Resettled IDPs In Borno Community Are Crossing To Cameroon For Potable Water

“When you return poor people to their community without water to drink, it makes them think about going back to where they came from.”

One of the consequences of the Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria is that families get separated across states ‒ and sometimes across countries. While Abba Gole camped at a displacement camp in Maiduguri, Northeast Nigeria, his daughter was flung as far away as Cameroon. But earlier this year, she learned that her father and other community members were resettled back in Kirawa, so she came home.

A few days after her return, Gole woke up very thirsty. There was no water in the house, as was so often the case because of a general scarcity in Kirawa. So she had to go to the neighbour’s house to fetch some for him to drink. The water was unclean and contaminated, but she did not know this.

“The following morning, my stomach started to hurt, and I began visiting the toilet uncontrollably. My friend told me I needed medicine because it was diarrhoea,” Gole recalled.

While this reporter was interviewing Gole, he had to excuse him to rush to the toilet. He looked sick and worried.

“The community is suffering from water scarcity,” he said after he returned.

“Three borehole points were constructed, but only one point is working. The one that is working doesn’t provide us with enough water and it’s very far from our houses. When you visit the water point, the queue will take from morning to evening before it reaches your turn.”

Gole taught at Kirawa Primary School for over thirty years before retiring. He is part of the 2,500 persons who got resettled in Kirawa earlier this year.

The recent relocation of internally displaced persons by the Borno State Government has exposed a new dimension of humanitarian gaps in resettled communities.

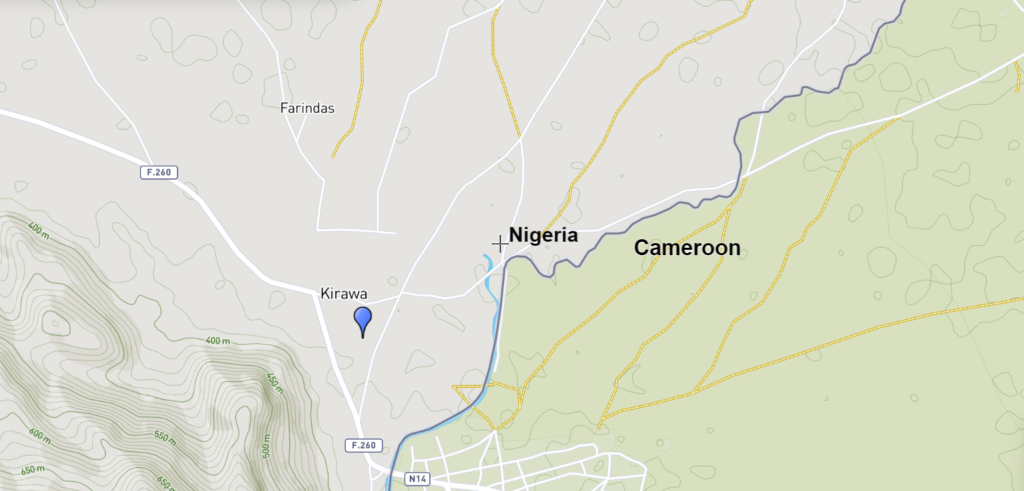

For Kirawa, a town sharing borders with Cameroon, asides other pressing humanitarian needs, residents identified water scarcity as their number one challenge. The lack of adequate water has exposed them to health risks.

Locals cross the border into Cameroon to get water despite the challenges they face in the process, such as the water being sold at an exorbitant price and the early closure of the borders.

“After eight years, we have returned, but water scarcity is the biggest challenge despite the construction of three water facilities around the community by the Borno state government,” said the District Head of Kirawa, Abdulrahman Abubakar.

Umaru Alhaji Hamidu, a wheelchair user who resides in the community, has just returned after spending seven years at an IDP camp in Pulka, Gwoza Local Government Area.

“The only borehole that is working is too far from my house and there are no children to fetch for me. If I need urgent water, I enter Cameroon to buy water to drink and for domestic use,” he said.

“We buy the water very expensive in Cameroon despite the long distance.”

Another resident alleged that they even get harassed by security personnel at the functional water point in Kirawa. He also complained that they sometimes lock the water pump and give “silly excuses.”

“Sometimes, when you visit the only functional water point located at the Primary School Area, you face harassment by security personnel. This is very bad. When you return poor people to their community without water to drink, it makes them think about going back to where they came from.”

Bathing and laundry, for many, is not something they do regularly due to the difficulty of accessing water.

“Is it not when the water is enough before you use it to wash either your body or clothes?” Ali Mamman, 24, asked.

Similarly, the returnees who take part in rebuilding their destroyed houses also have difficulty because of the same challenge.

Houses in Kirawa are either made with mud or bricks made from cement and sand. Both methods need water for construction.

Returnee Abdullahi Dahiru’s house used to be made of cement blocks until it faced the wrath of destruction by the armed conflict by insurgents in 2014.

“I am excited to return home despite my house being destroyed. It took me many days to gather the water to mix the mud for the reconstruction,” he said.

“Even if I have the money to build a house with cement brick, where will I get enough water in this situation when the water is scarce?”

According to the community members interviewed by this reporter, when the governor visited, he ordered the construction of water facilities in the community to ameliorate the urgent water need.

“The government constructed three solar-powered borehole water facilities earlier this year when Kirawa was resettled. But amongst the three, only one is functioning within just a few months of construction,” the district head, Abubakar, said, a fact that was later confirmed by HumAngle.

The three constructed solar-powered water points are located at Kirawa Primary School Area, Tashan Kada Area, and Drumyadi Area in Kirawa.

The functional water point is sited in the Kirawa Primary School area. But because it is far from the heart of the community, people travel long distances to get the water.

The borehole at this point has a peculiar problem too: it only runs when the sun is out during the day. When clouds form, the water stops running.

Hydrogeologist and consultant on water projects, Dr Musa Aji, suggested the borehole constructions may have been done without a professional geophysical survey, good engineering equipment, or adequate electricity to power the pumps.

“Geologically, Kirawa falls under the basement areas. Basement areas are locations where underground water occurs in pockets and fractures. This implies that without detailed geographical surveys by experts and proper application of professionalism, you end up drilling a borehole in the wrong place and water seizes eventually,” Aji said.

“You said the water points in Kirawa are solar-powered boreholes? This may be attributed to so many things.”

He also identified other possible problems as the low hill nature of the area, the selection of the borehole pump, and the installation of solar power.

“The selection of compatible pumping machines is crucial in areas like Kirawa. For example, if you want to install a pump in a borehole, you need to carry out a proper pumping test to determine the maximum yield of that particular borehole. Otherwise, the borehole will eventually stop functioning in a short time,” he explained.

“The installation of solar power itself nowadays is really something to be concerned about. We received several community-based complaints against solar energy on boreholes; they complained the solar equipment is not functioning optimally. Most of the time, we discovered most of the solar designs for public consumption are not compatible with the borehole pump machine installed. Or it is installed unprofessionally without effective supervision.”

Aji noted that the government alone cannot provide everything and urged humanitarian actors to support the community.

However, the state government’s decision that banned humanitarian actors from providing assistance to newly resettled communities could exacerbate the suffering of the returnees IDPs.

It has been argued that some of the communities being prepared for resettlement are not ripe for such exercises and the IDPs returning there are at risk of facing even harsher humanitarian challenges.

This report was produced under the HumAngle Accountability Fellowship, with the support of the MacArthur Foundation.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter