The Buni Yadi Tragedy: Surviving

Mohammed was one of the few boys who survived the Buni Yadi massacre of 2014. He was shot in the neck, but he survived. He still bears the scars both mentally and physically.

Slowly, as he went row by row shooting the boys, the man made his way to the last row, where Mohammed was lying face first. Completely terrified now, Mohammed pretended to be dead in order not to be shot. The man yelled at him, asking to know his name, but he kept up his act.

The man said, “if you don’t talk now, I will shoot you.” Still, he remained silent.

He cocked his gun and made to shoot, and this was when Mohammad began to cry and beg to be spared. Infuriated, the man shot him in the neck, then shot one of his palms. By some sort of magic, luck, or grace, the bullet merely grazed his neck, piercing him slightly before proceeding to penetrate his hand. The world began to blur as he bled more than he had ever done in his life, more than he thought himself capable of. Things dimmed, then brightened, then dimmed until he knew only nothingness. He expected to die.

—–

In that youthful defying way that teenage boys are known for, Mohammed and his friends had decided they would sneak out of school that evening as they occasionally did, moonlighting as young adults capable of caring for themselves. They were students at the Federal Government College, Buni Yadi, northeast Nigeria, and because it was a boarding school, they were typically not allowed to leave the school premises. Still, they did.

They went inside the town and hung around, chattering about school and girls and their forthcoming examinations. They had just resumed school from the mid-term break and were looking forward to resuming classes the next day. Even though the security atmosphere in the town had been generally tense in the previous weeks, they found themselves unable to stay within the confines of school. There had been increased attacks in the neighbouring villages by the Boko Haram terror group. And because the school was a natural target, there had even been appeals from some of the teachers that the school be shut down temporarily.

Mohammed and his friends bought some roadside food to feast on that night. On their way back to the school, as darkness began to fall, they noticed a man walking behind them a little distance away. They briefly discussed among themselves the possibility that he might be following them, then quickly agreed that it seemed unlikely. To confirm, they slowed their walk and slowly stopped, leaning on a wall, trying to see if the man would stop as well or keep walking. The man went right past them.

But even that was suspicious because they were on a path that led only to the school. Did that mean the man was heading to the school as well? Why was he heading to the school? They did not recognise the face as a student’s or even a staff’s. Brazenly, they braced up, caught up with the man, and asked him where he was going.

He said he was going to the school as he was a student there himself. They told him immediately that he was lying. They were students too, they said, and if he were truly one, they would have recognised him. And then he said he was residing in the staff quarters. Again, they told him he was lying.

“There was no way he was a student at our school. We would have known him, or at least his face would have been familiar, but it wasn’t. Even students or children who stayed in the staff quarters with their parents, we knew them and were familiar with their faces. So it was not possible that we would see anyone living or schooling in the school and not recognise them.”

In the end, as they had no concrete proof, they let him go and then went inside the school. Perhaps, if they had listened more to their instincts, they might have survived what was to come.

That evening, Mohammed Ibrahim sat chatting with his friends in the hostel far into the night. One by one, they each started to fall asleep. Soon, the entire hall went quiet, and that was when Mohammed remembered he had some roadside food from his evening walk with his friends.

“Is anyone awake?” he asked, in a tone that was loud enough for anyone awake to hear but not loud enough to wake them up. One boy said he was awake. “Come,” Mohammed said. “Let’s feast on this food.” As they ate, chatting, one boy from the senior secondary section joined them, and they ate together and chatted. Soon, they were done, and the senior boy left for his hall.

Shortly after that, at around 11:00 pm, Mohammed started to hear what sounded like gunshots. He immediately thought of the strange man who had trailed them that evening.

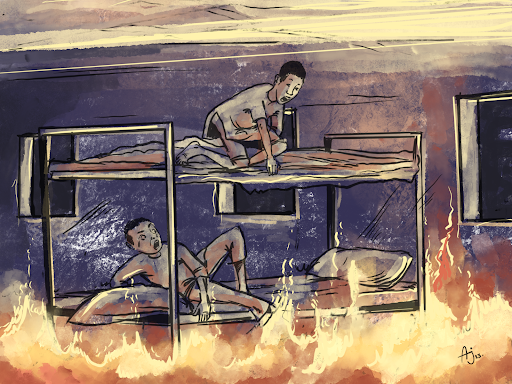

The gunshots came again, louder, in rapid succession, and Mohammed knew that, finally, the day had come. By now, all the boys in the hall had woken up and were in a state of full panic. Being the eldest, he coordinated them all and asked them to lie flat on their bellies to avoid being hit by the bullets flying everywhere.

A boy, perhaps 14 or 15, panicked, looked around and, realising the attackers were coming nearer, hopped on the nearest window, attempting to scale over. Unknown to him, some of the assailants were positioned outside. One of them shot him in the chest, and the boy fell right back into the hall, his chest exploding, dead. He fell right by Mohammed’s feet. Mohammed stood there, completely dazed, staring at the first dead body he ever saw. A boy he had known for years.

He is not entirely sure how, but he found the presence of mind to walk away and coordinate others to lie flat on their bellies. There were some boys who, out of panic, headed for the door but were gunned down. When he was sure everyone had complied, he did the same.

“It was as if we were being robbed. We all just lay down flat. I was the oldest, so I was the one who coordinated everyone else. It was very scary. You could hardly even see where you were going because there had been a blackout. No electricity.”

A man wielding a gun stepped into the hall then. He started going row by row, shooting the boys haphazardly. There was a boy who whimpered, cried, and begged not to be killed, but this seemed to infuriate the man, because he turned around, used his leg to kick the boy in a way that made him roll back on his head, then shot him in the chest.

The man came with a torch because there was no electricity in the school. Everywhere was dark. A boy ran into the hall then, thinking perhaps that hall was spared. The man shot him in both thighs, then shot one of his hands.

Another little boy began to wail, begging not to be killed. This boy panicked so much that he flung himself at the attacker, holding him tightly, perhaps in an attempt to prevent him from pulling the trigger. The man yelled at him to either get off his body or risk being shot. The boy complied and pulled himself away, then went on his knees, all the while begging to be spared.

More men came into the hall then and took the boy away, asking him to show them where the girls’ hostel was. Mohammed would later learn that the boy lived.

“Some of them wore jumpers. Others weren’t as fully dressed. Some of them were disguised with turbans. Others did not bother to.”

The man began to do something strange. For boys who were far too little, he asked them to strip down to their shorts and took a look at their privates before deciding whether or not to shoot them. Later, Mohammed would learn that the terrorists did that in cases where they were unsure if the boy in question was too young and should therefore be spared. They were inspecting their privates to see if they had pubic hairs.

It did not take long for the terrorist, who was going row by row to shoot the boys, to get to where Mohammed was.

Survival

Hours after, Mohammed came to. The terrorists had left, and now there was only the sound of buildings crumbling, fire still burning, and sometimes the cries of boys who had been injured. He managed to drag himself outside the class and further beyond the building by crawling alongside some of his friends. After what seemed like forever, they made it to a wall. Then they began the tortuous process of trying to scale over.

Mohammed made it to the General Hospital, Buni Yadi, through what he thinks is nothing but grace. He went there because he had an older brother who worked there.

I went to the security man and asked him if he knew Musa, my brother. He said he did. I asked him to please get my brother for me. It was still in the early hours of the day. He went away to fetch him but didn’t come back until hours later when the day had fully broke. My brother told me later that when the security man told him there was a boy outside that was bleeding and only looking for him, he knew immediately that it was me.

As Mohammed lay there, waiting, he continued to bleed. He tried to sleep but could not. First, he lay on a wooden bench and tried to sleep, but it hurt. Then he tried to sit on the bench instead, but even that hurt. He spent the next few hours bleeding, laying down on the bench, then sitting on it.

By the time Musa reached Mohammed, the latter had completely lost his speech because of the injury to his neck. His arm had also swollen up. Musa and his colleagues then began the long, tortuous process of rendering him first aid.

They lacked some of the things they needed at the hospital, but eventually, they found some things with which they then attempted to steady his arm for the time being. Mohammed tried to speak to his brother, but no speech would come out of his throat. At first, some words made it out but were jumbled and not audible. Eventually, it stopped altogether.

One of my friends, Shittu, hid under the ceiling as it happened. Because it was dark, he did not know that they had set fire to the classroom after they were done. It wasn’t until the fire got to his leg that he realised. He fell from the ceiling right into the class. Luckily, he fell into a part that had not caught fire yet. He crawled until he escaped.

One of the things Mohammed found surprising was the complete absence of security personnel on those troubled roads in those days. The checkpoints became deserted, and even the vigilante groups that used to be there were no longer there.

We were also at the end of the town. We were at the very end of the village, far from other buildings. There wasn’t any other building after our school.

At the time Mohammed left home for school, there had also been an attack in his neighbourhood. He thought school would be some sort of sanctuary; he imagined he would be free and safe and only now plagued by the anxiety of what could happen to his family back home. But now the horror was right there by his front door.

By the time it was all over, tens of boys had been killed and many more hospitalised.

It’s been a decade now, and there are days Mohammed can still not believe he survived the events of that day. Sometimes it all replays in his head as though happening all over again.

There is a boy he knows, he says, whose mind never returned to him after that night of the massacre. He sees how very easy it was for it to happen because the boy’s best friend had been shot and killed right in his presence. It was perfectly understandable that he would lose his mind, Mohammed says. He does not know where the boy is these days, but he thinks of him from time to time.

He thinks, too, of the friends he lost that night, and of that first boy who fell at his feet, his chest exploding after he was shot.

It is not easy. To suddenly never see someone you have always seen everyday for years. Not everyone can survive that kind of grief.

He doesn’t think any amount of support or compensation from the state could ease the grief or pain he feels.

He dwells on the only form of support that he says would have mattered; in the days leading up to the attack, if there had been adequate security, if there had been constant surveillance, the massacre would not have happened at all. Then there would have been nothing to recover from in the first place, he says.

The effects of trauma, for him, did not come until much later. In the early days, he was more focused on healing from the injuries. It was not until after he left the hospital that the psychological effects began to tell on him.

He had spent months in the hospital physically recovering, and months after deciding whether or not it was worth it to go back to school.

But he did.

Mohammed is currently a student at a university in northeast Nigeria.

A year from now, he will graduate to become an engineer.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter