The Deadly Consequences Of Blasphemy Allegations In Nigeria’s North

The allegations often ignite a fuse that leads to mob justice, leaving a trail of tragic stories — with little or no accountability for perpetrators.

Talle was a person of relentless determination. Despite a lifelong struggle with mental illness, he had built a family in Sade, a small community in the Darazo area of Bauchi state in Nigeria’s North East, becoming the proud father of eight. Every dawn, he would switch on the submersible pump, draw water to a tank, and distribute it to his fellow villagers for a modest fee. His dedication to his small business earned him his nickname, “Mai Ruwa,” a Hausa phrase which translates to “The Water Seller.”

On an otherwise ordinary day in 2021, Talle’s life took a tragic turn. A young girl approached him, pleading for water without payment. Moved by her appeal, he granted her request, not once but twice. When she returned a third time, he adamantly refused. She persisted, invoking the name of God, but Talle stood firm. Desperate, she finally invoked the name of Prophet Muhammad, a plea that allegedly led Talle to make a fateful, blasphemous statement in his frustration.

The girl returned home with her story, setting off a chain of events that would culminate in murder. At first, the rumour of blasphemy seemed insignificant. But within a week, it had reached the ears of everyone in Sade, including the local traditional and religious leaders (ulama). Summoned before them, Talle explained that he had only intended to insult the girl, not the Prophet, and since that was also a sin, he promised to repent.

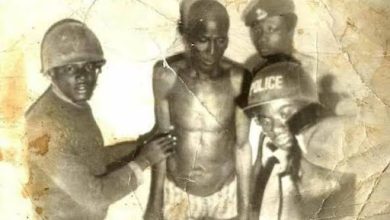

However, the teeming mob outside demanded that Talle be brought to them immediately to face their wrath. The local ulama decided to take Talle to the police for his safety and to face a Sharia Court. As they transferred him, the mob grew increasingly restless, demanding immediate justice and threatening to burn down the police post. They finally overpowered the police and stormed the post, dragging Talle out. Despite the security agents’ attempts to intervene, the mob’s fury was uncontainable. They beat Talle mercilessly and eventually set him ablaze.

“After beating him to a pulp, they contributed money among themselves, bought fuel and burnt him to ashes,” an eyewitness told HumAngle. People were there, and they saw it happening. While a few of them withdrew from the scene, many others participated either by contributing to the fire or by cheering and jeering the mobs. The sounds of “Allahu Akbar” filled the atmosphere.

In the aftermath, “nobody was held responsible,” said Talle’s brother with teary eyes. For him, he didn’t only witness the merciless mob action but also the unforgettable death of a relative he grew up with. “We were circumcised on the same day in the same place,” he recalled.

Since the tragic incident, he has been trying to find a way to fight for his brother. A few rights groups had initially offered to support their legal appeal, but “they didn’t come back.”

Talle’s widow, Inna, now struggling to care for their children, lamented their dire situation since his death. “The children were all dropped out of school,” she said. “And as we are fighting for what to eat, how can we pay for legal services?”

What haunts her most is that virtually everyone in the community knew of Talle’s mental health issues and what his triggers were. Yet, in the heat of the moment, “nobody cared. He was killed by the people who knew him perfectly and who should have testified of his mental health condition.”

In Sharia Law, a person with mental health problems is exempted from responsibility. The concept of “Taklif” in Islamic Jurisprudence stipulates that if a person’s mental health condition renders them incapable of understanding the gravity or consequences of their actions, they may not be held criminally responsible for their actions.

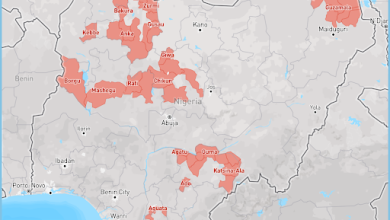

However, the perilous nature of mob justice in northern Nigeria, particularly on the accusations of blasphemy, often leads to death. In conservative states like Sokoto, Bauchi, and Kano, such accusations are often weapons in personal, sectarian or political conflicts. People who participate in similar mob actions rarely ask questions before participating.

Mark Amaza, a Nigerian activist and development worker, captured this issue in a tweet he posted in June 2023 in response to a blasphemy killing in Sokoto. “You want to eliminate someone? Just accuse him of blasphemy against the Holy Prophet. No questions asked by the bloodthirsty mob that emerge suddenly,” he wrote.

Mob violence

Allegations of blasphemy in northern Nigeria often ignite a fuse that leads to mob justice. This grim reality has recurred with unsettling frequency, leaving a trail of tragic stories like that of Talle Mai Ruwa. However, despite the occasional arrests, no perpetrator has faced the full wrath of the law — except for the 1999 incident in Kebbi involving one Abdullahi Umaru, who was lynched by Usman Kaza.

The law is unambiguous regarding the criminality of participating in jungle justice. According to Shettima Danazumi, an Abuja-based lawyer, no one should take the law into their own hands, as “everyone is presumed innocent until found guilty by a court of jurisdiction.”

He emphasised that mob justice is a stark violation of fundamental human rights enshrined in Nigeria’s constitution. Everyone has the right to a fair trial, in which the state attempts to prove the allegations beyond reasonable doubt.

“The whole essence of enshrining the provisions of the fundamental human rights in the constitution is to ensure the protection of basic humanity, to combat the habit of might is right and to enforce the common decency of all human beings,” Danazumi said.

Another lawyer in Kano, Sadik Ibrahim, pointed out that people who participate in mob actions are considered criminals if found guilty. Section 7 of Nigeria’s Criminal Code makes it clear that it is not only those who inflicted the fatal blows that have committed a crime but also those who aided the crime and encouraged others to commit it.

Yet, the harsh truth remains that in cases mirroring that of Talle, the Mai Ruwa, even the few arrested individuals were usually released without proper legal proceedings. In numerous instances, no arrests were made at all. This was the case when a man, identified as Yunusa, was caught in a difficult situation.

In early June 2024, the village of Nasaru in Bauchi state witnessed another lynching over alleged blasphemy. The victim, Yunusa, linked to the highly esoteric Sufi community known as Yan Faira, was brutally killed. Despite a statement from the state police, no participants in the mob action were detained.

The year 2023 saw a similar fate for Usman Buda, a butcher in Sokoto, whose life ended after a heated religious argument in the market led to accusations of blasphemy. The preceding year, Samuel Deborah, a student, was killed after sending an audio message on WhatsApp, which was perceived as blasphemous. Arrests were made, but suspects were released after the police failed to prosecute the case properly.

The pattern goes back many years. In 2016, Bridget Agbahime, a 70-year-old woman, was killed near her shop in the Kofar Wambai area of Kano after an argument led to accusations of insulting Prophet Muhammad. Four arrests followed, but those individuals were later freed.

These incidents paint a distressing picture of a justice system failing to uphold its own laws, where mob violence overrides legal processes and human rights. The impunity fosters a situation of fear, injustice, and potential loss of life to criminals who may likely never be held accountable.

| S/N | Name/Incident | Year | Location | Accusation | Consequence |

| 1 | Abdullahi Umaru | 1999 | Kebbi | Blasphemy against the Prophet Muhammad | Killed |

| 2 | Isioma Daniel | 2002 | Kaduna/Abuja | Blasphemy in a newspaper | 100+ killed |

| 3 | Florence Chukwu | 2006 | Bauchi | Confiscated Qur’an | 20+ Killed |

| 4 | Danish cartoon | 2006 | Various states | Caricature depicting Prophet Muhammad | 16 killed |

| 5 | Christianah Oluwatoyin Oluwasesin | 2007 | Gombe | Defiling Qur’an | Killed |

| 6 | Tudun Wada riot | 2007 | Kano | Drawing Prophet Muhammad | 9 killed |

| 7 | Unnamed Christian woman | 2008 | Bauchi | Desecrating Qur’an | Killed |

| 8 | Sumaila riot | 2008 | Kano | Distributing blasphemous riots | 3 killed |

| 9 | Kano riot | 2008 | Kano | Disparagement of Prophet Muhammad | Shops and vehicles burnt |

| 10 | Unnamed Muslim man | 2008 | Kano | Blasphemy against Prophet Muhammad | Killed |

| 11 | Sara riot | 2009 | Jigawa | Disparagement of Prophet Muhammad | 12 people injured |

| 12 | Bridget Agbahime | 2016 | Kano | Blasphemy against Prophet Muhammad | Killed |

| 13 | Yahaya Sharif | 2020 | Kano | Blasphemous song | Jailed |

| 14 | Omar Farouq (13 years) | 2020 | Kano | Blasphemy | Jailed |

| 15 | Mubarak Bala | 2020 | Kano | Blasphemy on social media | Jailed |

| 16 | Abduljabbar Kabara | 2021 | Kano | Blasphemy | Jailed |

| 17 | Mallam Abba Gezawa | 2021 | Kano | Blasphemy | Jailed |

| 18 | Talle Mai Ruwa | 2021 | Bauchi | Blasphemy | Killed |

| 19 | Deborah Samuel | 2022 | Sokoto | Blasphemy on Whatsapp | Killed |

| 20 | Usman Buda | 2023 | Sokoto | Blasphemy | Killed |

| 21 | Mallam Yunusa | 2024 | Bauchi | Blasphemy | Killed |

Bragging with impunity

The lack of rule of law in Nigeria regarding extrajudicial killings after blasphemy accusations has emboldened participants to openly boast about their crimes. After incidents that generate controversy on social media, some individuals either support or encourage the mob action or openly claim they participated in it.

In 2023, for example, when Deborah Samuel was brutally burned to death, two youths appeared in a viral video. One of them, holding matches, claimed, “I was the one who killed her. I burned her. Look at the matches,” he said. The crowd responded by shouting “Allahu Akbar.”

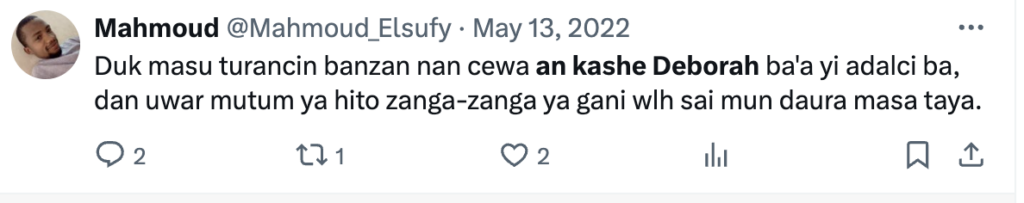

On social media, particularly X/Twitter, several accounts praised the killing. One account posted in Hausa, “Whoever is posting nonsense in English that Deborah was unjustly killed should dare come out and protest, and he’ll see how we’ll ring a tyre on him,” meaning they would burn him to death.

One account posted a video with the caption “An kashe Deborah a banza,” meaning “Deborah was killed and nothing would happen [i.e. there would be no consequences].” Another user quoted it saying, “She was killed for nothing, and her blood was spilt for nothing.”

Justifying what happened to Deborah, some Facebook users claimed they resorted to extrajudicial killings because, even if the case were reported to the police or taken to court, justice would not be served.

“If the youth who killed Deborah were sure that she would be prosecuted, they wouldn’t have taken the law into their own hands,” one user posted.

When the accused killers of Deborah were arrested, some youths in Sokoto protested, demanding their release.

Amnesty International, a human rights advocacy group, has repeatedly criticised the Nigerian government for failing to bring the killers of those accused of blasphemy to justice. This, it said, “create[s] a permissive environment for brutality”.

Forgotten in jail

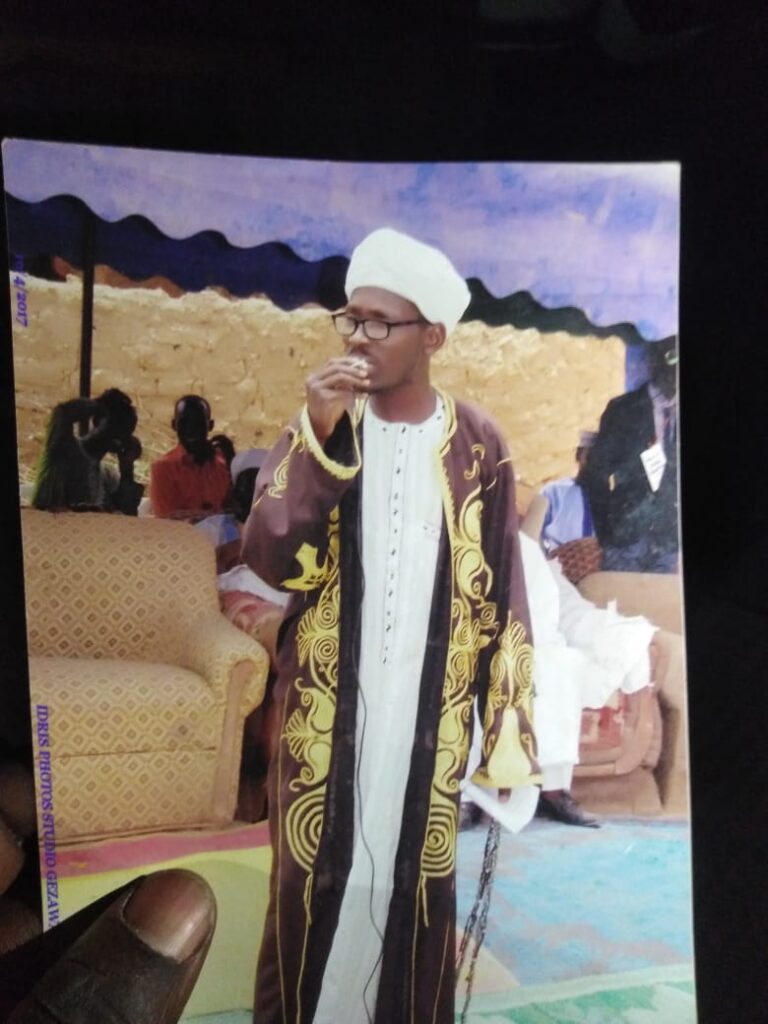

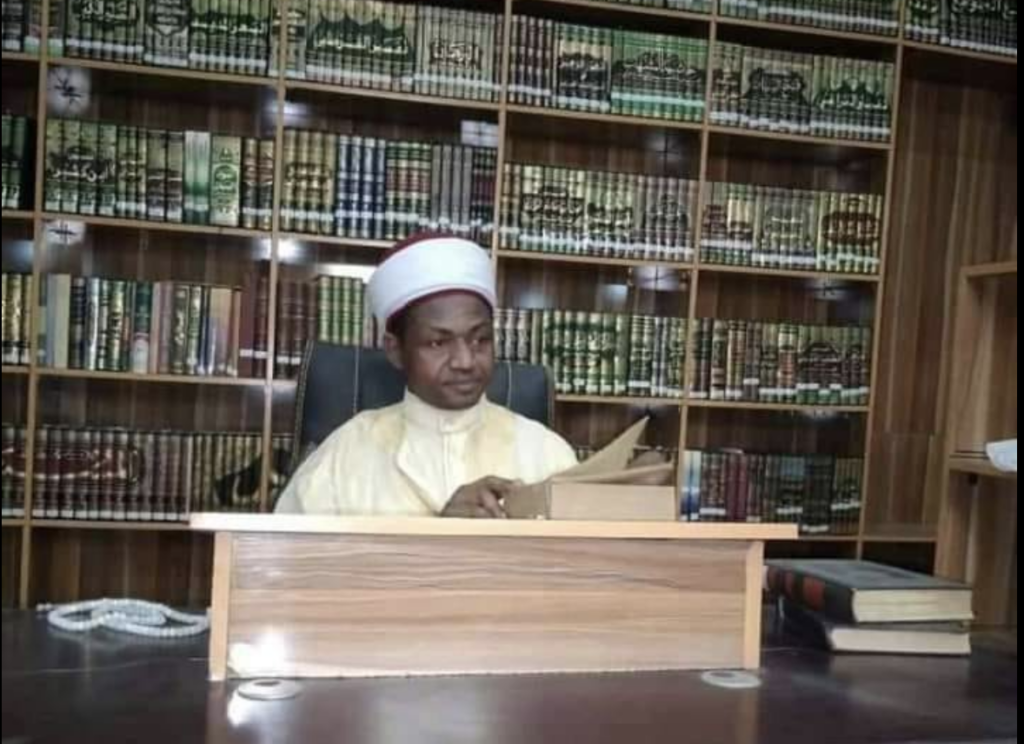

The accusation of blasphemy often leads to swift, brutal justice at the hands of mobs. But for some, the outcome is a life forgotten in overcrowded Nigerian prisons, their alleged transgressions serving as a tool for silencing dissent against local authorities. That was the case of Mallam Abba Gezawa.

Mallam Abba’s journey into adulthood saw him becoming a preacher and leading a local mosque in Gezawa, Kano state. His teachings, critical of conventional Sunni/Salafi views, sparked controversy. As a member of Ashabulkahfi Warraqeem, a group mainly known for opposing Salafism in northern Nigeria, he was at odds with powerful local traditional and religious figures.

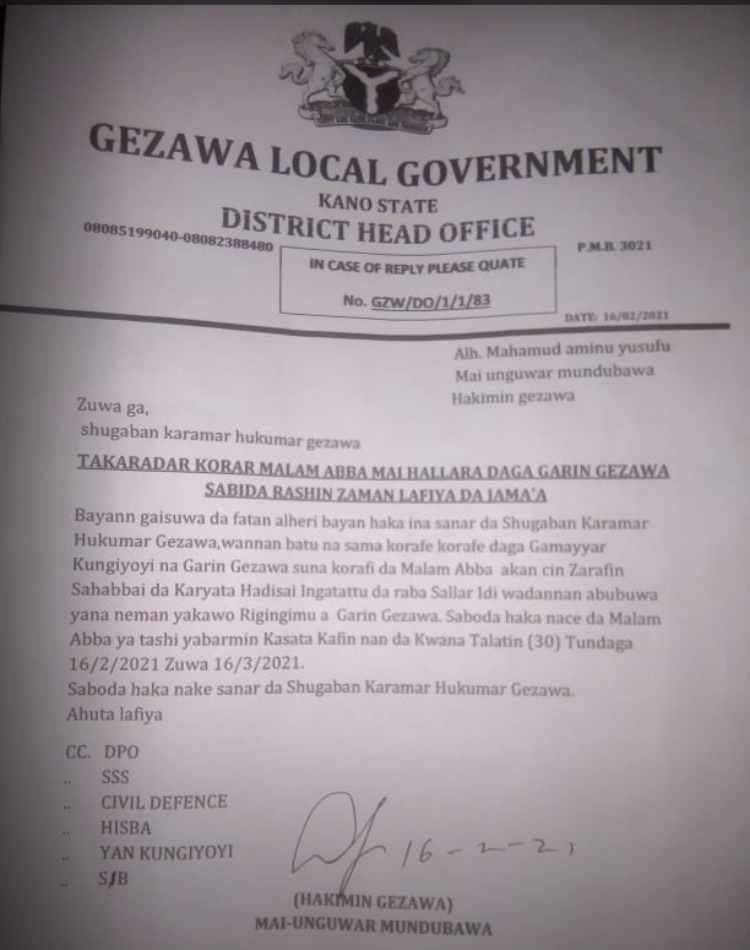

In February 2021, Mallam Abba’s rebuttals against Salafi doctrines led to anonymous complaints to the district head of Gezawa. Responding to that, the district head gave Abba one month to prepare for banishment.

“After complaints against Mallam Abba for insulting the image of the Prophet’s Companions and falsifying his sayings, I have commanded him to leave my land in thirty days,” read part of the letter.

With the intervention of the divisional police officer (DPO) in Gezawa, this unconstitutional banishment was halted. But Mallam Abba’s troubles were far from over. In July 2021, his teacher, Sheikh Abduljabbar Kabara, was charged with blasphemy. Kabara, a fierce critic of Abdullahi Umar Ganduje, former Kano State Governor, had counselled Ganduje to accept defeat during the infamous 2019 re-run after the election was declared inconclusive. His followers believe this political opposition led to Kabara’s arrest.

“From the day he was arrested for his teachings to the time he was taken to prison, we all heard how the former governor was directing everything,” said Muhammad Hafizu, a student of Kabara. “His arrest and detention was purely and obviously politically motivated,” he accused.

Scoring Nigeria 44/100 in the Global Freedom Status, the Freedom House noted that governments in Nigeria embark on “crackdowns against religious groups that have questioned its authority”. It added, “State and local governments have been known to endorse de facto official religions in their territory, placing limits on religious activity.”

On the issue of what he was accused of, Sadi Dahiru explained that “[Kabara] didn’t introduce anything new in Islamic scholarship [that is, commit heresy].” He says, “criticism of sayings falsely attributed to Prophet Muhammad has been in many books. [Kabara] was quoting these sayings to criticise them, but he was accused of creating them.”

During his trial, Kabara insisted he was refuting, not endorsing, these sayings. “Instead of responding to my criticisms, my detractors are attributing to me what I was against,” he said during the trial. Despite his defence, an Upper Sharia Court in Kano sentenced him to death by hanging, a verdict he has appealed.

Following Kabara’s arrest, mob actions targeted his followers. Schools and mosques linked to him were attacked. During this period, Mallam Abba was arrested in Gezawa and also accused of blasphemy. He was taken to court in Kano and left in a correctional centre awaiting trial. He has since languished in detention without a proper trial.

“He has been in detention all this time without knowing his fate,” said his son, Mallam Sayyadi Abba. Although his students and relatives care for his family, it is not the same as having him at home.

While some remain imprisoned, others have been fortunate to escape. Dr Idris Abdulaziz, a Salafi preacher in Bauchi, faced a similar fate. A dispute with the governor led to his arrest in 2023 after a controversial remark on the figure of Prophet Muhammad sparked outrage on social media, resulting in blasphemy charges by the state.

Initially denied bail, Abdulaziz later fled, fearing for his safety. “I realised I was being targeted by the governor because I didn’t support his reelection bid,” he told HumAngle. “He wanted to use the opportunity brought by my enemies against me.” After a month in hiding, he was reconciled with the governor through Nigeria’s National Security Adviser, Mallam Nuhu Ribadu, and returned home.

“It would have been a different story,” Abdulaziz said from his home in Dutsen Tanshi, Bauchi, reflecting on the dangerous circumstances he narrowly escaped.

Hindering free speech

The question of blasphemy versus freedom of speech is a legal and moral labyrinth in Nigeria. The 1999 Constitution enshrines freedom of speech in Section 39, but this right is bounded by limitations for “public order,” “public morality,” and “national security.”

Nigeria’s Criminal Law and Penal Code, applicable in the northern region, criminalise blasphemy with penalties ranging from fines to imprisonment. Under Sharia Law, which is enforced in some northern states, blasphemy can result in capital punishment.

However, some Islamic thinkers and scholars have criticised the blasphemy killing, saying it was never mentioned in the Qur’an nor practised by the Prophet Muhammad himself. In his book, “Freedom of Belief in Islam” (Hurriyyatil I’itiqad Fil Islam), Dr Adnan Ibrahim emphasised that Islam has given full freedom of thought and criticism to anybody.

Critics argue that Nigeria’s definition of blasphemy itself is vague, allowing for widespread abuse. What might be seen as legitimate criticism of religious views or free speech is often misinterpreted as blasphemy, leading to violence and human rights abuses, particularly against religious minorities.

The Faira community, known for its highly esoteric religious views and considered an outcast within the wider Muslim communities, has been a frequent target. In 2015, nine members were sentenced to death on blasphemy charges in Kano. Similarly, a teenager named Yahya Sharif faced a death sentence and had his house destroyed following allegations of blasphemy.

Those who change their faith, especially atheists, also find themselves vulnerable. In 2020, Mubarak Bala, the head of the Humanist Association of Nigeria, was sentenced to 24 years in prison for blasphemy. His term was reduced to five years following an appeal in May 2024.

“The Qur’an is full of verses narrating how disbelievers insulted Prophet Muhammad, but no verse said they should be killed for that,” Dr Ibrahim said in one of his Friday sermons. “The arguments for blasphemy killings were only brought up later in the history of Islam to silence dissents and to vanquish religious minorities.”

Meanwhile, Talle’s widow is currently struggling in Sade, hoping help would come from anywhere so that her husband’s killers will finally face justice.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter