Taking Matters Into Their Own Hands

Widespread water and sanitation failures prompt citizen groups to approach the courts.

CAPE TOWN — “It was Dec. 2019 when we approached the court,” said attorney Andreas Peens in Koster, a small town in the Kgetlengrivier municipality in the North West Province of South Africa.

Peens represents the Kgetlengrivier Concerned Citizens, who at the time were asking the Magistrate’s Court to grant them access to the water treatment works. It had been shut down for over a week due to a municipal workers’ strike over salary increases and the concerned citizens wanted to get it running again.

The court granted them access, and the water supply was restored.

This success, Peens said, gave the citizens group courage to address the municipality’s long-standing water and sanitation failures through the judiciary system.

A year later, in Dec. 2020, Peens was back in court, this time in the North West Division High Court, with an urgent application to take custody of both the municipal water treatment works and the sewage works.

Peens explained that raw sewage was being diverted from the sewage works in Koster and the nearby town of Swartruggens, via ditches and pipes, landing straight into the Koster and Elands Rivers. The discharge, in both cases, was upstream of the dams supplying drinking water to the towns.

On Dec. 18, 2020, Judge Samkelo Gura ruled in favour of the concerned citizens, ordering the municipality to stop raw sewage flowing into the rivers and to immediately fix the cause of the problems. Gura also declared the water treatment works at the two towns to be in “states of disrepair” and “mismanaged.”

The interim order gave the municipality two weeks to put an end to sewage pollution and provide a continuous supply of clean drinking water. Failure to do so would allow the citizens to “take control” of the infrastructure, and the municipal manager would serve a minimum 90-day prison sentence.

The municipality did not meet the terms of the order and the citizens gained control.

By early January, Willie Jones, a local engineer and head of Jones Masjiene – a family business of 20 years – was at the helm of a team repairing the water treatment and sewage works. Within days, they were supplying clean water and releasing clean sewage effluent. The water was so clean that on Feb. 21, national news programme Carte Blanche posted a Twitter video of Jones drinking treated water from the Koster sewage plant after the citizens had fixed it.

Despite the municipality failing to meet the terms of the court order, the municipal manager avoided the 90-day prison sentence through a subsequent court appeal. Nonetheless, Peens explained that the citizens had not wanted to manage the plants on a permanent basis, only to intervene. An expansion of the initial interim court order on January 12 had ordered the municipality to appoint an “implementing agent” to take future control of the water and sewage infrastructure.

Magalies Water, a state-owned company – originally established in 1969 to provide water to the platinum mines in nearby Rustenberg – was appointed as the implementing agent. Once they took over on March 17, 2021, water supply problems promptly re-emerged.

A partial victory

Two weeks after Magalies Water took over, the supply of water in Koster began to fail.

“We get water for maybe an hour, hour-and-a-half in the morning,” said Kenalemang Morule, who lives in a household of four adults in Koster’s Hospital Heights, within a stone’s throw of the water purification plant.

Interviewed in October this year, Morule said water normally flows from the taps from about five until six in the morning. “We open the taps when we go to sleep, so that the [sound of running] water will wake us up,” he said, adding that occasionally the taps stayed dry for days and even weeks. “We can go for three weeks without water,” he remarked.

When that happened, people bought water from those who had boreholes, such as the Bem-Vindo lodge. The going rate was about R5 ($0.30) for 20 litres. For those without cars, wheelbarrows were used to cart the water drums and buckets.

Resident Joseph Moeti said from January to March 2021, “when Jones was in charge,” the water “was good.” Moeti said the water was clean and the supply was regular, and his team even painted the fence around the water purification plant.

“After March (when Magalies Water took over), everything went down again,” he said.

“Jones is a white guy, but he was a good guy,” Moeti added.

Pensioner Mary Montsho, who lives further down the hill in the area called Reagile, said she also only received water “for a few hours” a day, adding that “sometimes it’s dirty.”

Like her neighbours, she said she filled buckets and barrels when the water was flowing, in order to provide enough for the needs of three adults and three children in the house, the youngest just 36 months old.

While Montsho, Moeti, and Morule all said they drink the water supplied, data from the Department of Water and Sanitation site, captured on October 11, showed water quality in Kgetlengrivier municipality was “bad.” It had a microbiological compliance of 93.8 per cent, indicating the presence of faecal coliforms such as E.coli. According to the Department of Water and Sanitation regulatory dashboard, the minimum drinking water requirement in order for the water to be labelled “good” is 97 per cent.

The water was, however, achieving “excellent” status for chemical compliance. An inspection of the sewage effluent released into the Koster River revealed a clean outflow, showing that whatever sewage reached the plant, was being effectively treated. This is misleading though, as not all the towns’ sewage was reaching the sewage works. A significant leak a few hundred meters above the sewage works was evident, with raw sewage running down what appeared to be an old furrow, towards the river.

Peens is currently involved in ongoing litigation to remove the underperforming Magalies Water and have Pionier, a for-profit company started by the civil society group Afriforum, be appointed as the implementing agent.

An example for others

The initial, but significant improvement in water supply and sewage treatment in Kgetlengrivier municipality spurred residents of Mafube municipality in the Free State to take similar legal action.

In January this year, the Mafube Business Forum took the municipality to court. They obtained a judgment from the Free State High Court in April ordering the municipality, with oversight by provincial authorities, to immediately cease the pollution caused by dysfunctional sewage plant operations. As in the case with Kgetlengrivier, legal costs were ordered to be paid by the municipality and the relevant provincial authorities, who were also cited as respondents.

However, Jacques Jansen van Vuuren, who is chair of the Vaal Dam Reservoir Catchment Forum and liaison officer for the Mafube Business Forum, said despite the court’s order, no action has yet been taken by the municipality or the provincial government.

“We are going to court to see if we can get contempt of court charges against those responsible,” Jansen van Vuuren said.

He explained that untreated sewage from the towns within the municipality – being Frankfort, Tweeling, Cornelia, and Villiers – was all flowing to the Vaal Dam, which is the drinking water supply for Johannesburg. Along with other failing municipalities, this contributes to the ongoing threat to Johannesburg’s drinking water supply.

Furthermore, data shows Mafube municipality fails to report on the quality of sewage effluent, despite it being a legal requirement for operating the sewage works. With all compliance and monitoring levels at zero, it appears the municipality is also not reporting the quality of its drinking water.

Jansen van Vuuren added that there was currently no drinking water being delivered to the town of Cornelia. He said when they met with the municipal manager on Oct. 24, two days before speaking to this reporter, Cornelia had been without water for four days. He said the municipal manager did not provide an explanation.

Millions of people at risk

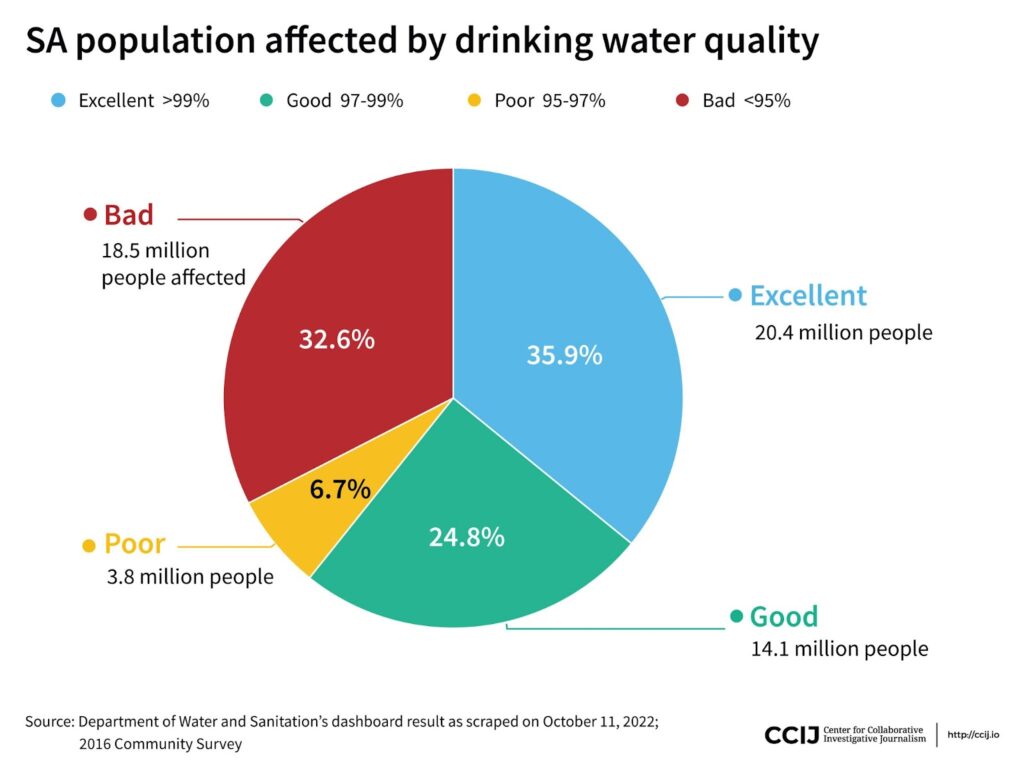

The failures are not limited to these municipalities. Data shows that almost two-thirds of South African municipalities responsible for supplying drinking water to residents, are either failing to provide water that meets the minimum drinking standards, or are simply failing to test the water they supply.

Not all of South Africa’s municipalities are responsible for treating and supplying drinking water to residents – many municipalities are supplied by water boards which are state-owned companies – but of the 144 municipalities that do, 94 of them were failing* as of Oct. 11. These municipalities are responsible for supplying drinking water to at least 22 million people, when matched against the 2016 Community Survey.

Exacerbating the situation, 112 of 144 (77 per cent) of these municipalities which supply drinking water, were polluting streams, rivers, and oceans with untreated or partially treated sewage. Overlapping drinking water and sewage treatment failures were evident in 81 municipalities.

These statistics are extracted from the Department of Water and Sanitation’s own publicly accessible water and sanitation data repository.

And geolocation and field research reveals that in many cases where sewage works are, or have been failing, such as in Winburg in the Free State, Emalahleni and Standerton in Mpumalanga, Buffalo City in the Eastern Cape, and Koster and Swartruggens in the North West, the untreated or partially treated is polluting the dams from which drinking water is extracted.

There are also communities such as Mazista and Mogogelo in the North West Province, Makhanda, Fort Beaufort and Butterworth in the Eastern Cape, Mbokoto village in Limpopo, and the entire Ugu District Municipality on the KwaZulu-Natal south coast, which do not receive water, or have suffered water outages lasting days or even weeks. These are just some examples extracted from a current news search.

South Africa’s largest city, and the country’s economic hub, Johannesburg, is not exempt. Although water to Johannesburg is supplied by Rand Water – a state-owned company – and meets quality standards, water distribution is a municipal responsibility, and this year for the first time, water distribution to large parts of the city is failing. Unlike water shortages experienced in the city of Gqeberha in the Eastern Cape, Johannesburg’s water shortages are not due to drought – the Vaal Dam from which it obtains water is about 91 per cent full – but due to infrastructure and planning failures, exacerbated by load-shedding, according to reports.

But many municipalities have been suffering from dirty water and intermittent supply for years. And in the face of inaction, or at best ineffective action, from relevant national government departments such as the Department of Water and Sanitation, citizens are increasingly taking matters into their own hands.

The official response

The Department of Water and Sanitation’s director-general Sean Phillips said it is aware of the deterioration in municipal water and sanitation services, and as a result, has developed a Water Services Improvement Programme. The programme “aims to strengthen government’s support and intervention at municipal level, more consistently and systematically,” he added.

Phillips said that, in line with this, the department “is developing rolling regional support and intervention plans,” based on the data on its repository. The support and intervention will be managed by the department’s regional offices, in consultation with provincial governments and municipalities.

However, Philliips explained that there is no provision in the Water Services Act for administrative directives for drinking water non-compliance. He said a legislative review of the Water Services Act is underway, to empower the department to enforce compliance with drinking water standards.

However, sewage pollution violates provisions of the National Water Act. Consequently, notices and directives had been served to 88 municipalities during the 2021/22 financial year, in relation to sewage pollution. These were “triggered by pollution incidents reported and proactive investigations undertaken,” Phillips explained.

“The types and nature of contraventions detected during these investigations entail a vast array of incidents ranging from manhole overflows caused by blockages, malfunctioning pump stations causing sewage overflows in water resources and discharge of substandard final effluent from wastewater treatment works into the water resources.”

Phillips said “some” of these municipalities subsequently submitted action plans to address the pollution, but there were instances where the plans were inadequate, in which case the department proceeded with “further enforcement action.”

“There are also unfortunate circumstances whereby municipalities would not respond to the administrative action issued,” he added.

He said the department has initiated civil action in cases where there has been non-compliance to notices or directives issued. Two examples are Modimolle and Lekwa local municipalities, against which the courts had ordered the municipalities to take remedial action. The Modimolle municipality complied, but the department is monitoring Lekwa municipality’s implementation of the court order. You can read more about the situation in Lekwa municipality here.

Seeking accountability

Phillips explained that there are “certain circumstances” where the department would institute criminal action. He said there are currently nine municipalities facing criminal charges for contravening provisions of the National Water Act, and some of these had been initiated by the department.

Recently, a case was opened by a member of the public against the Rand West City Local Municipality, for discharging partially treated sewage into a river. The case was heard in the Randfontein Regional Court in May. The court subsequently imposed a R10m fine ($551,536) on the municipality, R7m ($386,075) of which was suspended for five years provided the municipality met certain provisions in the plea agreements.

Earlier this year, the Thaba Chweu Local Municipality received a R10m fine ($551,536) by order of the Lydenburg Magistrate’s Court, for ignoring complaints about sewage spilling into the Dorps River, and allowing waste to pile up on the streets since 2011.

But Peens believes fines issued against municipalities are ineffective. And as Phillips said, some municipalities do not even respond. Mafube Local Municipality, which according to Jansen van Vuuren has done nothing to stop the ongoing sewage pollution – despite a court order to do so issued six months ago – is a case in point.

Peens said the municipalities pay the fines with taxpayers’ money, and often much of the payment is suspended. In his opinion, the only thing that will effectively force municipalities to clean up their act, is if the responsible officials are sentenced to prison. This is why Peens was back in the North West Province High Court on Oct. 27 to push a committal application to have the Kgetlengrivier municipal manager imprisoned, per the original court order. Even if the prison sentence were suspended, it would result in the manager having a criminal record and being fired from the municipality.

This, Peens said, would set a precedent, and shock the responsible officials across all South Africa’s failing municipalities.

“Our aim is accountability,” he said.

Municipal water and sanitation compliance details

There are four main indicators used for drinking water quality:

- Acute microbiological compliance (the number of faecal coliforms such as E.coli. Maximum is 10 coliform forming units per 100ml)

- Acute chemical compliance (chemicals that would have health implications over the short term)

- Chronic chemical compliance (chemical levels that would have a longer term, cumulative impact on health)

- Aesthetic quality (colour of the water, smell, etc.)

There are three main indicators to determine the quality of sewage effluent:

- Microbiological compliance (less than 1,000 colony forming units per 100ml)

- Chemical compliance (presence of nitrates and phosphates)

- Physical compliance (oxygen demand, electrical conductivity)

Failure, for the purpose of this analysis, is determined by microbiological compliance which, according to water quality expert and Professor at the University of Free State’s Center for Environmental Management, Anthony Turton, is the easiest factor to treat as fecal coliforms do not last long outside the gut, are killed by exposure to sunlight, and can be eradicated with chlorine.

Municipalities where microbiological compliance was labelled “bad” and “poor” by the Department of Water and Sanitation, was determined to represent failure to comply with minimum standards. Those labelled “good” and “excellent” were seen to meet minimum standards.

There are also municipalities which attain microbiological compliance, but other compliance indicators, but these were discounted in this analysis. Suffice to say, failure is more widespread than even the microbiological compliance levels indicate.

The data informing this article was scraped from the Department of Water and Sanitation’s Integrated Regulatory Information System (data repository) on October 11, 2022.

This investigation was produced in collaboration with the Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism and OpenUp, with the support of the Open Society Foundation.

A version of this article was first published by GroundUp.

Photos by Steve Kretzmann

Data visualisations by Yuxi Wang

CCIJ Editorial and Design Team

- Melissa Mahtani

- Scott Lewis

- Jillian Dudziak

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter