REPORT CARD: Under Buhari’s Administration Nigeria’s Humanitarian Crisis Deepened

The Muhammadu Buhari administration’s response to humanitarian crises resulting from conflict and environmental disasters was inadequate. Its efforts were beset by corruption, mismanagement and lack of political will.

Solomon Dalyop, a community leader in Plateau state, north-central Nigeria has been hoping for years that a day may come that the government will come to the aid of his people.

But even though it was promised, the aid never came.

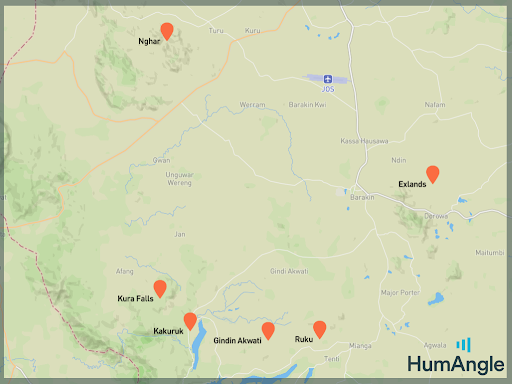

In June 2018 assailants killed at least 86 people across 43 villages in Barikin Ladi and Riyom local government areas of Plateau state.

Residents were forced from their houses, dislocated from their communities, and many are still living in places far away from where they lived.

In the aftermath of the attack, Vice President Yemi Osinbajo paid a condolence visit to the state and met with stakeholders.

The Vice President pledged to support the Internally Displaced People with ₦10 billion to help the victims of the terror attacks resettle and rebuild their homes.

It is now five years later, the people said the government is yet to redeem the pledge it made to support them. Some have found their own means to rebuild their homes, while others are still taking refuge in other communities.

Their farmlands have been deserted, devastating to communities that are largely agrarian.

The incessant attacks and reprisal attacks in Plateau that has put many families in despondency, are the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the humanitarian crises in the country.

It is fair to say that next to the crisis in the North East, this particular humanitarian crisis appears forgotten. That, in itself, says something about the last government’s response.

Shut off

In the eight years of Buhari’s tenure, there have been several situations that have grown into humanitarian crises.

Some have come as a result of the Boko Haram insurgency, others as a result of communal clashes, farmers and herders conflict, so-called banditry and increased flooding due to climate change.

Since the beginning of the crisis triggered by the war on Boko Haram, access to humanitarian aid has been severely restricted in northeast Nigeria’s conflict-affected regions.

Outside of the government-controlled areas, an estimated 1.24 million Nigerians are totally shut off from humanitarian relief, and many more millions face varied degrees of barriers to receiving life-saving aid.

For example Rann, a distant town in Borno, is particularly challenging for humanitarian supplies to reach. Roads to Rann have been severely harmed by flooding, making it impossible for food and other supplies to reach the region. Over 40,000 individuals, the majority of whom are internally displaced, lack access to food and other necessities.

Northeast Nigeria has become one of the most difficult working settings for assistance organisations due to a combination of general instability, the unpredictable and ruthless actions of the insurgents, and the complex nature of relationships on the ground. One of the most influential factors is the effect of corruption on the ability to translate humanitarian intention into demonstrable positive effect.

As of 2019, it was estimated that 7.1 million people in the region needed aid, including 2 million people who had been displaced by the violence and were now mostly residing in IDP camps inside of garrison towns built by the Nigerian military. International relief organisations have primarily restricted their humanitarian assistance to these military towns.

A further 1.24 million people are reportedly in need of relief outside of Nigeria’s military zones as of late 2019, yet they are reportedly both unreachable and unable to get humanitarian aid. Many of those who have managed to leave the insurgent-controlled areas, according to the UN, are emaciated and report being held for years in hostage-like situations by non-state armed groups with no access to basic services and suffering abuse.

After more than a decade of violent conflict, the humanitarian disaster in northeastern Nigeria has gotten worse. Over the years, the situation has intensified, causing massive displacement and destruction in addition to severe food and nutrition insecurity and a critical lack of vital medical treatment.

A recent estimate by the United Nations put the figures of those in urgent need of humanitarian assistance at 8.3 million, which it said over 80 per cent of them are women and children.

Women and children are the most vulnerable in any crisis. As a result of the desperation, reports have emerged about the forced sale of family assets, child labour, child marriage, and instances of victims being forced to “sell” sex to aid workers in return for the aid they are entitled to.

In Borno, there have been many reports of IDPs who died of hunger-related ailments. Relatives of IDPs who died in displacement camps said living has become unbearable as they stopped receiving aid.

Stakeholders have said Nigerian authorities’ performance overall is below expectations and often complicates adherence to humanitarian principles.

Last year, the United Nations in its Global Humanitarian Overview (GHO) described Nigeria’s North East as one of the world’s largest humanitarian crisis zones, with at least 8.3million people in need of assistance in 2023, saying violent conflict, climate crisis, diseases and other risks are putting their lives at risk.

Crisis spread

Other areas of the country are also in crisis. In Benue State, North Central Nigeria, From 2011 to the end of 2021, 21 out of the 23 local government areas in the state have come under attack by herdsmen, leading to the displacement of over 1.5 million people.

“The dire humanitarian situation in the state is further compounded by the influx of Cameroonian refugees into Kwande Local Government escaping the conflict in their country. The IDPs have had their livelihoods destroyed and are in need of protection, food, shelter and medical assistance,” according to the state governor Samuel Ortom.

The state and federal government, NGOs and other benevolent individuals have been coming to the aid of the displaced people, but more needs to be done. As findings have shown, the State Government could only provide shelter and other support for 15 per cent of the IDPs, leaving the 85 per cent to fend for themselves.

The ongoing terrorism of bandit attacks on farming communities in Niger State, North Central Nigeria, have driven thousands of people from their homes. Many of them have relocated to other parts of the state, mainly Minna, where they resort to begging near gold mine sites to collect money for food.

In Katsina, Zamfara and Kaduna states Northwest Nigeria, thousands of people have been displaced from their homes as a result of armed violence.

A military operation against the scores of criminal groups who roam the countryside of the North West, extorting money from communities for “protection”, or kidnapping women and stealing property, has not stopped people having to flee their homes.

Residents are compelled to welcome the displaced persons swarming into the city from every corner of the state due to the escalating banditry in the region.

With more than 50,000 individuals residing in official IDP camps or with relatives, around 30 communities in Zangon Kataf, Kauru, Kajuru, Chikun, and Kaura have been displaced, some even permanently across Kaduna.

Flood

In 2022, a flood swept many parts of the country, which led to the death of at least 600 people and the displacement of more than 2 million from their homes. Over 110,000 hectares (272,000 acres) of farmland were affected.

The floods have worsened the food crisis in the northern regions, one ruined growing season for many farming on the floodplains could lengthen the “hungry season”, the period between the end of the year’s stores and the next harvest, tipping millions into starvation.

More people have been forced into fleeing their homes, or they are in need of help to rebuild them.

The government was slow to respond, Buhari only made a comment about the situation weeks after the seriousness of the floods were revealed.

Foreign crises

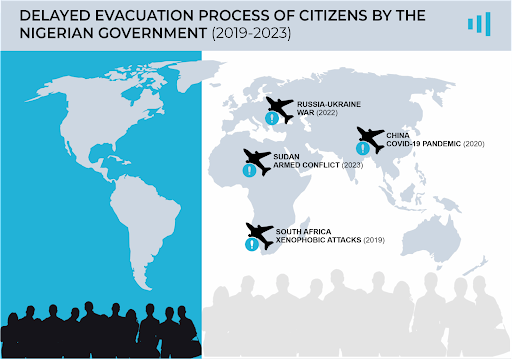

When crises hit Nigerians in foreign countries too, the government has been found wanting.

The ongoing crisis between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces has further exposed the Nigerian government’s lack of preparedness for such issues. Even with the private sector’s support, many Nigerians were stranded in Port Sudan and Halfa for weeks.

It wasn’t the only time in the past eight years that Nigerians have been stuck abroad. Whenever this has happened, the country has been slow in assisting its citizens.

The government had trouble extracting Nigerians from South Africa after there were xenophobic attacks on them. Retrieving citizens who wanted to leave China at the start of the Covid 19 Pandemic was a trial, and getting Nigerians out of Ukraine in February 2022 when Russia launched an attack against the country proved a test of the government’s ability.

This is even with the establishment of the Nigerians In Diaspora Commission (NIDCOM), a government agency created in 2019, with the aim of reaching out to Nigerian communities abroad through their various groups, organisations and professional bodies, among others.

Defeated dispersed defenceless

In all the states, thousands of displaced individuals share three characteristics: they are defeated, dispersed, and defenceless. Some of them became beggars, while some who vowed never to beg are now gradually starving to death.

In the last eight years of Buhari’s presidency, the administration established institutions that were supposed to alleviate the suffering of people displaced from their communities.

In addition to the National Emergency Management Agency, since 1999 the country’s disaster management arm, the Buhari administration created the North East Development Commission. It is responsible for receiving and managing funds allocated by the FG and international donors for the resettlement, rehabilitation, integration and reconstruction of roads, houses business premises of victims of insurgency and terrorism as well as tackling the menace of poverty, illiteracy, ecological problems, and any other environmental and development challenges in the North East.

For the first time in the country, a ministry was established for humanitarian affairs. The Federal Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs, Disaster Management and Social Development was launched on August 21, 2019.

Graft

But these institutions have been hampered by poor performance and graft.

The Federal Government launched poverty alleviation programmes, but they have been beset by corruption allegations, such as the N-Power scandal, Conditional Cash Transfer, Government Enterprise and Empowerment Programme and National Home Grown School Feeding Programme.

In September 2020, during the Coronavirus pandemic Nigeria’s anti graft agency ICPC said 2.67 billion naira that was meant for feeding school children during the lockdown ended up in personal accounts. The minister denied the allegations but despite the denial, many Nigerians have described the entire school feeding programme as a sham.

The programme did not get the attention it deserves because of lack of credibility, inconsistency, politicisation as well as absence of proper monitoring and evaluation.

In 2017, the former president set up the Presidential Initiative on the North East, (PINE), as the area that the Boko Haram insurgency has ravaged. The intervention was also flawed by corruption and mismanagement.

A report by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the National Human Rights Commission between 2015 to 2017 documented how funds that are meant for victims of the insurgency were diverted by government officials of the PINE. According to the report, the amounts budgeted were inadequate, billions of naira were not spent as they should have been, and “out of 249 trucks carrying 10,000 metric tonnes of maize released by the Federal Government for the benefit of the IDPs in the six states of the North East, 65 trucks were diverted and did not reach their intended destinations”.

Where Buhari’s government intervened in humanitarian crises, the process has been marred by corruption. That led Nigerians to lose hope in the entire administration’s handling of the sector. The disappointment has been all the more galling as the administration came to power on an anti-corruption slogan.

Insensitivity

The Buhari administration has publicly accepted that the situation in the country is severe, but there is a question over whether the response has been serious enough.

“We cannot deny the fact that we have a very dangerous humanitarian crisis in our hands,” he told the African Union in Malabo, Equatorial Guinea at a 2022 summit.

At the event, the AU was launching the African Humanitarian Agency, aiming to arrest the issues affecting the continent and also to prevent adverse effects of humanitarian crises through “addressing root causes”.

But the Nigerian president supported it with an initial pledge of only $3 million, just a third of one per cent of the cost of averting humanitarian disaster for one year in Nigeria’s North East according to the UN.

The ex-president also previously made statements that showed an insensitivity to the plight of the displaced people. This might be the reason he has performed poorly when it comes to the humanitarian crisis in different parts of the country.

He once accused the UN of exaggerating the gravity of Nigeria’s crisis. He said, “blatant attempts to whip up a non-existent fear of mass starvation by some aid agencies, a type of hype that does not provide a solution to the situation on the ground.”

Looking at these events, it could be said that the previous administration under former President Muhammadu Buhari has performed poorly in its handling of the humanitarian crises around the country.

When he took over on May 29, 2015, the humanitarian crisis in regions outside the North East was minimal. Now, eight years later, in the North East, North West and North-Central millions more people have been forced into desperate situations.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter