It all started 11 years ago, or six, or maybe more recently — depending on what community you are from and how soon they got to you. Before that, you had not grown accustomed to the explosive sound of gunshots and life was generally peaceful. You had been hearing of how they brutally attacked neighbouring villages or Local Government Areas (LGAs) and had hoped the violence would not spread towards where you call home. But it did.

They arrive at night, on motorcycles, from behind the trees and river. They constantly shoot into the air. People who run towards the forest are chased. They hit them with their bikes and gun them down. Sometimes they ask them to lay on the ground, point their assault rifles next to their heads, and open fire.

They enter people’s homes, sometimes having to break down the doors. And then they take what they can, including money, livestock, and other belongings. They seize whatever foodstuff they can lay their hands on and set fire to silos. Sometimes, they ask the residents to catch, slaughter, and cook their chickens. And then they eat while the owners watch. If the residents have tuwo and fura, they will eat and drink those to their fill too.

Uncooperative house owners may lose their lives. Many are, in fact, killed — often the male residents. Some are survived by as many as three to four wives and plenty of children. A lot of the dependants eventually take to alms begging.

My son was the one who ran and informed the villagers to run and hide. When they got to him, they killed him. He had seven children. I won’t ever forget it. He used to be our main provider. Aisha Sani, Tangaran, Anka LGA, Zamfara

The shooting is nonstop. If it is close to the Muslim prayer time and people are still in the mosque, they may visit and kill some of the worshippers. And the terrorists burn down structures, including the community dispensary.

If the plan is to abduct residents, they oftentimes target houses with relatively wealthy occupants. Maybe there is a car parked outside or the building is bigger and finer compared to others or they had received information from residents spying for them. If the heads of the households escape, they abduct their children or loved ones in their place.

The terrorists, described locally as bandits, then proceed to stores, ransack them, and take the available cash. They also loot valuables such as prepaid calling cards and foodstuff. They search people and take their phones and, occasionally, their clothes as well.

These bandits enter all the towns, house by house. If you have even a shirt or trouser that is new, they will take it away. If you prepared food, they will take it and go. Isiaka Abdullahi, Kurawa, Sabon Birni LGA, Sokoto.

Sometimes, the attacks are preceded by a phone call during which the terrorists would warn that, unless they are given millions of naira, they would storm the communities. These calls, in the early days, were dismissed as propaganda by the people.

On occasion, the terrorists attack and leave without taking anything but the lives of innocent people. Policemen, responding to a distress call or on patrol, are killed too — that is if there is any assigned to the community at all. The following morning, empty bullet shells litter the compounds and the streets. You sometimes find buildings scarred by bullet holes.

The attackers come at night, but they do not follow a rigid timetable. Other times, they strike in broad daylight. The attacks are sporadic and unpredictable. If, during the afternoon, there is a cry of ‘approaching bandits’, everyone scampers for safety: children, pregnant women, old people. Schools immediately shut down for the day.

You are not sure whether you will be able to catch some sleep or it will be another night in a long line of tragedies. Even on days when there are no attacks, locals tend to have sleepless nights. This is worsened by the startling gunshots. People go to bed uncertain if they will see the next sunrise.

During an attack, the people call Nigeria’s security agencies for help, but it seldom comes when it is needed. The police may say they are not around town and are in the bush for an operation, or complain about a lack of arms and ammunition. Many hours later, they will show up and start asking questions. Other times, according to victims, the police may be metres away from the community under siege but will refuse to act still.

The uniformed personnel are useless. It is until the deed has been done before they decide to show up and say they want to do something. Yesterday, after the children were captured, a certain DPO came and was asking why he was not woken up. But you would inform him and he wouldn’t show up until it is over. Alhaji Jafaru, Yarkofoji, Bakura LGA, Zamfara

The attack may take place between 8 p.m. and 2 a.m. WAT, lasting as many as six hours. Yet, security personnel will often not intervene.

They rape wives as their husbands helplessly watch and daughters to the chagrin of their fathers. Sometimes, one young terrorist forces himself on a woman and another one records with a mobile phone. Such videos have somehow circulated in the past, some say.

They kill, they sex our women, our children, our girls, in front of the father, in front of the husband. If you talk, they shoot you. And you know it is not every man that can withstand for someone to stay before you and sex your daughter. So, in that process, they get killed.” Mahe Umar, Gatawa, Sabon Birni LGA, Sokoto

Those killed can be as young as teenagers or as old as 70 years. Injured victims are loaded on a bike and rushed to the nearest primary healthcare centre. If their injury is severe, they are transferred to a teaching (or general) hospital at the state capital or in a neighbouring state.

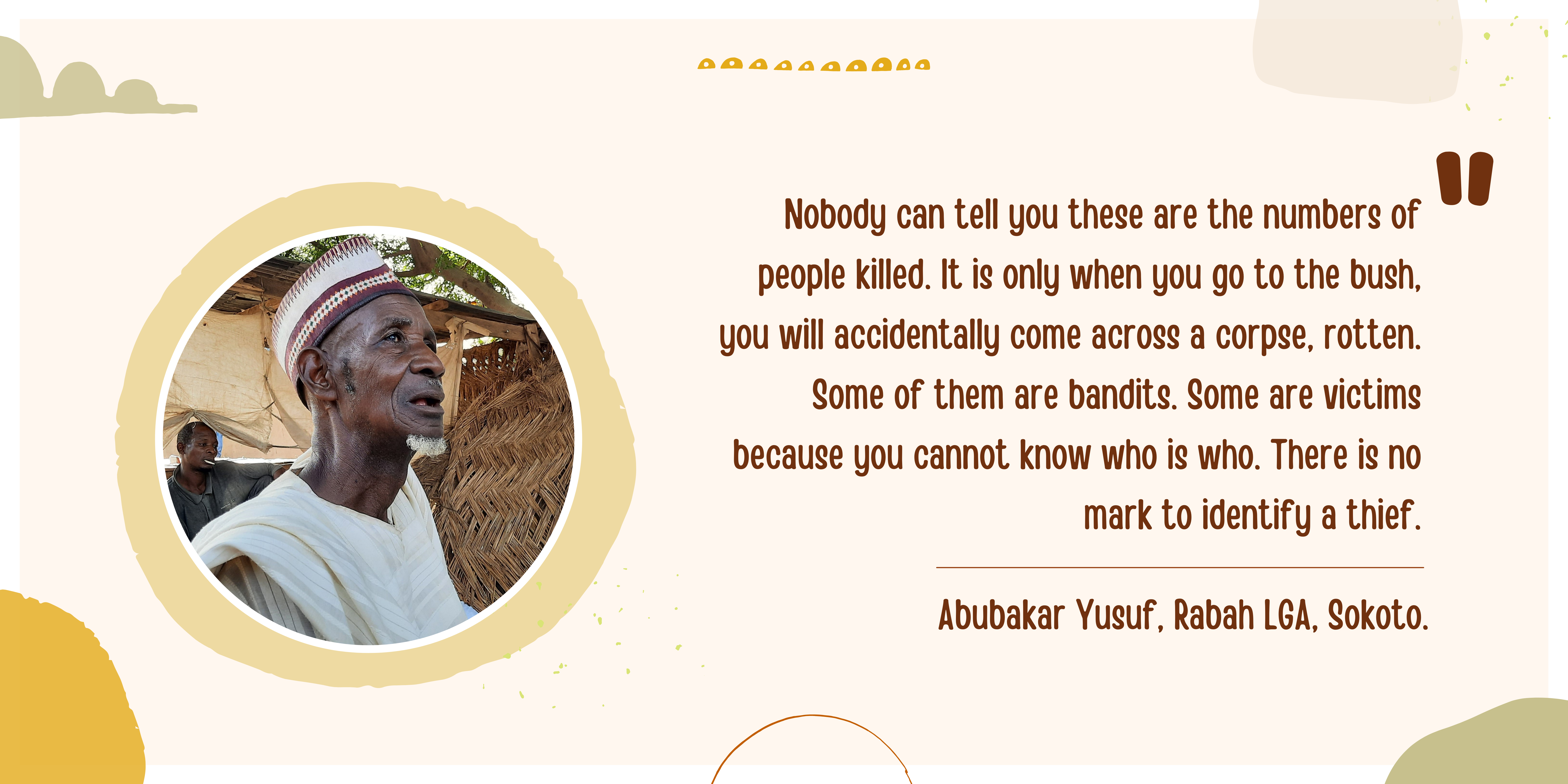

The dead are wrapped in white cloth and buried as soon as possible. Sometimes their pictures are taken to serve as evidence before they are lowered in the grave. Other times, the grieving just want to get the ritual over with and are in no mood for record-keeping.

As the terrorists attack, the people are often scared to protest or hit back, fearing the invaders may return the next day with greater aggression or in greater numbers.

Those in the communities, even if they see bandits on their way going to another community, they don’t talk to them, they don’t stop them, rather they give them water to drink, they give them food to eat. See what they just did to Gangara community. Gangara killed some bandits but, before you know it, a couple of days after, they ganged up and killed almost 20-something people. Mahe Umar, Gatawa, Sabon Birni LGA, Sokoto

Occasionally though, the people summon the courage to fight back, killing some of the invaders. Some communities have vigilante groups, armed with crude guns, knives, flashlights, and juju. When it gets dark, patrolling vigilante members shoot into the air with their Dane guns and flash their lights into the distance, hoping to send a message that they are still awake and perhaps discourage the lurking criminals from invading. They mount roadblocks too in communities closer to the main road.

They start with the remotest villages closest to the forest areas and furthest from highways and other indicators of urban life. Then, as the villages become poorer and unable to meet their demands, as they become more armed and powerful, they shift attention to the towns and cities and local government headquarters — which previously served as safe havens to the village dwellers.

They rustled all our animals, cows, donkeys, and even hens; so we have nothing now. We used to run to the local government headquarters, but even that place is no longer safe. Mustafa Isa, Turba, Isa LGA, Sokoto.

The farms are as unsafe as the communities themselves. As people work on their farmlands, planting beans, cotton, groundnuts, hibiscus, maize, millet, onions, rice, watermelon, and other crops, the terrorists rob and shoot at them. Sometimes they ask the farmers to frisk themselves and surrender their phones, money, and other valuables.

Last week when the first rain of this year fell, they went to the farm and started arresting people. They will just come and tell you to search yourselves and drop whatever you have on the ground and they will take them. Who can go to farm now? Nobody can go to the farm. You can only go when you know your life is secure. If your life is not secure, you are between the devil and the lion. Idris M. Gobir, Sabon Birni LGA, Sokoto.

Men who go into the forest areas to fetch firewood are shot at as well — or slaughtered. Locals naturally wonder how they are supposed to give the terror gangs foodstuff and other valuables if they are prevented from working the only way they know how to earn those valuables. They also fear that without money and other items that can be stolen, the terrorists will simply kill them without hesitation.

Travellers on the road are not spared too. The first ambushed vehicle is shot at to get the road users’ attention and get everyone to stop. They may set the tone by killing someone. It could be that they have a target travelling with money or livestock, based on a tip from informants. It could be they know there are traders on the road with money from sales or money to buy new commodities. Or it could be entirely random. People are abducted so they can later be exchanged for a hefty ransom. The passengers, scared to death, try to make off at first. Some are shot at and killed.

Knowing this, people often travel without their phones and with as little cash as possible. If they hold money, they conceal them in hard-to-discover parts of their body. Those at home too try not to use their phones outdoors, in case an attack takes place and they are forced to part with them. Instead, they leave the devices in their rooms.

There was a time I moved from my village to another village, going to Nasarawa. I was ambushed and attacked. My car was sprayed with bullets all over. Every angle of the car. But by His grace, we were able to escape. Idris M. Gobir, Sabon Birni LGA, Sokoto.

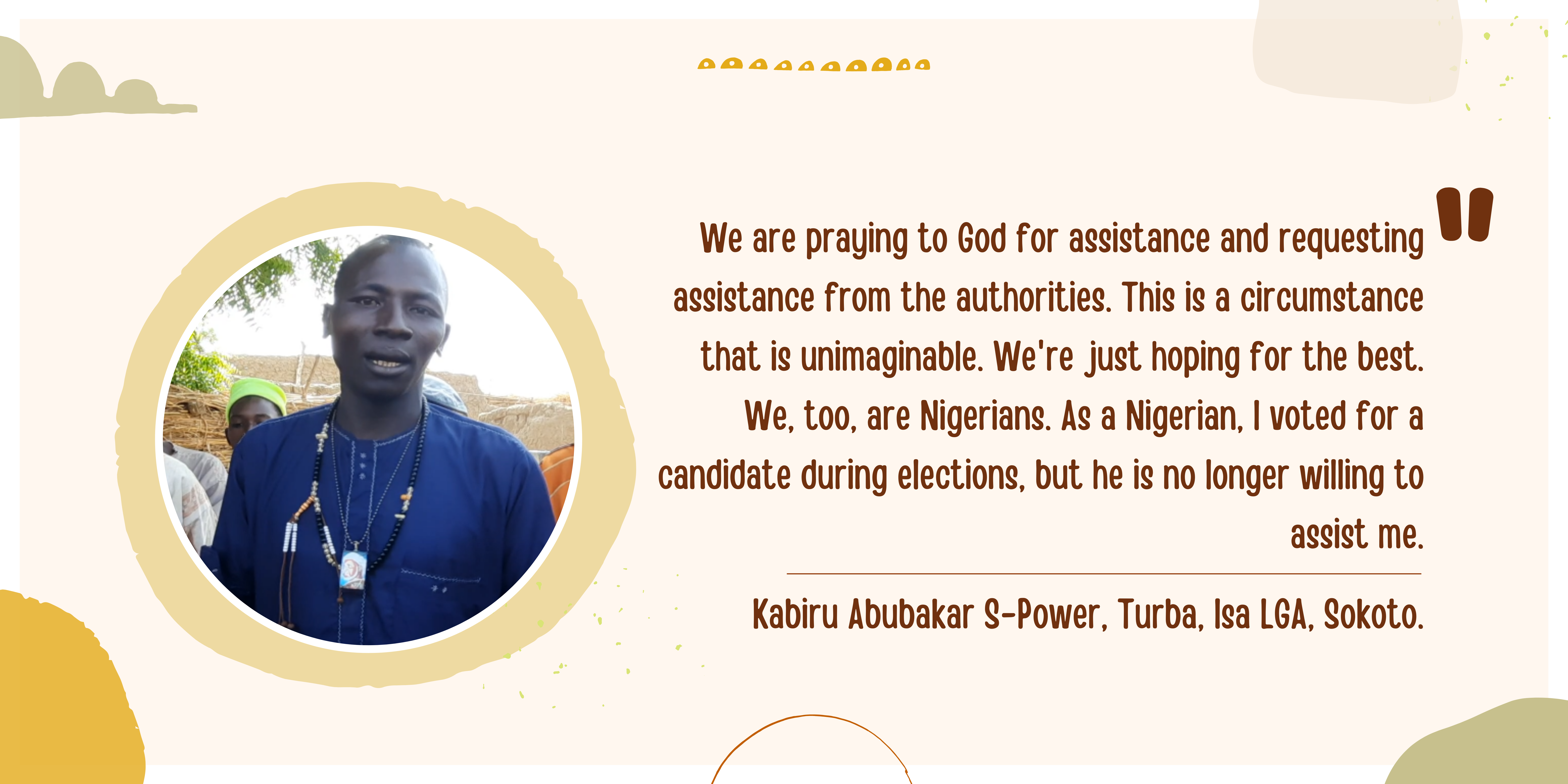

The situation is difficult to define, difficult to put into words that will capture the gravity, and the people are tired of narrating their ordeals without noticeable improvements. In all of this, they feel abandoned by those they elected to represent them in government.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter