Surviving Hell (3): Innocent Civilians Might Still Be Finding Their Way Into Operation Safe Corridor

The admission process into the OSC programme has been criticised. For this reason, and others, the credibility and effectiveness are put under question.

She was going to wait for her husband’s return, no matter how long that was going to take. She was going to wait. But three years into her wait, someone informed her that her husband was one of the men who had drunk their own urine in the face of extreme thirst at the Borno Maximum-Security Prison where he was being held, and that he had died afterwards.

Even though they had all heard of men drinking their urine for the sake of survival in prison and knew it was true, Zarah did not believe her husband was dead. Not at first.

Then weeks later, a second person who had been to the prison also claimed they saw her husband die. And then another person.

“It was not like it was just one person, you understand. It was multiple people, telling me the same thing. And so I thought there had to be truth to it,” she tells HumAngle.

And so after the third person told her, she believed it, and in inexplicable grief, observed her Iddah period — the Islamic mourning and waiting period women observe after their husbands die. They had been married for 13 years.

“The news was all over, and his parents even performed the charity rites for him.”

Her husband, Shehu*, had been one of the victims of the mass arrests carried out by the Nigerian army in 2015 during their counterinsurgency attempts when the Boko Haram insurgency reached its peak in Borno State. Zarah tells HumAngle that she and her husband had been fleeing the insurgency themselves, and he was part of the IDPs wrongfully arrested.

“We came to the military for safety but they arrested our husbands and took them to the barracks; it’s been over six years now.”

Since his arrest in 2015, she has never seen him, nor heard directly from him. What little news she got was whatever rumour brought her way. And because she, like hundreds of women at the IDP camp whose husbands were arrested in the same manner, had no way of getting official information, she believed whatever she heard, she tells HumAngle.

Sometime after she completed mourning her husband, Zarah remarried.

“After 17 months, my parents told me to remarry because we didn’t hear anything about him at that time.”

Then, one evening, 14 months into her new marriage, at the Dalori Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camp which had been her home for the past six years, a man came with a list of men who had been transferred to the Mallam Sidi Camp in Gombe State, from the Maximum-Security Prison, as part of the Operation Safe Corridor (OSC) rehabilitation programme.

Slowly, as he made his way through the list, and as she listened uninterestedly but out of solidarity with the women whose husbands were in detention, and who did not know their fate, the man read out Shehu’s name.

“She was so shocked,” the man tells HumAngle, clasping his hands together and slapping them on his chest, to mimic what her reaction that day was. She begins to laugh.

That day, after he was done calling out the names, she went to him and asked him if he was absolutely sure that Shehu was alive. He said he was. It was an official list.

Zarah received the news with mixed emotions.

She was delighted to hear that he was alive, but remained unsure what to do with her new husband, how to break the news to him and ask for a divorce.

She was also saddened by the fact that he was going to be transferred to Gombe. His transfer meant that he was close to freedom, as the programme usually took around six months.

But it also meant that he was going to, henceforth, be regarded as a confirmed former Boko Haram terrorist.

Ostracism at the IDP camp

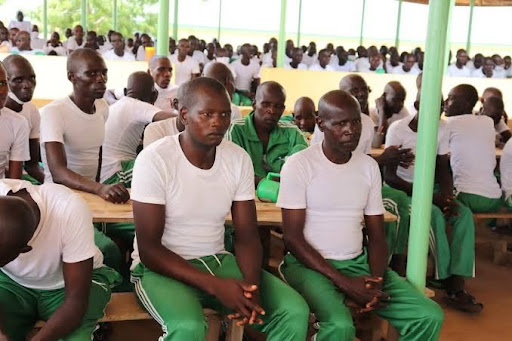

The OSC programme is run for the rehabilitation and dreadicalisation of ‘surrendered’ Boko Haram terrorists. This means that those confirmed to be terrorists from Sector 2, Giwa Barracks, and the Borno Maximum-Security Prison, all facilities where suspected terrorists are kept, are usually transferred to the camp in Gombe for ‘rehabilitation and deradicalisation’. There, they, among other things, learn a vocational skill for six months and are then released to go home.

The facility is, by all accounts, better than the prisons, as it is merely a camp and, though inmates are supervised, they are allowed to move around freely. The occupants are also referred to as ‘clients’. They get food regularly, are allowed to have their baths whenever they want, and can participate in sports.

In the other detention facilities where inmates insist on their innocence, however, there have been allegations over the years, of inhumane treatment such as congestion, and deprivation of food and water, which led to the sort of thirst that drove Zarah’s husband into drinking urine.

Therefore, according to people formerly detained at the Maximum-Security Prison whom HumAngle spoke to, there are inmates who admitted to being former Boko Haram terrorists, in the hopes that their admission would mean a transfer to the facility in Gombe, which could also mean better treatment, a chance to learn a skill, and guaranteed freedom.

However, it is not without its consequences.

“You will see children in this camp telling other children that their father is Boko Haram because they took him to Gombe. The stigma and disgust is worse for the men who are taken to Gombe,” Yakura Kumshe, one of the IDPs tells HumAngle.

But for men who admit to this, it is a game of survival, according to past inmates of the prisons. They tell HumAngle that those who insist on their innocence spend years in prison, with no prosecution nor any form of communication or idea on when they will be released. They are held in unbearable conditions. They also do not get to learn a trade or vocational skill, in most cases. When they are released without indictment, eventually, they are merely given N7,000 to N10,000 to transport themselves back home.

HumAngle has also reported the experiences of other people who were forcibly deradicalised. In an earlier report, a graduate of the programme who had first spent time in detention at Giwa barracks, told HumAngle that a confession was sometimes beaten out of inmates at the barracks.

“If you confessed, they left you alone. But if you said you were innocent, they would keep beating you. So for this reason, many people confessed they were members of Boko Haram.”

An admission seems their best shot at survival.

How effective, then, is the OSC?

The admission process into the OSC programme has been criticised, for this reason and others, and the credibility and effectiveness put under question.

For example, the International Crisis Group, which analysed the programme, reported in March this year, that “authorities should improve intake procedures to filter out civilians who do not belong in the programme.”

It also reports that “authorities channel into Safe Corridor far too many civilians fleeing Boko Haram areas, mislabeling them Jihadists, clogging the system…”

Zarah insists on her husband’s innocence, despite his being transferred to the camp in Gombe State, which seems to strengthen the International Crisis Group’s submission.

HumAngle has also done a series of reports on people who, despite insisting on their innocence and having no evidence to prove otherwise, were transferred to the Mallam Sidi camp. The clients confirmed to HumAngle that far too many of them who underwent the programme were innocent.

What will Zarah do?

The day Zarah received news of Shehu being alive, she says, she was confused and sad.

Eventually, at night, she summoned courage to tell her current husband of the happenings of the day, pleading with him to let her go, so that she could continue to wait for his return.

“I asked my new husband to divorce me since my former husband is alive. I told him that if my former husband rejects me, we can remarry again,” she says.

For a very long time, he remained silent. Later, he asked for time to be able to process the news, she tells HumAngle.

The following morning, he gave her the divorce letter she asked for.

“He released me saying he wouldn’t have married me if he knew my husband was alive.”

Now, she waits for Shehu’s return.

This report is produced in partnership with the Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD)

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter