muslims, including in several other parts of Kaduna State.”

Then to make matters worse came the crisis of February and May 2000 where “2000 people, and possibly many more, were killed in fighting between Christians and Muslims in Kaduna.” This was fuelled by the debate around the proposed introduction of Sharia in the state. Although Sharia has been part of Northern Nigeria for years, until 1999, it had applied mostly to personal and not criminal law.

While the state was still licking its wounds, Nigeria became the chosen location for the Miss World pageant in 2002 and the world’s spotlight fell on the capital, Abuja. But a comment by Isioma Daniel, a columnist with ThisDay newspaper, suggesting “that Prophet Mohammed would approve of the contest and … that he might marry one of them” cut short the nation’s excitement.

The article led to the burning down of the newspaper station in Kaduna, after which the youths “set fire to churches and attacked bystanders thought to be Christians while chanting ‘Down with beauty’ and ‘Miss World is sin’ for three days.”

According to the Red Cross, more than 500 people were injured and over 100 died in the riot.

There were several other clashes apart from these three major conflicts in Kaduna State that continued to tear the once relatively peaceful and homogenous city along religious lines. However, historical records show that, since 1980, violence fuelled by these divisions has claimed about 20,000 lives.

Memories

So, as the years glide by, Muslims recollect the killings on the other side of Kaduna’s major bridge in the south and, Christians the memory of being caught in the city’s north during the chaos. But it’s been long now since there was any major upheaval that can be tagged a ‘religious crisis’ as terrorists, locally called bandits, take centre stage in the tragedy that lays siege to the northern region’s former political capital.

Today, some residents on both sides of the city reminisce over the good times, and one of them is Muhammed who grew up in Kaduna North’s Hayin Banki.

“For about five to 10 years, all my friends were Christians and for this reason I faced challenges from some [Muslims],” he says in Layin Bakin Dogo, a neighbourhood once populated by people from both faiths. “Life was good and probably better than what it is now because there was no segregation.”

To illustrate this, Muhammed talks about how he once left his house door open overnight only to return and find things the way they were. “I slept over in Matthew’s [a Christian’s] place. He worked with a textile company in Kakuri then.” Peace, he explains, was evident until towards the end of the ‘90s.

Muhammed also remembers how he once wore his father’s babban riga on Christmas day, looking, he says, even better-dressed than his friends. He could see the admiration in their faces as they went out together.

“And because we Muslims don’t eat meat when it’s not prepared in a certain way or without a certain prayer, they [Christians] got a Muslim to slaughter it so there won’t be any doubt.”

That was not all. Muhammed opened his doors to many friends in his youth, and some left his home to clinch lucrative jobs. Friends like Friday, Papa, Kaura, Godwin John, Confidence and several others who grew up with him. Currently he struggles to keep those relationships.

Some of his friends, like Godwin John, now live in Gonin Gora, a predominantly Christian community. “He’s one friend I miss. We lost contact once, later we rekindled the relationship but I don’t feel safe going to his neighbourhood, so that affected our relationship.”

Then again Muhammed recalls when John’s wife died and he was one of those who travelled with the corpse to the burial destination. This was the kind of relationship they shared.

Fear for the future

Danladi is afraid for Kaduna’s upcoming generation. He is uncertain if today’s Christian and Muslim children will be able to “tolerate” one another. In his youthful days, they attended the same schools, traded in the same markets, lived in the same neighbourhoods, and played together in the same football clubs.

“We were able to live with one another, even after the crises that threatened our unity. But all this has changed now,” he says.

“If you go to Unguwan Sunday today, you will find very few Hausa Muslims trading. There are purely Christians buying and selling. Our children now have near to zero interaction with Muslims. They grow up with a biased mind. The level of tolerance is a thing of concern. It will take the grace of God for them [both Christians and Muslims] to be able to live together.”

Danladi recalls when some of his Muslim friends followed them to church and sat quietly.

“There is one Muslim neighbour, Dan Funtua, who has refused to leave since the ‘90s. He grew up here. During the crisis, Christian neighbours shield him,” he points out. “Some Muslims do the same to their Christian neighbours elsewhere.”

But Danladi makes an observation: “I notice that the Muslims easily adjust, unlike Christians. After the crises, they sometimes return to where they live or do business. But since Christians left Tudun Wada or Rigasa, you hardly see them doing business there.”

The city became more segregated after the Miss World crisis, “when most of the Hausa people decided to leave, and then others from the northern part of the city migrated to the south. So, as some were moving out, others were coming in.”

Danladi says between 1998 and 2000, that a lot of Igbos, Idomas, and other people from other ethnic groups bought houses built by Hausas. Eventually, there was a total transformation and Unguwan Sunday became a Christian-dominated settlement, with the exit of almost all the Muslims.

Unguwan Sunday has an interesting oral tradition that dates back several decades. Sunday, the man the settlement was named after, was an Igbo man and the first settler, he narrates. “He sold bicycles and ogogoro or local gin. So, people from Television and Kakuri crossed to Unguwan Sunday and said they wanted to see Sunday.”

Nostalgic, Danladi keeps some memories close to his heart. Names of neighbours and friends like Bala, Danjuma, Dahiru Ibrahim, and several more stay with him. Amongst them is one he has the privilege of having contact with because they work in the same organisation. For some residents in his shoes, it is work and travel that connects them with those not of their faith.

But Tanko Auta, Unguwan Sunday’s Sarkin Kudu (King of Unguwan Sunday South) has a different story to tell about the settlement. He explains that Unguwan Sunday was named after a Tiv man who worked in a railway company in the area and the first Mai Unguwa (village head) was a Hausa man from Katsina called Sani Muhammed (a Muslim).

“It was after his death that I became Mai Unguwa in 1979 and then king in 2005. I was born in Kujama and relocated to Kakuri and then Unguwan Sunday in 1972,” he says.

“When I came, there was no church and I set up the first one. Everyone practised his religion peacefully. There was no discrimination at the time. It was in 2000 that the division began. But the 1992 crises had already affected us by then. In Romi and Television, there were crises but not in Unguwan Sunday. Today we are not enjoying Unguwan Sunday the way we used to.”

Social media to the rescue

Thirty-five-year-old Ashidi Mamman and his family had relocated to Unguwan Sunday from Kafanchan in 1993. This was just after the Zangon Kataf crisis when Kaduna was still trying to recover its lost glory. Yet, there was still a great mix of people from different ethnic groups and religions at the time.

“The issue is not with residents but with people who instigate the crisis. There are Muslims and Christians who desire to live in peace. Those who bring about chaos make everyone else be at the receiving end and both sides end up suffering,” he says and remembers vividly how many Muslims and Christians protected each other during such conflicts.

This is why Mamman is currently proactive in his approach to rekindling his relationship with ‘lost’ Muslim friends and neighbours, thanks to social media. “I remember how we used to play football together as boys. There was no discrimination,” he tells HumAngle.

Government efforts

Way back in 1983, Christopher Bature, 75, moved his then young family to Unguwan Sunday. His Muslim neighbours included Usman the bricklayer, Ja’afaru who worked with the United Bank for Africa (UBA), and Baba Auwalu, the tailor, who now lives in Rigasa. These are people he cannot forget, he says.

“Not everyone left after the 2000 conflict. Some sold their houses in the same way Christians did in Kaduna North. Yet, Baba Auwalu’s son still lives in the community today, and recently the father asked for my phone number from his son,” Bature says.

He adds that some Christians do not love each other and that everyone is on his own. “It’s easier to be close to a Muslim than a Christian who isn’t your tribe. If something happens to you the Muslim will always come.”

Bature further says that the government of the day is also not ready to bring the two religions together. “El-Rufai shows clearly that he prefers the Muslims to the Christians. The Governor, Deputy Governor, and Speaker are all Muslims. We are encouraged to stay apart. So, the government is not helping us to come together.”

The Kaduna State Government has, however, made efforts to guide the conduct of religious preaching, which it believes sometimes triggers conflicts between members of the two religions. Also, non-governmental organisations such as Interfaith Mediation Centre (IMC) have made some attempts to bridge the gap between the two faiths.

Nevertheless, Ibrahim Abubakar, Imam of Acro Mosque at Hayin Banki, points an accusing finger at politicians. He stresses that they are responsible for the city’s division.

“Where I lived in Hayin Banki, you would find Muslims and non-Muslims living in the same house or next to each other. Even though we now live in peace with Christians in my neighbourhood, there are not as many as they used to be,” he says, adding that “God knows why we all have our different beliefs. We were happier together.”

But Abubakar believes things will change if politicians will be sincere and help solve the problem.

“Politicians use youths to fuel crises and then when they get into power, they leave them to their devices. Instead of enrolling them in school, they ignore them. And the youths don’t know how to make a living any other way.

“Everything you see happening, from Katsina, Zamfara to Sokoto is caused by politicians.”

Adamu Yusuf, who owns a laundry shop at Hayin Banki, throws his weight behind the Imam’s argument. Having lived in Kaduna North for about forty years, he notes that “everything started from our leaders. They know that when they are able to divide Muslims and Christians, they are able to rule.”

He recalls when fuel price was increased during Goodluck Jonathan’s era “and the country rose up against it with one voice. They don’t like that because it shows we can be strong when we unite. At the end of the day, this division affects us the masses the most.”

Yusuf rents a house owned by a Christian in Hayin Banki. Some of the occupants are Christians too. “Yet we live in peace,” he points out.

Zakariah Makama Takar, Pastor of Bege Baptist Church, Unguwan Barde, adds that peace can only be achieved if the people themselves embrace it and leaders are honest.

“Everything that’s happening is instigated by our leaders because it’s the leaders who cause conflict among the masses. If leaders can desist from pitting the people against each other, there will be peace,” he says.

Takar came to Kaduna in 1982, immediately after he finished his primary school education. He later pastored a church in Tudun Nupawa for eight years. He says there used to be understanding and togetherness in the community though Christians were a minority, but such circumstances can hardly be replicated today.

“If you live where there aren’t many Christians, you live with uncertainty,” he explains. “Back in the day, I could stay till 10 p.m. in Rigasa without fear. But now I can’t be in Tudun Wada or Rigasa around that time.”

Hindering progress

Aliyu Abdulhameed, 50, sews caps for a living at Hayin Banki, a community he has lived in since the early ‘90s.

Back then, some Christians, in a show of solidarity, even performed ablution and prayed with their fellow Muslims, he tells HumAngle. “Sometimes they even became Muslims. It’s peaceful living that brings about such development.

“Later on, ethnicity led to pointing fingers where Muslims would say ‘that person is an infidel’ and so they would have nothing to do with him.”

There were many Muslims Abdulhameed knew who related with Christians and for this reason he too got close to them. “Some, like Friday, have left Hayin Banki, but when we meet, we relate well.

“If I had my way, things would go back to the way they were and religious intolerance, discrimination and killings would stop. I want Allah to bring back that peaceful living we once had because a place cannot prosper until people who have differences live together, be they Muslims, Christians or even those who don’t have a religion. This brings about development because they will sell different things in the marketplace that another will benefit from. But the lack of this brings about unnecessary conflict.”

Then he adds that sometimes it is conflict with the government of the day that is turned into a religious issue.

“The mix [Christians and Muslims] led to improvement in terms of education, especially for the Muslims. Some of the Muslims say they miss it here. Some even moved back to a predominantly Christian area,” he says. “Both sides have disadvantages, whether as a Christian or Muslim dominated settlement.”

https://youtu.be/_xCiZiIcGtM

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter

Hmmm! What a read.

I am overwhelmed by this information right now. This is brilliant.