The Discreet Lives Of Women Living With HIV In Nigerian IDP Camps

To be infected with HIV as a displaced person in Northeast Nigeria is to find yourself in hot water. No thanks to the Boko Haram insurgency, essential health services are unavailable in the rural communities. Funding is not enough to accommodate the special needs of people living with the virus. And, many would rather die than share their status with fellow IDPs because of severe stigmatisation.

Hajiya*, 30, was out of town when Boko Haram militants attacked Bama in 2014. By the time she returned, her husband, Alhaji Mali, had been killed and her children, four-year-old Hauwa and seven-year-old Sadiq, had been abducted and taken to the group’s forest hideout. Knowing she could not live with both tragedies, she tracked down the terrorists, surrendered herself, and spent the following two years and some months in their camp, hoping to escape eventually with her son and daughter.

Within those few, dreary years, Hajiya was forcefully married thrice to different Boko Haram fighters. She now believes this must be how she came to be infected with HIV, a sexually transmissible virus that attacks a person’s immune system, making them vulnerable to a host of diseases.

Since the infection currently has no effective cure, people who live with HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) depend on a life-long treatment known as antiretroviral therapy to live healthy lives. The drugs, which reduce the viral blood in a person’s blood, have to be taken frequently and regularly, despite having a number of side effects.

A lot of progress has been made in curtailing the spread of the virus since the first case was locally detected in 1985. Nevertheless, as of 2019, about 1.8 million people in Nigeria were estimated to have the infection, placing it as the country with the world’s second-largest HIV epidemic. But Nigeria also has a huge problem of discrimination. About half of adults interviewed in 2018 said they would not buy fresh vegetables from a vendor if they knew he or she was HIV positive. They also do not believe children living with HIV should go to the same schools as those without the infection.

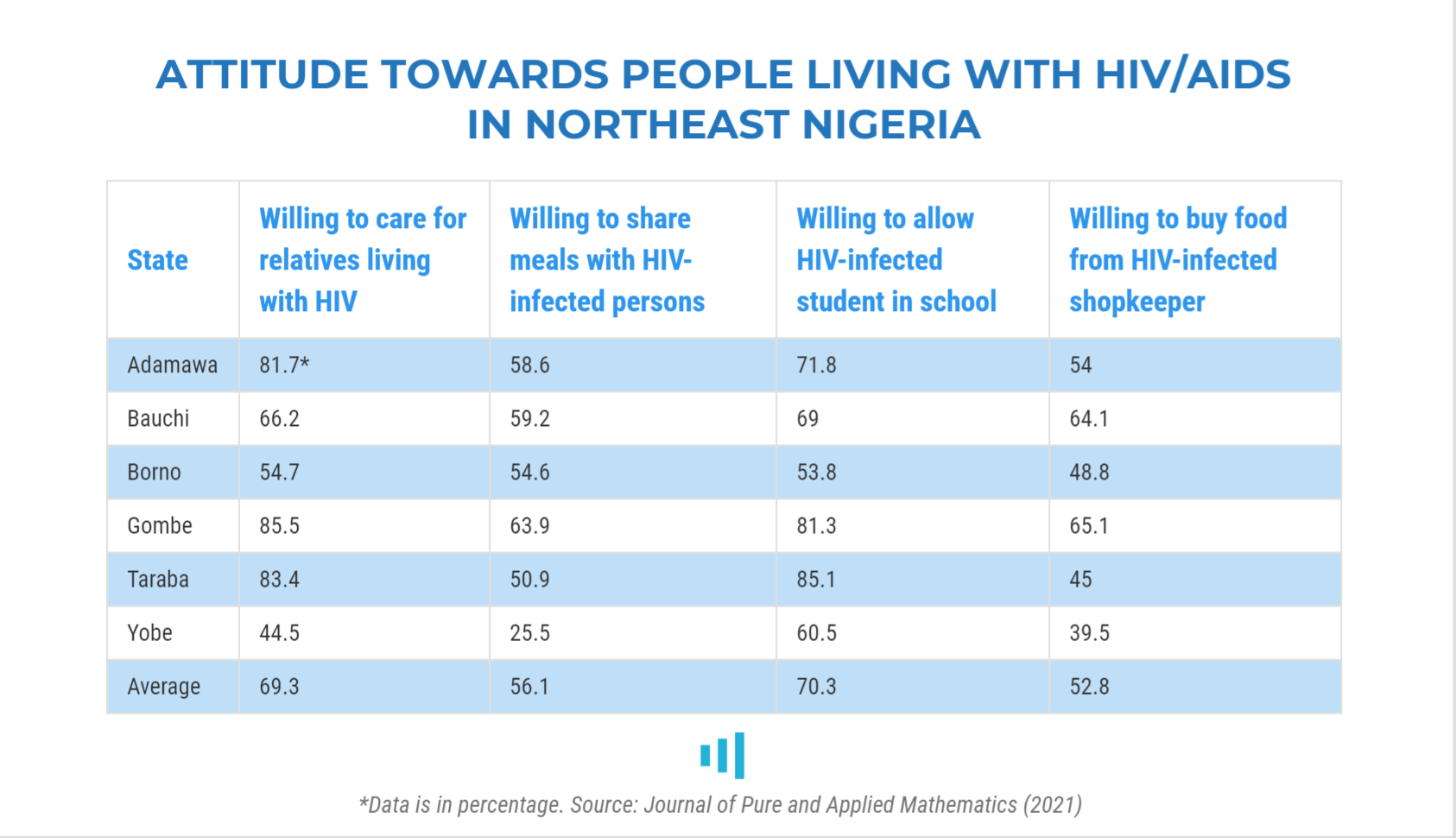

HIV-related stigma, a 2021 study showed, is equally pronounced in northeast Nigeria, especially Yobe and Borno states. In Borno, only 55 per cent of the respondents were willing to care for relatives living with HIV and could share food with infected persons, and only 49 per cent were willing to buy food from shopkeepers living with HIV.

This problem is exemplified in Hajiya’s story as well as the experiences of other women displaced by the Boko Haram insurgency, which has lingered for over 11 years.

Her husband’s murder and her children’s abduction were not random. Four of her late spouse’s brothers were Boko Haram members and led the kidnapping. Eight other children from the community were also abducted, the oldest being a 10-year-old boy and the child of Hajiya’s in-law. They were lured with the promise of getting gifts of Bobo, a popular flavoured milk drink, if they cooperated.

Her husband had taken a different path from his siblings. Rather than join the terror group, he worked for a vigilante unit, led by famous crime-fighter Ali Kwara. “When they came to Bama, they told him, ‘You are a disbeliever killing innocent Boko Haram; we have to kill you.’ And so they slit his throat,” Hajiya narrates in a low-pitched tone, her left hand drawing imaginary patterns in the mat before her.

How did Alhaji Mali’s brothers end up at the frontlines of Boko Haram’s war? According to Hajiya, they were studying at a Qur’anic school in Banki, Borno State, when the town was captured by Boko Haram. Three of them then followed the invaders to their hideout in Sambisa forest and took up arms. A fourth brother joined later. She adds that three of the siblings are now late.

Recalling her time in Boko Haram captivity, Hajiya says there was suffering but not as much as some people faced. One of the greatest sources of anguish for her was that she was forced to tie knots with members of the same group that killed her husband not long after his death.

“I was married three times. One cannot stay there without getting married,” she says.

She had come up with different excuses. First, she said she wanted to observe the ‘iddah, a waiting period during which Muslim women who had divorced or lost their husbands secluded themselves and refrained from remarrying. It lasts for four months and 10 days and, if the widow is pregnant, until she gives birth. But her protest was rejected because her “husband died an infidel and the waiting period does not apply.” She also complained that she was ill, but this only bought her a short respite.

“After some days, they brought someone and said I should marry him. I can then go to him for treatment,” she recalls the time she finally had to resign to fate.

“My new husband’s house was very strict and I couldn’t move around. I then married another husband and a third. My third husband was lenient. He allowed me to move and even took me to see his relatives in Basa, near Fulka. It was the first time I saw the main road. He later went to fight at Bita and got killed there.”

Having had the rare chance of visiting the city, she mastered the routes and returned to them as she escaped to Bama with Hauwa and Sadiq.

Tested in detention

Hajiya was arrested in Bama and taken to Giwa barracks, a notorious military detention centre that has mushroomed in Maiduguri, Borno state capital, since the insurgency started.

The conditions of the cells were unpleasant, with inmates constantly falling ill and some breathing their last before having a taste of freedom. One day, a non-governmental organisation visited the facility and requested to conduct general tests for the detainees. After the exercise, the aid workers started giving piles of drugs to a group of at least 10 detainees. But they had no idea what the medicine was for.

“We started complaining that why were we always taking drugs. They told us we were suffering from a disease and needed to take them. We then refused to continue. So, they later came and disclosed that we were HIV positive,” narrates Hajiya, trying not to be distracted by her son who is intermittently raising her chador to have some breast milk.

The announcement persuaded the detainees to retrace their steps and resume their treatment regimen. Hajiya never suspected she could have caught the virus. She was not severely ill and all that concerned her was her detention and the possibility of freedom. When she learnt she was living with HIV, she immediately suspected it must have been through one of her three husbands back in Sambisa.

Sometime in 2017, she was released from Giwa barracks alongside other infected detainees and taken to Umaru Shehu Hospital, also in the capital city of Maiduguri, where they were given new drugs. At the hospital, she complained the drugs were making them dizzy, and the healthcare providers replied that hunger must have contributed to this. But she says the side effects persisted even after she started taking adequate food. So, she stopped.

After spending about three months at one of the displacement camps in Maiduguri, a care provider visited her. Together, they visited the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital (UMTH) to conduct another test, which confirmed her status was still positive. The hospital gave her a new set of less-troubling drugs. Because of movement restrictions at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic last year, she received enough antiretroviral drugs to last six months, and then another batch that would last through four months.

Hot waters

A 2018 report published by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) identifies people living with HIV/AIDs among those disproportionately affected by the crisis in Northeast Nigeria.

Malnutrition and the lack of basic hygiene and health services make it especially difficult to tackle infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDs in displacement camps.

Executive Secretary of the Borno Agency for the Control of HIV/AIDS (BOSACA), Barkindo Saidu, lamented in 2017 that 3,800 new infections were recorded in the state’s IDP camps in the first quarter of that year alone. Across the state, only half of the new cases were receiving HIV medications and counselling.

Because of the insurgency, Saidu noted, two-thirds of the antiretroviral centres in the state had to shut down and only a tiny portion of residents living with HIV could access treatment.

The global non-profit, FHI 360, had reported in 2015 that none of the recognised IDP camps in Borno had antiretroviral refill and comprehensive care services. And only 30 per cent had “some form of HIV testing services” and staff trained in HIV counselling.

The implication is that IDPs in hard-to-reach communities have to travel to safer garrison towns such as Maiduguri to access antiretroviral treatment and those in the garrison towns have to constantly visit health facilities outside their displacement camps to access essential services.

Despite the unique challenges that come with living with the infection, women who spoke to HumAngle say they are not receiving support outside the provision of drugs—not food, not capital. “Even the drugs, I don’t get them easily. Sometimes they would say I did not come on time and I would have to beg before they give me,” says Hajiya, her face briefly creasing into a frown.

She was once told by an official at the hospital that one organisation was planning to render assistance to IDPs living with HIV. She later heard that the support came in the form of a cash donation of N100,000 to start a business, “but we didn’t get any benefit.”

Maryam*, 30, also a displaced woman who lives with HIV, told us she had not received any support outside medication and is not aware of such programmes. This is despite the fact that the drugs sometimes make her feverish and dizzy, especially when she does not have sufficient food.

“I’d like to have enough food so that the drugs will not shake me,” she appeals. “They have a saying that they are supporting us with food and other things but we don’t see anything on the ground.”

She currently shares her monthly food ration worth about N17,000 with her spouse. They eat thrice a day, rice in the morning and maize in the afternoon and evening. But they only manage to get the food allowance to last up to 20 days. They depend on cap-knitting contracts to make up for the vacuum and get money for other needs.

A consultant physician at UMTH who is familiar with the hospital’s HIV programme confirmed that malnutrition affects HIV management.

“In fact, during the early days, in the 80s, there was a provision of nourishment for HIV patients, but those things are not available now because the funding has reduced,” said the doctor who asked not to be named because he was not authorised to speak to the press.

“Malnutrition, especially when it comes to pediatric HIV, is a big issue. It will affect the management of HIV and is a cause of immunosuppression.”

Hajiya did not have a child with any of her husbands inside Sambisa but gave birth to a second son after regaining freedom. He is positive too and so has to take drugs regularly. His father, Muhammad, was a co-detainee at Giwa barracks. He was a member of the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) but was accused of ‘conspiracy’ and thrown in jail. He made it out before Hajiya and when he heard she had been released too, he paid her a visit at the Kofa IDP camp in Borno State.

“When I was told someone had come to see me, I wondered who it could be. Then I saw someone in a CJTF uniform. He greeted me and introduced himself. When I didn’t recognise him, he recalled when we were tested for HIV in Giwa barracks,” she narrates.

Hajiya and Muhammad became friends and started dating, at which time she became pregnant with her third child. She wanted them to get married but Muhammad, she says, kept giving excuses.

“I decided to marry him because we are both positive. If I wanted to marry anyhow, I would have done so since. But I don’t want to cause problems to someone who is negative by infecting him. I still want to marry someone who is positive.”

When she noticed that Muhammad was not at all enthusiastic about getting married, she stopped seeing him.

Undercover patients

Women like Hajiya who got married to terrorists before escaping are often mocked by others at IDP camps and tagged “Boko Haram wives.” But Hajiya has earned their sympathy because they understand she went to Sambisa to rescue her children and appreciate her uncommon courage. She is, however, frightened she might get discriminated against for another reason: her HIV status.

Hajiya’s infection is a closely kept secret. Even her mother is not in the know. One day, she sighted her antiretroviral drugs and asked what they were for. Hajiya replied that she was taking them for a heart problem. The old woman herself has a heart disease and Hajiya fears she would worry too much and become hypertensive if she found out.

Another reason she does not tell people is she is afraid they would compound her trauma through unbearable stigmatisation. She has seen it happen before.

“There was one lady that died of the disease a year ago. When she fell ill, people were not even visiting her because they feared they would be infected,” she recalls.

“We were the only ones who used to visit her and give her food and other things. When she died, she was not buried until after over 30 hours. When her relatives were called, they said there were other relatives closer to her than them. So her close relatives had to come from outside the camp to give her a burial.”

Maryam has had a similar experience. She suspects she got infected through her second husband. She had remarried after her original husband had spent nearly five years in military detention without trial and much hope of his release.

“I was told when I went to the hospital. When I informed him, he said he was also told that his former wife had been sleeping with soldiers. He tested positive as well. He later apologised to me and advised that both of us should go to the hospital and start taking the drugs.”

Like Hajiya, she has been secretive about her status too. “They don’t know and I don’t want them to know,” she asserts. “If people know about those that are infected, they will keep away from them.”

She adds that only her husband, the fixer, and now, I, know she is HIV positive. She would wake up super early so she can take the drugs without raising eyebrows. A great part of her fear is driven by the tragic experiences of victims of stigmatisation that she has heard from fellow IDPs. She cites two examples.

One was a woman who was too shy to collect her drugs because of discrimination at the IDP camp. She eventually became ill and died. Her husband reportedly died six months later.

“Then, there was one mechanic man who died of HIV and people were avoiding interaction with his wife. She had to leave for Bama and started taking her drugs. They don’t want to even sit in one place with them [people living with HIV].”

One consequence of the pervasive stigmatisation, the UMTH consultant physician explained, is that people who test positive for HIV secretly turn to traditional healers for help, thus delaying the start of critical antiretroviral therapy.

He highlighted other challenges too. One, the donor-funding that comes from organisations such as Chemonics International and Global Fund do not address opportunistic infections — that is, diseases that exploit the HIV patient’s weakened immune system. As a result, while patients generally get free antiretroviral drugs, people with such infections have to pay out of pocket for treatment.

Another issue, he added, is the restrictions in movements occasioned by the Boko Haram insurgency. Residents of villages who used to visit Maiduguri for HIV treatment and counselling are no longer able to do so.

“Chemonics has tried to help us by going to the villages to give these drugs, but the insurgency poses a challenge to such efforts,” he said.

Nigeria had established the National Agency for the Control of AIDS (NACA) in 2000 to, among other things, mainstream HIV interventions to all parts of the country. When HumAngle called the agency’s spokesperson, Toyin Aderibigbe, to confirm what they are doing to address the many problems faced by IDPs and others in war-ravaged communities, she asked that enquiries be emailed to her instead.

She has, however, neither acknowledged nor responded to the email, despite reminders.

Displaced women living with HIV feel like they are caught between a rock and a hard place. They cannot be found taking their antiretroviral drugs and may have to relocate to a new environment if, or each time, this happens. But then again, they cannot simply stop taking the drugs. Maryam knows full well what could happen if they did.

She lost a child a few years ago to non-compliance with the treatment regimen. He was only 23 months old when he fell sick and died. She had received drugs on his behalf at UMTH and, when he exhausted them, she did not return for more. When she changed to the State Specialist Hospital, she did not inform the officials her child was positive.

“It is really painful to lose a child,” she says, her soft voice struggling to be heard amid chatter from youngsters frolicking at the building’s entrance. Perhaps, she thinks, he would still be alive today if the environment were safer for people in their shoes. If they did not have to choose between staying alive and being accepted as normal members of the community.

*Names were changed to protect their identities.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter