The Dark Reality Of Corruption, Lack Of Accountability Among Humanitarian Orgs In Africa

NGOs are expected to conduct their operations in a neutral way, with a focus on alleviating suffering and restoring the normal functioning of communities. But then corruption rears its head.

In the humanitarian sector, accountability is a word bandied about frequently. It is also one of the most agreed-upon principles among NGOs, with numerous codes of conduct and accountability frameworks incorporated into many organisations’ activities and processes.

However, as with any industry, there are organisations that appear to struggle with remaining accountable not just to their donors but to the communities they claim to serve. Recent events have raised questions about accountability standards among these organisations and how they conduct their work.

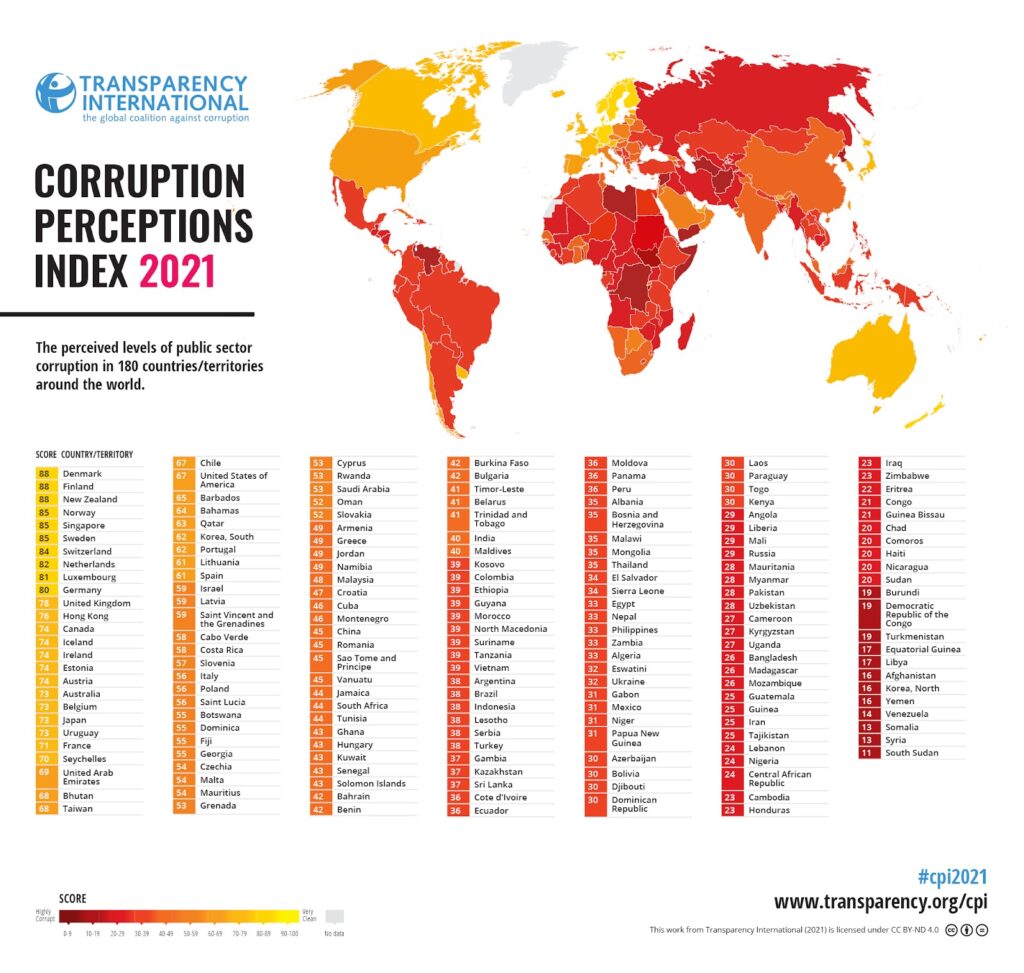

Africa has had an enduring battle with a lack of accountability. The corruption perceptions index shows that 11 out of the 20 worst-performing countries are on the continent.

“80 per cent of countries across the region [Sub-Saharan Africa] have stagnated in the last 10 years,” says Transparency International. “One of the biggest threats to progress is grand corruption – systemic corruption involving high-level public officials and vast sums of money, often accompanied by gross human rights violations. And yet impunity has been the norm, rather than the exception.”

But it is not only the public sector or businesses that are affected. Humanitarian organisations, which are expected to be strongholds of decency, are often rocked by accountability scandals too.

According to the 2019 Global Corruption Barometer Africa report, one in five people in Africa think most or all NGO officials are involved in corruption. That perception is especially bad in places like Cameroon, Gabon, Malawi, Nigeria, and South Africa.

Corruption in the sector can manifest in different ways: paying bribes for services or access, sexual exploitation, collusion, favouritism in the award of contracts and employment offers, fund mismanagement and embezzlement, delayed payments to contractors, and so on.

It is difficult to tell the true extent of this problem because of the lack of data. When they do investigate suspicions and allegations, humanitarian organisations hardly share their findings. And existing studies mostly assess how people perceive corruption levels rather than actually quantify them.

There are, however, many examples across the continent pointing to just how widespread the mess is.

Investigations by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) between 2015 and 2017 found that millions of dollars were lost to Ebola-related humanitarian operations in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. The organisation lost about $2.1 million to collusion between its staff and employees of a Sierra Leonean bank, $1.2 million to fake billing by a customs clearance agency in Guinea, $2.7 million to inflated prices of relief items and other irregularities in Liberia, and so on.

The Ebola outbreak across different countries had inspired an influx of funding and so created a bigger opportunity for corruption. The response in the Democratic Republic of Congo was fraught with fraud too. Rent prices were inflated, kickbacks were given for lucrative jobs, funds were diverted, and suspicious payments were made to security personnel. It became known as the ‘Ebola business’.

“I’ve never seen as much embezzlement and money inadequately allocated as I’ve seen in this epidemic,” Ebola researcher Gary Kobinger told The New Humanitarian in 2020.

Factors Contributing to a Lack of Accountability in Humanitarian Organisations

There are various factors that can contribute to a lack of accountability among humanitarian organisations in Africa.

One is insufficient oversight and monitoring of humanitarian operations. Humanitarian organisations are supposed to be accountable to the people they serve: affected populations and host communities. However, in many cases, these organisations do not receive any feedback from communities that they serve. Moreover, humanitarian organisations often lack the capacity or resources to monitor their own operations, which can result in erroneous conclusions and recommendations.

Lack of political will to fully engage with humanitarian organisations: Many African governments have acknowledged the importance of humanitarian assistance and are committed to ensuring that affected populations receive the assistance they need. However, some governments lack political will to fully engage with humanitarian organisations, which can result in a lack of accountability.

Aside from the Ebola programmes, widespread corruption is well documented in the DRC. One 2020 survey found that sexual favours and offering jobs in exchange for sex were common — often without consequence. Also, local NGOs and contractors usually paid kickbacks of between 10 and 30 per cent of grant or contract sums to international aid groups, including UN agencies. Organisations refrained from complaining because they were afraid of being blacklisted by the aid community.

“The end result of these pressures was described as reducing impact of aid for aid recipients, adding pressures to a difficult local market, and increasing food insecurity,” the report concluded.

Such practices also lead to a lack of trust as local communities tend to “perceive humanitarian aid as corrupt and driven by external agendas”. They encourage a culture where community leaders and other stakeholders expect to be bribed to cooperate. They lead to the fabrication or exaggeration of data. They also promote the implementation of low-impact programmes that benefit the aid organisation more than the target beneficiaries.

“Tackling corruption better matters because [it] limits the scarce amount of aid reaching people who desperately need it,” aid worker and researcher Paul Harvey writes. “Any aid that is corruptly diverted is not reaching the vulnerable people who need it most.”

The idea for the 2020 Congo survey came after business owners were caught trying to bribe a Mercy Corps official with bags of cash two years earlier. Following the organisation’s investigation, one senior official estimated that aid agencies may have lost up to $6 million to a rapid response programme within two years.

“When a conflict or natural disaster occurred, aid groups would receive reports from local community leaders that exaggerated the number of people who had fled their homes. Business people would then pay kickbacks to corrupt aid workers to register hundreds of additional people for cash support who were not actually displaced. The merchants would then receive the aid payments and share with the local leaders,” The New Humanitarian explained in a 2020 report.

The lack of accountability in humanitarian organisations is a serious problem that can have negative implications for affected populations, host governments, donors, and the reputation of the humanitarian sector as a whole. It can also negatively affect the ability of humanitarian organisations to effectively deliver assistance.

In order to address this issue, it is important for humanitarian organisations to be more accountable and transparent in their operations. This can be done by ensuring that NGO audits are conducted on a regular basis and that proper accounting records are kept. Additionally, NGOs should make use of technology to improve transparency and accountability, such as by using online platforms to track grants and donations.

Transparency International recommends that all stakeholders speak more openly about the problem of corruption. Host governments should develop aid-specific anti-corruption laws and monitor humanitarian programmes. Donor governments should “increase funding cycles to decrease pressure to spend quickly” and create incentives for reporting corruption risks. Finally, humanitarian organisations should have anti-corruption and whistleblower policies, strengthen risk management for larger operations, and encourage shared learning on good accountability practices.

Harvey, who is the founder of Humanitarian Outcomes and a cash programming expert, believes the challenge of corruption does not persist due to a lack of policy or risk management processes.

Rather, he says, “it seems that there are strong organisational and institutional incentives within the current system making it difficult to more effectively tackle corruption.”

He recommends more rigorous, independent, and regular monitoring of humanitarian action. Research is also needed to better understand the scope of the problem and the best ways to solve it.

“Without this sort of system-wide action, trust will remain in short supply. Donors won’t trust local governments or NGOs, people won’t trust aid agencies and western public support for humanitarian aid will be undermined.”

Note: Parts of this article — including the headline, (most of the) sub-headline and dropdown details — were written by Artificial Intelligence. HumAngle fed the prompt, ‘Corruption and lack of accountability among humanitarian organisations in Africa’, into Writesonic and Simplified and got these results. The results were then fact-checked, compiled and edited by a HumAngle journalist.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter