Relatively Few Women Have Been Detained At Giwa Barracks. Ya’ana Was There Twice.

The first time she was released from the detention centre, Ya’ana was told she would be locked up again if she ever narrated her ugly experience to anyone. But then, that is exactly what she does.

“Hajja Ya’ana has come!”

Unlike the other people she entered with, Ya’ana Kaumi*, 42, was not a strange face to the people at Giwa Barracks. As soon as she stepped within the barbed, over 10-foot-tall walls of the facility, many of the detainees and officials recognised her chunky frame though it was about an hour past midnight.

Cries of “Hajja Ya’ana has come!” rent the air. She had been here before, this detention centre where anyone suspected of having ties with Boko Haram is kept arbitrarily and often without trial. This place where inmates died in droves due to notoriously cruel conditions. She was lucky to have made it out the first time. But she wondered if her lightning of good luck could strike the same spot twice.

Now, sitting on the thickly carpeted floor of her chamber in Bulabulin Ngarannam as she eagerly tells her story, it is obvious that it did.

…

Bulabulin Ngarannam is a rural community about an hour’s drive south of the heart of Maiduguri. The roads are parched and untarred. The residences, mostly made with cement blocks, are tall and unpainted. Locals say the unusual height of the buildings and the absence of ceilings are deliberate to make the desert climate bearable. Notably, the ghostly brown of the road and colourless structures erected on them contrast sharply against the forest green of the Neem trees scattered across the landscape.

The town has not always been this tranquil. About a decade ago, it buzzed with terrorist activity and hosted many of Boko Haram’s fighters. It was considered the terror group’s headquarters. There, its members abducted women and killed several residents, including one cleric who ratted them out to the military, Sheikh Ali Jana’a. They also dug a vast network of underground tunnels under the stronghold through which they smuggled in small arms and light weapons.

In late 2012, soldiers had to seize control of the place, forcing out Internally Displaced People, expelling residents from their homes, and making both entry and exit difficult as helicopters patrolled from the skies. But it was not until the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF), a paramilitary vigilante group, joined the armed forces in hitting the streets of Maiduguri the following year that the insurgents were dislodged.

Ya’ana has lived in this town for a total of 17 years, so she was there when it all started.

“They used to preach in the centre at the railway terminus. They also went to Millionaires’ Quarters and some other places to preach. When they started the jihad [war] in 2009, they were selling their assets and those of their wives,” she recalls, gesticulating with her right hand as she reclines on a hefty mattress.

“In 2011, some came back and settled in areas like Abba Ganaram, Kawar Amila, Shehuri North, and Kaliari. There were new faces that come and go. They became part of the community and settled. They were reading their books and later they started killing people that condemned them.”

One day, in 2013, there was a gun battle between the Nigerian military and Boko Haram in the area, which led to the death of at least one soldier and one terrorist commander. The troops then returned in many vehicles and engaged the insurgents for long hours. The following day, the group’s members went from house to house to retrieve the dead bodies of their associates for burial. Ngarannam subsequently became extremely dangerous as terrorists swarmed the community.

Life with the insurgents was “very hard”. Visitors and vendors, including water-cart pushers known locally as mai ruwa, were not allowed in. If Boko Haram members saw strangers, they would capture and slaughter them, suspecting them to be spies.

At first, only three buses shuttled between downtown Maiduguri and Ngarannam. But then, one of the drivers was arrested by the military and detained at Giwa barracks. Another one, Ya’ana’s in-law, was also arrested. The third driver left for Kano, leaving locals who needed to go to town with no choice but to trek.

Ya’ana herself could not bear the hardship and eventually travelled south to neighbouring Adamawa State, where her husband lived.

When she returned to Maiduguri about 18 months after her trip to Adamawa, Ya’ana did not go to Bulabulin Ngarannam. Instead, she moved to Umarari, a small community about three kilometres to the south, where she resumed her food-selling business.

It was as a result of this business she got into trouble with the military – twice.

The first time was through one of her attendants named Ya Kaka, a former Giwa barracks detainee who was broken out alongside hundreds of others during the infamous Boko Haram attack of March 2014.

She had been working with Ya’ana for years and lived in her house back in Ngarannam with 12 other young girls. The insurgents forcefully married all of them. They would visit during the day and leave at night. When civilian vigilantes prowled in the area for terrorists and could not find any, they instead arrested the girls and women, about 47 in total, and drove them to the Giwa military detention facility. When the jailbreak took place, only seven of the girls, including Ya Kaka, returned. Others went with the invaders to their camps.

Back in Umarari, months later, a fight erupted between Ya Kaka and the landlord’s wife who accused her of ogling her husband. Out of spite, the lady then reported her to nearby officers of the CJTF, telling them she was a Boko Haram member.

“I was not around by then and when I came back they called me. They accused me of hiding a member of Boko Haram in my house,” Ya’ana says, as she keeps herself cool with the aid of a woven straw hand fan. “They first took us to a military checkpoint in Ngarannam where we spent one night and later they took us to Giwa.”

Newcomer

While it was Ya’ana’s first time in the detention facility, Ya Kaka was no stranger, and as soon as she was sighted, the officers started celebrating her return. They gave them a mat, blanket, and praying mat. At the time, there were only seven cells, six for men and one reserved for women. In that one cell, which Ya’ana describes as tiny, there were 57 girls and women and three infants. Sometimes, people give birth while in detention.

The only death recorded in Ya’ana’s cell during her stay was of a woman in labour who had earlier been “severely punished by the military”. There were other cases of torture too, including the waterboarding of a girl accused of having explosives.

“The room was very small,” Ya’ana emphasises, visibly agitated by the memories flooding her mind. “We slept like how you pack razor blades. We urinated and passed stool in plastic buckets placed in the cell, so there was smell all over. We defecated in nylon bags and threw them in one bucket and urinated directly into a second one. The entire place smelled. There were lice, mosquitoes, and the rest.”

The bucketfuls of stool and urine were emptied every morning and, at least once a week, they were permitted to have their baths.

Despite the overcrowding and poor state of the cell, the male detainees had it much worse. They had bigger cells but also an enormous population, which meant they could not even turn on their sides while resting. They also had smaller food portions. The women used to send their leftovers to them, especially in the early days when the “food was good” and they were served thrice daily. And while the women were allowed to occasionally step out of the cell to bathe and pray, male detainees did not enjoy the same prerogative.

Perhaps as a way to decongest the male cells, tens of gun-toting military officers, including many from other posts, now and again visited at night, called out names of men-detainees, and disappeared with them into the hazy night sky. Such extractions took place about 13 times while Ya’ana was there and each one could involve between 25 and 80 men. It was the last they saw the detainees whose names were on the roll. She would later learn that the men were getting transferred to the Borno Maximum-Security Prison.

Because the female cell was next to them, the soldiers would cover their windows so they could not see what was going on. But, driven by sympathy and curiosity, the women would secretly watch with the aid of their waste disposal buckets.

“When they do this kind of thing, they wouldn’t come near us for three days or so. They would allow us to go out and even take bath.”

Ya’ana was 35 in 2014 and so was one of the oldest female detainees instinctively tasked with settling disputes. But about nine others were more advanced in age, one woman as old as 75, others between 60 and 65 years. While some of the younger girls were arrested because they had spent time with Boko Haram fighters in the bush, the elders’ crime usually was that they had sons, in-laws, or siblings who were suspected insurgents. The CJTF conducted most of the arrests, “took them to sector [a military base] for interrogation, wrote what they want, and took them to the barracks.”

Among the young female detainees, Ya’ana recalls that at least seven hung around closely with the military personnel who were considered their “boyfriends.” The officers regularly called them out of the cell and bought them extra food. Unlike their counterparts, they were also free to step outside.

There were always new arrivals at Giwa barracks. Fresh detainees were brought in daily, sometimes as few as two, other times as many as 20.

“When they bring the men, they would tear their clothes and leave them with underwear and handcuff them,” says Ya’ana, leaning forward and folding her arms behind her back. “They would then ask them to lie down on gravel in the sun and would not put them in a cell until night time. They also poured water on them and beat them with canes.”

The global research and advocacy group, Amnesty International, has reported extensively about the conditions of inmates at Giwa barracks, confirming Ya’ana’s experience.

In a 2016 report, it noted that as of May 2015, women’s cells had about 25 people each and men’s cells had 160 inmates each. It further stated that just between January and April 2016, 149 people died as a result of starvation, overcrowding, and torture.

“According to witness testimony, the majority of detainees were men and conditions were worse in their cells,” Amnesty International wrote.

A second report released in 2018 revealed that women detained at Giwa barracks typically included victims of abduction or forced marriage by Boko Haram members, those who arrived in recaptured towns without their husbands, and women who had family members suspected of being Boko Haram members.

“None of the women released from detention that Amnesty International interviewed had ever been charged with a crime, or given any opportunity to challenge the lawfulness of their detention in front of a judge, or knew of any other women detained with them who had been. The vast majority had spent between six months and two years in detention,” the advocacy group said.

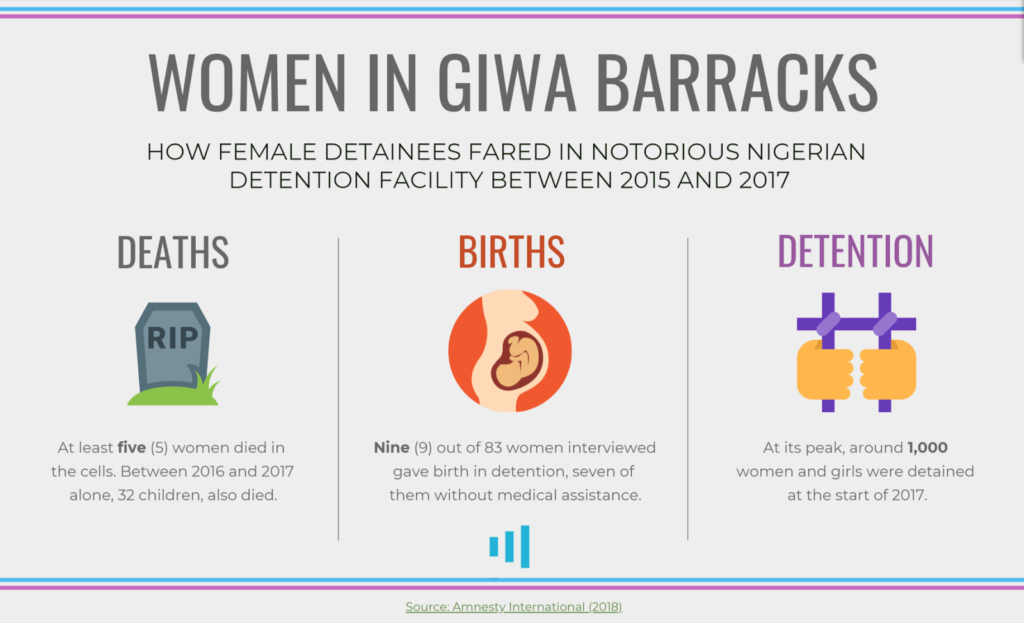

It added that between 2015 and 2017, at least five women died in the cells and nine gave birth while in detention, seven of whom received no official assistance.

Freedom

A year and a month into her time in Giwa barracks, in mid-2015, the military officers announced the names of over 20 women and about 40 men who were selected for release. She was lucky to be among. Their pictures were taken and they were transferred to a different cell. Others, whose names were not called, had to be patient, they said.

“After 10 days, they came and said if we disclosed what we saw there, we would be brought back,” Ya’ana says.

Shortly afterwards, they took them to Mai Malari barracks where a ceremony was conducted for their release. It was during the Muslim fasting month of Ramadan, two-thirds of which they had spent in detention. Ya’ana remembers they were likely over 200, but a local press report published in the period placed the figure as 182, including 100 men, 24 women, 40 boys, and 18 children. Then army spokesperson S.K. Usman explained that the release was part of the National Army Day commemorated every 6th of July.

At the ceremony, the Borno state governor at the time, Kashim Shettima, addressed the former detainees and, according to Ya’ana, gave them two wrappers and N10,000 each. A large school bus then arrived to transport them to the government house before they embarked on the journey home towards renewed freedom.

Home, for Ya’ana, was no longer Umarari where she was picked over a year earlier. She returned instead to Bulabulin Ngarannam, which had been restored to its old sleepy self.

“People felt happy and were coming to see me. My husband also came from Yola and joined me,” she says, before drinking from a sachet of cold water. She was particularly glad to reunite with her young daughter, Fanna*. Her son, Muktar*, had been missing for some time.

A second journey to hell

Ya’ana’s second arrest was foreshadowed by a bang on her gate at half-past midnight. It was raining outside. When Fanna, her daughter, opened to see who was knocking so loudly at such an odd hour, three soldiers and a fourth man stormed in. “Are you Ya’ana the food seller?” one had asked her, to which she had replied no. Ya’ana, who was previously seated and applying henna to her feet, got up to pick her hijab and saw one of the uniformed men go through her drawers, wardrobe, and three-seater sofa. She recognised some of them because they had regularly patronised her restaurant.

“We went outside and entered a vehicle where I met two other people I know,” she says, describing the scene vigorously with both hands. “The vehicle went with us to the front of another house where they picked another man. They took us to 7 Up where we found three others. And then they moved us to garrison command [7th Division, Maiduguri] where we met two others; and the next morning another man brought himself, making us 11, two women and nine men.”

Fanna remembers it was Aug. 2017. Her mother had thought the soldiers came to buy food as usual. The fourth man, she says, had a head covering that only revealed his eyes. She also remembers she had asked her mother what she did wrong, but the latter was just as clueless.

The arrested men and women were transferred to Giwa barracks after some days, at about 1 a.m. Ya’ana says they took their names and started beating the men before locking everyone in their respective cells about an hour and a half later. The following day, the officers allowed them to take their bath, gave the women wrappers and the men shorts, and returned them to their cells.

The detainees were not informed of their offences until about a week later when they were taken for questioning. On Ya’ana and the second woman, they pinned the crime of selling food to Boko Haram members.

“Ya Mairu sold water and rented house to Boko Haram. Kyari Goni hired a motorcycle to Boko Haram which they used to kill people. Mai Ati was a member who used to go [Boko Haram founder] late Mohammed Yusuf’s place. Modu Bulin is a friend of Boko Haram. Yaa Tuja was a village head who left for Damboa and refused to come back when the area was recaptured. Bakura was a CJTF member who aided Boko Haram to get mattresses. And Abatcha, also a CJTF member, was accused of cattle rustling.”

Ya Mairu, the water vendor, would later die about four months into detention. He was said to be living with HIV but, depressed, he refused to take his antiretroviral drugs.

The conditions had grown worse since Ya’ana’s first time. She estimates there would have been over 7,000 inmates, including several hundreds of children, when she was eventually released. But four new cells had been built to accommodate more people, including one they called the luxurious cell which had over 500 inmates. CCTV cameras had been installed too and some cells, especially one for underage detainees, had plasma televisions.

But then, the “torture was worse than before”. The food was not enough for both male and female detainees. Tens of people died on some days due to hunger. She says, during the 18 months she spent there, about 500 people must have starved to death. Piles of corpses were a common sight. At some point, officials of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) visited with foodstuff, blankets, soaps, and disinfectants. Fanna would later confirm that her mother looked emaciated after her second detention compared to the first time when “we were even surprised she was looking good”.

The sexual exploitation of female detainees continued, but many did not mind because of the advantages that came with it: more food, drinks, clothes, and whatever donations they got from humanitarian organisations such as the Red Cross.

“They would come in the night and pick the ones they want. Sometimes if there was a sick person, they would call some of the girls to help. No one would know what happened. There was one girl whom we suspected gave birth to a child for the military; she is now in the Bakassi IDP camp,” Ya’ana narrates.

Giving special treatment to certain female detainees was not the only shape corruption took at Giwa barracks. Relief materials from the ICRC were often not distributed fairly. The aid workers would give to a few women to flag off the humanitarian effort and then the military officers would take charge of the rest. Ya’ana alleges, for example, that while Red Cross would give four wrappers per person, the soldiers would ask three detainees to share two wrappers. And whatever remained? “They would go and sell them.”

“There were wives of the military who sell things there; they gave them to go and sell for them. And if detainees had valuable jewellery, they seized them and gave them to those women to sell for them,” Ya’ana states.

The road to her second release was filled with a chain of strange events. About 14 months into her detention, the authorities called her out to show her a photo of her house and asked why it was always locked, to which she replied she did not know if her daughter was still residing there. They also asked about the people she was arrested with. Then they took her to see her village head (Bulama), ward head (Lawan), and others from her community in Maiduguri, who confirmed they knew her as a long-time food seller. Then they collected Fanna’s phone number. Then she was screened among other detainees for HIV infection. They had to open new files, she says, because the old ones had been lost. Afterwards, they brought greetings from Fanna. Then came visits from the Presidential Committee on Special Detainees in Prisons and Other Detention Facilities, which was set up in Dec. 2016, as well as the Legal Aid Council. Then, they took her with others to the Bulumkutu Rehabilitation Centre in Maiduguri.

“After one month, they discharged us, brought us in a convoy of vehicles and handed us over to our Lawan.”

The Nigerian Army has seldom reacted to allegations about arbitrary arrests, wrongful detention, and inhumane conditions at detention centres such as Giwa barracks. Former army spokesperson Sagir Musa, however, described the claims as “malicious” while speaking to The Guardian last year.

Brig. Gen. Mohammed Yerima, Musa’s successor, tells HumAngle in a phone interview that he does not “know anything about detainees” at the barracks, possible improvements in their conditions, or observations about soldiers having sexual relations with female inmates.

He also denies allegations that relief materials from the ICRC were intercepted and sold by soldiers at the detention facility.

“What have soldiers got to do with Red Cross? How will Red Cross material even reach soldiers?” he asked. “Any of the humanitarian agencies, if they want to go into the interior, we give them protection. That’s all. We don’t have business with their materials. How will the materials come to us?”

Awaiting mother

As soon as she watched her mother being led away in the military van like a criminal, a tearful Fanna scampered to her former husband’s house. She needed someone to break the news to and comforting words.

“I was crying and he was cooling me when we heard people crying at Ya Mairu’s house; we didn’t know whether they arrested him too or he had died,” she recollects.

“Then I told one army RSM [Regimental Sergeant Major] in the area that they had arrested my mother, and asked what she did. He said he didn’t know. We went around the area and couldn’t see her; they had gone with her.”

Rumour started spreading among the residents that Ya’ana had become a Boko Haram sympathiser since she was selling food to the members. When the talks became unbearable, Fanna sent her children to their father, her ex-husband. She avoided staying in the house frequently because of the stigma that came with her mother’s arrest, which was also affecting food sales.

It got worse.

“There was one soldier who was looking after our house and in the night he would still send two of his boys to guard the house. Then people started saying that I was inviting men to our house because my mother was not around. The soldier prevented me from moving around. He was giving me N20,000 in a month and bought foodstuff for me.”

Other residents were uncomfortable and reported Fanna to the community leader. The soldier, in turn, told them Fanna was his wife, asking rhetorically what assistance they had ever rendered to her. When the Nigerian Army transferred the officer to Abuja, she followed him but returned to Maiduguri after some time. Meanwhile, the talks still simmered.

Fanna was only 15 when her mother was first arrested in Umarari. Armed with Ya’ana’s picture, her husband had gone to the Borno Maximum-Security Prison to enquire about her status. The prison authorities, Fanna says, asked him to give up on the case and threatened to lock him up if he persisted.

“Then I started crying, saying to myself, ‘I have no mother and my father lives far away. I don’t know what I to do with my life.’”

After about a year, Bulabulin Ngarannam, which had been sealed off by the military, was reopened so people could return to their houses. Fanna had no mother to run to for help during her first pregnancy and after she gave birth. And when her husband became fatally abusive, one-time kicking her tummy during a second pregnancy, she could only seek backing from soldiers and CJTF members in the community who threatened to have them divorced if he assaulted her again. He did, only after two days, and the couple went their separate ways.

“We were divorced but he kept bringing food to me. But anytime he came and found me with people, he complained that people were coming to see his wife. So I told the CJTF chairman that I didn’t want him to come to my house again and I didn’t want his food. He was an Indian hemp dealer,” she says.

She sold two kufi caps and used the proceeds to kickstart the food-selling business. Then, she rented out rooms in her mother’s house to tenants and invested more money in the restaurant.

Around that period, she got another rude shock. Her brother Muktar, who is five years older and was living with their uncle, had been missing for two weeks.

She gave birth to her second child about three months after Ya’ana’s return. But the newborn was just eight months old when the Nigerian Army came for the old woman again.

Fanna’s father passed away over the years, while his wife was away. She has since remarried. But—as they would later learn—missing Muktar, who should be 27 years old now, had joined Boko Haram and is somewhere in Sambisa forest waging the terror group’s war. A family friend is convinced his mother’s wrongful detention was a major factor. It has been over six years now and they have not heard from him.

…

Today, Bulabulin Ngarannam is relatively peaceful and Ya’ana continues to sell food and cold drinks to residents. Even as she narrates her experience, she takes frequent breaks to attend to customers. But Boko Haram is threatening a comeback to Maiduguri that may open a new chapter of violence.

Last February, the Abubakar-Shekau-led faction breached a section of the trench protecting the Borno state capital and fired mortars that killed at least 15 people across the city. Perhaps even more threatening is the breakaway Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP) which has recently cast the city into darkness by habitually attacking electricity towers and is plotting a blockade to make life unbearable for locals.

For Ya’ana, however, this is just one of several concerns.

Because she mediated between quarrelling women during her first detention, she was tied to a grinding machine and a military officer hit her repeatedly with his boots. Her sight has been imperfect since this incident and, time and again, she feels piercing pain dashing through her eyes. Naturally, she fears armed men of the Nigerian military may march to her house at any time and have her arrested under the flimsiest pretext—for the third time.

“I don’t allow anyone to my house after 10 p.m. in the evening,” she declares.

*Names have been changed to protect their identities.

This investigative report is a partnership between the African Transitional Justice Legacy Fund and HumAngle Media under the ‘Mediating Transitional Justice Efforts in North-East’ project.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter